In this post, I suggested that reports (WSJ, WaPo) that NSA collects only 20 to 30% of US phone records probably don’t account for the records collected under authorities besides Section 215.

So why did WSJ, WaPo, LAT, and NYT all report on this story at once? Why, after 8 months in which the government has taken the heat for collecting all US call records, are anonymous sources suddenly selectively leaking stories claiming they don’t get (any, the stories suggest) cell data?

There’s a tall tale the stories collectively tell that probably explains it.

None of the stories really explain why NSA didn’t start collecting cell data from the start, when, after all, it got no legal review. Nor did they note that, according to this WSJ article which a few of them cited, NSA does get cell data from AT&T and Sprint. But the stories collectively provide two explanations for why — as cell phones came to dominate US telecommunications — NSA didn’t add them to their Section 215 collection (which remember, is different from not including them in their EO 12333 collection).

First, NSA was too busy responding to crises (their 2009 phone dragnet violations and the Snowden leaks) to integrate cell data.

WSJ:

The agency’s legal orders to U.S. phone companies don’t cover most cellphone records, a gap the NSA has been trying to address for years. The effort has been repeatedly slowed by other, more pressing demands, such as responding to criticisms from the U.S. court that oversees its operations, people familiar with the matter say.

WaPo:

Compounding the challenge, the agency in 2009 struggled with compliance issues, including what a surveillance court found were “daily violations of the minimization procedures set forth in [court] orders” designed to protect Americans’ call records that “could not otherwise have been legally captured in bulk.”

As a result, the NSA’s director, Gen. Keith Alexander, ordered an “end-to-end” review of the program, during which additional compliance incidents were discovered and reported to the court. The process of uncovering problems and fixing them took months, and the same people working to address the compliance problems were the ones who would have to prepare the database to handle more records.

The NSA fell behind, the former official said.

In June, the program was revealed through a leak of a court order to Verizon by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, setting off an intense national debate over the wisdom and efficacy of bulk collection.

The same NSA personnel were also tasked to answer inquiries from congressional overseers and others about how the program and its controls worked. “At a time when you’re behind, it’s hard to catch up,” the former official said.

This claim is pretty ridiculous, given that we know (indeed, several of these reporters got selective leaks about this in October just before Keith Alexander admitted to it) NSA worked on geolocation from 2010 to 2011, which these reporters’ anonymous sources claim is the problem with cell data now. They were working on the problem, if indeed it was one.

The existence of that 2010 to 2011 pilot program also presents problems for the other explanation offered: that NSA is legally prohibited from receiving cell geolocation data.

WaPo:

Apart from the decline in land-line use, the agency has struggled to prepare its database to handle vast amounts of cellphone data, current and former officials say. For instance, cellphone records may contain geolocation data, which the NSA is not permitted to receive.

WSJ:

Moreover, the NSA has been stymied by how to remove location data—which is isn’t allowed to collect—from cellphone records collected in bulk, a U.S. official said.

[snip]

A key difficulty has been separating location data from cellphone records. NSA has an agreement with the secret Foreign Intelligence Surveillance court that it won’t collect location data from phones.

It is true that Alexander told Congress in October NSA would warn Congress and the FISC before they started collecting cell geolocation data again, but NSA still maintained it would be legal to do so.

And it is true that the intervening years since the pilot program, the Jones case presented challenges to the practice that even James Clapper admitted — back in 2012 — might force NSA to change its current practices (even while suggesting the rules were probably different for intelligence gathering as opposed to criminal investigation).

It’s also possible NSA’s delayed notice to Congress on its geolocation efforts — not even the House Judiciary Committee got notice before the Reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act in 2011 — has created problems for NSA’s collection of geolocation (and therefore, these stories claim, cell data).

Nevertheless, the record shows that DOJ and NSA believed the language of the existing Section 215 orders permitted NSA to collect cell location data at least through the end of 2011 and probably still believed it after Jones.

So that can’t be the explanation for why NSA hasn’t been collecting cell data (under Section 215, from Verizon and T-Mobile) all these years.

But the claim NSA is not permitted to collect geolocation data provides two of these stories reason to report that the purported legal prohibition on the collection of cell location has forced NSA to seek court orders for the cell data in question.

WaPo:

The government is taking steps to restore the collection — which does not include the content of conversations — closer to previous levels. The NSA is preparing to seek court orders to compel wireless companies that currently do not hand over records to the government to do so, said the current and former officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

LAT:

The NSA aims to build the technical capacity over the next few years to collect toll records from every domestic land line and cellphone call, assuming Congress extends authority for Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act after it expires in June 2015.

Once the capacity is available, the agency would seek court orders to require telecommunications companies that do not currently deliver their records to the NSA to do so.

This is the point of these stories: to prepare us for the argument, in advance of next year’s PATRIOT Act reauthorization, that Section 215 must be expanded to include cell data these reporters claim NSA doesn’t collect (they imply, under any authority) now. NSA told these reporters a story about how meager its (Section 215-based) collection is to prepare for a debate that it needs to expand authority, not curtail it.

That said, even as obviously facetious as are the claims that NSA believed it was prohibited from collecting geolocation data even as it was doing so, there have been at least two intervening events, in addition to the Jones decision, that I suspect have changed NSA’s views on cell location data. These may explain why NSA is telling this tall tale now.

First, whereas before July 19, 2013 (indeed, for the entire period when it was testing cell location data), NSA had no guidance on whether Section 215 covered cell location, in July, in the wake of Snowden’s leaks, Claire Eagan explicitly excluded Cell Location Site Identifier information from the order (though that is not the only way to get cell location).

Furthermore, this Order does not authorize the production of cell site location information (CSLI).

That is, the Executive no longer operated at the full expanse of its authority on cell geolocation, because a court bound its authority, at least for Section 215 collection.

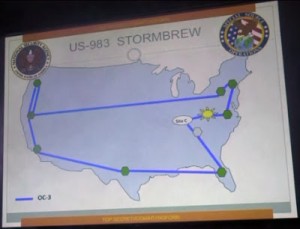

In addition, as of about two weeks ago and for the first time in 14 years, Verizon Wireless is no longer partially foreign owned. Verizon Wireless and Vodaphone announced plans to split up back in September and on January 28, the board approved the deal. The split will be final on February 21.

I suspect (this is speculation, but I will explain in a future post why my confidence on this point is very very high) that the reason NSA is telling this tall tale right now has nothing to do (as some of the stories suggested) with the fact that some of America’s key cell telecoms are partly foreign owned. Rather, I suspect any gap in cell data collection arises instead from the fact that the nation’s largest cell provider, Verizon, is no longer partly owned by a British company and therefore no longer subject to the collection agreements of GCHQ.

Say … am I really the only NSA beat writer who is wondering why it is taking ODNI so long to declassify the January 4 FISC reauthorization for the Section 215 dragnet as compared to the previous reauthorizations since the Snowden leak?