The two sides in the Michael Sussmann case have submitted their responses to motions in limine. They include:

I’m not going to do a detailed analysis of the merit of these arguments here. The filings make it clear that, unless Durham accidentally turns this into a trial about Donald Trump’s numerous back channels to Russia, the trial will focus on the meanings of “benefit” and “on behalf of.” The entire record makes it clear Sussmann understood he was representing Rodney Joffe but that he was not asking for any benefit for Joffe, and as such said he was not there on behalf of a client. Because Durham doesn’t believe that Russia was a real threat even to Donald Trump, he doesn’t believe that such a tip could benefit the country, and so sees such a tip exclusively as a political mission. As I’ll show, the YotaPhone allegation–which Durham has recently turned to as his smoking gun–in fact undermines Durham’s argument on that point (which is probably why Sussmann has no complaint about it coming in as evidence).

In general, I think Sussmann’s arguments are stronger, sometimes substantially so, but could see Judge Christopher Cooper ruling for Durham on some of them.

But I want to look at some of the new facts revealed by these filings.

Non-expert expert

As noted, Durham provided the kind of information in his response to Sussmann’s challenge to his expert that one normally provides with a first notice (here’s what Durham initially provided). Durham describes he’ll provide the basis to qualify Agent David Martin in a future disclosure (a tacit admission the resumé they had originally submitted was inadequate) which will explain,

[T]he Government intends to provide defense with a supplemental disclosure regarding his training and experience with DNS and TOR, including the following:

- As part of his cyber threat investigations, Special Agent Martin regularly analyzes network traffic, which includes DNS data;

- in furtherance of his investigations, Special Agent Martin reviews DNS data regularly, often on a daily and/or weekly basis ; and

- as an FBI Unit Chief, Special Agent Martin supervises analysts and other agents work product, which includes technical review of DNS data analysis

Which is to say Martin uses DNS data but is not as expert as a number of the possible witnesses at trial he would be suggesting were part of some grand conspiracy (note, this summary is silent on his Tor expertise, which is both a more minor part of the evidence but will be a far more contentious one at trial).

The more remarkable claim that Durham says Martin will make in rebuttal if Sussmann affirms the authenticity of the data is that, because the data was necessarily a subset of all global DNS data, it’s like it was cherry-picked, even if it was not deliberately so.

That while he cannot determine with certainty whether the data at issue was cherry-picked, manipulated, spoofed or authentic, the data was necessarily incomplete because it was a subset of all global DNS data;

Given what I’ve learned about the data in question, this judgment seems both to misunderstand the collection process and may badly misstate what an expert should be able to say. Significantly, this suggests Martin will testify as an expert without trying to replicate the effort of the various strands of research that identified the data in the first place, which is the process an expert would need to do to comment on the authenticity of the data. Not attempting to do so would only make sense if the FBI had less visibility into DNS data than the researchers in question (or if they knew replicating it would replicate the results and kill their case).

Killed the story

Several more details in the filings reveal just how far over his skis Durham is in claiming that the Democrats were the real impetus to the story (rather than, for example, April Lorenzen). Sussmann’s indictment, remember, starts with the two Alfa Bank articles published on October 31, 2016 even while he admits that Franklin Foer sources his story to Tea Leaves.

That’s true even though the indictment provides just three ways in which Sussmann was involved in the story. First and very significantly, in response to Eric Lichtblau asking (in a question that reflects past discussions about the very real hacking Russia was doing), “I see Russians are hacking away. any big news?,” Sussmann met with Lichtblau, brought Marc Elias into the loop, who in turn brought Jake Sullivan in. He undoubtedly seeded the initial story. And per his own testimony he may have pitched it to Foer and Ellen Nakashima, though Durham provides no evidence of that (unless it involves follow-up after the first Foer story).

