18 USC 793e in the Time of Shadow Brokers and Donald Trump

Late last year, a Foreign Affairs article by former Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence Sue Gordon and former DOD Chief of Staff Eric Rosenbach asserted that the files leaked in 2016 and 2017 by Shadow Brokers came from two NSA officers who brought the files home from work.

In two separate incidents, employees of an NSA unit that was then known as the Office of Tailored Access Operations—an outfit that conducts the agency’s most sensitive cybersurveillance operations—removed extremely powerful tools from top-secret NSA networks and, incredibly, took them home. Eventually, the Shadow Brokers—a mysterious hacking group with ties to Russian intelligence services—got their hands on some of the NSA tools and released them on the Internet. As one former TAO employee told The Washington Post, these were “the keys to the kingdom”—digital tools that would “undermine the security of a lot of major government and corporate networks both here and abroad.”

One such tool, known as “EternalBlue,” got into the wrong hands and has been used to unleash a scourge of ransomware attacks—in which hackers paralyze computer systems until their demands are met—that will plague the world for years to come. Two of the most destructive cyberattacks in history made use of tools that were based on EternalBlue: the so-called WannaCry attack, launched by North Korea in 2017, which caused major disruptions at the British National Health Service for at least a week, and the NotPetya attack, carried out that same year by Russian-backed operatives, which resulted in more than $10 billion in damage to the global economy and caused weeks of delays at the world’s largest shipping company, Maersk. [my emphasis]

That statement certainly doesn’t amount to official confirmation that that’s where the files came from (and I’ve been told that the scope of the files released by Shadow Brokers would have required at least one more source). But the piece is as close as anyone with direct knowledge of the matter — as Gordon would have had from the aftermath — has come to confirming on the record what several strands of reporting had laid out in 2016 and 2017: that the NSA files that were leaked and then redeployed in two devastating global cyberattacks came from two guys who brought highly classified files home from the NSA.

The two men in question, Nghia Pho and Hal Martin, were prosecuted under 18 USC 793e, likely the same part of the Espionage Act under which the former President is being investigated. Pho (who was prosecuted by Thomas Windom, one of the prosecutors currently leading the fake elector investigation) pled guilty in 2017 and was sentenced to 66 months in prison; he is processing through re-entry for release next month. Martin pled guilty in 2019 and was sentenced to 108 months in prison.

The government never formally claimed that either man caused hostile powers to obtain these files, much less voluntarily gave them to foreign actors. Yet it used 793e to hold them accountable for the damage their negligence caused.

There has never been any explanation of how the files from Martin would have gotten to the still unidentified entity that released them.

But there is part of an explanation how files from Pho got stolen. WSJ reported in 2017 that the Kaspersky Anti-Virus software Pho was running on his home computer led the Russian security firm to discover that Pho had the NSA’s hacking tools on the machine. Somehow (the implication is that Kaspersky alerted the Russian government) that discovery led Russian hackers to subsequently target Pho’s computer and steal the files. In response to the WSJ report, Kaspersky issued their own report (here’s a summary from Kim Zetter). It acknowledged that Kaspersky AV had pulled in NSA tools after triggering on a known indicator of NSA compromise (the report claimed, and you can choose to believe that or not, that Kaspersky had deleted the most interesting parts of the files obtained). But it also revealed that in that same period, Pho had briefly disabled his Kaspersky AV and downloaded a pirated copy of Microsoft Office, which led to at least one backdoor being loaded onto his computer via which hostile actors would have been able to steal the NSA’s crown jewels.

Whichever version of the story you believe, both confirm that Kaspersky AV provided a way to identify a computer storing known NSA hacking tools, which then led Pho — someone of sufficient seniority to be profiled by foreign intelligence services — to be targeted for compromise. Pho didn’t have to give the files he brought home from work to Russia and other malicious foreign entities. Merely by loading them onto his inadequately protected computer and doing a couple of other irresponsible things, he made the files available to be stolen and then used in one of the most devastating information operations in history. Pho’s own inconsistent motives didn’t matter; what mattered was that actions he took made it easy for malicious actors to pull off the kind of spying coup that normally takes recruiting a high-placed spy like Robert Hanssen or Aldrich Ames.

