The Webster Report Recommendations and FBI’s Federated Back Door Searches

Back in 2013, in the context of a discussion of back door searches, I noted William Webster’s reference, in his report on the Nidal Hasan investigation, to using FISA communications with key targets as tripwires for further investigation, The following spring, in response to Bob Litt’s proclamation that it would be “impracticable” to require the government to count back door searches, I returned to Webster’s recommendations on fixing FBI’s archaic database access to make it easier to match communications from the same user (starting at 140). I suggested that back door searches — particularly their expansion in 2011 — might be a response to his recommendations.

To be fair, I suspect one of the issues is that after the Nidal Hasan attack (and this is just a very well educated guess), NSA rolled out a system whereby new communications between a targeted foreigner and an American automatically pulls up all previous communications involving that US person. That would count as a search, even though it would effectively feel like an automatic cross-referencing of all prior communications involving someone talking to a target, even if that is a US person.

Nevertheless, this means that NSA is conducting so many back door searches on US person data that it would be “impracticable” to actually give those searches some kind of review.

Not long after this hearing, we learned FBI was the agency for which it was impracticable to count back door searches, not NSA.

In the FISA court hearing on October 20, 2015 over whether FBI should provide individual justifications for back door searches, one of the government’s [redacted] lawyers explained that the way federated searches integrate back door searches indeed did come directly from the Webster Report recommendations.

To use an example more recent and even more on point, the Webster Commission’s report on the Fort Hood attack criticized the government’s queries of information in its possession. The people doing the assessment of Nidal Hasan did not identify several messages between Anwar Aulaqi and Nidal Hasan, and the commission deemed it essential that the FBI possess the ability to search all of its repositories and to do so without balkanizing those data sources.

And so these systems that do these federated queries that allow us to, yes, to query the 702 information, but all of these sources are in direct response to those findings, and they’re in direct response to our efforts over the last 15 years to bring down this artificial wall between the law enforcement mission of the FBI and its national security intelligence mission.

Reading this transcript reminded me that, back in 2014, I imagined all this would be automatic — not so much a search, but an interlinked search that would automatically pull up existing content.

There’s reason to believe that model, and the back door access at CIA and NSA to content (which was approved in 2011), was designed to work similarly.

One of the documents recently liberated by ACLU makes it clear that NSA’s metadata back door searches of 702 content are, in some way, automated, such that counts of such queries are counted using algorithms and business rules.

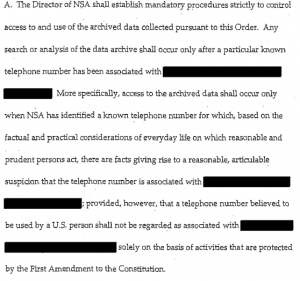

NSA will rely on an algorithm and/or a business rule to identify queries of communications metadata derived from the FAA 702 [redacted] and telephony collection that start with a United States person identifier. Neither method will identify those queries that start with a United States person identifier with 100 percent accuracy.

The I Con the Record report notes the back door content search number, which combined CIA and NSA, is also an estimate, which may suggest it is also counted algorithmically as well (though these are reviewed more closely in compliance reviews). In any case, CIA’s switch from counting each query using a US person identifier to counting each US person identifier queried leads me to suspect it — and NSA — use more of a tasking model, where certain US person identifiers automatically trigger for the period they’re tasked; at the NSA, at least, the duration of approval to do back door searches is either tied to the underlying probable cause FISA order or to a deadline set by the approving authority.

