In early 2018, Ivan [Y]Ermakov,* one of the hackers alleged to have stolen John Podesta’s emails two years earlier, was living it up.

For his April 10 birthday that year, he went on a stunning heli-ski trip with his future co-conspirator, Vladislav Klyushin (Ermakov is on the left in this picture, Klyushin, on the right and in the Featured Image picture).

In summer 2018, they were enjoying the Sochi World Cup together, too.

Just days after this trip to Sochi, however, on July 13, 2018, Robert Mueller would indict Ermakov, along with eleven of his former GRU colleagues, for hacking the DNC, DCCC, Hillary Clinton, election vendors, and registration websites, as well as orchestrating the release of the stolen files.

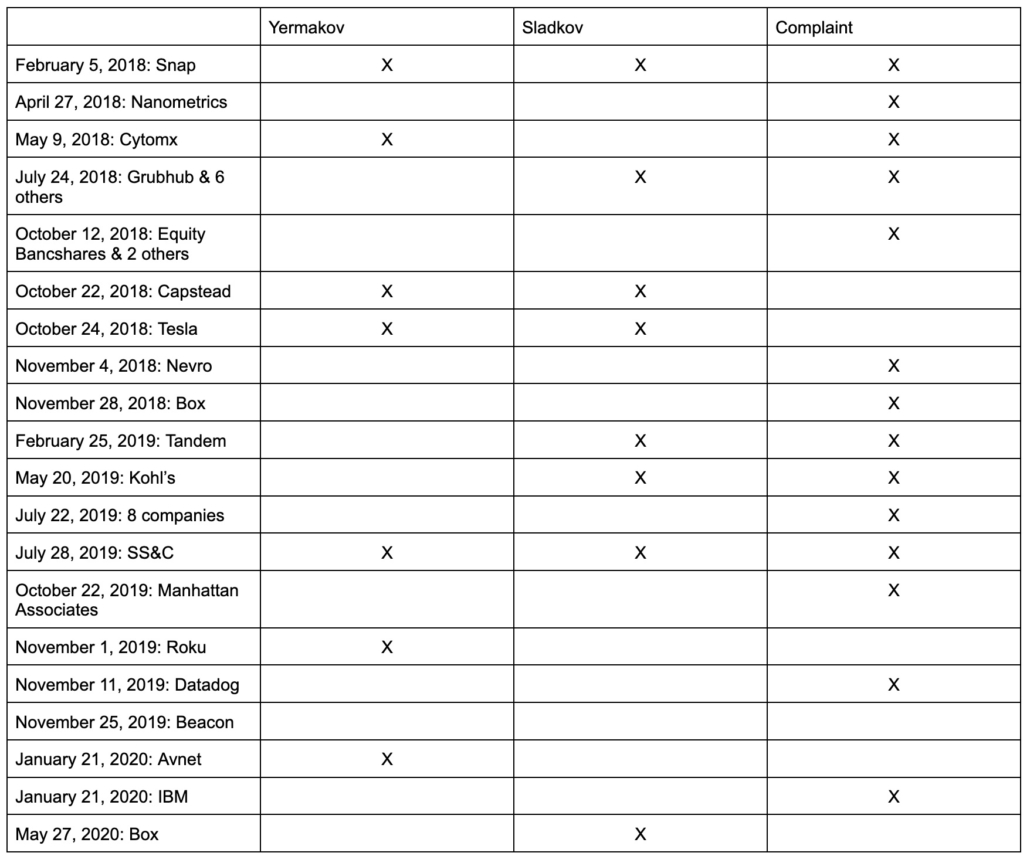

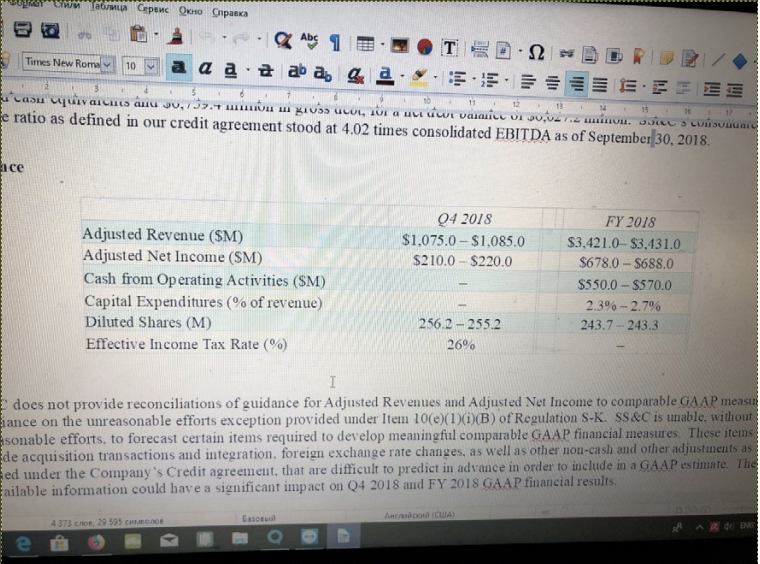

By the time of that first indictment against him — the first of three known indictments against the Russian hacker so far — Ermakov had already made one of the fatal slip-ups that would form part of the proof against Klyushin at trial, this time for a hack-and-trade scam. On May 9, 2018, Yermakov received three updates from his Apple iTunes account to the IP address 119.204.194.11. Just four minutes later, someone using that IP address downloaded an SEC filing using credentials stolen from a Donnelly Financial employee named Julie Soma. That download occurred hours before the report would be publicly filed with the SEC, one of dozens of such thefts of SEC filings that formed the basis of the hacking and securities fraud charges against the men.

So months before Mueller’s indictment alerted Ermakov that the FBI had discovered who he was and that they believed he was one of the hackers behind the 2016 hack, he had already left proof in US-based servers that would tie to him to a follow-up crime, the hack-and-insider trading conspiracy for which Klyushin was convicted in February.

Klyushin has challenged the verdict, largely based on a technical challenge to the venue of the charges in Massachusetts.

Per trial testimony, Ermakov left those tell-tale forensic tracks four months before Klyushin would first get involved in the hack-and-trade scheme, in August 2018. The scheme was doomed from the start — at least, it would be doomed if any of the identified co-conspirators traveled to a jurisdiction that would extradite to the US, as Klyushin did in March 2021.

In fact, there’s something curious about that.