In the aftermath of the Shadow Brokers investigation, the government’s counterintelligence investigators may have begun to place more weight on the gravity of merely bringing home sensitive files, independent of any decision to share them with journalists or spies.

Consider the case of Terry Albury, the FBI Agent who shared a number of files on the FBI’s targeting of Muslims with The Intercept. As part of a plea agreement, the government charged Albury with two counts of 793e, one for a document about FBI informants that was ultimately published by The Intercept, and another (about an online terrorist recruiting platform) that Albury merely brought home. The government’s sentencing memo described the import of files he brought home but did not share with The Intercept this way:

The charged retention document relates to the online recruitment efforts of a terrorist organization. The defense asserts that Albury photographed materials “to the extent they impacted domestic counter-terrorism policy.” (Defense Pos. at 37). This, however, ignores the fact that he also took documents relating to global counterintelligence threats and force protection, as well as many documents that implicated particularly sensitive Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act collection. The retention of these materials is particularly egregious because Albury’s pattern of behavior indicates that had the FBI not disrupted Albury and the threat he posed to our country’s safety and national security, his actions would have placed those materials in the public domain for consumption by anyone, foreign or domestic.

And in a declaration accompanying Albury’s sentencing, Bill Priestap raised the concern that by loading some of the files onto an Internet-accessible computer, Albury could have made them available to entities he had no intention of sharing them with.

The defendant had placed certain of these materials on a personal computing device that connects to the Internet, which creates additional concerns that the information has been or will be transmitted or acquired by individuals or groups not entitled to receive it.

This is the scenario that, one year earlier, was publicly offered as an explanation for the theft of the files behind The Shadow Brokers; someone brought sensitive files home and, without intending to, made them potentially available to foreign hackers or spies.

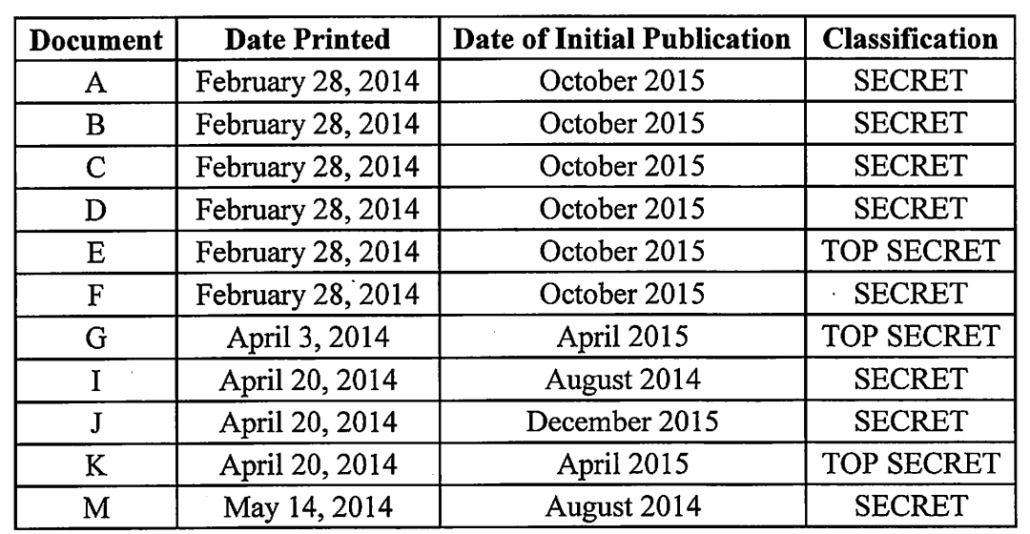

Albury was sentenced to four years in prison for bringing home 58 documents, of which 35 were classified Secret, and sending 25 documents, of which 16 were classified Secret, to the Intercept.

