The New Bezzle

John Kenneth Galbraith gave us the term “the bezzle” in his 1955 book The Great Crash, 1929. Galbraith saw that there was often a long time between a financial crime and its discovery. In the interim holders of the financial asset involved in the crime experiences “psychic wealth”, because they are unaware of the actual losses. Eventually, something changes, and they find out. The Bernie Madoff case is a good example. Until he was exposed after the Great Crash, his loser investors thought they had $57 billion in their accounts. Turns out they had net recoveries of about $10 billion on the $17 billion they invested. That puts the bezzle at $47 billion.

Here’s another example. In the Antebellum South, there were nearly 4 million slaves with a value estimated at between $3.1 and $3.6 billion. After the war, that value went to zero. What was the net worth of the slavers in the late 1850s? They thought they were rich enough to battle the Union on equal terms, but the value of slaves wasn’t nearly equal to the value of the steel mills and industry of the northern states.

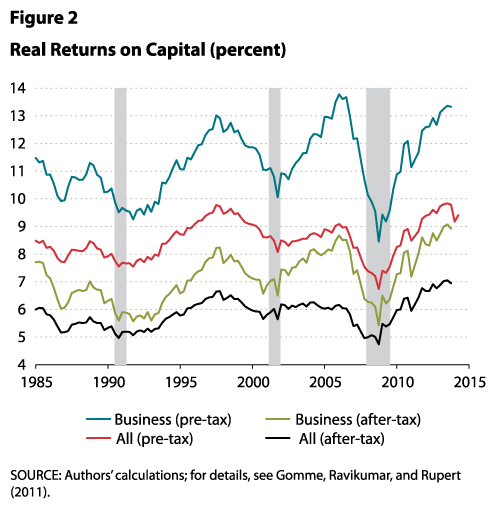

The problem of identifying the value of capital interests is very difficult. In Capital in the Twenty-First Century Piketty acknowledges the problem, and selects a solution appropriate to his purposes: the market valuations of the many forms capital can take. Here’s an excellent essay discussing this choice and its critics. By using this definition, Piketty simply ignores the problem of the bezzle, which makes sense in the terms of his project. Using Galbraith’s definition I suspect it wouldn’t make make a difference.

But I think the term leads us to a broader definition. The Great Crash provides a good example of what that new definition should be. The current estimate is that the Great Crash resulted in the loss of nearly 30% of household net worth between 2007 and 2010. The average household lost nearly $50 thousand in net worth between 2007 and 2010 according to the GAO report. Page 27 in the .pdf. By 2013, when markets were functioning — let’s say normally — the GAO estimated total household paper wealth losses at $9.1 trillion. Report here.

A large part of this paper loss was the decline in financial assets which affected people directly and through their pensions and retirement plans. Another large part was the result of lower house prices, which left many people with mortgage debt higher than the new prices. Here’s a priceless sentence from the report:

Economists we spoke with noted that precrisis asset prices may have reflected unsustainably high (or “bubble”) valuations and it may not be appropriate to consider the full amount of the overall decline in net worth as a loss associated with the crisis.

I bet the millions of people who lost that money don’t really care what economists think now, because none of the economists who could have made this stick before the Great Crash said this when it would have mattered. Far from it: the economics tribe insisted that markets were all-knowing and perfect in their understanding, and spent their days explaining why this time was different.

This superficial description shows that these households are in the same position as Madoff investors and Southern slavers: they thought they had something they didn’t, and they changed their behavior based on it.

I can just hear Paul Krugman explaining that bubbles and bezzles are really hard to model, and that’s why no one studies them. That’s probably true. Also, so what? Here’s my clever idea: look for data and see what it tells us. It worked for Piketty, who found that the historical record showed that inequality increases when r > g. Piketty and Saez, and Gabriel Zucman who did the estimate on tax shelters, didn’t have a model. They did have dusty records and big computer skills, just like all their contemporaries.

I hope that somewhere in academia there are young economists who look at Piketty, Saez and Zucman and their colleagues and say “I could do that”. And it’s just not that hard. Here are some hints.

1. There’s a big pile of student loan debt that isn’t going to be repaid. How much of that is on the books of the US Treasury, and how much is private sector? How much in the latter category is delinquent? Who holds it and in what form? If it’s in trusts, there isn’t going to be any enforcement, and the losses will fall on the owners of the securities. If it’s in the hands of originators, what happens to their balance sheets as this stuff cascades into default?

2. Every month we see another big business crash and burn. Often they fail because they are held by private equity investment firms. The crashes mean that a lot of debt isn’t going to be repaid. How big is that likely to be, and who’s going to eat that loss?

3. For the past 8 years or so, investors have been chasing yield. There’s some Galbraith bezzle in this stuff. How much dreck is sitting in their portfolios?

4. What does the rest of the mortgage overhang and related RMBS look like?

5. How much money is there in organized crime? A big part of the profits filters into the economy in the form of some kind of investment. How much of it is in the stock market? What happens when or if that ever gets traced and seized?

6. In the same way, how much have oligarchs and politicians stolen from other nations and moved into world financial markets? What happens if we got serious about that?

7. Another form of points 5 and 6: Rich people have stashed as much as $32 trillion in overseas tax shelters. If people got serious about this, their governments could seize this money and/or impose huge taxes on it. Say half of it, $16 trillion, got sucked up by taxation and seizure, and was removed from the financial markets and banks where it sits. What would happen then?

So, economists, just how big is the bezzle?