Among the more trollish arguments in Yevgeniy Prigozhin’s latest troll argument in defense of his troll attack on the 2016 election is that Prigozhin has to get all the discovery turned over to Concord’s lawyers because only he can tell whether he’s Putin’s boss, or his chef.

[T]he documents that the government appears to contend are statements of Concord under Fed. R. Civ. P. 16(C)(i) and (ii) are primarily in Russian. While defense counsel has engaged translators to begin its review of the discovery materials, the only way to get fully accurate translations and prepare for trial is to speak to the individuals who allegedly wrote the documents. See United States v. Archbold-Manner, 577 F. Supp. 2d 291, 292-93 (D.D.C. 2008) (noting the need for translations of voluminous foreign language discovery in ruling relating to Speedy Trial Act). This is particularly true with respect to Russian, which is highly dissimilar to English and literal translations of words often result in lost meaning or context. See, e.g., https://www.state.gov/m/fsi/sls/c78549.htm (Department of State’s Foreign Service Institute School of Language Studies identifying Russian as a Category III Language “with significant linguistic and/or cultural differences from English”). Again, by way of example, certain allegedly sensitive documents contain the Russian word “шеф.” This word can be translated into the English words “chief,” “boss” or “chef”—a distinction that is critically important since international media often refers to Mr. Prigozhin as “Putin’s Chef.”

Each logical step in this paragraph is nonsense, because it’s clear the documents in question are getting translated by people who do not suffer from the “significant linguistic and cultural differences” cited by the State Department in an off-point citation. Ultimately, this argument amounts to Prigozhin claiming that only he knows whether — all this time! — has has actually been Putin’s boss, not his chef, as usually claimed.

That said, the argument is telling, because it suggests that Prigozhin has to get discovery because documents turned over in discovery directly implicate his relationship with Putin.