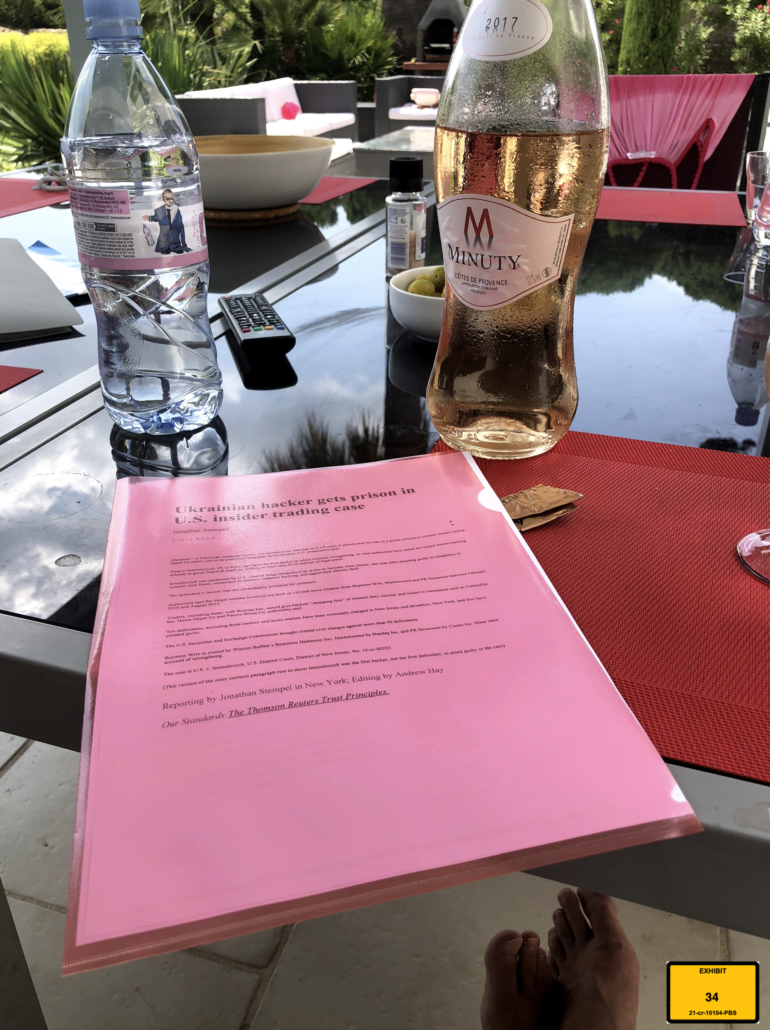

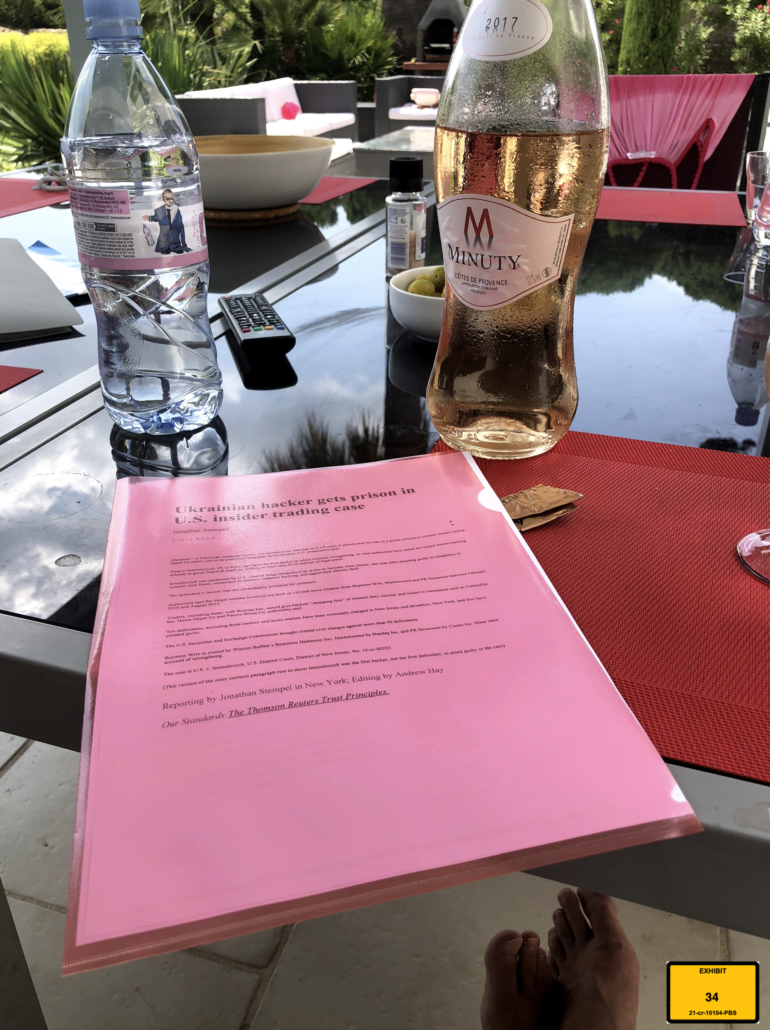

One thing submitted as evidence at trial was a picture of a May 22, 2017 Reuters article reporting the US sentence for Ukrainian hacker Vadym Iermolovych, one of ten people prosecuted for a hack-and-trade conspiracy similar to the one for which Klyushin was convicted.

According to the FBI agent who introduced the exhibit, the picture itself was taken in August 2018. Someone printed out the article and packaged it up in a plastic folder over a year after the fact. That suggests Klyushin was in discussion with a very well-connected friend about the possibility of such charges in the same month that Klyushin first got involved in the scheme.

The possibility of prosecution hung over the conspiracy from the start.

Thanks to Klyushin’s promiscuous storage of damning evidence in his iCloud account, from which many of the pictures and chats in this post were obtained by the FBI, the Klyushin case offers an unprecedented public glimpse into the effect that US indictments against nation-state hackers like Ermakov might have on one of the target’s lives. In Ermakov’s case, it didn’t stop him from hacking US targets. Indeed, it’s possible that others used the indictments to pressure Ermakov to use his hacking skills for them.