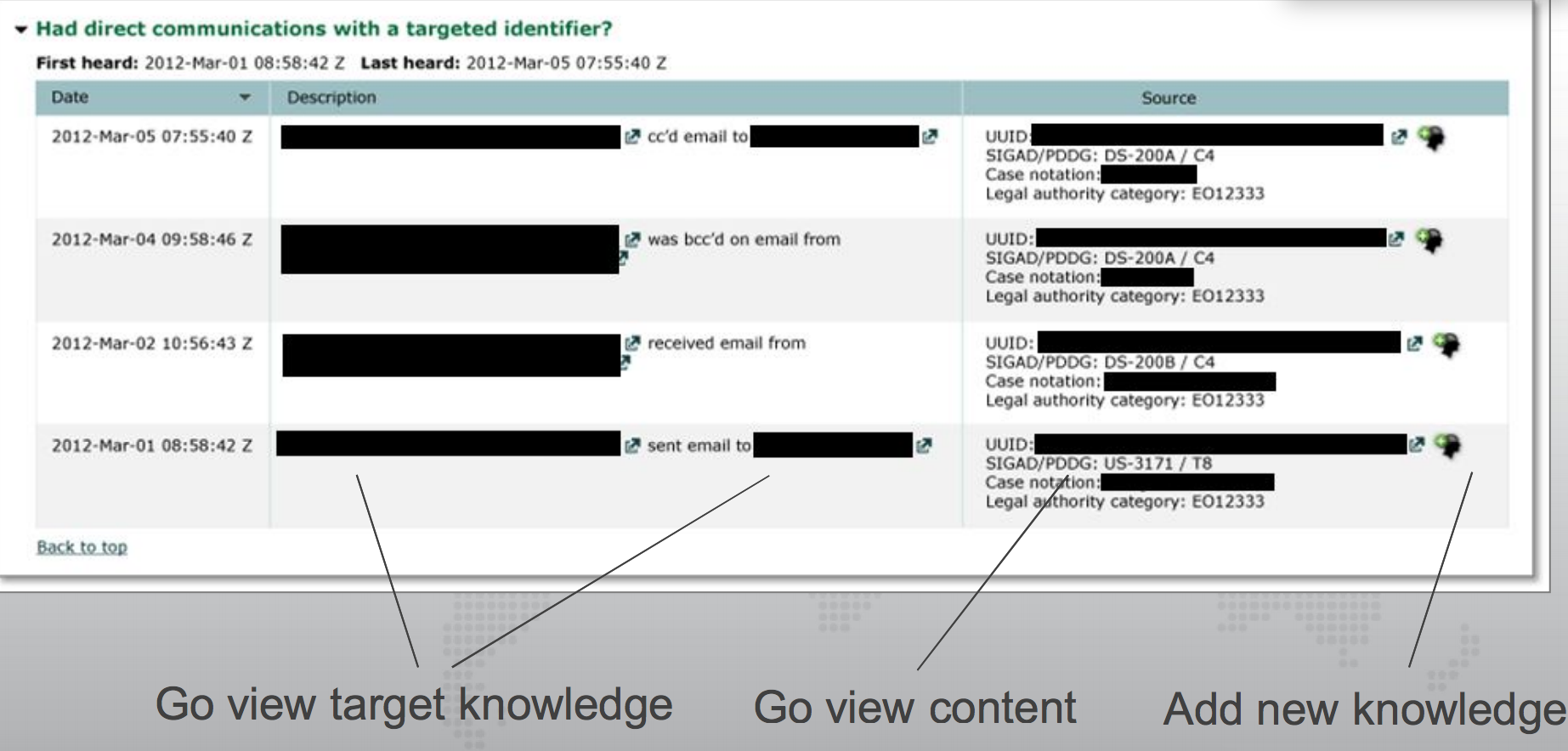

Finally, a Snowden document dating to March 2012 (when NSA was still setting up back door searches) shows that an NSA triage program would first walk users through methods to prioritize communications based off metadata, then have links to access the content directly.

At the time, the sole authority listed was EO 12333, but as noted, this is precisely when they were implementing back door searches on 702 content.

None of this is all that surprising (but hey! Yay me for understanding precisely where back door searches came from three years ago).

But it suggests as we talk about “back door searches,” what we’re really talking about — at least when looking at access programs like the one above — is automatic notice that back door content exists, where content is just a click away.