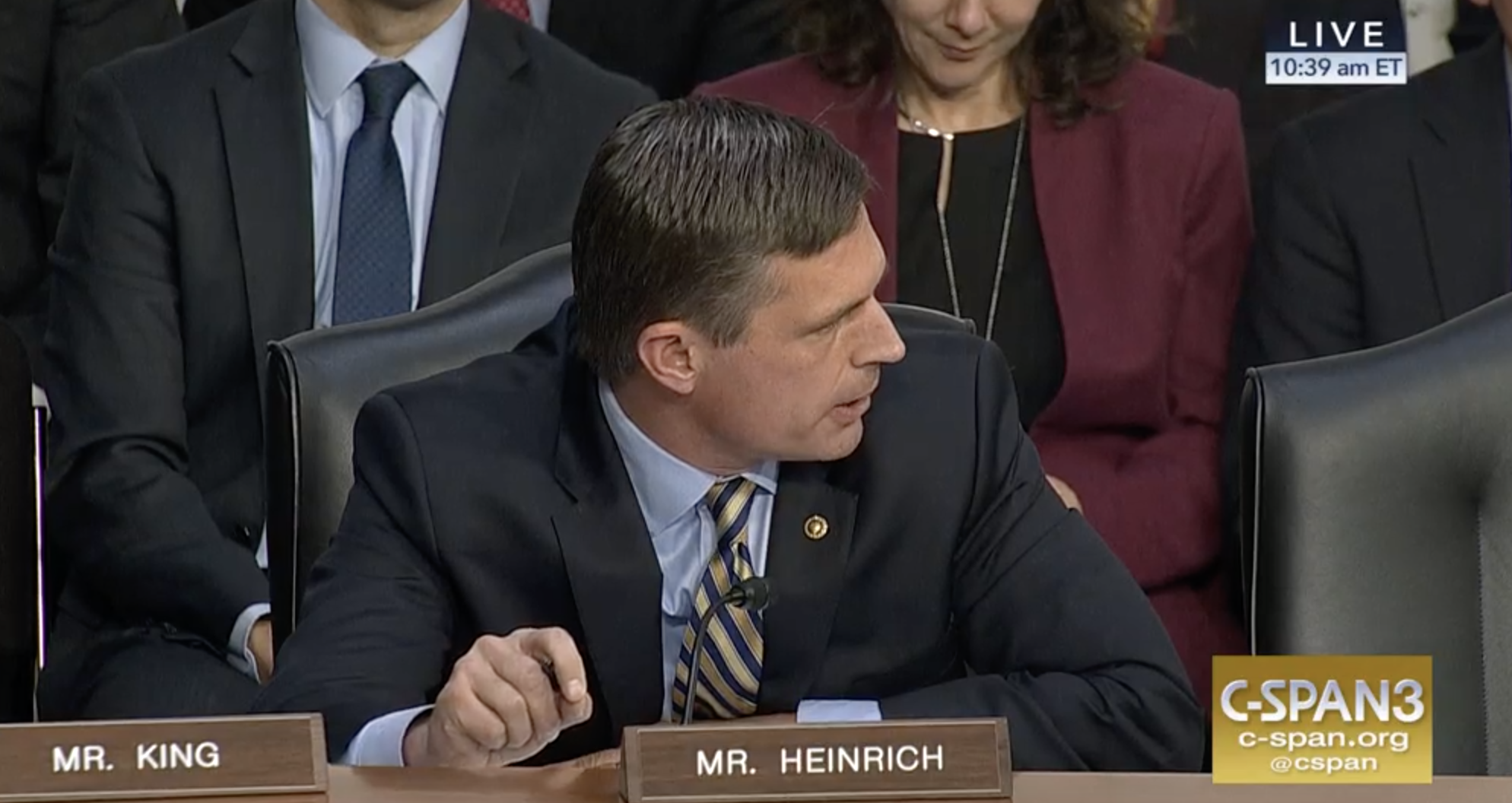

“The Russian national who controls the Defendant but has not personally appeared”

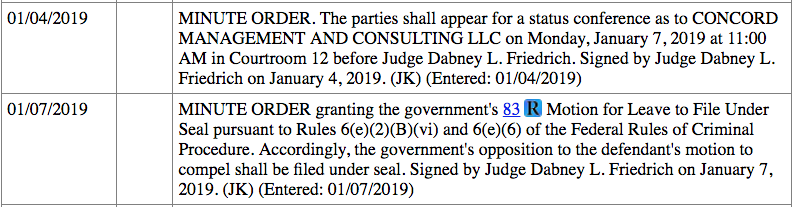

The main gist of this filing, however, is an attempt to revisit an earlier order in this case and force the government (the troll lawyers pretend this case is being exclusively prosecuted by Mueller and not also by lawyers from two other DOJ components) to turn over 3 million pages in discovery to Prigozhin, even though he hasn’t appeared before the court personally.

Since the entry of the Protective Order, the Special Counsel has produced nearly 4 million documents, 3.2 million of which it has designated as “sensitive.” The Special Counsel has not explained to defense counsel the reason for the designation of any particular document or category of documents, nor has he explained why—with non-classified material—defense counsel should not have access to his secret communications with the Court.

Remember, Prigozhin made himself General Manager of Concord Management after it got indicted in the same indictment in which he got indicted so he could insist that he get this discovery in his corporate form, even while dodging prosecution in his natural form (it’s sort of the reverse effect of the Trump Organization consubstantiation that is going to get Trump in trouble). As a result, Concord argues (for the second time) that Prigozhin must get discovery because he is the defendant, and not a co-defendant currently avoiding any court appearance.

Undersigned counsel has been unable to identify a single reported case where a corporate defendant was prohibited from viewing discovery,

[snip]

Second, co-defendant Mr. Prigozhin is the only person directly affiliated with Concord identified in the Indictment. As such, Concord cannot be expected to make informed decisions regarding its defense or meaningfully confer with its counsel unless it—and specifically Mr. Prigozhin—understands the evidence the Special Counsel intends to use against it at trial. Maury, 695 F.3d at 248 (recognizing that “[a]n organization has no self-knowledge of its own Undersigned counsel has been unable to identify a single reported case where a corporate defendant was prohibited from viewing discovery,

Yet the troll lawyers don’t address the issue that proved key the last time: that this an attempt for Prigozhin, who because he has not made an appearance is not bound by the protective order, to obtain discovery as a defendant without risking his neck. Indeed, it turns that scenario on its head, searching for instances where corporations have been denied discovery as opposed to where indicted co-conspirators obtain discovery without showing up in court first.

