Update, 2/21/20: This post has been updated reflecting the DOJ response to Schulte’s bid for a mistrial based on this dispute. The response makes quite clear that the administrative leave pertains only to concerns about Michael’s candor regarding Schulte’s behavior.

Neither the Government nor the CIA believes anyone else was involved, and the defendant’s claims otherwise are based on a distorted reading of the CIA memorandum placing Michael on administrative leave (the “CIA Memorandum”). The CIA Memorandum explicitly states that Michael was placed on leave because of concerns he was not providing information about the defendant (not that he is a suspect in the theft); the Government has confirmed with the author of that memorandum that the memorandum was not intended to suggest that it was Michael rather than the defendant who stole the Vault 7 Information; and, in any event, the defendant has had all of the relevant information underlying the CIA Memorandum for months in advance of trial.

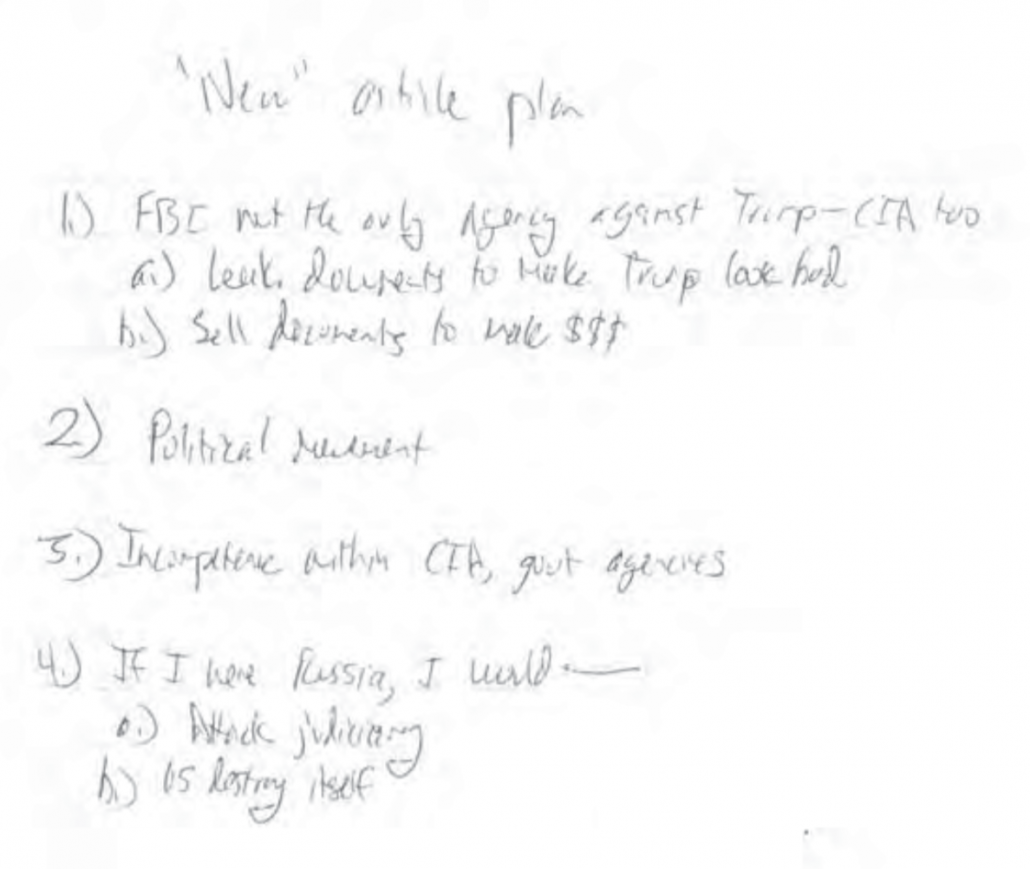

There was some drama at the end of last week’s testimony in the trial of accused Vault 7 leaker, Joshua Schulte. Schulte’s lawyers forced the government to admit that Schulte’s buddy, testifying under the name, “Michael,” is on paid leave from the CIA for lack of candor.

It turns out “Michael” got put on paid leave in August 2019, shortly after his seventh interview as part of the investigation (his interview dates, based DOJ’s response off Shroff’s cross-examination, were March 16, 2017, June 1, 2017, June 2, 2017, June 6, 2017, August 30, 2017, March 8, 2018, August 16, 2019, and January 13, 2020).

