As I laid out a few weeks ago, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.

Recent developments in both the investigations into Carter Page and Paul Manafort have focused attention on a question I’ve been wondering about for some time: how any investigation will prove whether suspected Russian assets on the Trump campaign were ever with the campaign or really got fired.

Carter Page’s alleged denial and deception that he did what a potentially disinformation-filled dossier says he did

First, consider the Carter Page FISA applications. As I’ve said repeatedly, I actually think the FBI should be held accountable for their inclusion of the September 23, 2016 Michael Isikoff article based off of Steele’s work given their credulity that that reporting wasn’t downstream from Steele, particularly their continued inclusion of it after such time as Isikoff had made it clear the report relied on Steele. To be clear — given that they include this from the start, I’m not suggesting bad faith on the part of the FBI; I’m arguing it reflects an inability to properly read journalism that gets integrated into secret affidavits (this is something almost certainly repeated in the Keith Gartenlaub case). If you’re going to use public reporting in affidavits that will never see the light of day, learn how to read journalistic sourcing, goddamnit.

The Page application defenders argue that the inclusion of Isikoff in the Page application is not big deal because it didn’t serve to corroborate the Steele dossier on which it was based. That’s generally true. Instead, Isikoff is used in a section titled, “Page’s Denial of Cooperation with the Russian Government to Influence the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” The section serves, I think, to show that Page was engaging in clandestine support of a Russian effort to undermine the election. The application claims FBI had probable cause that Page was an agent of a foreign power because he met clause E, someone who aids, abets, or conspires with someone engaging in clandestine activities, including sabotaging the election.

(A) knowingly engages in clandestine intelligence gathering activities for or on behalf of a foreign power, which activities involve or may involve a violation of the criminal statutes of the United States;

(B) pursuant to the direction of an intelligence service or network of a foreign power, knowingly engages in any other clandestine intelligence activities for or on behalf of such foreign power, which activities involve or are about to involve a violation of the criminal statutes of the United States;

(C) knowingly engages in sabotage or international terrorism, or activities that are in preparation therefor, for or on behalf of a foreign power;

[snip]

(E) knowingly aids or abets any person in the conduct of activities described in subparagraph (A), (B), or (C) or knowingly conspires with any person to engage in activities described in subparagraph (A), (B), or (C).

To prove this is all clandestine, the FBI needs to show Page and his alleged co-conspirators were hiding it, in spite of the public reporting on it.

The FBI cites this Josh Rogin interview with Page as well as a letter he sent to Jim Comey, to show that Page was denying that he was conspiring with Russians.

“All of these accusations are just complete garbage,” Page said about attacks on him by top officials in the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and unnamed intelligence officials, who have suggested that on a July trip to Moscow, Page met with “highly-sanctioned individuals” and perhaps even discussed an unholy alliance between the Trump campaign and the Russian government.

As far as Page’s denials, he was specifically denying meeting with Igor Sechin and Igor Diveykin. He was definitely downplaying the likelihood that he got the invitation to Moscow because he was associated with Trump’s campaign, and he was not fulsome about having a quick exchange with other high ranking Russians.

But to this day, there is no evidence that Page did meet with Sechin and Diveykin (in the Schiff memo, he points to Page’s dodges about meeting other Russians as proof but it’s not). So citing Page’s denials to Rogin and Comey that he had had these meetings worked a lot like Saddam’s denials leading up to the Iraq War. Sometimes, when someone denies something, it’s true, and not proof of deception.

A similar structure appears to be repeated when what appears to be the section describing ongoing intelligence collection, starting with the third application (see PDF 340-1) excerpts a letter Page wrote in February 2017 attacking Hillary for “false evidence” that he met with Sechin and Diyevkin; as batshit as the letter sounds, as far as we know that specific claim is not true, and therefore this attack should only be treated as deception and denial if FBI has corroboration for other claims he denies here.

In other words, because the specific claims in the Steele dossier were the form of the accusations against Page, rather than the years-long effort the Russians made to recruit him, his willingness to play along, his interest in cuddling up to Russia, and his potential involvement in ensuring that Trump’s policy would be more pro-Russian than it otherwise might, Page’s specific denials of being an agent of Russia may well have been true even if in fact he was or at least reasonably looked like one based off other facts.