Since 2014, DOJ has been indicting nation-state hackers in what have always been assumed to be name-and-shame documents, indictments that would never lead to trial. Indeed, that’s what the two earlier indictments of Ermakov have always been assumed to be: a public accusation that would never lead to Ermakov’s imprisonment. The wisdom of indicting nation-state hackers has never been obvious. Yevgeniy Prigozhin’s exploitation of his own name-and-shame indictment has revealed the potential perils of the policy. And Russian denialists brush off the July 2018 indictment charging Ermakov and others with the election year hack (as Matt Taibbi did in his recent congressional testimony), arguing that since the indictment will never be tested at trial, it could be mere government propaganda.

At least in the case of the 2016 Russian operation, the indictment has done little to persuade denialists, who simply refuse to read about the many places where the hackers left evidence.

In a follow-up, I’ll show how DOJ proved their case against Klyushin using the same kind of evidence they used in the earlier indictments against Ermakov and his colleagues, largely metadata and content obtained from US-based and a few foreign servers. DOJ may never get a chance to prove the first two indictments against Ermakov, but using the same investigative techniques, they did prove the case against Ermakov’s co-conspirator, Klyushin.

This case, where a sealed complaint ultimately led to the trial of one co-conspirator of a hacker previously charged, also provides a glimpse of what happened after one nation-state hacker got name-and-shamed in the US.

It’s not clear from the trial record when Ermakov left the GRU or who his formal employer was before he joined Klyushin’s M-13, an information services company with ties to Putin’s office that offered, among its services, pen testing.

The FBI found a contact card for Igor Sladkov, with whom Ermakov may have started the hack-and-trade scheme at least as early as October 2017, in Ermakov’s own iCloud account, one of the only interesting pieces of evidence they found there. It was dated November 16, 2016, just over a week after Donald Trump got elected with Ermakov’s help. Sladkov — whose iCloud OpSec was just as shoddy as Klyushin’s — had a bunch of photos of Ermakov in his iCloud account, including the hacker’s passport, a 2016 picture of Ermakov sitting before an enormous plate of some animal flesh, and a picture from Ermakov’s 2018 ski trip, as well as a picture of Klyushin’s yacht that Ermakov had shared.

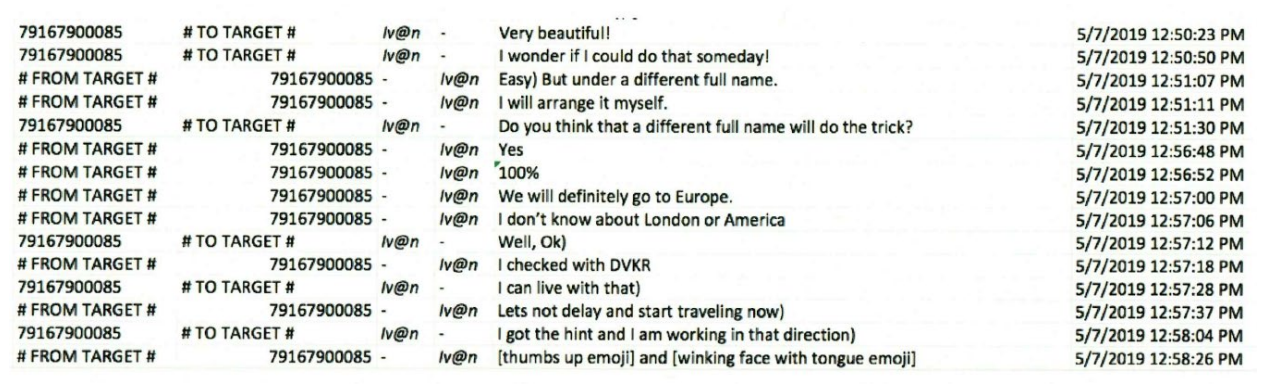

Before trial, Klyushin’s team argued that Ermakov never worked for Klyushin’s company, bolstering the claim with a chat from May 2019 in which Ermakov bitched about his job to Klyushin and a certificate from the Russian tax service claiming that [Y]Ermakov never worked at M-13.