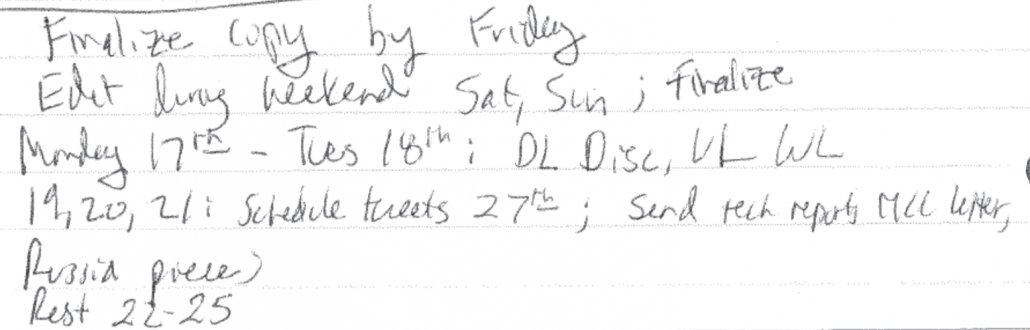

While prosecutors provided Schulte the underlying interview reports (the last one wasn’t even a 302 because prosecutors led the interview, with just one FBI agent present, possibly as part of pre-trial prep), they withheld documents explaining the personnel change until providing part of the documentation the night before Michael’s testimony starting on February 12. Technically, that late notice probably complied with Jencks, but once Judge Paul Crotty realized what documentation had been shared with whom, he granted the defense request for a continuance of Michael’s testimony so they could better understand the implications. Withholding the information was a dickish move on the part of the prosecutors.

The question is, why prosecutors did this, why they withheld information that might be deemed key to a fair trial.

I don’t think defense counsel Sabrina Shroff’s seeming take — that the government tried to hide Michael’s personnel status to hide that they were (purportedly) coercing him to get his story “to morph a little,” to testify in the way he had on threat of false statements charges and certain firing from the CIA — makes sense. That’s because, on the two key issues he testified about, Michael testified in roughly the same way in court as he did in FBI interviews in the wake of the Vault 7 disclosure.

On the stand under direct examination, Michael explained how he told his and Schulte’s colleague, Jeremy Weber, to take away Schulte’s access because he feared Schulte would respond to losing access to his own projects by restoring that access, which would lead to significant trouble.

Q. Did you ever speak with Mr. Weber about the defendant’s anger?

A. Yes.

Q. What did you talk about?

A. We didn’t talk about his anger per se. But, I told Jeremy that he should remove all of Josh’s admin accesses.

Q. Why did you ask Mr. Weber to do that?

A. I felt like Jeremy was kind of, like, setting him up. I knew that Josh was mad at Jeremy, and that he was putting him in a position where Josh had the ability or the access to change permissions on the project in question. And that he would do that because he didn’t respect Jeremy’s authority.

As Shroff elicited on cross-examination, Michael told the FBI something very similar on August 30, 2017.

Q. And it is in this meeting, if you remember, that you told the FBI that, in your opinion, Mr. Weber was setting Mr. Schulte up. Do you remember that?

A. I remember feeling that way.

Q. Okay. By that you mean that you thought Mr. Weber was setting Mr. Schulte up to fail at his job at the CIA, right?

A. I thought he was — baiting him into using his accesses, for a lack of a better word.

[snip]

A. Yeah, I thought he was setting — he was creating circumstances where he knew that Josh had access to change permissions on the server, Josh was an admin. He was telling Josh you cannot do this. But Josh technically could do that, right, he had the technical capability to do that. So, Josh was going to do that.

Q. Okay. You told Mr. Weber your concern?

A. Yes.

Q. And Mr. Weber said butt out, correct?

A. Yes, in summary. Mr. Weber said butt out.

Likewise, last week the government got Michael to explain how, on April 20, 2016 (the day the government alleges Schulte stole the Vault 7 files) Schulte first invited Michael to work out at the gym as they normally would, but then didn’t respond for an hour, at which point Michael witnessed — and took a screen cap of — Schulte deleting log files, which means Schulte’s buddy documented in real time as his buddy stole the files.

Q. It is a little difficult, so let’s blow up the left side of the screen. Do you recognize what we’re looking at?

A. Yes.

Q. How do you recognize it?

A. It is a screenshot I took.

Q. What is it a screenshot of?

A. It a screenshot of, in the bottom you can see a VM being reverted and then a snapshot removed.

Q. It is a screenshot of a computer screen?

A. Yes, of my computer screen.

Q. What date and time did you take this screenshot?

A. The date was April 20, and time was 6:56 p.m.

Q. What year was that?

A. 2016.

Michael explained his past testimony to the FBI to Shroff using much the same story (though she used a different screen cap that may be of import).