Then, Durham describes that on October 10 — at a time when “Phil” was sending a series of DMs to the NYT about the Alfa Bank allegations and when several NYT reporters were in contact with a number of other experts, at least one of whom has never been mentioned in any Durham filings — Sussmann gave Lichtblau a nudge, but a nudge that (at least as described) not only didn’t mention the Alfa Bank allegation, but didn’t even mention Russia. He did so by forwarding an opinion piece talking about how NYT wasn’t reporting as aggressively on Trump as other outlets.

Then after Franklin Foer’s story (sourced to Tea Leaves and Jean Camp though possibly involving Sussmann) came out, Sussmann’s billing records show, he responded to other reporters’ inquiries about the story.

I have no doubt Sussmann would have loved this story to break, but Durham provides no evidence that Sussmann was the big push behind it (and the public evidence shows Tea Leaves was).

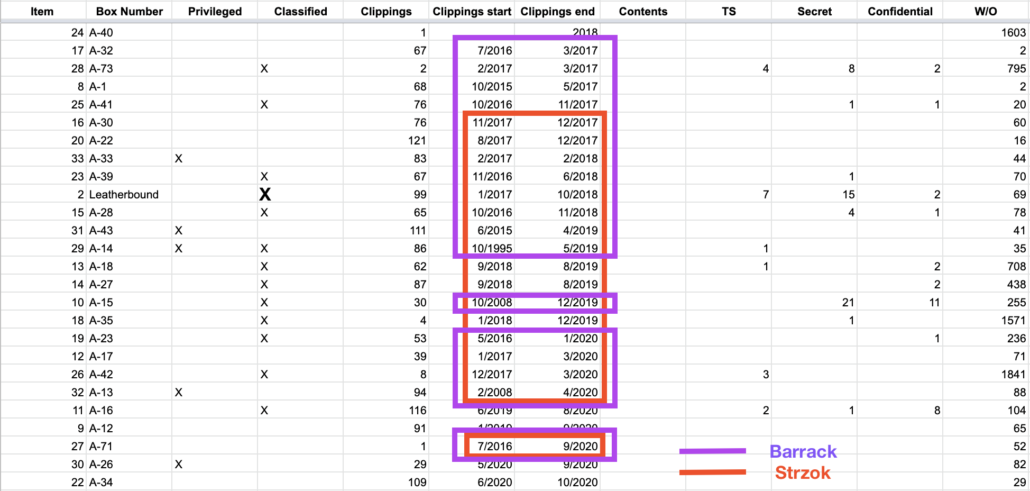

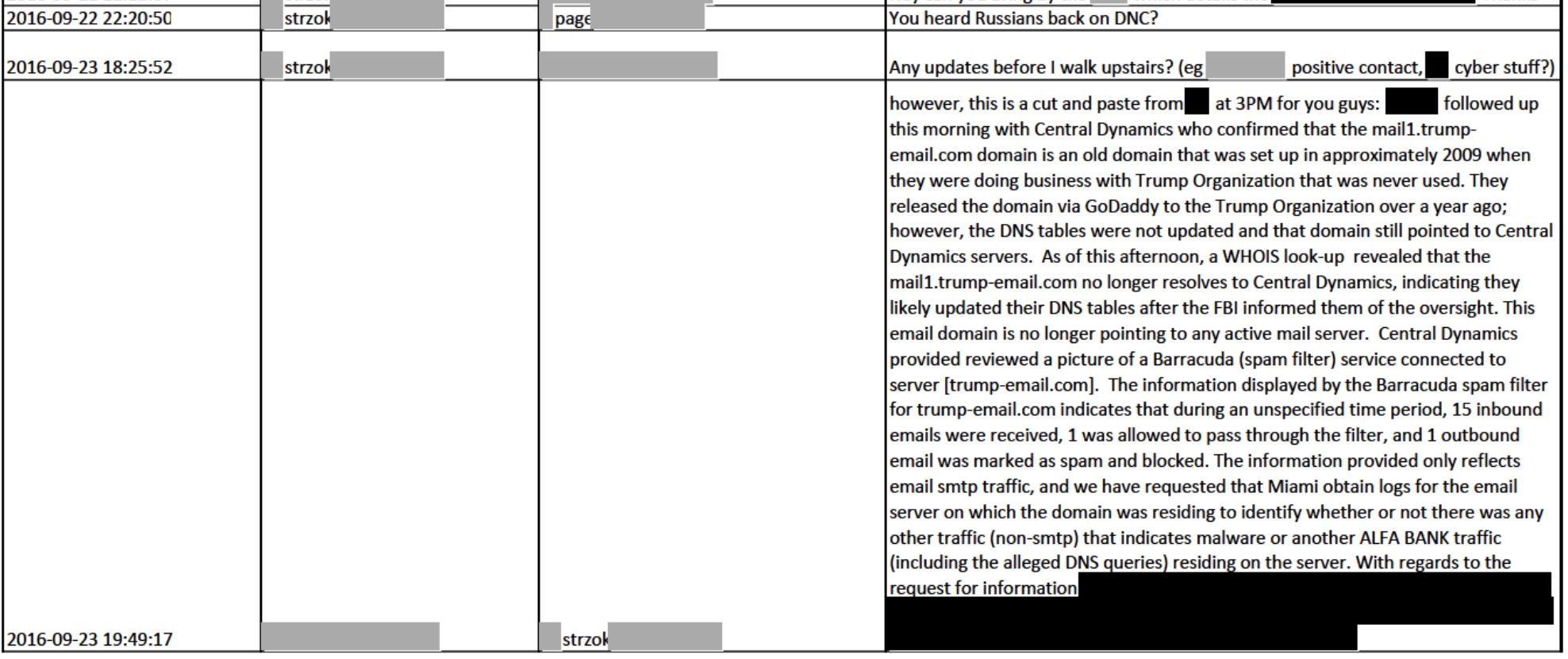

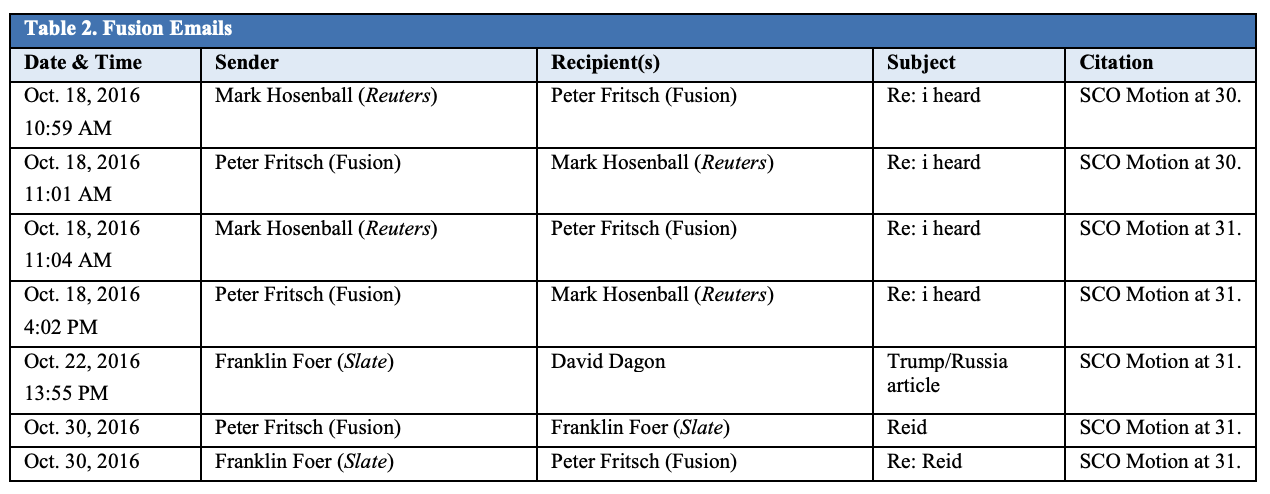

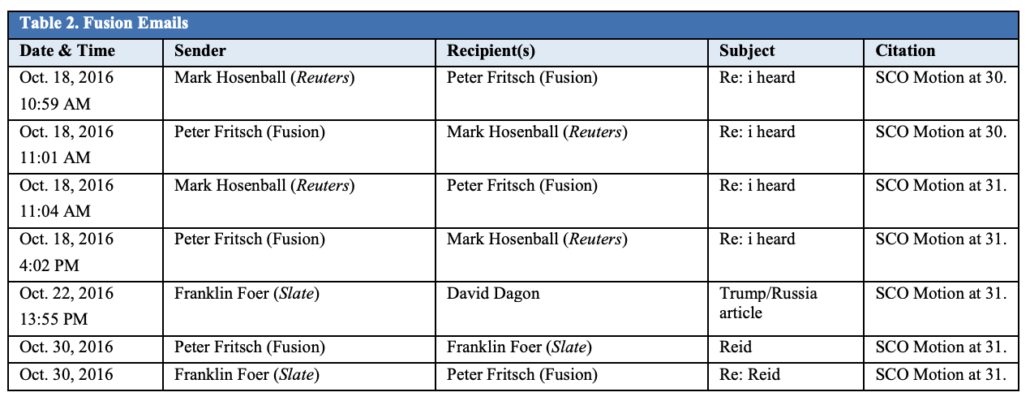

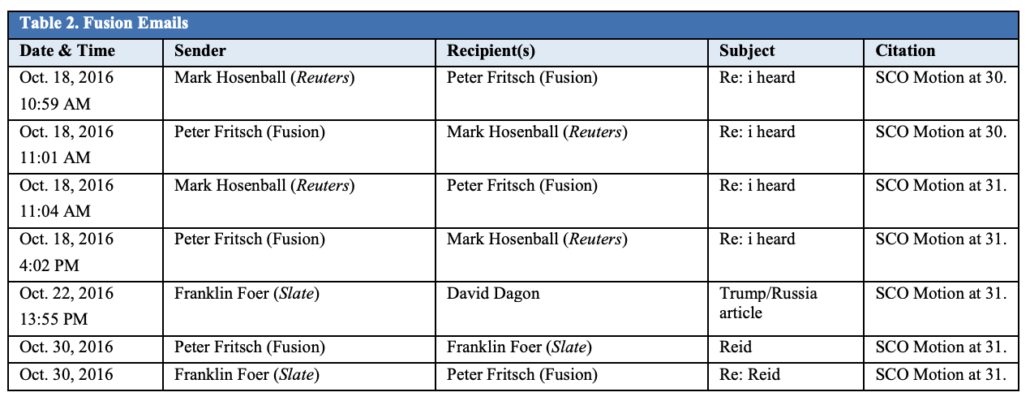

Indeed, new details in Sussmann’s filing make it clear that Durham has, as I suspected, replicated some of the erroneous assumptions that Alfa Bank did to sustain his conspiracy theories. Sussmann summarizes the journalist-involved communications to which Sussmann was not a party that Durham wants to introduce at trial.

This table puts names to the narrative Durham tells in his filing. Importantly, it reveals that the reporter who — in addition to making it clear he had gotten to Fusion’s “experts via different channels,” raised questions about the source of the data (the same topic Durham’s expert doesn’t seem prepared to address) — is Mark Hosenball.

That’s important because, according to Fusion’s lawyer Joshua Levy, Hosenball sent Fusion the link to Tea Leaves’ data, not vice versa. It’s not clear whether this later email reflects Hosenball sending that link (plus there’s a discrepancy between what date Durham says these emails were exchanged and what date Sussmann does, October 16 and October 18 respectively), but if so, it would mean Hosenball was shopping data that had been available via other means, means that aren’t known to involve Sussmann or Fusion.

