Stan Woodward Blows Off Any Duty of Loyalty to His Former Client

I noted yesterday that the government claimed that Stan Woodward had conceded he had a duty of loyalty to Yuscil Taveras that would limit what he could do in an eventual trial of Walt Nauta.

In his own response, however, Woodward makes no mention of any duty of loyalty to a former client. Instead, he engages in a great deal of word games to suggest precedents don’t apply to what he repeatedly describes as “[very] limited” representation of Taveras.

Instead, the Special Counsel’s Office seeks to micromanage defense counsel’s handling of any potential conflict arising from the trial testimony of a witness, which such witness benefited from limited former representation, no ongoing dual representation, no indication of conflict resulting from the representation itself, no indication of attorney-client privileged information at issue, and no occasion for crossexamination by the counsel in question (as co-counsel is available for the same).2

[snip]

[T]he very limited representation of an individual whom the Special Counsel’s Office wished to question in relation to a matter that later developed into a criminal prosecution of another client.

It’s a ploy used in Woodward’s surreply, as well.

The case at bar – involving limited former representation, no ongoing joint representation, no indication of conflict resulting from the representation itself, no indication of attorney-client privileged information at issue, and no occasion for cross-examination by the counsel in question (as other counsel is available for same) – is entirely incompatible with these cases and demonstrates the insubstantiality of the Special Counsel’s Office’s present use of a conflict rationale.

Even if it were the case that clients weren’t entitled to privilege if a representation was limited in time or scope, it ignores a very crucial detail of this case.

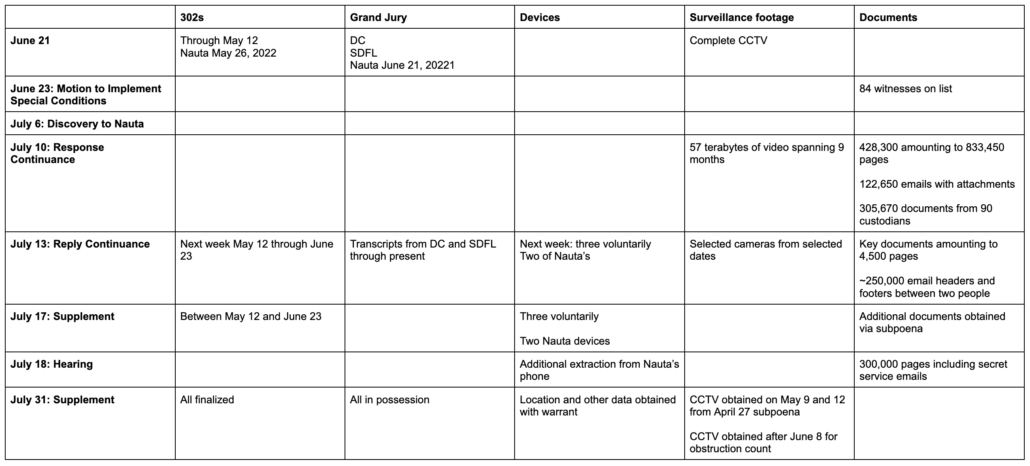

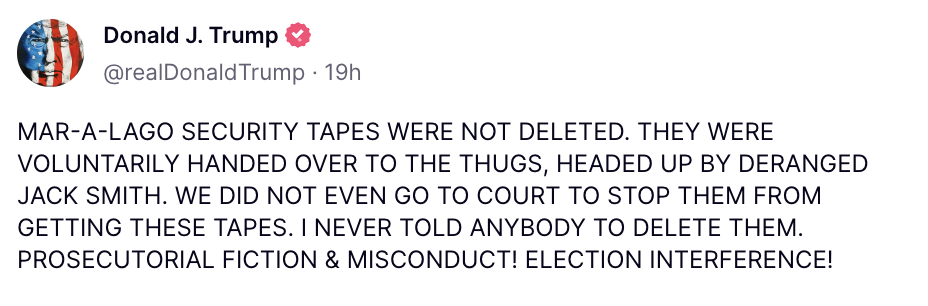

DOJ told Woodward he had a potential conflict before Taveras testified to the grand jury in March, where he denied knowing about the attempt to delete surveillance video.