Q. Uh-huh.

A. I believe I was trying to dig into what the screenshot meant. I was unsure. You know, I took the screenshot because I was concerned, and then I tried to validate those concerns by determining did a person do these reverts, or was this a system action? This is me trying to dig into that. I have debug view open to see if there was any debug messages about reverting the VMs or something. That could have been there already. I don’t know. But specifically this command prompt here that you see, this black-and-white text, the command prompt, I was looking at IP addresses.

Q. And did you do that on the same day, or you did this later?

[snip]

Q. And you don’t see anything before the start time of 6:55?

A. Yeah. I don’t see anything before 6:55 — or I see 6:51.

Q. Right, but you’re saying that even though your vSphere was running, you didn’t see any April 16 snapshot?

A. Yeah. I don’t see an April 16 snapshot.

On redirect prosecutors will have Michael make it clear that the reason he didn’t see an April 16 snapshot is because it had been deleted, making this a damning admission, not a helpful one.

So knowing that the CIA has concerns that Michael isn’t telling the truth about all this doesn’t help Shroff rebut the most damning details of Michael’s testimony: that one of Schulte’s closest friends at CIA tried to intervene to prevent Schulte from doing something stupid before it happened, and the same friend happened to get online and capture proof of it happening in real time.

Nor does it help her rebut another damning detail from Michael’s testimony, a description of how a rubber band fight between him and Schulte led to Michael hitting Schulte physically.

Q. Could you just describe generally what happened.

A. Sure. On that day, Josh hit me with a rubber band, I hit him back with a rubber band. This went back and forth until late at night. I hit him with a rubber band and then ran away before he could hit me back. He trashed my desk. I trashed his desk. And then I was backed up against Jeremy’s desk and Josh was looking at me, kind of coming towards me. And something came over me and I just hit him.

This might seem, if you’re the NYT trying to cull the trial record for glimpses of the banality of CIA cubicle life, like an innocuous detail. But it’s not. Schulte’s defense, such as he has offered one so far, is that he had a real gripe with a colleague, Amol, which escalated into both being moved, him losing his SysAdmin access, which led to his retaliation against the CIA. But what Amol did was take Schulte’s Nerf darts away when they landed on his desk and make verbal — but never physical — attacks against Schulte. Yet Schulte obtained a restraining order against Amol, not against Michael, the guy who really had physically hit him. This rubber band fight with Michael, as juvenile as it seems, actually undermines Schulte’s claim that his complaint against Amol made sense.

Meanwhile, Shroff herself seems to have brought out the detail that led to CIA’s personnel action (and which Judge Crotty argued prosecutors had withheld by not sharing the full CIA notice). On direct, Michael told prosecutor Sidhardha Kamaraju that he stopped digging to find out what had happened because he remembered that he was using a regular user account that — he couldn’t remember — might not have the right permissions to view logs.

Q. Did that seem strange to you that there were no log files there?

A. Yes. At first this was strange to me.

Q. Why did you think it was strange at first?

A. Just because, a system managing this many VMs should have lots of logs.

Q. Did you try to find out why there weren’t any log files there?

A. I did some more digging, yes.

Q. What did you think as a result of your digging?

A. I remembered that this account that I was using was a regular user account, and I couldn’t remember if the regular user accounts had administrative permissions to view logs.

But as Shroff had him explain on cross, Michael told the FBI that Schulte had given him “pseudo creds” to one of his virtual machines. He told them that almost three months before the FBI first asked him about the screen cap showing Schulte delete logs.

Q. No, it’s not correct? What is it then?

A. This is a VM that he would have run on his DevLAN machine.

Q. So it is a virtual machine that he ran on his own DevLAN, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Okay. So it says “Josh.” Correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Then it says “Michael,” correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And then it says “other,” correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And they asked you about this document, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And you told them, did you not, that Josh had given you what you turned as a phrase “pseudo creds,” correct?

A. I don’t remember specific wording but, yes. I believe he gave me pseudo accesses to this VM.

[snip]

Q. And then you told them that you probably had root access to the machine to do with it what you wanted, correct?

A. Yes. If I had pseudo creds, then that’s true.

Q. They asked you if you were surprised to find out that you shared a VM with Josh, and you said no, correct?

This is a reference to “sudo” credentials, which is root access. The government response makes it clear that Michael had administrative access, using the “root” password, to the ESXi server, but did not have admin access to the Atlassian suite, which is what Schulte alleged used to steal the documents.