In other words, just a single one of these later emails that Durham is pointing to to support his claim that Democrats were pushing this story involves the Democrats taking the initiative, and it only involves Peter Fritsch forwarding this story and pushing Foer to hurry up on his own story (which he sourced to Tea Leaves and Camp) on the Alfa Bank anomaly.

That’s important because Durham completely leaves out of his narrative how Sussmann helped kill the initial NYT story, and now he says that helping the FBI kill a story on his client’s opponent just before an election would not be exculpatory.

As a reminder, Sussmann testified to HPSCI that the reason he shared the information with the FBI was to provide them the maximum flexibility to decide what to do with it.

I was sharing information, and I remember telling him at the outset that I was meeting with him specifically, because any information involving a political candidate, but particularly information of this sort involving potential relationship or activity with a foreign government was highly volatile and controversial. And I thought and I remember telling him that it would be a not-so-nice thing ~ I probably used a word more stronger than “not so nice” – to dump some information like this on a case agent and create some sort of a problem. And I was coming to him mostly because I wanted him to be able to decide whether or not to act or not to act, or to share or not to share, with information I was bringing him to insulate or protect the Bureau or — I don’t know. just thought he would know best what to do or not to do, including nothing at the time.

And if I could just go on, I know for my time as a prosecutor at the Department of Justice, there are guidelines about when you act on things and when close to an election you wait sort of until after the election. And I didn’t know what the appropriate thing was, but I didn’t want to put the Bureau or him in an uncomfortable situation by, as I said, going to a case agent or sort of dumping it in the wrong place. So I met with him briefly and

Q Did you meet — was it a personal meeting or a phone call?

A Personal meeting.

Q At the FBI?

A At the FBI. And if I could just continue to answer your question, and soI told him this information, but didn’t want any follow-up, didn’t ~ in other words, I wasn’t looking for the FBI to do anything. I had no ask. I had no requests. And I remember saying, I’m not you don’t need to follow up with me. I just feel like I have left this in the right hands, and he said, yes.

He described then how Baker called him back and asked him for the name of the journalist who was about to publish the story.

Q The conversations you had with the journalists, the ~

A Oh, excuse me. I did not recall a sort of minor conversation that I had with Mr. Baker, which I don’t think it was necessarily related to the question you ‘asked me, but I just wanted to tell you about a phone call that I had with him 2 days after I met with him, just because I had forgotten it When I met with him, I shared with him this information, and I told him that there was also a news organization that has or had the information. And he called me 2 days later on my mobile phone and asked me for the name of the journalist or publication, because the Bureau was going to ask the public — was going to ask the journalist or the publication to hold their story and not publish it, and said that like it was urgent and the request came from the top of the Bureau. So anyway, it was, you know, a 5-minute, if that, phone conversation just for that purpose.

While it’s quite clear that Sussmann seeded the NYT story before his meeting and the follow-up phone call with Baker (and also spoke, at some time or another, to Foer and Ellen Nakashima), Durham provides no evidence that Sussmann — and even Fusion! — were doing anything more after FBI intervened to kill the story than responding to inquiries, inquiries that were largely based off Tea Leaves’ efforts.

They may well have been. Durham is not presenting any evidence of it.