Then there’s the case of Daniel Hale, another Intercept source. Two years after the Shadow Brokers leaks (and five years after his leaks), he was charged with five counts of taking and sharing classified documents, including two counts of 793e tied to 11 documents he took and shared with the Intercept. Three of the documents published by The Intercept were classified Top Secret.

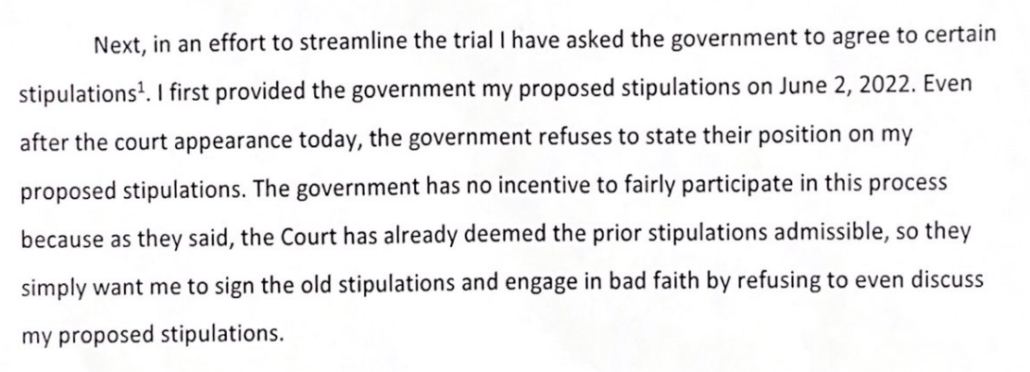

Hale pled guilty last year, just short of trial. As part of his sentencing process, the government argued that the baseline for his punishment should start from the punishments meted to those convicted solely of retaining National Defense Information. It tied Hale’s case to those of Martin and Pho explicitly.

Missing from Hale’s analysis are § 793 cases in which defendants received a Guidelines sentence for merely retaining national defense information. See, e.g., United States v. Ford, 288 F. App’x 54, 61 (4th Cir. 2008) (affirming 72-month sentence for retention of materials classified as Top Secret); United States v. Martin, 1:17-cr-69-RDB) (D. Md. 2019) (nine-year sentence for unlawful retention of Top Secret information); United States v. Pho, 1:17-cr-00631 (D. Md. 2018) (66-month sentence for unlawful retention of materials classified as Top Secret). See also United States v. Marshall, 3:17-cr-1 (S.D. TX 2018) (41-month sentence for unlawful retention of materials classified at the Secret level); United States v. Mehalba, 03-cr-10343-DPW (D. Ma. 2005) (20-month sentence in connection with plea for unlawful retention – not transmission – in violation of 793(e) and two counts of violating 18 U.S.C. 1001; court departed downward due to mental health of defendant).

Hale is more culpable than these defendants because he did not simply retain the classified documents, but he provided them to the Reporter knowing and intending that the documents would be published and made available to the world. The potential harm associated with Hale’s conduct is far more serious than mere retention, and therefore calls for a more significant sentence. [my emphasis]

Even in spite of a moving explanation for his actions, Hale was sentenced to 44 months in prison. Hale still has almost two years left on his sentence in Marion prison.

That focus on other retention cases from the Hale filing was among the most prominent national references to yet another case of someone prosecuted during the Trump Administration for taking classified files home from work, that of Weldon Marshall. Over the course of years of service in the Navy and then as a contractor in Afghanistan, Marshall shipped hard drives of classified materials home.