In February and March 2023, the Government informed Mr. Woodward, orally and in writing, that his concurrent representation of Trump Employee 4 and Nauta raised a potential conflict of interest. The Government specifically informed Mr. Woodward that the Government believed Trump Employee 4 had information that would incriminate Nauta. Mr. Woodward informed the Government that he was unaware of any testimony that Trump Employee 4 would give that would incriminate Nauta and had advised Trump Employee 4 and Nauta of the Government’s position about a possible conflict. According to Mr. Woodward, he did not have reason to believe his concurrent representation of Trump Employee 4 and Nauta raised a conflict of interest.

The only way this representation would be so limited would be if Woodward did nothing to figure out what kind of legal exposure Taveras was facing in his March grand jury appearance.

Woodward continued to deny his representation of both Nauta and Taveras created a conflict even after DOJ gave Taveras a target letter — in part because he had advised Taveras that if he wanted to cooperate, he could get a different lawyer.

[T]he government provides no information to support their claim that [Taveras] has provided false testimony to the grand jury. While counsel does not preclude that the government may have provided more information to the Court ex parte, the government’s current representation that [Taveras] has clearly presented false or conflicting information to the grand jury is wholly unsupported by any information available to counsel. Further, even if [Taveras] did provide conflicting information to the grand jury such that could expose him to criminal charges, he has other recourse besides reaching a plea bargain with the government. Namely, he can go to trial with the presumption of innocence and fight the charges as against him. If [Taveras] wishes to become a cooperating government witness, he has already been advised he may do so at any time.

[snip]

Ultimately, [Taveras] has been advised by counsel that he may, at any time, seek new counsel, and that includes if he ultimately decided he wanted to cooperate with the government.

Woodward seems to suggest that Taveras has waived his privilege because he told prosecutors what advice Woodward had given him.

Because it appears that the Special Counsel’s Office well knows what was disclosed to defense counsel by Trump Employee 4, the Special Counsel’s Office cannot maintain its position that the revelation of the same is barred. Put differently, the assertion of the Special Counsel’s Office of a presumption of continuing privilege in this context, where the Special Counsel’s Office sought and obtained new counsel for Trump Employee 4 for the purpose of providing a means for Trump Employee 4’s testimony to change, and for his prior assertions to be explained by him—all of which was done not in the District where this case is pending, but in a faraway District, raising separate issues of grand jury misconduct—warrants development of the record at a hearing so as to ascertain to what extent any applicable privilege has been waived by Trump Employee 4’s disclosures to the Special Counsel’s Office. At a minimum, if the Special Counsel’s Office persists in asserting that privileged information remains, an evidentiary hearing is warranted as to what the Special Counsel’s Office is withholding regarding Trump Employee 4, his claims as to prior representation, and whether there has been any failure to disclose such matters to the Special Counsel’s Office.

Here, Woodward fashions privilege to consist only of confidentiality, not loyalty. And he suggests that because Taveras has shown some kind of disloyalty to him, he doesn’t owe any back.

In the filing, Woodward makes an oblique reference to Beryl Howell’s ruling finding Evan Corcoran’s advice to Trump to be crime-fraud excepted (though as he always does, he calls the underlying grand jury investigation in this very case a “faraway” District).

[I]t is noteworthy that in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia the Special Counsel’s Office has taken precisely the opposite position with respect to privileged communications. Specifically, in that District, the Special Counsel’s Office took the position that where a witness represented by counsel in a government compliance matter is not forthcoming with their counsel, a crime-fraud exception applies, voiding the attorney-client privilege. While Mr. Nauta vehemently opposes any application of the crime-fraud rulings made in a faraway District to this case, it is nevertheless impermissible for the Special Counsel’s Office to tailor the positions it takes before courts and/or grand juries in the various Districts where it seeks an advantage in its prosecution of former President Trump and his coconspirators.

This appears to be an attempt to liken Trump’s affirmative lies to Corcoran to Taveras’ own communications with him.

But, particularly with the demand for a hearing to find out what Taveras has told SCO about Woodward’s advice to him, it comes off as flopsweat about his, Woodward’s, own conduct.