When he cross-examined the Merlin Operation manager Bob S at Jeffrey Sterling’s trial, defense attorney Barry Pollock asked whether Bob S thought he was doing 70% of the thinking on the operation. When Bob S denied that, Pollock reminded Bob S of his February 28, 2006 FBI testimony, where he had said he was doing 70% of the thinking to Sterling’s 30%. “This was shortly after publication of book that revealed the whole operation,” Bob S explained his earlier comment. “I was being ungenerous.”

Similarly, when he cross-examined Merlin himself, defense attorney Edward MacMahon asked whether he had told the FBI in March 2006 that Sterling (whom elsewhere Merlin called “lazy” and “irresponsible” while denying earlier statements he had made about Sterling’s race) was just a middleman between Merlin and Bob S who helped prepare the letters Merlin would send out to Iran.

MacMahon: You, you told the FBI that Sterling merely acted as a middleman — and this is in 2006 — as a middleman between you and Bob to prepare letters to be included in the package of technical documents, right?

Merlin: Some kind of, yes?

MacMahon: So the person that was making the final say as to what went in any letter you sent as far as you knew was Bob, right?

Merlin: I, I don’t know what is hierarchical.

I raise these comments — both apparently made only after the publication of Risen’s book — because of some oddities in the CIA cables documenting the operation.

Bob S’ 70%

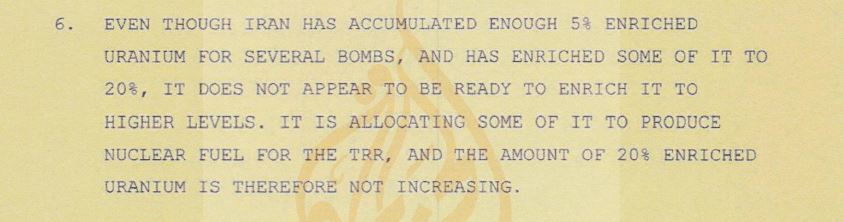

To some degree, the cables that cover the period when Sterling handled Merlin do make it clear the degree to which Bob S was running this operation, and Sterling was just holding Merlin’s hand as he tried to reach out to Iranians.

Over the period in question (the first meeting when Sterling met alone with Merlin was January 12, 1999; he handed over Merlin to Stephen Y on May 24, 2000 (though it appears Bob S had already excluded Sterling from at least one meeting, as noted below), most of the cables written by Sterling deal with the tedium of Merlin’s pay and include — always verbatim — Merlin’s correspondence with the Iranians. Sterling’s cables often ask for input from Langley on Merlin’s drafts; he expresses some concern about the lag during spring 1999 when CIA was getting export control approval for the program.

Then, in the May 13, 1999 cable (Exhibit 24), as Merlin seems to be getting more interest from Iranian Institution 4 (in spite of his having sent his resume and business proposition letter separately), Sterling notes that Bob S will need to inform Merlin where the program heads from here. “[M] should expect a visit from Mr. S who will provide an update on the definite direction of the project. [M] understands that there are aspects of the project that require certain approvals beyond the purview of C/O.”

The next cable (Exhibit 25) describes the May 25, 1999 meeting at which Bob S, with Sterling in attendance, told Merlin that the target of this operation would be Iranian Subject 1. This plan actually dated back to December 18, 1998 (Exhibit 16). In that cable, Bob S referenced a November 20, 1998 cable (not included as an exhibit nor apparently turned over to FBI as evidence) that apparently described IS1’s “new public position” for which he would be “arriving in Vienna in Mid-December to assume his new duties” (one of Bob S’ later cables would identify IS1 as the Mission Manager in Vienna). But it wasn’t until May of the following year when Bob S (and not Sterling) instructed Merlin that he should start finding ways to reach out to IS1. Note, one paragraph of that cable — following on a discussion of IS1 — is redacted.

At the next meeting — on June 17, 1999 (Exhibit 27) — Merlin told Sterling that he was having problems locating IS1, though some of this discussion is redacted.