In a related filing, the government calls Prigozhin “the Russian national who controls the Defendant but has not personally appeared” and cite national security concerns about “certain facts regarding Prigozhin and other Russian nationals associated with him.” Perhaps the government needs to present details to Friedrich about just what Putin’s chef has cooked up for him.

The troll lawyers also don’t address the terms of the discovery order. Prigozhin has a means of getting the discovery he wants: he only needs to come to the United States and enter into the protective order to do that. Indeed, two of the cases Concord cites seem to support the existing protective order, which requires those who access this information to be bound by the court before they do so and prohibits discovery from being removed from the US.

United States v. Carriles, 654 F. Supp. 2d 557, 562, 570 (W.D. Tex. 2009) (rejecting the government’s proposed protective order related to sensitive but unclassified discovery which would have prevented defendant from disseminating any sensitive discovery material to prospective witnesses without first obtaining court approval, and instead allowing defendant to disclose materials necessary for trial preparation after obtaining a memorandum of understanding related to the protective order); Darden, 2017 WL 3700340, at *3 (rejecting the government’s proposed protective order that prohibited the defendants from reviewing discovery materials unless in the presence of counsel and adopting a less restrictive protective order which specified precisely which discovery materials defense counsel could review with the defendants but could not provide or leave with the defendants).

Admittedly, Judge Dabney Friedrich invited Concord to return to these issues (albeit at a slightly later stage than where we’re at). But Concord doesn’t even address that there are means for Prigozhin to access materials under the existing protective order.

There are two more interesting sub-arguments here.

Concord argues that because the US government has charged accountant Elena Khusyaynova — but not in this case — the ongoing investigation is done

First, Concord uses the fact that Eastern District of VA charged Concord accountant in a parallel case, the “ongoing investigation” the government cited to justify its secrecy has ended.

Nevertheless, the Special Counsel has publicly invoked—in the Protective Order itself and its briefing—both an “ongoing investigation” and “sensitive investigatory techniques” as grounds for preventing disclosure, neither of which should apply here.

Undersigned counsel must assume for now that the “ongoing investigation” referred to in the Protective Order is related to the criminal complaint recently unsealed in the Eastern District of Virginia. Ex. A. Because this complaint is now unsealed, and the ongoing investigation has been publicly revealed, there is no further need to protect this investigation from disclosure.

It later says that some of the documents cited in the affidavit submitted in Elena Khusyaynova’s case are “the very same documents” turned over in discovery here.