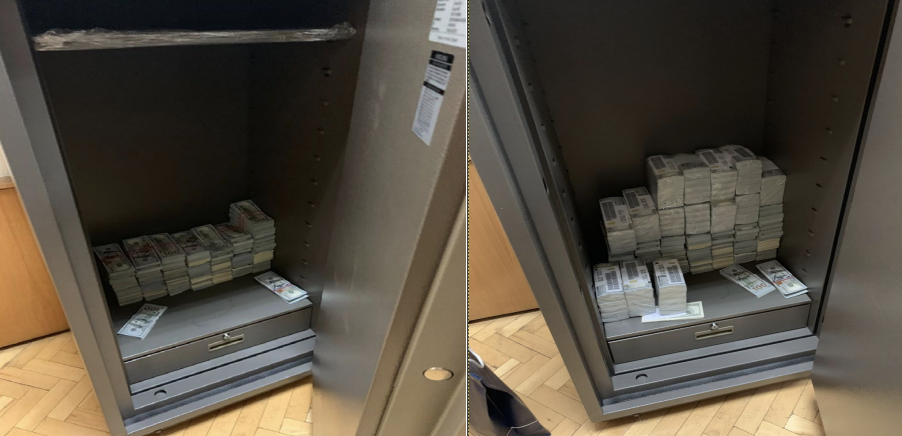

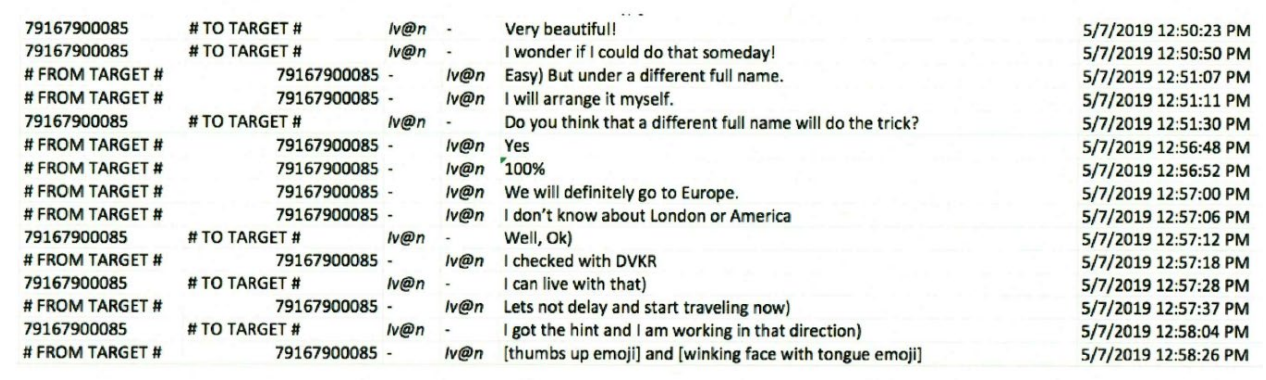

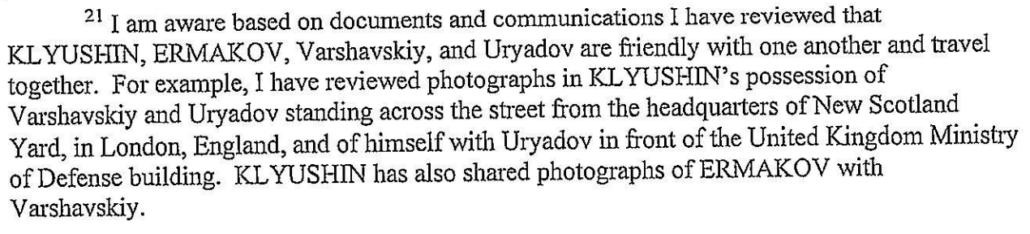

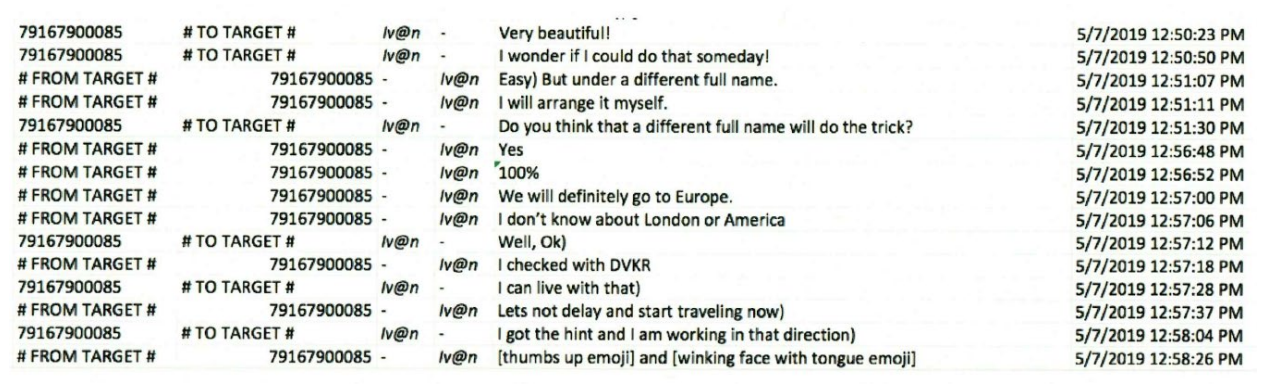

But days after that chat, per another pre-trial filing, Ermakov spoke longingly of being able to travel like Klyushin could. Klyushin responded that he would get Ermakov new identity papers so the two could travel to Europe together, but not — Klyushin conceded — London or America. Klyushin seemingly used that discussion as background to press Ermakov to get back to work, with the implication being he should get back to the hack-and-trade scheme.

That is, Ermakov appears to have included Klyushin in the hack-and-trade scheme while still working for someone else. And Klyushin seems to have used his promise to help Ermakov mitigate the risks created by those earlier indictments to pressure Ermakov to keep hacking. If that’s right, the vulnerability created by the earlier indictments gave Klyushin leverage to get Ermakov to keep hacking.