Then, in spite of the indication that Sterling had tentatively scheduled a meeting for July 5, 1999, we see no further meeting reports until November 5, 1999. (Though on July 23, 1999, someone applied for reauthorization to use Merlin as an asset; Exhibit 29.) It appears that only one cable from this period, which would have been numbered C2975-2976, was turned over during the investigation but not entered into evidence, if the Bates numbers on the cables are any indication. Given the report in the 11/5/1999 cable that Merlin had gone AWOL, it’s likely things were already going south between him and Sterling. From that period forward, Bob S either soloed or attended most meetings with Sterling and Merlin, with one very notable exception.

The exception was the January 10, 2000 meeting (Exhibit 35) at which Sterling informed Merlin CIA would withhold money Merlin believed — rightly, it appears — he was owed. Given that Sterling had already (on November 18, 1999) unsuccessfully requested a transfer out of NY, where he believed he was being harassed for his race, it’s hard not to wonder whether they deliberately sent Sterling out to deliver the bad news, anticipating they’d soon be giving Merlin a new case officer within short order anyway.

All of that is to say that, in spite of the several ways that Sterling appears to have managed Merlin with more professionalism than his prior case officer and arguably even than Bob S, Bob S was running the show, which includes making key decisions and at key moments, dictating how the reporting on the operation appeared.

Two versions of November 18, 1999

To see how this manifested, it’s worth comparing the two cables recording (in part or in whole) the November 18, 1999 meeting between Bob S, Sterling, and Merlin.

The first version (Exhibit 31), written on November 24 by Bob S from Langley and addressed to NY and Vienna — Office #5 — for information, appears under the heading “Iranian Subject 1 is in Vienna” and references a cable from Vienna (this cable, too, appears not to have been turned over as evidence). As such, the cable describes the results of the meeting with Merlin in context of the arrival of IS1 in Vienna, using the “good news” offered by Merlin as an opportunity to flesh out the plan for the blueprint hand off in Vienna. Presumably, paragraph 2 of the cable (which is redacted) lays out the news on IS1’s presence in Vienna. Bob S then presents all the good news involving Merlin in that context with a flourish.

During an 18 November Meeting with [M] Officer [Jeffrey Sterling] and HQS CPD Officer [Mr. S.], [M] provided two pieces of good news. The first was that he has obtained a new [Country A] passport (which he showed C/O’s) and will soon apply for an Austrian visa. His possession of a Green Card should facilitate the issuance of the latter. The second and more significant development was an e-mail dated 7 November which [M] had received from [Iranian Institution 1] Professor [Iranian Subject 2 IS2). [IS2] said he had been going through old e-mailsl and found a 1998 message from [M]. He asked [M] to respond and provide more information about himself. [M] did so in a generic fashion. This contact from [IS2] provides an excellent opportunity to ease [M]’s (and his disinformation packet’s) way in to [Iranian Subject 1 (IS1)] who until recently was also [at Iranian Institution 1] and is still featured on its website.

He then goes on to lay out what he presents as a plan crafted with the help of folks at HQ and Sterling (remember, this was written from Langley, not NY). That plan includes recognition that Merlin is “no one’s idea of a clandestine operative;” to compensate for that, Bob S envisions (resources willing) a Sterling trip to Vienna so he can help provide clear instructions to Merlin as well as Mrs. Merlin traveling to Vienna with the scientist because she was instrumental in his cooperation with the CIA in the first place and is a calming influence.

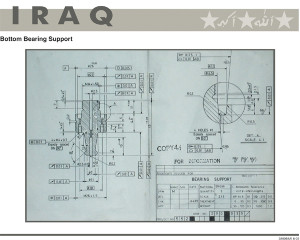

4) Shortly before he prepares to launch in Vienna (see below RE timing and mechanics) we will have [M] advise [IS2] via e-mail that he is going on vacation in Vienna with his wife and will stop by the Iranian IAEA Mission there with a packet of interesting information for [IS2], asking IS2 to alert the mission to expect [M]. When he shows up at the mission, [M] will have the packet containing the [CP1] disinformation in an envelope addressed to [IS2] and will ask to see [IS1] to make sure the package gets delivered to the right man. [IS1] is likely to acknowledge that he too is from [Iranian Institution 1] and that he knows [IS2]. This will let [M] plant his story (of repeated efforts to find a receptive audience in Iran) more firmly and give the Iranians a chance to see that [M] is indeed a Russian and a nuclear weapons veteran. Even if [IS1] does not see [M] presenting a package with a known addressee at a prestigious Iranian [redacted] institution can only help advance our plan to have the information taken seriously.