But was the Trump campaign deceiving about his departure from the campaign?

The applications don’t just show Page denying (correctly, as far as we know) that he met with Sechin and Diveykin. They also show great interest in the terms of his departure from the Trump campaign. Here’s part of what the application says about the Isikoff article:

Based on statements in the September 23rd News Article, as well as in other articles published by identified news organizations, Candidate #1’s campaign repeatedly made public statements in an attempt to distance Candidate #1 from Page. For example, the September 23rd News Article noted that Page’s precise role in Candidate #1’s campaign is unclear. According to the article, a spokesperson for Candidate #1’s campaign called Page an “informal foreign advisor” who” does not speak for [Candidate #1] or the campaign.” In addition, another spokesperson for Candidate #1’s campaign said that Page “has no role” and added “[w]e are not aware of his activities, past or present.” However, the article stated that the campaign spokesperson did not respond when asked why Candidate #1 had previously described Page as an advisor. In addition, on or about September 25, 2016, an identified news organization published an article that was based primarily on an interview with Candidate #1’s then campaign manager. During the interview, the campaign manager stated, “[Page is] not part of the campaign I’m running.” The campaign manager added that Page has not been part of Candidate #1’s national security or foreign policy briefings since he/she became campaign manager. In response to a question to a question from the interviewer regarding reports that Page was meeting with Russian officials to essentially attempt to conduct diplomatic negotiations with the Russian Government, the campaign manager responded, “If [Page is] doing that, he’s certainly not doing it with the permission or knowledge of the campaign . . . “

That passage is followed by three lines redacted under FOIA’s “techniques and procedures” (7E) and “enforcement proceedings” (7A) exemptions.

Again, this section seems dedicated to proving that Page and his conspirators are attempting to operate clandestinely — that they’re denying this ongoing operation. And the FBI treats Page’s and the campaign’s denials of any association as proof of deception.

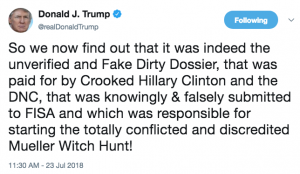

To this day, of course, President Trump considers the Page FISA to be an investigation into his campaign.

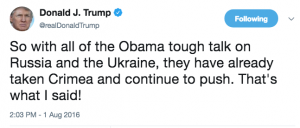

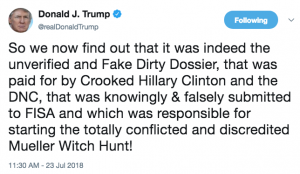

Sure, the continued conflation of the Page FISA with his campaign serves a sustained strategy to confuse his base and discredit the investigation. But by willingly conflating the two, Trump only adds to the basis for which FBI might treat the conflicting admissions and denials of Page’s past and ongoing role in the campaign in fall 2016 as part of an effort to deceive.

Which is to say that while Page’s denials of meeting with Igor Sechin might be bogus analysis, the competing claims from the campaign — while they were likely at least partly incompetent efforts to limit damage during a campaign — might (especially as they persist) more justifiably be taken as proof of deception.

Steve Bannon got picked up on Page’s wiretaps in January 2017

All the more so given that Steve Bannon reached out to Page — via communication channels that were almost surely wiretapped — in early 2017 to prevent him from publicly appearing and reminding of his role on the campaign. As Page explained in his testimony to HPSCI:

MR. SCHIFF: Have you had any interaction with Steve Bannon?

MR. PAGE: We — we had a brief conversation in January, and we shared some text messages. That’s about it.

MR. SCHIFF: January of this year?

MR. PAGE: Yes.

MR. SCHIFF: What was the nature of your text message exchange?

MR. PAGE: It was — he had heard I was going to be on I believe it was an MSNBC event. And he just said it’s probably not a good idea. So —

MR. SCHIFF: And he heard this from?

MR. PAGE: I am not sure, but —

MR. SCHIFF: So he was telling you not to go on MSNBC?