Michael’s “system administrator” privileges were well-documented in the reports of the FBI interviews. Indeed, Michael’s “system administrator privileges” were discussed in at least three different interviews, one of Michael and the other two of Mr. Weber:

- In a March 22, 2017 interview, Weber stated that “Michael, [the defendant], [Weber], and [Matt] had administrative access to the ESXi server …. A root password was required to directly log into the ESXi server and this password was shared on OSB’s Confluence page that all of OSB had access to.” CLASSIFIED JAS _ 001318 – 001320 ( emphasis added).

- In a May 26, 2017 interview, Weber stated that he “believed that [Matt] and [Michael] were possibly added as [ESXi] administrators later.” CLASSIFIED JAS 010153 – 010159.

- In a March 8, 2018 interview, Michael explained the relevant distinction in administrative privileges: “There is a difference between being considered an Atlassian administrator and having the root password for the ESXi server. The root password for the ESXi server was likely needed to create and control VMs, which are frequently used by developers for testing. [Michael] believed he used the ESXi root password to create VMs. The status of being an Atlassian administrator is reflected in the user’s domain credentials. [Michael] is not aware of how to get access to Atlassian as an administrator.” CLASSIFIED JAS _ O I 0514 ( emphasis added).

These reports make clear that Michael never had Atlassian administrator privileges, and thus did not have the ability to access or copy the Altabackups (from which the Vault 7 Information was stolen).

Still, that part of his testimony hasn’t changed. And CIA would have known about all this by August 2017, two years before they put Michael on administrative leave.

And curiously, having had this information for quite some time, Schulte never tried to suggest that Michael could have conducted the theft while using Schulte’s credentials.

Thus far, it looks like the CIA moved Michael to administrative leave not to change his pre-August 2019 testimony — because that hasn’t changed — but out of concern that Michael learned about Schulte’s actions in real time but didn’t tell anyone, not in 2016 when the CIA could have done something about it, nor immediately after the Vault 7 publication. It wasn’t until the FBI discovered the screen cap and asked Michael about it in August 2017 that he told this story.

Q. Is it fair to say, sir, by the time the FBI showed it to you, you had forgotten about the screenshot?

A. Yes.

Q. You had taken it on April 20, 2016, right?

A. Yes.

Michael similarly did not offer up to the FBI that Schulte contacted him after the first Vault 7 publication (presumably in March) until it came up in June 2017.

Q. It was during this meeting that you told them about Mr. Schulte reaching out to you after the leaks had become public; correct? Do you remember that?

A. I remember telling them about him reaching out to me. I don’t remember if it was this specific meeting.

Q. Okay. Take a look at the highlighted portion on page one, okay?

A. Okay.

Q. You told the FBI, did you not, that Mr. Schulte had sounded upset to you that people thought it was he who had done the leaks, correct?

A. Yes. I believe the word was he seemed concerned.

Q. Right. You would be concerned too if somebody accused you of something you didn’t do, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And you also told them that you essentially blew him off, correct? You didn’t want to engage and talk to him, correct?

A. Yes, I ignored the initial text messages. And then in the phone call, I didn’t want to talk about that subject.

Q. Okay. And at first you didn’t report the fact that Mr. Schulte contacted you, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. And then somehow or the other, the deputy chief of EDG said if somebody’s contacted you, report it. And then you reported it, correct?

A. Correct.

The most likely explanation for CIA’s change in Michael’s personnel status, then (but not the timing), is that Michael did not alert security when he had the opportunity, and then when he discovered that his buddy was the lead suspect for a huge theft of CIA tools, he tried to downplay his knowledge, perhaps hoping to avoid suspicion himself (which, if true, backfired). As Michael said himself in one of his FBI interviews, it sucks when you’re the single guy the prime suspect for a crime has given credentials to his VM, by name.

Q. And then you kind of added that it kind of sucked that your name was on this VM, correct?

A. I don’t remember that.

Q. Take a look at the first paragraph, page two of eight. It sucks. I don’t mean to be rude, but that’s the word it says, “suck,” right?

A. Yes.

Q. That your name was on the virtual machine, correct?

A. Correct.

Q. And that you understood from the FBI that that put you under the microscope, correct?

A. Correct.

So, again, the most likely implication of all this is just that the CIA believes Michael had information about a data breach in real time that he offered unconvincing (and, possibly, technically false) explanations for why he didn’t alert anyone.