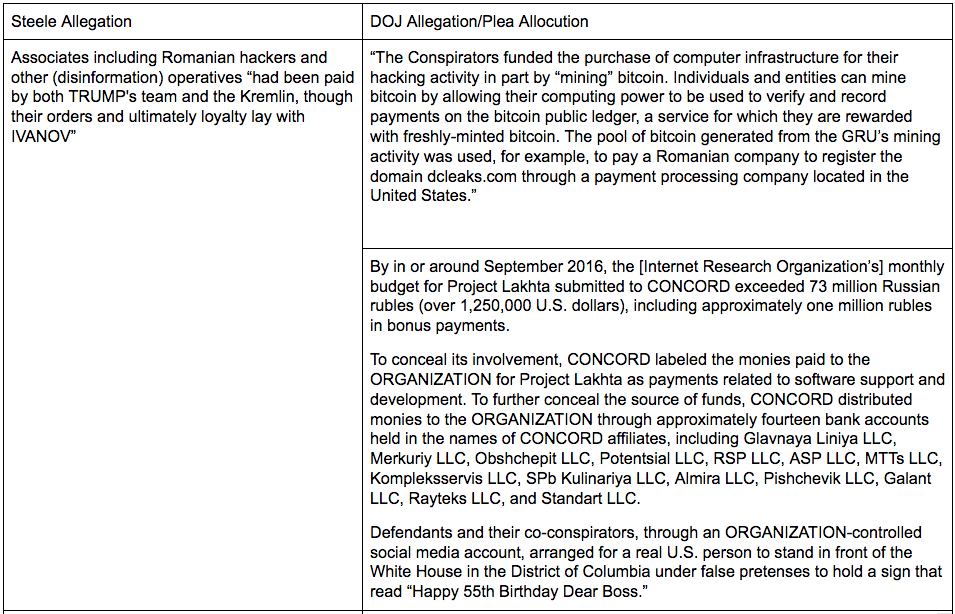

Relatedly, the government itself has described some of the “sensitive” discovery in great detail in public filings, yet has made no effort to subsequently re-categorize those very same documents as no longer sensitive. For example, in an affidavit in support of a criminal complaint filed under seal on September 28, 2018 in the Eastern District of Virginia and unsealed on October 19, 2018, an FBI Special Agent described “detailed financial documents that tracked itemized Project Lakhta expenses” allegedly transmitted between an employee of Concord and an employee of its co-defendant, Internet Research Agency. See Ex. A, Criminal Compl., United States v. Elena Khusyaynova, 1:18-mj-464 (E.D. Va.) (filed Sept. 28, 2018; unsealed Oct. 19, 2018) (“the Holt Affidavit”). The Holt Affidavit goes on to state that “[b]etween at least January 2016 and July 2018, these documents were updated and provided to Concord on approximately a monthly basis,” and provides “illustrative examples” of these documents, including identifying the individual who sent the document (the defendant identified in the complaint); describing the date on which the documents were allegedly sent and the approximate dollar value contained in the document; and even quoting from the documents. Id. ¶ 21. To the extent that these very same documents are among those designated by the Special Counsel as “sensitive,” it is impossible to understand why they cannot be shared with Concord in order to defend itself against criminal charges in this case. [my emphasis]

The argument that any investigation into Concord is complete is undermined by the other motion Concord submitted the same day they submitted this motion. It complains that Mueller prosecutor Rush Atkinson somehow took investigative action on information a week after Concord provided the same information to the Firewall Counsel, on August 30.

On August 23, 2018, in connection with a request (“Concord’s Request”) made pursuant to the Protective Order entered by the Court, Dkt. No. 42-1, Concord provided confidential information to Firewall Counsel. The Court was made aware of the nature of this information in the sealed portion of Concord’s Motion for Leave to Respond to the Government’s Supplemental Briefing Relating to Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss the Indictment, filed on October 22, 2018. Dkt. No. 70-4 (Concord’s “Motion for Leave”). Seven days after Concord’s Request, on August 30, 2018, Assistant Special Counsel L. Rush Atkinson took investigative action on the exact same information Concord provided to Firewall Counsel. Undersigned counsel learned about this on October 4, 2018, based on discovery provided by the Special Counsel’s Office. Immediately upon identifying this remarkable coincidence, on October 5, 2018, undersigned counsel requested an explanation from the Special Counsel’s Office, copying Firewall Counsel on the e-mail. The Special Counsel’s Office responded to the email on October 7, 2018, but did not explain how it obtained the confidential information, stating instead that the trial team was unaware that undersigned counsel was in communication with Firewall Counsel and that “[n]o criminal process that has been turned over in discovery is derived from [those] communications.”

Having received no further explanation or information from the government, undersigned counsel raised this issue with the Court in a filing made on October 22, 2018 in connection with the then-pending Motion to Dismiss. In response to questions from the Court, Firewall Counsel denied having any communication with the Special Counsel’s Office.

In a footnote, Concord makes the kind of vague claim I expect to be corrected by Mueller, suggesting that its one request to Firewall Counsel hasn’t gotten a response.

Concord initially requested authorization from the Court pursuant to the Protective Order to disclose a small number of specifically identified allegedly sensitive documents to particular Russian individuals, but to date the Court had not required the Firewall Counsel to respond to that request in writing.

While it’s certainly possible Atkinson’s investigative action fed into the September 28 charges against Khusyaynova, one way or another, it suggests the parts of the Concord investigation under Mueller also remain ongoing.

Interestingly, Atkinson wasn’t on October 23 and November 27 filings in this case, though he was on yesterday’s brief; during October and November, however, Atkinson was dealing with red-blooded American trolls like Jerome Corsi.

In any case, the complaint about Atkinson feels like a parallel construction issue to me. After all, Concord surely remains under close surveillance by the US government, and so long as Progozhin does not have a lawyer who files an appearance for him personally in this matter, he likely remains a legitimate surveillance target. So Atkinson might have means to obtain such information independent of the Firewall Counsel.