MR. PAGE: Yes.

MR. SCHIFF: And he texted this to you?

MR. PAGE: He called me. It was right when I was — it was in mid-January, so —

MR. SCHIFF: And how did he have your number?

MR. PAGE: Well, I mean, I think there is the campaign had my number. He probably got it from the campaign, if I had to guess. I don’t know.

MR. SCHIFF: And did Mr. Bannon tell you why he didn’t want you to go on MSNBC?

MR. PAGE: No. But it turns out, I mean, I saw eventually the same day and in the same hour slot in the “Meet the Press” daily, it was Vice President Pence. And this is kind of a week after the dodgy dossier was fully released. And so I can understand, you know, given reality, why it might not be a good idea when he heard, probably from the producer — somehow the word got back via the producers that I would be on there, so —

MR. SCHIFF: I am not sure that I follow that, but in any event, apart from your speculating about it, what did he communicate as to why he thought you should not go on MSNBC?

MR. PAGE: I can’t recall the specifics.

MR. SCHIFF: Did he tell you he thought it would be hurtful to the President?

MR. PAGE: Not specifically, although there was a — I had received — we had some — letter exchanges perviously, kind of sharing — between Jones Day and myself, just saying — I forget the exact terminology, but — you know, the overall message was: Don’t give the wrong impression. Or my interpretation of the message was: Don’t give the wrong impression that you’re part of the administration or the Trump campaign.

And my response to that was, of course, I’m not. The only reason I ever talked to the media is to try to clear up this massive mess which has been created about my name.

[snip]

MR. SCHIFF: So, when Mr. Bannon called you to ask you not to go on, did he make any reference to the correspondence from the campaign?

MR. PAGE: I can’t recall. Again, I had just gotten off a 14-hour flight from Abu Dhabi.

MR. SCHIFF: He just made it clear he didn’t want you to do the interview?

MR. PAGE: That’s all I recall, yeah.

MR. SCHIFF: And what did you tell him?

MR. PAGE: I told him: I won’t do it. That’s fine. No big deal.

In the wake of the release of the Steele dossier, Trump’s top political advisor Steve Bannon (who, we now know, was in the loop on some discussions of a back channel to Russia) called up Carter Page on a wiretapped phone and told him not to go on MSNBC to try to rebut the Steele dossier.

I can get why that’d be sound judgment, from a political standpoint. But the attempt to quash a Page appearance and/or present any link to Pence during a period when he was pushing back about Mike Flynn and when Bannon was setting up back channels with Russians sure seems like an attempt to dissociate from Page as the visible symbol of conspiring with Russia all while continuing that conspiracy.

Speaking of Paul Manafort’s many conspiracies

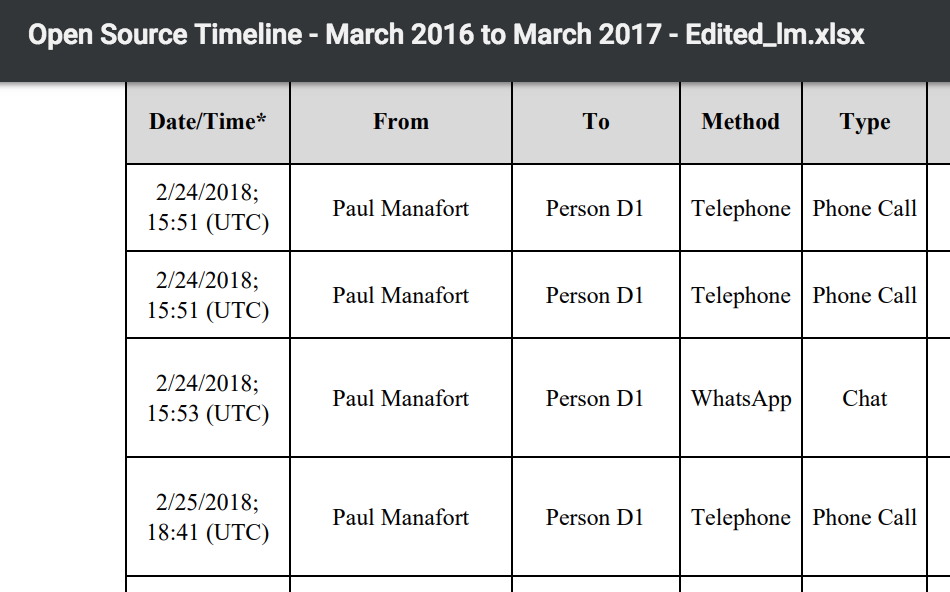

Which brings me, finally, to a filing the government submitted in Paul Manafort’s DC trial yesterday.

