The Section 215 Dragnet Started as Abusive Exigent Letter Practice Wound Down

Julian Sanchez (who, if you’re not already following, you should, @normative) just made an important observation about the Section 215 collection that collects metadata on all phone calls every day.

Julian Sanchez (who, if you’re not already following, you should, @normative) just made an important observation about the Section 215 collection that collects metadata on all phone calls every day.

Carriers keep call detail records for years. No earthly reason to demand DAILY updates just to preserve.

Thunk. The penny dropped.

In theory, no, there’s no reason to demand daily updates from the telecoms. In fact, in theory, you could always just ask the telecoms to conduct the kind of data analysis that is now being done by NSA.

But there’s a very good reason why they’re not doing it that way.

They tried. It was badly abused.

And they started moving away from that approach in March 2006, precisely when we know the Section 215 program started.

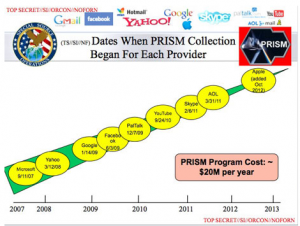

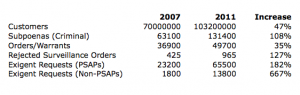

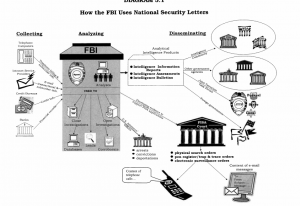

Most of what we know about the exigent letters program comes from a report DOJ’s Inspector General did in March 2007 [ed 6/16: oops–all this time I had the least damning report linked. read this one] (my posts are here, here, here, here, here, here, here). But the short version is that the NY FBI office set up an office to have representatives of the three major telecom companies come in and directly access their data with FBI Agents looking over their back. As such, it’s probably similar to what PRISM accomplishes for internet providers (except that an NSA employee rather than a telecom employee does the search), and presumably akin to whatever NSA does with the Section 215 dragnet information (which, after all, replicates the telecom databases perfectly).

The problems — that that we know about from the unclassified report (there are secret and TS/SCI versions which probably have bigger horrors) — include:

- FBI General Counsel had no apparent knowledge of 17% of the searches

- Thousands of searches never got recorded

- FBI lied to the telecoms about how urgent the information was to get the information

- FBI did an unknown number of sneak peeks into the data to see if there was something worth getting formally

Altogether, the unclassified IG Report described 26 abuses that should have been reported to then (and once again, since Chuck Hagel became Defense Secretary) inoperable Intelligence Oversight Board.

That includes the tracking of journalist call records in at least three cases (one of which I suspect is James Risen).

In short, it violated many legal principles. And that’s just the stuff that actually got recorded and showed up in an unclassified report.

The Executive spent years trying to clean up the legal mess, with four OLC opinions between November 8, 2008 and January 8, 2010 making one after another argument to justify the mess.

And just as it became clear what a godforsaken mess all this was in March 2006, they started using Section 215 to collect all call records.

The effectively created the same databases that had been abused when the FBI had telecom employees doing the work, to have NSA or FBI do the very same work as well.

In short, the reason we don’t do what Sanchez is absolutely right we should do — ask the telecoms for information as we need it — is it’s not easy enough.

What I look forward to learning, though, is how having government employees do the work that telecom employees — who at least were bound by ECPA — avoids the same kind of abusive fishing expeditions.

Update: Here’s a description I wrote to summarize this 3 years ago.

This IG Report was the third DOJ’s Inspector General, Glenn Fine, has done on the FBI’s use of National Security Letters and “exigent letters,” though this is the first to focus almost exclusively on exigent letters. In 2003, the FBI installed representatives of AT&T and (later) Verizon and MCI onsite, with computers hooked up to their respective companies’ databases. Rather than using a subpoena or a National Security Letter to get phone records from them (both of which would have required a higher level of review), the FBI basically gave them a boilerplate letters saying it was an emergency (thus the “exigent”) and could they please give the FBI the phone data; the FBI promised grand jury subpoenas to follow. Only, in many cases, these weren’t emergencies, they never sent the grand jury subpoenas, and many weren’t even associated with investigations into international terrorism. In other words, FBI massively abused this system to get phone data without necessary oversight. Fine has been pressing FBI to either establish some legal basis for getting this data or purging it from FBI databases for three years, and they have done that with some, but not all, of the data collected. But the FBI has tried about three different ways to bring this practice into conformity with legal guidelines, all unpersuasive to Fine. The OLC opinion is the most recent of these efforts.

Also, here’s a timeline.