But, particularly given the delay in putting him on administrative leave, I wonder whether there’s not something more.

DOJ and CIA clearly suspect Michael is being less than forthcoming about what he witnessed in real time. That doesn’t undermine his value as a witness to having taken the screen shot, but it does raise questions about his trustworthiness to retain clearance at CIA. It does undermine his claims to the FBI, which Shroff portrayed as largely unique among CIA witnesses, that Schulte wasn’t the culprit (which he hasn’t yet explained in the presence of the jury).

That may, however, raise questions about his candor on other answers asked by the FBI, answers that may speak to how Schulte came to steal CIA’s hacking tools in the first place or even whether Michael knew more about it than he knows.

For example, the FBI asked Michael repeatedly about Schulte’s League of Legends habit.

Q. He played a lot of League of Legends or something?

A. Yes.

Q. Some kind of game?

A. Yes, it’s a video game.

Q. A lot of men, people play it; is that right?

A. It has a large user base.

Q. It is some kind of online game where you pretend to have avatars and kill each other online or something like that? Is that right, basically?

A. Yes.

Q. And you played that game, did you not, with Mr. Schulte? A. Yes.

In recent years the government has come to regard gaming communications systems as a means to communicate covertly (which Schulte would have known because his hacking tools targeted terrorists).

They also asked Michael whether Schulte was a “vigilante hacker” by night, and about his Tor usage (which, according to Michael, Schulte didn’t hide).

Q. You remember the FBI asking you if Mr. Schulte was a vigilante hacker by night? Do you remember that phrase they used?

A. I think I do actually, yes.

Q. You told them, no, you didn’t know him to be a vigilante hacker at night?

A. Correct.

Q. You in fact did not know him to be a vigilante hacker at night.

A. Correct. I did not know him to be a vigilante hacker.

This question is particularly relevant given Schulte’s claim, in communicating with a journalist from jail, that he had been involved with Anonymous.

The FBI asked Michael how he came to buy two hard drives for Schulte from Amazon, the same place Schulte bought a SATA adapter they think he used in the theft.

A. I only ever bought him hard drives this one time. But the reason, like, I wouldn’t normally just buy him hard drives, I would have told him to buy it himself. But the reason was there was some deal going on, and so he’s like, if I buy it and then you buy it, we all get the deal and I’ll just pay you back.

