[NB: Check the byline, thanks! UPDATES at bottom of post. /~Rayne]

I’ve previously looked at example Articles of Impeachment against Trump in these posts:

History’s Rhyme: Nixon’s Articles of Impeachment — focus on obstruction of justice

History’s Rhyme, Part 2: ‘Abuse of Power’ Sounds So Familiar

I’ll return to do Part 2a to address more abuses of power in the near future. I’m still working on Articles 3 and more related to violations of treaties and foreign policy failures, as well as human rights violations.

This post is one that I didn’t foresee needing. Where the previous posts in this series have direct parallels to the Articles of Impeachment against former president Richard Nixon, this post is about the sequence of events leading to Nixon’s eventual resignation in 1974.

What follows is an abbreviated timeline including what I think were the biggest benchmarks between the beginning of Nixon’s first term in office and his resignation. If I miss something you believe was instrumental in his exit, let me know in comments.

I wanted to look from a 50,000 foot level at the amount of time it took for Nixon to leave office from the beginning of investigations into the Watergate break-in, and particular actions on the part of investigators and Congress as well as Nixon and some of the co-conspirators. I’ll offer observations after the timeline.

Keep in mind as you read this that impeachment and removal are spelled out in the Constitution:

Article I, Section 2, subsection 5:

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Article I, Section 3, subsection 6:

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

Article I, Section 3, subsection 7:

Judgment in Cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

Article I, Section 4:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Article III, Section 2, subsection 3:

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

~ ~ ~

Timeline of Richard M. Nixon’s terms in office including impeachment effort

20-JAN-1969 — Nixon inaugurated and installed in office.

18-MAR-1969 — Unauthorized by Congress, secret bombing of Cambodia under ‘Operation Menu‘ begins.

09-MAY-1969 — NYT revealed secret bombing based on information leaked by an administration source. Nixon demanded the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) find the source of the leak; then National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger‘s NSC aide Morton Halperin was illegally wiretapped for 21 months.

XX-OCT-1969 — Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo photocopy what would become known as the ‘Pentagon Papers‘ — compiled study of the Vietnam War commissioned in 1967 by then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

~ ~ ~

26-MAY-1970 — Secret bombing of Cambodia under Operation Menu ended.

~ ~ ~

XX-FEB-1971 — Ellberg discussed the Pentagon Papers with NYT reporter Neil Sheehan, turning over some of the materials to Sheehan.

XX-FEB-1971 — Illegal wiretap of NSC aide Halperin ended.

13-JUN-1971 — NYT began publishing portions of the Pentagon Papers

20-JUN-1971 — Senator Mike Gravel entered thousands of pages of the Pentagon Papers into Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds’ record to assure public debate.

~ ~ ~

17-JUN-1972 — Five “plumbers” were caught breaking into Democratic Party headquarters in Watergate; these burglars include a GOP security aide.

20-JUN-1972 — Based on a tip from anonymous source referred to as ‘Deep Throat,’ Washington Post reported that one of the burglars had Howard Hunt’s name in an address book as well as checks signed by Hunt in their possession. Deep Throat also said Hunt was affiliated with Charles Colson, Nixon’s Special Counsel.

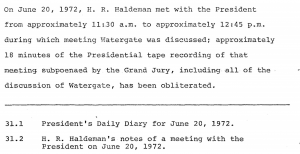

20-JUN-1972 — Recordings made in the Oval Office this day eventually contain erasures including an 18-1/2 minute gap. Some of the material recorded included a conversation between Nixon and White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman.

23-JUN-1972 — Nearly a week after the burglary at DNC offices, Nixon and Haldeman were recorded discussing how to stop the investigation into the break-in. Nixon agreed upon Haldeman’s suggestion that Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director Richard Helms and Deputy Director Vernon A. Walters should contact FBI’s Acting Director L. Patrick Gray and ask the FBI to stand down on the investigation, calling it a matter of “national security.” This conversation would become known as the “Smoking Gun” tape. [UPDATE-2]

01-AUG-1972 — Washington Post reported one of the Watergate burglars had a $25,000 cashier’s check in their bank account.

