Nation Building with Special Forces

Nada Bakos tees up Jackson Diehl’s failed Iraq justification to fail again in Syria post and points out something very basic. Military intervention does not equate with nation-building.

It would be a plausible argument if Diehl had not clearly missed many of the most basic lessons of the Iraq War. For example, he writes that “in the absence of U.S. intervention, Syria is looking like it could produce a much worse humanitarian disaster and a far more serious strategic reverse for the United States.” It is certainly true that Syria is a humanitarian disaster on a regional scale, and that the lack of a clear strategy by the United States for the past two years has limited our ability to shape the nature and trajectory of the conflict today. But the phrase “in the absence of U.S. intervention” suggests a degree of American agency that Iraq showed we simply don’t possess.

Military intervention by the United States cannot spawn democratic governments at will, and it cannot save the local population from violence and chaos. “Shock and awe” do not automatically lead to nation-building or even to regime change without a considerable commitment. To realize those objectives, you need to engage in a clearly articulated strategy of nation-building — a strategy that must encompass the State Department; regional actors such as Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon (some of which are grappling with their own internal issues); and international, regional, and local non-governmental organizations.

[snip]

The argument that unleashing the U.S. military industrial complex can bring about desired results during a conflict should have been deflated, beaten, and buried by now. The winner of the Iraq War was humility, and it is a prerequisite for a wiser foreign policy.

Bakos’ retort is useful not just for those hawks who want more hot war in Syria, but also against plans to use the Special Forces as our primary tool against the scourge of instability, as promised in this NYT piece today …

Army Special Operations forces can be out there looking at instability, and looking at how to build capabilities.”

General Cleveland said he envisioned preparing his soldiers for two broad missions. “When I am at war, I have to campaign to win,” he said. “When I am not at war, I am campaigning to either shape the environment or I am campaigning to prevent war.”

And even more explicitly in this David Ignatius piece from last week.

The underlying idea is that special forces have proved themselves America’s best weapon against extremists in a turbulent, increasingly borderless world. After the grinding wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States won’t be sending big expeditionary armies abroad anytime soon. America’s heavyweight commands, such as U.S. Central Command in the Middle East and U.S. Pacific Command in Asia, will now focus on potentially adversarial nations such as Iran, China and North Korea.

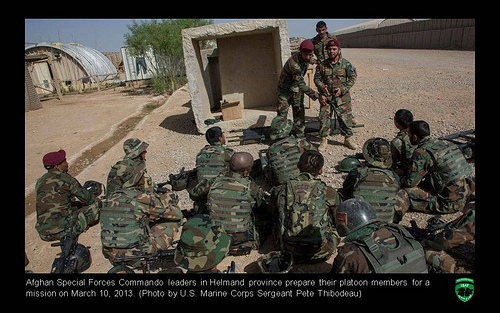

To fight the small wars, McRaven offers his agile, stealthy and highly lethal network of commandos. Often their missions will involve training and partnering with other nations, rather than shooting. Sometimes, their activities may look like USAID development assistance or CIA political action.

Here’s the logic: Our existing means of exerting influence and building nations aren’t all that effective, so we must have SOF take over those roles.

The existing tool kit hasn’t been very effective: USAID is more of a development contractor than an operational agency; the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations is too small to lead even its own department’s efforts, let alone the government’s; the U.S. Institute of Peace likes its status as an independent adviser, rather than an instrument of national power. And the CIA wants to do less covert action, not more.

Enter the Special Operations Forces.

Ignatius doesn’t apparently consider what Micah Zenko tweeted while watching a Chuck Hagel press conference and DOD cutbacks.

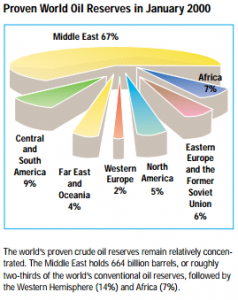

Pentagon will receive $633B this year. State+USAID: $51B. Internal DOD reforms don’t change the USG-wide imbalance.

You’d think someone (besides Zenko) would figure out that turning SOF warriors into development specialists would look at this math and propose more obvious solutions first.