Reverse engineering the parallel construction on 3 million documents

Indeed, that’s what this entire thing feels like: an attempt to obtain the non-classified discovery from US providers to reverse engineer it to understand what surveillance the underlying investigation is conducting. As Concord describes, its lawyers are seeing millions of documents obtained via subpoena.

The Special Counsel has explicitly acknowledged that none of the discovery is classified. Moreover, the allegedly “sensitive” discovery appears to have been collected exclusively through the use of criminal subpoenas, search warrants, and orders issued pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 2703, as opposed to any classified collection method.

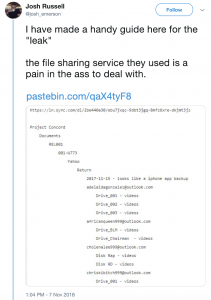

It then goes on to suggest that what US tech companies turn over in response to legal process is all laid out in public. It also helpfully names a bunch of providers from which discovery has been provided: Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Microsoft, Yahoo!, Instagram, WhatsApp, Paypal, and Verizon.

With respect to “sensitive investigatory techniques,” the discovery produced to date comes from legal process issued to various companies, including email providers, internet service providers, financial institutions, and other sources. See Government’s Mot. For a Protective Order Under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 16(d)(1) at 2, Dkt. 24. But any person anywhere in the world connected to the Internet already knows that law enforcement agencies can and do gather evidence from these types of companies through legal process in criminal matters, and specifically what can be gathered through those various processes is widely known and is not in need of protection. For example, Google explains in detail on its website precisely what information it will disclose in response to legal process in the form of a subpoena, court order, or search warrant. See https://support.google.com/transparencyreport/answer/ 7381738?hl=en. Google specifically publicizes that in response to a subpoena for Gmail data, it can be compelled to disclose subscriber registration information (e.g., name, account creation information, associated email addresses, phone number), and sign-in IP addresses and associated time stamps. Id. In response to a court order for Gmail data, Google may provide “non-content information (such as non-content email header information)” and in response to a search warrant Google can be compelled to produce email content, in addition to the data produced in response to a subpoena or court order. Id. Facebook publishes similar information, explaining that in response to a subpoena, it may disclose “basic subscriber records,” which may include name, length of service, credit card information, email addresses, and recent login/logout IP addresses. See https://www.facebook.com/safety/groups/law/guidelines/. In response to a court order, Facebook may disclose message headers and IP addresses, as well as basic subscriber records. Id. In response to a search warrant, Facebook may disclose stored contents of the account, including messages, photos, videos, timeline posts, and location information. Id.

Twitter, Apple, Microsoft, Yahoo!, Instagram, and WhatsApp, all publish similarly detailed information about the types of data available to law enforcement through subpoenas, court orders, and search warrants. See https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/twitter-lawenforcement-support (explanation from Twitter that obtaining non-public information requires valid legal process like a subpoena, court order, or other legal process and that requests for the contents of communications require a valid search warrant or equivalent); https:// www.apple.com/privacy/government-information-requests/ (explanation from Apple, Inc. of what government and law enforcement agencies can obtain through legal process); https:// www.microsoft.com/en-us/corporate-responsibility/lerr (explanation from Microsoft that a subpoena is required for non-content data, and a warrant or court order is required for content data); https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=A0geK.OJvA5cPPUAkCJXNyoA;_ylu= X3oDMTEyaDM4Z2dkBGNvbG8DYmYxBHBvcwMxBHZ0aWQDQjQ4NTNfMQRzZWMDc3I-/RV=2/ RE=1544498442/RO=10/RU=https%3a%2f%2fwww.eff.org%2ffiles%2ffilenode%2fsocial_net work%2fyahoo_sn_leg-doj.pdf/RK=2/RS=sXU4pB1SMj3WwjZBx3ltlU4S6v w- (explanation from Yahoo of precisely what data may be disclosed in response to a subpoena, 2703(d) order, or Search Warrant); https://faq.whatsapp.com/en/android/26000050/?category=5245250 (explanation from WhatsApp detailing what information is available through various forms of legal process); https://help.instagram.com/494561080557017 (explanation from Instagram describing the information it will disclose in response to subpoenas, search warrants, and court orders). Financial institutions and internet service providers also openly describe what information is available to law enforcement through various legal process. See, e.g., https://www.paypal.com/us/webapps/mpp/law-enforcement (explanation from PayPal describing the type of data it collects and when that data is made available to law enforcement as required by law); https://www.verizon.com/about/portal/transparency-report/faqs/ (explanation from Verizon of the types of information it is required to disclose when properly requested by law enforcement or court order).