Q. Right. It’s normal, right?

A. Yeah.

Q. Yeah. Amazon had a cap on the sale, like everyone could only get two, and he wanted four or something like that?

A. Yes, it was something along those lines.

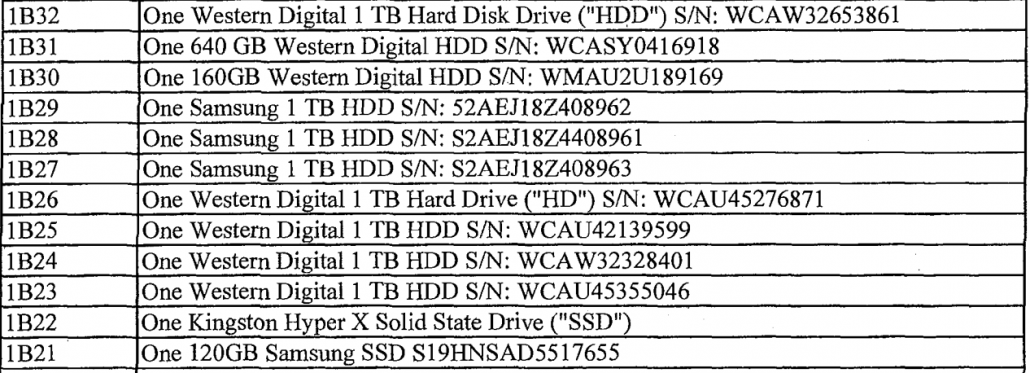

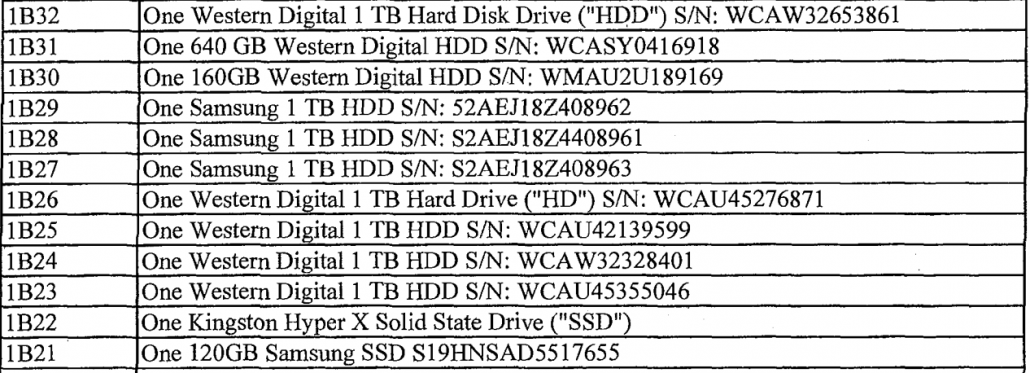

Of the hard drives the FBI seized from Schulte’s home in March 2017 (PDF 116), the ones he owned the most copies of — the 1TB Western Digital drives — are the ones they suspect were used in the theft because they were overwritten.

The FBI asked about a time when Michael worked over a weekend, when Schulte also happened to be working. Michael first explained he had been working on his performance review, but when he subsequently checked his records, discovered that couldn’t be right. Even though he recognized how unusual it was for him to be working the same weekend as Schulte without knowing Schulte was there, he concluded (like he had about the deleted log files) that it was normal.

Q. They asked you about that weekend because Mr. Schulte also happened to be working that weekend?

A. They mentioned that, yes.

Q. Did you think it was odd that Mr. Schulte was working that weekend or did the FBI think it was odd that Mr. Schulte was working that weekend or both?

A. At first I thought it was odd.

Q. Okay.

A. Just because —

Q. Go ahead.

A. Just because, you know, although it was normal to come in on the weekend, it was less common — rare, I would say, to come in on the weekend. One of us probably would have told each other, you know, we were going to come in on the weekend. But then I looked at my situation, I was like, well, I didn’t tell him I was coming in, so I guess this is normal.

The government may still be trying to figure out precisely when Schulte removed the files on hard drives from CIA — they also asked Michael about that repeatedly — which is why these questions are so important. Among the reasons CIA put him on leave, per the government response, is that he and Schulte left together that night; if Schulte had carried out hard drives that night Michael may have seen them.

The FBI asked about Michael’s role — apparently unplanned — in helping Schulte move to New York.

Q. Then they talked to you about your involvement in helping him move from Virginia to New York, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. They asked you a whole series of questions as to how you came about to help him move, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And they asked you why you helped him move, correct?

A. I don’t remember specific questions, but I do remember questions about helping him move.

Q. And you explained to them that it was like a coincidence, right? You’d already planned a trip with another friend, he was moving at the same time, he needed help loading up luggage and moving stuff, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. It was not preplanned, right? It just happened, right?

A. Yeah.

Q. You told them that you had already planned to do this with another friend, right?

A. Yes.

Q. And then they asked you about that friend, correct? They asked you what the name of the friend was, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Then they asked you for your friend’s number, correct?

A. I don’t remember specifically what information they asked for.

The FBI also asked Michael about the stuff he left with him when he moved to New York, which Michael explained was just furniture, though a lot of it.

Q. We’ll come back to that if we need to. Let’s move to the next point. They then asked you if Mr. Schulte had left any stuff with you, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. You told them that he had, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. It was normal, everyday stuff he left with you, correct?

A. I wouldn’t say it’s normal. It was a lot of furniture. So I don’t think that’s normal.

Again, it may well be that, two years after the FBI would have had real questions about Michael’s candor, the CIA concluded they had to reconsider his employment because he could have prevented the theft but did not.

But I wonder whether, by the time DOJ posed these questions anew in August 2019 (which, if I’ve got his interview dates correct, was the only interview he had after the time that Schulte had been formally charged with the theft), their doubts about his other answers had taken on greater significance.

Update: Clarified that the “pseudo” credentials in the transcript are a reference to “sudo” root access.

Update: In a letter opposing any order to share the CIA’s determination to put Michael on paid leave, the government explains the basis for it:

- Adverse polygraph results

- His relationship with Schulte

- His close proximity to the theft of the data and (what appears to be) reason to believe he witnessed more anomalies at the time Schulte was stealing it

- “Recent inquiries” suggesting Michael may still be hiding information about the theft

- His “unwillingness to cooperate with a CIA security investigation into his physical altercation with the defendant”

That is, the speculation above seems to be born out. The three questions that leaves are”

- Why did they put him on leave rather than fire him?

- Which of the questions above do they think he was not truthful about?

- Why did they wait until August 2019 to put him on leave?