But Ermakov did eventually join M-13, at least informally. The government introduced an M-13 employee list reflecting Ermakov’s participation in specific project at trial. And they submitted a picture, from December 2019, showing Ermakov with an M-13 sticker, within days of the time when a staging server similar to the one used in the 2016 hack of the Democrats was set up.

Klyushin may have even incorporated Sladkov into M-13. The FBI found a proposal for a data analysis service, dated September 4, 2019, which M-13 would introduce on October 28, 2020, as well as encrypted communications from an M-13 chat application, in Sladkov’s iCloud account.

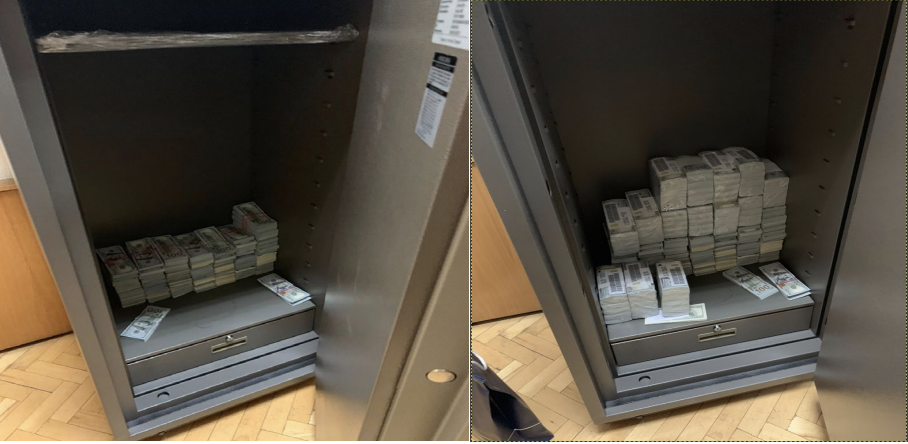

Klyushin fought hard to exclude one of the most telling pieces of evidence that the hacking scheme came to be tied to M-13 — the four Porsches that, Klyushin bragged to an investor, he had bought for himself, Ermakov, and one other co-conspirator with the proceeds of the insider trading.

But this currency — expensive gifts — seems to have been at least part of the way Erkamov was compensated for his role in the scheme.

Ermakov did not engage in any trading himself. Instead, two men in St. Petersburg, two associated with M-13 (including Klyushin himself), and three clients of M-13, profited off documents [Y]Ermakov seems to have stolen.