Thus, if it is the so-called “manner of collection” of the discovery that the Special Counsel seeks to protect—that is, the fact that law enforcement agencies can collect a certain type of data—that fact is widely known and does not justify the burdens the Protective Order imposes on Concord’s right to present a defense.3

Concord goes on to dismiss the concerns of exposing “witnesses.”

3 To the extent that the government argues that limiting access to discovery will ensure the safety of witnesses, there is no valid basis for such argument. Specifically, even in cases where there is such a risk (and undersigned counsel knows of no such risk here), there must be more than “broad allegations of harm, unsubstantiated by specific examples or articulated reasoning.” Johnson, 314 F. Supp. 3d at 251. In those instances, courts are still willing to allow a defendant to review the evidence, subject to certain parameters. See, e.g., id., at 254 (requiring government redaction of discovery materials); Darden, 2017 WL 3700340, at *3 (adopting less-restrictive measure to ensure witness safety). If the government has a legitimate concern about witness safety, the burden is on it to specifically articulate the concern, identify precisely the documents that would lead to the identification of a witness, and redact that information or propose an alternative means of restricting disclosure.

The FBI hides a great deal of detail about precisely what it can obtain from providers by deeming service providers witnesses, and this feels like the same.

Still, even the public record in past dockets reveals that discovery from providers can be vastly more extensive than the public imagines.

Which is, I imagine, what Concord is trying to provide Putin’s chef.

The troll lawyers implicitly troll Judge Freidrich’s past rulings

Don’t get me wrong. What kind of protective order Friedrich sustains against Concord so long as it insists co-defendant Prigozhin is the only one at Concord who can handle that discovery is an interesting legal question.

That said, Concord’s signature style might start wearing on Friedrich’s patience given claims that seemingly defy her decision on the last major challenge to the Mueller prosecution.

In this first-of-its-kind prosecution of a make-believe crime, the Office of Special Counsel maintains that it can unilaterally—and for secret reasons disclosed only to the Court— categorize millions of pages of non-classified documents as “sensitive,” and prohibit defense counsel from sharing this information with Defendant Concord for purposes of preparing for trial. This, apparently only because the Defendant and its officers and employees are Russian as opposed to American. The Special Counsel’s unique argument appears rooted in the maxim, “Happy the short-sighted who see no further than what they can touch.”1

Maillart, Ella K., The Cruel Way (1947).

Friedrich has already ruled that this is not a made-up crime.

In Concord’s view, that omission is dispositive: the indictment cannot accuse Concord of conspiring to obstruct lawful government functions “without any identified or recognized statutory offense” because a conspiracy conviction cannot be “based strictly on lawful conduct” even if that conduct is “concealed from the government.” Id. (emphasis omitted).

Concord is correct that the indictment must identify the lawful government functions at issue with some specificity. And it does. See Indictment ¶¶ 9, 25–27. A defraud-clause conspiracy need not, however, allege an agreement to violate some statutory or regulatory provision independent of § 371. 3

[Citations of 5 cases demonstrating the point]

Put simply, conspiracies to defraud the government by interfering with its agencies’ lawful functions are illegal because § 371 makes them illegal, not because they happen to overlap with substantive prohibitions found in other statutes.

Similarly, as part of a complaint that the prosecutors haven’t had to bear any burden of this protective order, Concord says they should have to redact Personally Identifiable Information rather than deeming materials including it “sensitive.”

But rather than impose on the government the burden of identifying the materials that actually contain PII, so that the specific documents or information can be redacted or restricted, the Special Counsel has used the Protective Order to designate the entirety of various data productions to completely restrict Concord’s ability to view the vast majority of discovery regardless of whether specific documents contain PII.

This is another issue that Friedrich has already ruled against the defense on, ruling against their request to make Mueller strip the PII.

Friedrich already seemed predisposed to honor the government’s security concerns, which they just teed up again. If she feels like she’s the one being trolled, as opposed to Democratic voters or Special Counsel lawyers, she may not look too kindly on this request.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.