5) Per discussion at HQS and with [Sterling], we believe it best to send [M] to Vienna with his wife in early January (after the Austrian Christmas pause and the Islamic holiday of Ramadan, which begins on 9 December and ends on 8 January) to make the approach to [IS1]. His wife, [Mrs M], was instrumental in getting him to cooperate with [CIA] in the first place and is a definite calming influence on him. [M] is no one’s idea of a clandestine operative and we believe it wiser to refrain from meeting him while he is in Vienna. That said, he needs to be thoroughly prepared. One option – contingent on available resources – would be for [Mr S] and [Sterling to] visit Vienna during the first week of the New Year [redacted] so he can given the rather differently-oriented [M] as much concrete detail about where he has to go and what he has to do as possible. [1 line redacted]

Spoiler alert: while Mrs. Merlin did travel to Vienna with her husband (and probably had a big role in even getting him to go and — my suspicion is — had a role in the operational security measures Merlin took which helped doom the operation, though neither she nor the CIA would ever admit that), Sterling never did make the trip, and Bob S’ instructions — which Bob S’ habit of flourish aside were probably also deficient because he was too familiar with the city — ended up being one of the problems with the trip. It’s worth mentioning, too, that according to Bob S’ testimony, he made several trips to case out Iran’s IAEA mission in the months leading up to the operation and one of his cables describes having done so too.

Now compare Bob S’ cable with Sterling’s (Exhibit 31), written on December 1, 1999, a week after Bob S’ cable and 12 days after the actual meeting (it’s probably worth noting that on the very same day this meeting took place, Sterling asked for a transfer out of CIA’s New York office, and within 5 days his boss was scolding him for having done so), and addressed to Langley and — like Bob S’ cable — Vienna, for information.

Sterling saves his enthusiasm over the outreach to Merlin from IS2 for his last paragraph.

Feel this is a fortuitous turn of events for the operation, as a preliminary thought, the contact from [IS2] can be exploited to either provide another person to present the material to, or somehow utilize this contact to provide a more definite entree to [IS1] for [M].

Curiously, that paragraph seemed to show little awareness of Bob S’ extensive plans for how to exploit the IS2 contact to provide “a more definite entree to IS1,” even though Sterling references the cable Bob S wrote.

Aside from the first, action, paragraph in Sterling’s cable (which is redacted), the sole apparent explanation for why he wrote a cable after Bob S had already written one reporting all the same news from the meeting as Sterling would seems to be the inclusion of the verbatim content of the outreach from IS2.

During the meeting, [M] mentioned that he had received the following email from [Iranian Subject 2 (IS2)] from [Iranian Institution 1] dated 7 Nov:

Dear [M]

I was reviewing my old mails. I found you last year email. I want to know more about you. Could you let me have more information regarding your work, your hobby, your interest, etc?

Regards,

[Iranian Subject 2]

[IS2]’s email address is [redacted]

It’s not surprising Sterling included the verbatim email — he always did that in cables he wrote solo. It’s just rather curious that Sterling submitted his “preliminary thoughts” — along with the verbatim language — so long after Bob S had rolled out his plan.

Prelude to a clusterfuck

The next cable (Exhibit 33), dated December 16, 1999 and describing the December 14 meeting between Sterling, Merlin, and Bob S, reflects continued uncertainty about how to get Merlin to Vienna in such a way that he didn’t screw up the operation. “[M] has and will be provided with enough information so that any concerns he will have about finding the building should be alleviated,” the cable optimistically predicted. At that point, however, it wasn’t getting lost that had Merlin worried. It was that his wife would find out what he had been up to (though she almost certainly already knew).

When asked, [M] expressed as his main concern actually carrying the documents on his person when he travels to Vienna. [M]’s preference is that his wife ([Mrs. M]) not know any specifics about his work for the CIA. He feels certain that she will discover the package and have many questions that he would prefer not to have to answer.

Note that the action paragraph of this cable is redacted.

Read more →