15-SEP-1972 — G. Gordon Liddy, Howard Hunt, and the five Watergate burglars — the first Watergate Seven — were indicted by a federal grand jury.

29-SEP-1972 — Washington Post reported that former Attorney General John Mitchell used a secret GOP slush fund to pay for opposition research including intelligence on the Democratic Party.

07-NOV-1972 — Nixon reelected in landslide. The race had been substantively shaped by dirty tricks conducted by Nixon’s aides.

~ ~ ~

08-JAN-1973 — The first Watergate Seven are tried by Judge John Sirica.

30-JAN-1973 — G. Gordon Liddy and James McCord, former Nixon staffers, were convicted of conspiracy, burglary, and wiretapping related to the break-in of DNC offices in Watergate.

07-FEB-1973 — Senate Watergate Committee formed by 93rd Congress under S.Res. 60, to investigate the break-in at DNC, “all other illegal, improper, or unethical conduct occurring during the presidential election of 1972, including political espionage and campaign finance practices,” and subsequent cover-up.

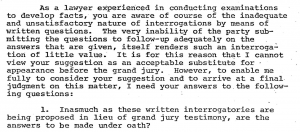

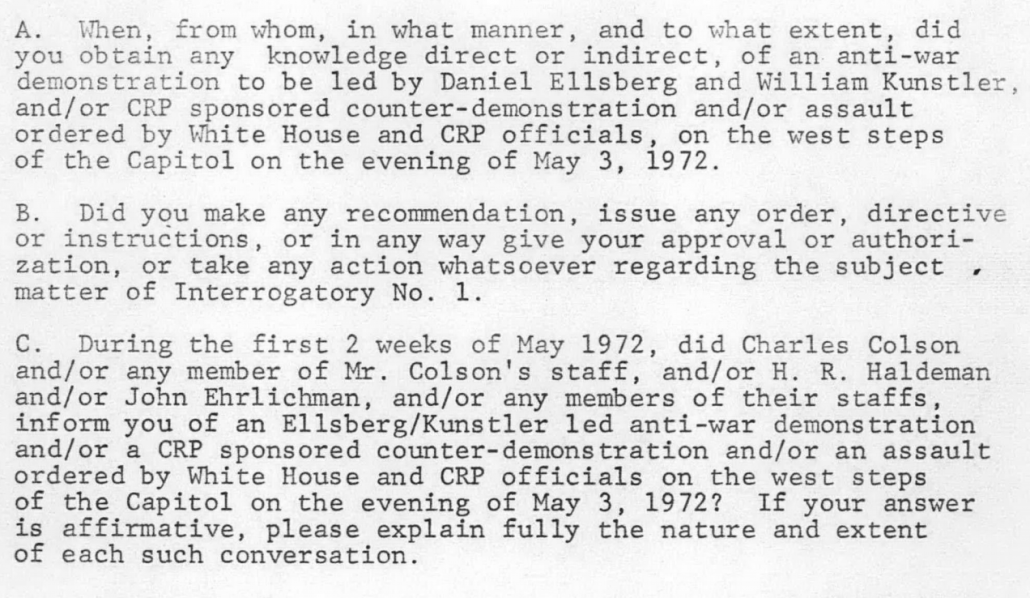

21-MAR-1973 — White House counsel John Dean, who’d been tasked with tracking and updating Nixon on the progress of the Watergate investigation, discussed the hush money payments to the team of burglars calling the mounting obstruction of justice a “cancer on the presidency.”

17-APR-1973 — Dean informs Nixon that he had been cooperating with the U.S. Attorneys investigating the Watergate break-in. Nixon is informed the same day by U.S. Attorneys that White House counsel Dean, Chief of Staff Haldeman, and aide Ehrlichman were involved in the cover-up.

30-APR-1973 — Nixon fires Dean; he had asked for the resignations of Haldeman and Ehrlichman as well as Attorney General Richard Kleindienst who had been friends with Haldeman and Ehrlichman.

17-MAY-1973 — Senate Watergate Committee hearings began.

19-MAY-1973 — Special prosecutor Archibald Cox appointed to begin investigation into presidential impropriety.

