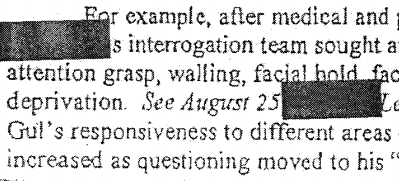

Update, March 12, 2015: We know from the Torture Report that the detainees treated in July and August 2004 were not Hasan Ghul, but Janat Gul and two others.

In my last post, I noted that in his report that Hassan Ghul served as a double agent before we offed him with a drone, Aram Roston stated, without confirming via sources, that Ghul is the person whose name was not entirely redacted on the bottom of page 7 in the May 2005 Convention Against Torture (CAT) torture memo. I noted that if Ghul is the detainee (and I do think he is, contrary to what sources told AP when the CIA was hunting Ghul down with drones in 2011), then we’re going to be hearing about him — and arguing about his treatment — quite a bit more in the coming weeks.

That’s because, according to information released by Mark Udall, the detainee named in the CAT memo is one of the detainees about whose treatment the CIA lied most egregiously to DOJ. This is apparently one of the key findings from the Senate Intelligence Committee Torture Report that CIA is fighting so hard to suppress.

Mark Udall’s list of torture lies

Back in August, Mark Udall posed a set of follow-up questions to then CIA and now DOD General Counsel Stephen Preston. Udall was trying to get Preston to endorse findings that appeared in the Torture Report that hadn’t appeared elsewhere (in his first set of responses about CIA’s lies to DOJ, Preston had focused on CIA’s lies about the number of waterboardings, which the CIA IG Report had first revealed). Udall noted that that lie (“discrepancy”) was known prior to the Torture Report, and asked Preston to review the “Representations” section of the Torture Report again to see whether he thought the lies (“discrepancies”) described there — and not described elsewhere — would have been material to OLC’s judgements on torture.

Udall gave Preston this list of OLC judgements that might have been different had CIA not lied to DOJ. (links added)

- Memorandum Regarding Interrogation of al Qaeda Operative (August 1, 2002);

- Letters from the Department of Justice related to the interrogation of individual detainees, including to the Acting Director of Central Intelligence, dated July 22, 2004; to the CIA Acting General Counsel, dated August 6, 2004; to the CIA Acting General Counsel, dated August 26, 2004; to the CIA Acting General Counsel, dated September 6, 2004; and to the CIA Acting General Counsel, dated September 20, 2004;

- Memorandum Regarding Application of 18 U.S.C. §§ 2340-2340A to Certain Techniques That May be Used in the Interrogation of a High Value al Qaeda Detainee (May 10, 2005) [Techniques]

- Memorandum Regarding Application of 18 U.S.C. §§ 2340-2340A to the Combined Use of Certain Techniques in the Interrogation of High Value al Qaeda Detainees (May 10, 2005) [Combined]

- Memorandum Regarding Application of United States Obligations Under Article 16 of the Convention Against Torture to Certain Techniques that May Be Used in the Interrogation of High Value al Qaeda Detainees (May 30, 2005) [CAT]

- Memorandum Regarding Application of the Detainee Treatment Act to Conditions of Confinement at Central Intelligence Agency Detention Facilities (August 31, 2006)

- Memorandum Regarding Application of the War Crimes Act, the Detainee Treatment Act, and Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions to Certain Techniques that May Be Used by the CIA in the Interrogation of High Value al Qaeda Detainees (July 20, 2007)

The 2002 memo is the original Abu Zubaydah memo, the lies in which (pertaining to who AZ was, what the torture consisted of, what had already been done to him, and whether it worked) I’ve explicated in depth elsewhere. The 2006 memo authorizes torture in the name of keeping order in confinement and the 2007 memo authorizes torture (especially sleep deprivation); both of these later memos not only rely on the 2005 memos, but on the false claims about efficacy CIA made in 2005 in their support. The lies in them pertain largely to the purpose CIA wanted to use the techniques for.

Which leaves the claims behind the 2004 letters and the 2005 memos as the key lies CIA told DOJ that remain unexplored.