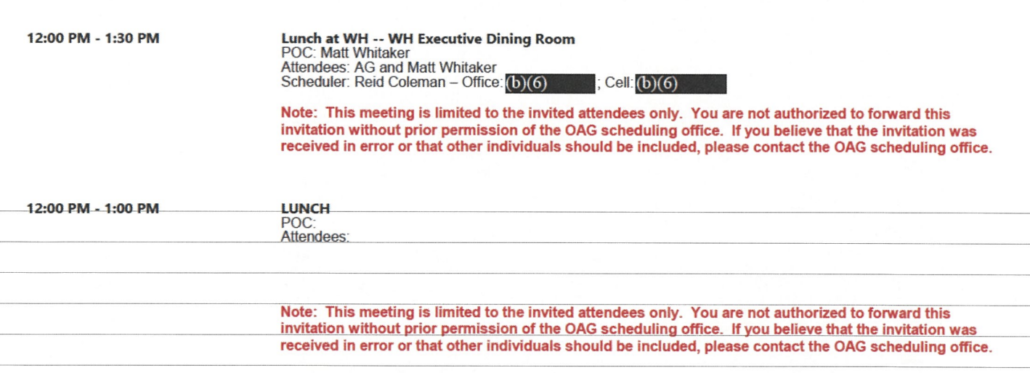

We know from discovery records that at the time that Durham indicted Sussmann, he had not yet bothered to chase this follow-up down. Altogether, there were 37 emails on top of the records of the face-to-face meeting where the FBI asked the NYT to hold the story.

On September 27, November 22, and November 30, 2021, the defense requested, in substance, “any and all documents including the FBI’s communications with The New York Times regarding any of [the Russian Bank-1] allegations in the fall of 2016.” In a subsequent January 10, 2022 letter, the defense also asked for information relating to a meeting attended by reporters from the New York Times, the then-FBI General Counsel, the then-FBI Assistant Director for Counterintelligence, and the then-FBI Assistant Director for Public Affairs. In response to these requests, the Special Counsel’s Office, among other things, (i) applied a series of search terms to its existing holdings and (ii) gathered all of the emails of the aforementioned Assistant Director for Public Affairs for a two-month time period, yielding a total of approximately 8,900 potentially responsive documents. The Special Team then reviewed each of those emails for relevant materials and produced approximately 37 potentially relevant results to the defense.

This was a significant effort to avoid a story about an ongoing investigation, one that helped FBI protect Trump.

And Sussmann believes — correctly — that the fact he helped the FBI kill a damaging story on Hillary’s opponent is exculpatory. Here’s what Sussmann says Joffe would say if he testified:

And the defense believes that, if called to testify, Mr. Joffe would offer critical exculpatory testimony, including that: (1) Mr. Sussmann and Mr. Joffe agreed that information should be conveyed to the FBI and to Agency-2 to help the government, not to benefit Mr. Joffe; (2) the information was conveyed to the FBI to provide a heads up that a major newspaper was about to publish a story about links between Alfa Bank and the Trump Organization; (3) in response to a later request from Mr. Baker, Mr. Sussmann conferred with Mr. Joffe about sharing the name of that newspaper before Mr. Sussmann told Mr. Baker that it was The New York Times; (4) the researchers and Mr. Joffe himself held a good faith belief in the analysis that was shared with the FBI, and Mr. Sussmann accordingly and reasonably believed the data and analysis were accurate; and (5) contrary to the Special Counsel’s entire theory, Mr. Joffe was neither retained by, nor did he receive direction from, the Clinton Campaign. [my emphasis]

To sustain his claim that there would be no benefit to the FBI in getting such a heads up and the opportunity — which they availed themselves of — to kill the story, Durham restates and seriously downplays the decision that both Joffe and Sussmann made to give the FBI the opportunity to kill the story.

The defendant’s further proffer that Tech Executive-1 would testify that (i) the defendant contacted Tech Executive-1 about sharing the name of a newspaper with the FBI General Counsel, (ii) Tech Executive-1 and his associates believed in good faith the Russian Bank-1 allegations, and (iii) Tech Executive-1 was not acting at the direction of the Clinton Campaign, are far from exculpatory. Indeed, even assuming that all of those things were true, the defendant still would have materially misled the FBI in stating that he was not acting on behalf of any client when, in fact, he was acting at Tech Executive-1’s direction and billing the Clinton Campaign. [my emphasis]

He makes no mention of the fact that FBI spent considerable effort — an effort made possible by Sussmann and Joffe — to protect the investigation and Trump. He doesn’t even admit that the reason why Sussmann asked Joffe about sharing Lichtblau’s name is so that the FBI could kill the story.