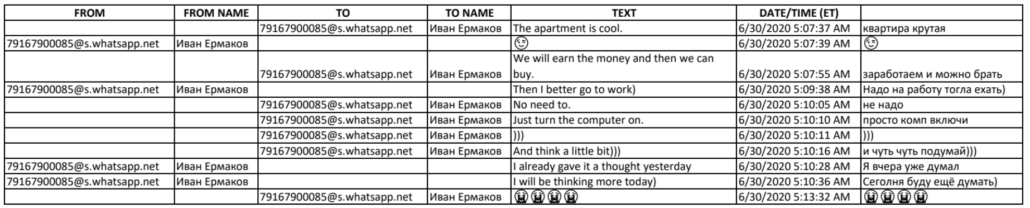

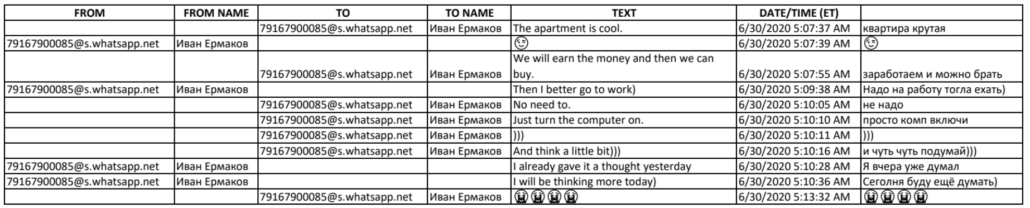

But in addition to the Porsche, on August 17, 2020, ten days before the delivery of the Porsches, Ermakov took possession of a Moscow house worth millions, the loan agreement for which Klyushin reportedly ripped up. Months earlier, Klyushin had tied paying for the house with continued hacking — which, Klyushin joked, amounted to just turning on the computer and thinking about making money.

Ermakov was effectively printing money for Klyushin, and his reward was that house.

In September 2020, the hack-and-trade scheme would be shut down for good.

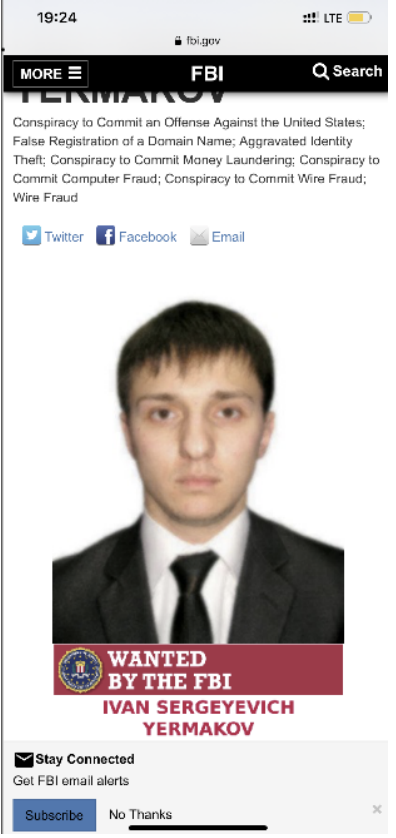

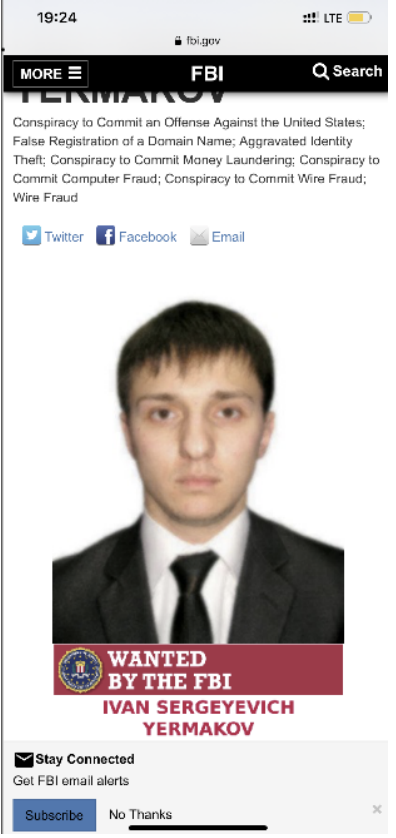

Throughout the time it was going, however, those co-conspirators knew of the indictment against Ermakov. Sladkov downloaded Ermakov’s wanted poster from the FBI website on October 5, 2018, just a day after Ermakov was charged in the 2016 hack-and-leak of anti-doping agencies while Ermakov was still a GRU officer.