25-JUN-1973 — Dean testified before the Watergate Committee. He had been granted limited immunity and eventually pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice, for which he eventually served several months in prison. [UPDATE-1]

13-JUL-1973 — White House aide Alexander Butterfield testified before Congress that Nixon secretly taped phone calls and conversations in Oval Office.

18-JUL-1973 — Nixon had recording system disconnected in White House.

23-JUL-1973 — Nixon refused to turn over presidential tapes to Senate Watergate Committee or to special prosecutor.

20-OCT-1973 — Nixon fired Special Counsel Archibald Cox and replaced him with Leon Jaworski (Saturday Night Massacre).

23-OCT-1973 — In the furor of the public’s displeasure about the firing of Cox, Nixon agrees to release some of the Oval Office tapes.

17-NOV-1973 — Nixon said during a Q&A on TV, “Well, I’m not a crook.”

21-NOV-1973 — A number of erasures amounting to 18-1/2 minutes were discovered in released Oval Office tapes. Nixon’s personal secretary Rose Mary Woods claimed responsibility for the erasures, blaming the loss on accidentally depressing a pedal on a transcription device while answering the phone.

~ ~ ~

01-MAR-1974 — The second Watergate Seven, all advisors and aides to Nixon, were indicted by a grand jury; Nixon was named an unindicted co-conspirator.

18-APR-1974 — Special prosecutor Jaworski subpoenaed Nixon for his presidential tapes.

09-MAY-1974 — House Judiciary Committee launched impeachment hearings.

24-JUL-1974 — Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn tapes over to investigators.

27-JUL-1974 — Over the course of three days, the House Judiciary passed three of five articles of impeachment which include charges against Nixon of obstruction of justice and other unlawful acts, abuse of power, and failure to uphold his oath of office.

XX-AUG-1974 — A White House tape from 23-JUN-1972 was released; referred to as the “Smoking Gun” tape, Nixon and co-conspirator Haldeman are heard plotting obstruction of justice.

07-AUG-1974 — A few key GOP Senators told Nixon there are enough votes in the Senate to convict and remove him from office.

08-AUG-1974 — Nixon gave his resignation speech to the American public over national broadcast television.

09-AUG-1974 — Nixon resigned.

~ ~ ~

I was a tweenager at the time the Watergate Committee hearings commenced. I remember watching them on black-and-white television and thinking them the most boring events in the world at the time. There was nothing else on to watch; it didn’t help that it was during summer vacation in remote northern Michigan and there was only one television station.

But now I wish I’d paid attention to those suited old white dudes droning on in the Senate and in the House. I might have realized much sooner there is something very different about the way the Trump-Russia investigation has unfolded compared to the Watergate investigation.

Note very carefully when the first Congressional hearing was held in May of 1973.

It took roughly 15 months to remove the president from the beginning of these hearings until Nixon was persuaded to resign instead of being forced out by conviction and removal by the Senate.

The first hearing was convened by the Senate Watergate Committee — not the House Judiciary, and without the additional implicit constitutional power conferred upon a House impeachment inquiry.

Why is the Senate under Mitch McConnell’s leadership utterly supine in the face of attacks on our election infrastructure by a hostile nation-state?

Why has McConnell done absolutely nothing to further the investigation into the attacks nor into the possible obstruction of justice the Special Counsel’s report outlined, from which the Special Counsel could not exonerate Trump?

Why is McConnell doing nothing at all except waving through a train of poorly-qualified and often compromised presidential nominees for various posts including judgeships with lifetime appointments?

Why is McConnell proving the value of John Dingell’s recommendation that the Senate be abolished since McConnell has refused to submit at least a hundred of the House’s passed legislation for a Senate vote — including a bill which is intended to bolster election security?

By the time the House Judiciary Committee began its impeachment hearings almost exactly one year after the Senate Watergate Committee hearings had begun, the House did not have much to do. Only three months transpired between the launch of the House Judiciary Committee hearings and Nixon’s resignation.

Only a little over two months passed between the House Judiciary beginning impeachment proceedings and the passage of the three Articles of Impeachment which encouraged Nixon’s departure.

For all the complaining about House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s leadership with regard to investigations into Trump-Russia and subsequent impeachment, the press has not held McConnell to account for his failure of leadership.