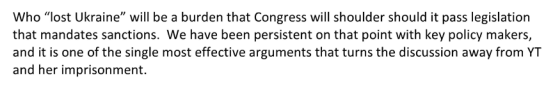

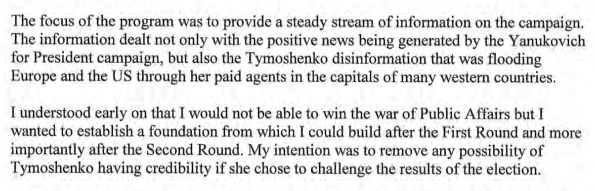

Every time people claim that neither of the Manafort indictments relate to conspiring with Russia, I point out (in part) that Manafort sought to hide his long-term tie with Viktor Yanukovych and the Russian oligarchs paying his bills in an attempt to limit damage such associations would have to the ongoing Trump campaign. Effectively, when those ties became clear, Manafort stepped down and allegedly engaged in a conspiracy to hide those ties, all while remaining among Trump’s advisors.

In response to Manafort’s effort to preclude any mention of the Trump campaign in the DC case, the Mueller team argued they might discuss it if Manafort raises it in an attempt to impeach Rick Gates.

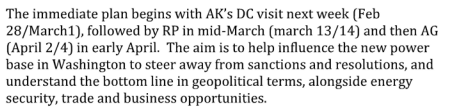

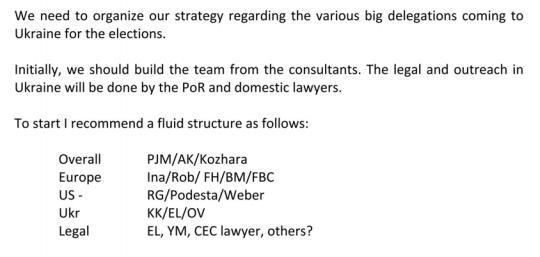

Manafort’s role in the Trump campaign, however, is relevant to the false-statement offenses charged in Counts 4 and 5 of the indictment. Indeed, Manafort’s position as chairman of the Trump campaign and his incentive to keep that position are relevant to his strong interest in distancing himself from former Ukrainian President Yanukovych, the subject of the false statements that he then reiterated to his FARA attorney to convey to the Department of Justice. In particular, the press reports described in paragraphs 26 and 27 of the indictment prompted Manafort and Gates to develop their scheme to conceal their lobbying. Dkt. 318 ¶¶ 26-27.