From the early 2000s, Marshall unlawfully retained classified items he obtained while serving in the U.S. Navy and while working for a military contractor. Marshall served in the U.S. Navy from approximately January 1999 to January 2004, during which time he had access to highly sensitive classified material, including documents describing U.S. nuclear command, control and communications. Those classified documents, including other highly sensitive documents classified at the Secret level, were downloaded onto a compact disc labeled “My Secret TACAMO Stuff.” He later unlawfully stored the compact disc in a house he owned in Liverpool, Texas. After he left the Navy, until his arrest in January 2017, Marshall worked for various companies that had contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense. While employed with these companies, Marshall provided information technology services on military bases in Afghanistan where he also had access to classified material. During his employment overseas, and particularly while he was located in Afghanistan, Marshall shipped hard drives to his Liverpool home. The hard drives contained documents and writings classified at the Secret level about flight and ground operations in Afghanistan. Marshall has held a Top Secret security clearance since approximately 2003 and a Secret security clearance since approximately 2002.

He appears to have been discovered when he took five Cisco switches home. After entering into a cooperation agreement and pleading guilty to one count of 793e, Marshall was (as noted above) sentenced to 41 months in prison. Marshall was released last year.

Outside DOJ, pundits have suggested that Trump’s actions are comparable to those of Sandy Berger, who like Trump stole files that belong to the National Archives and after some years pled guilty to a crime that Trump since made into a felony, or David Petraeus, who like Trump took home and stored highly classified materials in unsecured locations in his home. Such comparisons reflect the kind of elitist bias that fosters a system in which high profile people believe they are above the laws that get enforced for less powerful people.

But the cases I’ve laid out above — particularly the lesson Pho and Martin offer about how catastrophic it can be when someone brings classified files home and stores them insecurely, no matter their motives — are the background against which career espionage prosecutors at DOJ will be looking at Trump’s actions.