The 2004 and 2005 lies to reauthorize and expand torture

I’m going to save some of these details for a post on what I think the lies told to DOJ might be, but there are two pieces of evidence showing that the 2005 memos were written to retrospectively codify authorizations given in 2004, many of them in the 2004 letters cited by Udall.

We know the 2005 memos served to retroactively authorize the treatment given to what are described as two detainees in 2004, purportedly in the months after July 2004 (though this may be part of the lie, in Ghul’s case) when DOJ and CIA were trying to draw new lines on torture in the wake of the completion of the CIA IG Report and Jack Goldsmith’s withdrawal of the Bybee Memo.

We know the May 10 Combined Memo was retroactive because Jim Comey made that clear in emails raising alarm about it.

I just finished a long call from Ted Ullyot. He said he was calling to tell me that “circumstances” were likely to require that the second opinion “be sent over tomorrow.” He said Pat had shared my concerns, which he understood to be concerns about the prospective nature of the opinion and its focus on “prototypical” interrogation.

[snip]

He mentioned at one point that OLC didn’t feel like it could accede to my request to make the opinion focused on one person because they don’t give retrospective advice. I said I understood that, but that the treatment of that person had been the subject of oral advice, which OLC would simply be confirming in writing, something they do quite often.

This memo probably, though not definitely, refers to a detainee captured in August 2004 in anticipation of what the Administration claimed (almost certainly falsely) were election-related plots in the US.

And we know the May 10 Techniques and May 30 CAT memos are retroactive because we can trace back the citations about the treatment of one detainee, the detainee who appears to be Ghul, to the earlier letters from 2004.

Just as an example, the August 26 letter cited in Udall’s list relies on the August 25 CIA letter that is also cited in the CAT Memo using the name Gul (the July 22 and August 6 letters are also references, at least in part, to the same detainee).

So we know the 2005 memos served to codify the authorizations for torture that had happened in 2004, during a volatile time for the torture program.

The description of Hassan Ghul in the lying memo

There are still some very funky things about these memos’ tie to Hassan Ghul (again, that’s going to be in a later post), notably that Bush figures referred to the Ghul of the August letters as Janat Gul, including in a Principals meeting discussing his torture on July 2, 2004; sources told the AP after OBL’s killing that this Janat was different than Hassan and different than the very skinny Janat Gul who had been a Gitmo detainee.

But this description — the timing of the initial references and the description of his mission to reestablish contact with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi — should allay any doubts that Ghul is one of two detainees referenced in the CAT memo.

Intelligence indicated that prior to his capture, [redacted] “perform[ed] critical facilitation and finance activities for al-Qa’ida,” including “transporting people, funds, and documents.” Fax for Jack Goldsmith, III, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, from [redacted] Assistant General Counsel, Central Intelligence Agency (March 12, 2004). The CIA also suspected [redacted] played an active part in planning attacks against United States forces [redacted] had extensive contacts with key members of al Qaeda, including, prior to their captures, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (“KSM”) and Abu Zubaydah. See id. [redacted] was captured while on a mission from [redacted] to reestablish contact with al-Zarqawi. See CIA Directorate of Intelligence, US Efforts Grinding Down al-Qa’ida 2 (Feb 21, 2004).

Ghul was captured by Kurds around January 23, 2004, carrying a letter from Zarqawi to Osama bin Laden.

So while there are a lot of details that the Senate Torture Report presumably sorts out in detail, it seems fairly clear that Ghul is the subject of some of the documents in question, and that, therefore, there are aspects of the treatment he endured at CIA’s hands that CIA felt the need to lie to DOJ about.

We’ve known for years that CIA lied to DOJ about what they had done and planned to do with Abu Zubaydah. But a great deal of evidence suggests that CIA lied to DOJ about what they did to Hassan Ghul, a detainee (the Senate Report also shows) who provided the key clue to finding Osama bin Laden before he was tortured.

If that’s the case, then I find the release of a story that, after that treatment, he turned double agent either directly or indirectly in our service to be awfully curious timing given the increasing chance we’re about to learn more about these lies and this treatment with any release of the Torture Report.