And on October 4, 2020, Klyushin took a screencap of Ermakov’s wanted poster from the FBI website.

By the time Klyushin took this screencap, the victim filing agencies had finally shut down Ermakov’s access to the site, after eight months of trying. Perhaps Klyushin was contemplating what that would mean or how it had happened? According to trial evidence, DOJ didn’t identify the hack-and-trade scheme by tracking what Ermakov was doing. Rather, the investigation started when the SEC started tracking some large-scale trading by a bunch of Russians together, then asked the filing agencies if they had been hacked. At least according to the public record, the involvement of Ermakov was disclosed only after working backwards from the forensic evidence. But in October 2020, Klyushin may have considered the risks of entering into a hack-and-trade scheme with a hacker whose habits were already known within the FBI.

By then it was too late. Indeed, Ermakov had already warned his boss about his shoddy OpSec. On July 18, 2019, Kluyshin asked Ermakov and the other M-13 co-conspirator Nikolai Rumiantcev how the hack-and-trade was going. He included pictures of two of the M-13 investors. In response, Ermakov warned his boss that that kind of OpSec is the kind of thing that would land him as a defendant in a courtroom.

Q. Okay, thank you. And now can we move to 3980, please. And this date is?

A. This is July 18 of 2019.

Q. Would you begin with 3980.

A. “Vladislav Klyushin: So what did we earn today?”

Q. And then there’s an attachment?

A. Correct.

Q. And then he says what?

A. Ermakov responds: “About 350 and another 350 in the mind. Sasha the most among the rest. “Klyushin: Our comrades are wondering.”

MR. FRANK: Could we stop right there, and I realize it’s hard, Ms. Lewis, because we’re in the Excel, but could you please display Exhibits 52 and Exhibit 50.

Q. Those are the attachments, Special Agent. Have you had an opportunity to review those?

A. Yes.

Q. Who’s depicted in Exhibits 52 and 50?

A. On the left, 52 is Sergey Uryadov. On the right is Boris Varshavksiy in Exhibit 50.

MR. FRANK: I offer 52 and 50. (Exhibits 50 and 52 received in evidence.)

Q. Okay. So those are the two attachments Mr. Klyushin has just transmitted in the chat?

A. Yes.

Q. Can we go back to the chat and pick up where we left off. So Mr. Klyushin says, “What did we earn today? Our comrades are wondering.” Could you continue, please, at 3987.

A. After sending those pictures we just looked at, Ermakov replies: “Vlad, you are exposing our organization. This is bad.” Nikolai Rumiantcev: Vlad, stop sending to Threema.” Klyushin replies, “So sorry.” “Ermakov: And that’s how they get you and you end up as a defendant in a courtroom.”

Q. How does Mr. Klyushin respond?

A. Klyushin responds, “Removed. Open a chat with us already. “Ermakov: Go ahead and create. It was a bad move now. “Klyushin: Sorry. Did a dumb thing. “Rumiantcev: I suggest to recreate the chat with the deletion of attachments in Threema, or switch to ours if ready. “Klyushin: I will delete this one on my end.”

Klyushin did delete this chat. Rumiantcev left it in his iCloud account, where the FBI found it.

At the time, the men appear to have been shifting their trading discussions to the encrypted M-13 chat application found in all their iCloud accounts, finally taking measures to cover their tracks going forward, over eighteen months into the hack-and-trade conspiracy. Going forward, those working with Ermakov might not exhibit the kind of abysmal OpSec that produced abundant trial evidence against his co-conspirator. Maybe they learned their lesson, and they’ll be able to exploit Ermakov’s skill more safely going forward.

It remains to be seen whether the prosecution of Klyushin, with his ties to high even higher ranking Russians, does more than hold him accountable for millions in fraudulent trades. But that may have little effect on the life of John Podesta’s suspected hacker.

* The government has used two different transliterations for [Y]Ermakov’s last name. In 2018, they used the one that aids in pronunciation. In 2021, they used the direct transliteration from the Cyrillic. Because evidence submitted at Klyushin’s trial uses the initials “IE” to refer to Ermakov, I’ll adopt that spelling here.