Of course McConnell is a Republican and belongs to the same party as Trump; the Senate is led by the GOP now and both houses of Congress were majority Democratic Party in 1973-1974. But this is a nation of laws; a Republican-appointed, Republican-approved Special Counsel conducted an investigation which did not lead to the exoneration of the president. The GOP-majority Senate helmed by McConnell is just as capable of conducting an investigation into alleged White House misdeeds, could form a dedicated investigatory committee just as the 93rd Congress did back in 1973.

But no. Not Mitch McConnell, who has been compromised in several ways that we know of and has himself obstructed both the investigation into Trump-Russia and prevented the public from knowing they were under attack.

What else do you see in this timeline which is relevant to today’s investigations into Trump-Russia, Trump’s obstruction of justice, his abuses of power, and other failures to uphold the oath of office?

~ ~ ~

While House Committees have already begun hearings into Trump administration activities as part of their oversight responsibilities, formal impeachment proceedings have not yet begun. Following are the anticipated next steps which should happen sooner rather than later; compare them to the Nixon timeline:

- One of two paths open the impeachment process: 1) A resolution to impeach a civil officer may be referred to the House Judiciary Committee, or 2) a resolution to authorize an investigation as to whether grounds exist for impeachment is referred to the House Committee on Rules; the resolution is then referred to the House Judiciary Committee.

- The House Judiciary drafts and approves a bill for House consideration and approval outlining the authorization to investigate fully grounds for impeachment, the powers the investigative committee may use in the course of its investigation, and the budget for such an investigation.

- As specified in the authorizing bill, the House Judiciary or other House committee, perhaps even select or special for the purpose of the investigation alone, conducts its investigation and reports as required by its authorization or House rules.

- Assuming adequate grounds for impeachment have been found, the House Judiciary drafts and approves articles of impeachment outlining the “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” against the civil officer in question.

- The entire House votes to impeach the civil officer based on the articles approved by the House Judiciary; it votes on a resolution to inform the Senate of the impeachment.

- The Senate, being responsible for trial and possible conviction, should take up a trial at this point with the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice presiding. What’s not clear is if the Senate can refuse to begin a trial once the House has impeached; once the Senate begins, the steps it takes are governed by the Rules of Procedure and Practice in the Senate when Sitting on Impeachment Trials.

This last bullet point is no small hiccup.

You can learn more about Congress’s power to impeach and remove civil officers by reading these two Congressional Research Service papers:

Impeachment and Removal, R44260 (pdf)

Recall of Legislators and the Removal of Members of Congress from Office, RL30016 (pdf)

I note the first was prepared in 2005 during the Bush administration. I wonder who requested this paper; I also wonder who requested the second paper in early 2012.

That second paper might be a particularly worthwhile read if one were interested in how to go about removing an obstructive member of Congress or a cabinet member who has proven unsuited to their office. Imagine what could happen if enough Senators decided they needed to change things up on their side of the legislative branch.

UPDATE — 03-JUN-2019 —

Timeline items (highlighted in yellow above) have been added related to Nixon’s White House counsel due to new developments reported today:

Former White House counsel John Dean will testify before the House Judiciary Committee on June 10, committee chair Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.) said Monday. The hearing, titled “Lessons from the Mueller Report: Presidential Obstruction and Other Crimes,” will also feature former U.S. attorneys and legal experts. (via HuffPo)

John Dean will convey the import of the Special Counsel’s report since Trump’s White House counsel Don McGahn will not comply with the House Judiciary request for his appearance to testify.

UPDATE — 05-JUN-2019 —

A reader pointed out the origin of the “Smoking Gun” tape, a conversation on June 23, 1972, was not included in my timeline and has now been added (highlighted in turquoise above). The tape captured Nixon’s direct involvement in obstruction of justice less than one week after the break-in at the Democratic Party HQ in the Watergate complex. We may not have anything quite as tidy as the “Smoking Gun” produced by the Special Counsel’s investigation, but repeated efforts by Trump to shut down the Trump-Russia investigation documented by witnesses are quite damning when combined with the firing of FBI Director James Comey and the harassment and termination of FBI employees Andrew McCabe and Peter Strozk.