Judge in WikiLeaks FOIA Cites “Events that Have Transpired,” Government Claims FOIA Is “Improper”

Back in 2011, the Electronic Privacy Information Center sued to enforce a FOIA for documents on FBI’s investigation of WikiLeaks supporters. In response, the government cited an ongoing investigation exemption. But they also cited a statutory exemption, claiming some law prevented them from releasing the records on investigations into WikiLeaks supporters. Unusually, DOJ refused to name the law in question. For that reason, and because my suspicions of how Section 215 gets used suggested it would make a spectacular tool for investigating a group of WikiLeaks supporters, I suggested that the statute was likely Section 215.

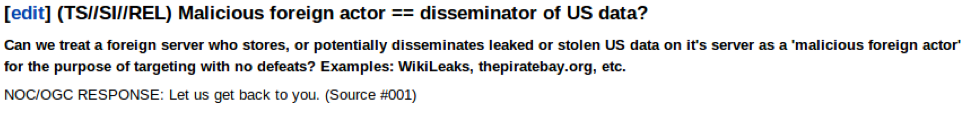

Since then, we’ve seen indications of NSA involvement in the investigation into WikiLeaks, though without any details from before EPIC’s FOIA.

And until March 11, that’s where things stood, with the government claiming it couldn’t release records about its investigation into completely innocent supporters of a publishing outlet and the judge (who had been newly assigned to the case in April 2013) doing nothing with the government’s motion for summary judgement.

On March 11, however, Judge Barbara Jacobs Rothstein ordered DOJ and EPIC to submit briefs updating her on the status of the investigation into WikiLeaks and with it the government’s ongoing investigation exemption, but not its claimed statutory exemption.

The Court takes judicial notice that events have transpired during that time that may cause the government’s position to to have changed. Therefore, the Court instructs the government to update its position regarding Plaintiff’s FOIA request, particularly with respect to the government’s invocation of exemption 7(A).

The language of her order suggests two things. First, if Rothstein is asking whether the 7(A) ongoing investigation exemption remains active, it suggests she’s may not accept the government’s statutory exemption 3 to completely withhold these documents. And she doesn’t say what the “events” that “have transpired” are, but it’s probably not any developments in the WikiLeaks investigation, as that’s what she says she doesn’t know. That makes it likely the Snowden leaks and related official disclosures have made the exemption 3, the basis for which she knows about from classified declarations, moot.

That’s all tea leaf reading. And even if I’ve read the tea leaves correctly, it doesn’t mean I’m right about Section 215. After all, back door searches on collection targeted at Julian Assange (who, as a foreign citizen and alleged spy, would be a legal target under Section 702 or even generally) would be a useful investigation into WikiLeaks supporters as well, though there’s abundant reason to believe dragnet queries serve as the basis for back door searches. Still, I think it’s likely that something that has been released and declassified since last April has mooted the government’s secret statutory claims.

The government, having sat on Judge Rothstein’s April 11 deadline from March 11 until Tuesday, is now stalling for time. (h/t JG; links to come shortly) On Tuesday, the lawyer who inherited this case claimed she has another case that prevents her from writing 10 pages on the status of the WikiLeaks investigation. But also that she needs more time to consult with the “defendant agencies.”

In addition, the draft supplemental brief will require review within the Department of Justice and defendant agencies before it may be filed.

EPIC’s not buying it, citing from the judge’s previous orders warning against extensions and stating clearly that business in other matters is not a good excuse. EPIC also described DOJ’s sleazy post-business hours effort to provide notice. and noted this is precisely the kind of thing Judge Rothstein had said would get a motion summarily denied.

Ms. Zeidner Marcus also did not timely notify Plaintiff’s counsel of her plans to file this Motion for Extension of Time. Ms. Zeidner Marcus first contacted Ms. McCall on April 8, 2014, the date that the filing was due, after ordinary business hours. Ms. Zeidner Marcus first emailed Ms. McCall on April 8, 2014 at 5:01 PM and followed up at approximately 5:30 PM that day with a telephone call. This did not give Ms. McCall sufficient time to consider Ms. Zeidner Marcus’ request or to consult with Ms. McCall’s co-counsel ,Mr. Rotenberg, regarding that request. Ms. Zeidner Marcus then filed her Motion for Extension of Time at 11:23 PM on the same day (April 8, 2014).

To which DOJ responded by accusing EPIC of filing an “improper” FOIA.

This case involves plaintiff’s attempts to improperly use the Freedom of Information Act to seek information about ongoing criminal investigations.

Remember, the underlying issue here is that DOJ shouldn’t be investigating innocent supporters of a publishing outlet. But DOJ believes trying to learn how and why they are doing so is an improper FOIA.

Meanwhile, DOJ sources admitted last November that they can’t really charge Assange without charging the NYT as well.

Justice officials said they looked hard at Assange but realized that they have what they described as a “New York Times problem.” If the Justice Department indicted Assange, it would also have to prosecute the New York Times and other news organizations and writers who published classified material, including The Washington Post and Britain’s Guardian newspaper, according to the officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

Which, I guess, explains the rudeness and urgent need for one more month. Because if the government loses both its ongoing investigation and its statutory exemptions, they might have to explain why they used national security tools against people exercising free speech.

Update: The Judge gave the government half the extension they requested, to April 25.

In light of the fact that the motion was not timely filed and that press of business is not an adequate reason for an extension, the Court will not grant the request for a thirty day extension. Instead, the Court will grant an extension to and including April 25, 2014. Plaintiff’s opposition shall be filed on or before May 12, 2014. The reply shall be file on or before May 19, 2014. In the future, the Court expects the parties to comply with the terms of the Standing Order in this case.