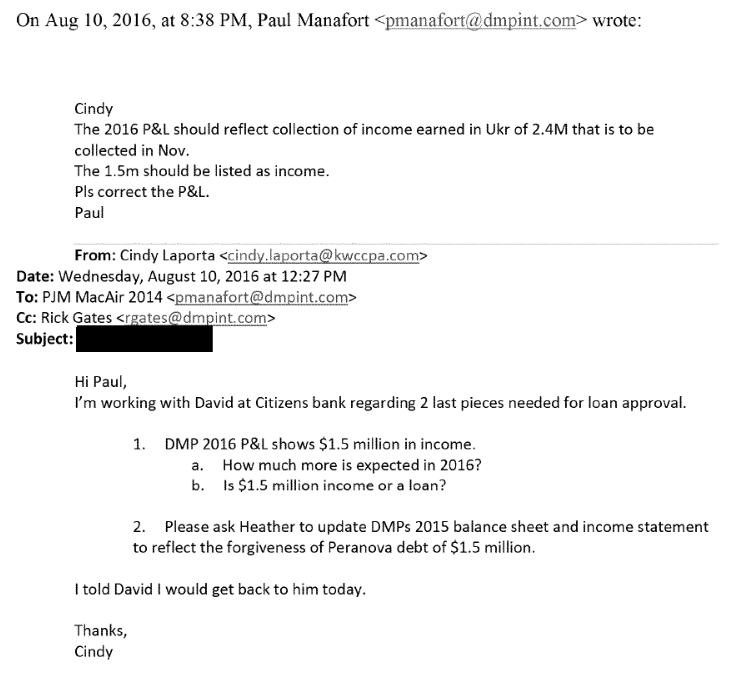

For example, on August 15, 2016, a member of the press e-mailed Manafort and copied a spokesperson for the Trump campaign to solicit a comment for a forthcoming story describing his lobbying. Gates corresponded with Manafort about this outreach and explained that he “provided” the journalist “information on background and then agreed that we would provide these answers to his questions on record.” He then proposed a series of answers to the journalist’s questions and asked Manafort to “review the below and let me know if anything else is needed,” to which Manafort replied, in part, “These answers look fine.” Gates sent a materially identical message to one of the principals of Company B approximately an hour later and “per our conversation.” The proposed answers Gates conveyed to Manafort, the press, and Company B are those excerpted in the indictment in paragraph 26.

An article by this member of the press associating Manafort with undisclosed lobbying on behalf of Ukraine was published shortly after Gates circulated the Manafort-approved false narrative to Company B and the member of the press. Manafort, Gates, and an associate of Manafort’s corresponded about how to respond to this article, including the publication of an article to “punch back” that contended that Manafort had in fact pushed President Yanukovych to join the European Union. Gates responded to the punch-back article that “[w]e need to get this out to as many places as possible. I will see if I can get it to some people,” and Manafort thanked the author by writing “I love you! Thank you.” Manafort resigned his position as chairman of the Trump campaign within days of the press article disclosing his lobbying for Ukraine.

Manafort’s role with the Trump campaign is thus relevant to his motive for undertaking the charged scheme to conceal his lobbying activities on behalf of Ukraine. Here, it would be difficult for the jury to understand why Manafort and Gates began crafting and disseminating a false story regarding their Ukrainian lobbying work nearly two years after that work ceased—but before any inquiry by the FARA Unit—without being made aware of the reason why public scrutiny of Manafort’s work intensified in mid-2016. Nor would Manafort’s motives for continuing to convey that false information to the FARA Unit make sense: having disseminated a false narrative to the press while his position on the Trump campaign was in peril, Manafort either had to admit these falsehoods publicly or continue telling the lie. [my emphasis]

Finally, Mueller is making this argument. The reason Manafort went to significant lengths in 2016 to avoid registering for all this Ukraine work, Mueller has finally argued, is because of his actions to deny the ties in an effort to remain on the Trump campaign and his effort to limit fallout afterwards.

This argument, of course, is unrelated to the competing stories that Trump told about why he fired Manafort (or whether, for example, Roger Stone was formally affiliated with the campaign during the period when he was reaching out to WikiLeaks and Guccifer 2.0). But since at least fall 2016 the FBI has been documenting efforts to lie about Trump’s willing ties to a bunch of people with close ties to Russians helping to steal the election and/or set up Trump as a Russian patsy.

And while the evidence that Page was lying when denying the specifics about the accusations against him in the dossier remains weak (at least as far as the unredacted sections are concerned), the evidence that the campaign has been involved in denial and deception since they got rid of first Manafort and then Page is not.

Carter Page’s incoherent ramblings may not actually be denial and deception. But Donald Trump’s sure look to be.

The criminal information provided far more detail about something we had only seen snippets of in the Alex Van der Zwaan plea: Manafort’s use of Skadden Arps to whitewash Yanukovych’s prosecution of Yulia Tymoshenko.

The criminal information provided far more detail about something we had only seen snippets of in the Alex Van der Zwaan plea: Manafort’s use of Skadden Arps to whitewash Yanukovych’s prosecution of Yulia Tymoshenko.