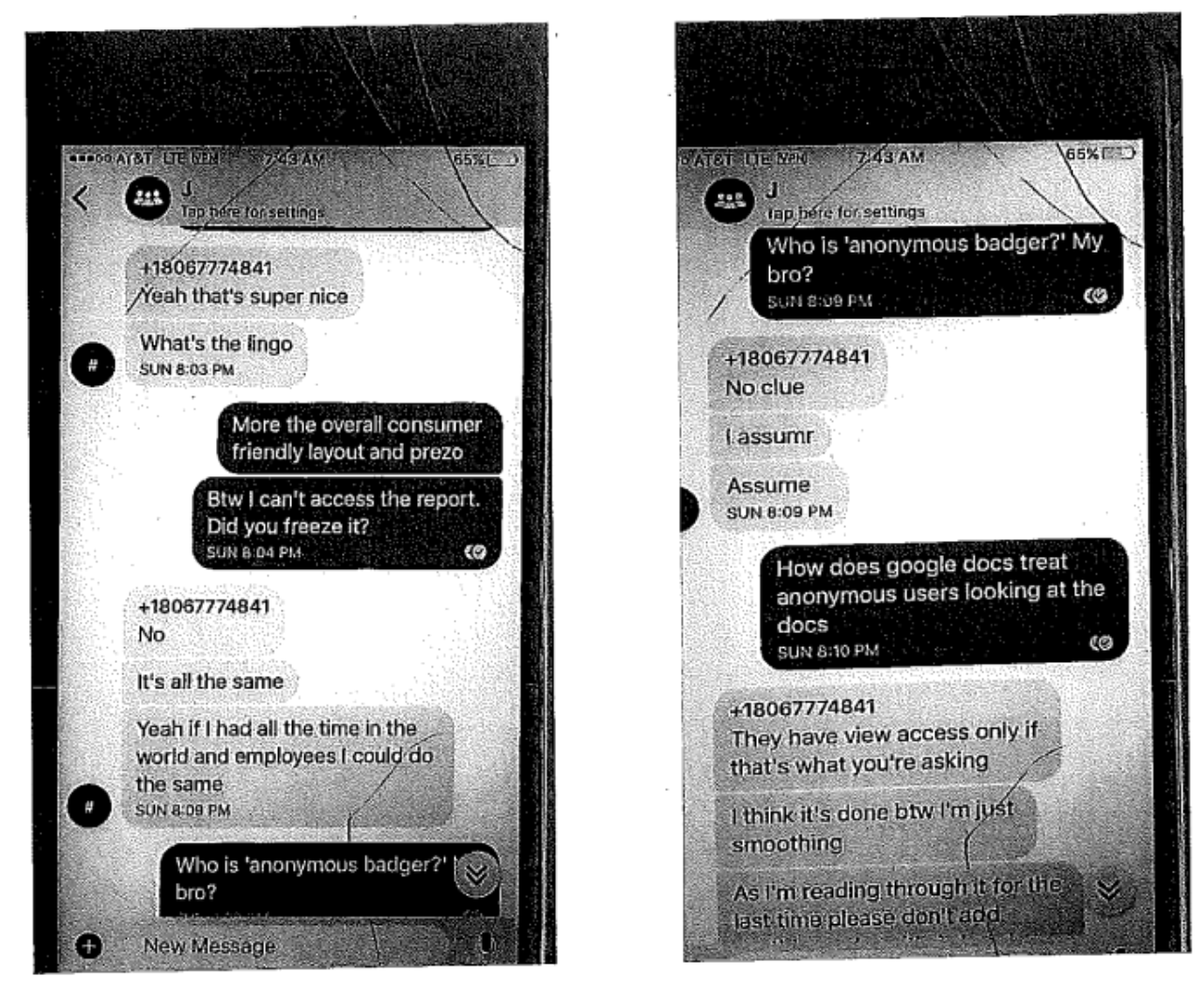

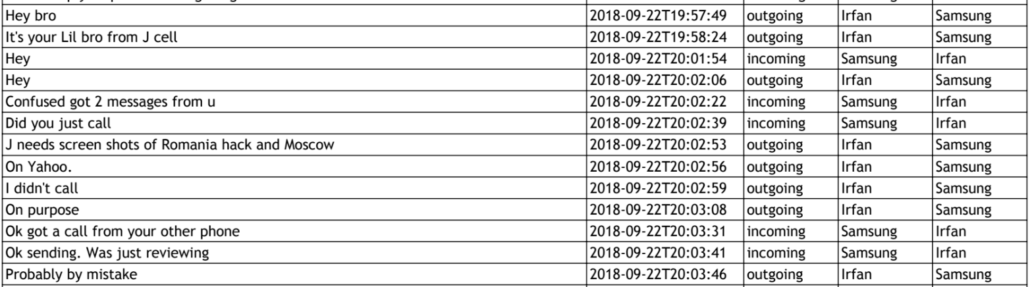

And while Trump allegedly brought home paper documents, rather than the digital files that Russian hackers could steal while sitting in Moscow, that doesn’t make his actions any less negligent. Since he was elected President, Mar-a-Lago became a ripe spying target, resulting in at least one prosecution. And two of the people he is most likely to have granted access to those files, John Solomon and Kash Patel, each pose known security concerns. Trump has done the analog equivalent of what Pho did: bring the crown jewels to a location already targeted by foreign intelligence services and store them in a way that can be easily back-doored. Like Pho, it doesn’t matter what Trump’s motivation for doing so was. Having done it, he made it ridiculously easy for malicious actors to simply come and take the files.

Under Attorneys General Jeff Sessions and Bill Barr, DOJ put renewed focus on prosecuting people who simply bring home large caches of sensitive documents. They did so in the wake of a costly lesson showing that the compromise of insecurely stored files can do as much damage as a high level recruited spy.

It’s a matter of equal justice that Trump be treated with the same gravity with which Martin and Pho and Albury and Hale and Marshall were treated under the Trump Administration, for doing precisely what Donald Trump is alleged to have done (albeit with far fewer and far less sensitive documents). But as the example of Shadow Brokers offers, it’s also a matter of urgent national security.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)