The YotaPhone that was not in Trump’s hands

Michael Sussmann could be putting up a far bigger stink that Durham wants to introduce Sussmann’s meeting with the CIA in February 9, 2017, especially the way that Durham keeps revealing inaccurate details about it. This is an event that happened five months after his alleged crime, one that (as Sussmann notes) could not be part of the same effort as Durham alleges the FBI meeting was about, because there no longer was a Hillary campaign.

He’s not. In fact, he says he has no problem with Durham introducing the February 9 meeting.

In any event, Mr. Sussmann does not object to the introduction of this discrete CIA statement pursuant to Rule 404(b).9 But Mr. Sussmann disagrees with the Special Counsel’s characterization and interpretation of that statement, and he reserves his right to introduce evidence rebutting the Special Counsel’s claims, including evidence that will demonstrate that Mr. Sussmann disclosed to CIA personnel that he had a client and that he had worked with political clients. See, e.g., Mem. of Conversation at SCO-3500U-010119-120 (Jan. 31, 2017) (“Sussman[n] said that he represents a CLIENT who does not want to be known. . . Sussman[n] would not provide the client’s identity and was not sure if the client would reveal himself . .”); id.at SCO3500U-010120 (“Sussman[n] is [] openly a Democrat and openly told [CIA personnel] that he does lots of work with DNC”).

The reason why Sussmann has no objection likely has to do with that January 31 document, which Durham posted to docket along with the memorialization of the February 9 meeting. Indeed, given the Bates stamp on the document — SCO-00081634 for the January 31 document as compared to SCO-074877 — Durham may have only obtained this document in response to Sussmann’s repeated requests for the complete list of the people he spoke with at the CIA.

In any case, both documents actually help Sussmann more than Durham. They show that even in the February 9 meeting, Sussmann was upfront about his ties to the Democrats and described the data source as private — the very same things Durham claims Sussmann was deliberately hiding from the FBI in September. In the January 31 meeting, he explicitly said he had a client and even conveyed that Joffe is a Republican.

Read together, these meeting records are consistent with Sussmann’s story: that he went to the government bringing data from someone — Joffe — who wanted it shared but was not otherwise asking Sussmann to intervene as a lawyer. On behalf of someone, but not making a formal request as a lawyer.

Very importantly, both meetings make it clear that the suspicion was not that Trump was using a YotaPhone, but that someone in his vicinity was. That’s because “there was once [sic] instance when Trumbo [sic] was not in Trump p Tower at but the phone was active on Trump tower WIFI network” and “the information provided would show instances when the Yota-phone and then candidate Trump were not believed to be collocated.” This is the description of someone suspected of infiltrating Trump’s campaign, not Trump secretly siding with Russia.

There are still problems with it: The claim that the phone moved to the White House with Trump is not possible because the phone moved in December 2016, when Obama was still occupying it (and to the extent that Trumpsters had moved to DC yet, Trump was working out of Trump Hotel). Given Durham’s claim that there was YotaPhone metadata at the White House going back to 2014, it’s unclear whether the phone at the White House in December 2016 could be the earlier phone or a Trump one.

For example, the more complete data that Tech Executive-1 and his associates gathered – but did not provide to Agency-2 – reflected that between approximately 2014 and 2017, there were a total of more than 3 million lookups of Russian Phone-Provider-1 IP addresses that originated with U.S.-based IP addresses. Fewer than 1,000 of these lookups originated with IP addresses affiliated with Trump Tower. In addition, the more complete data assembled by Tech Executive-1 and his associates reflected that DNS lookups involving the EOP and Russian Phone Provider-1 began at least as early 2014 (i.e., during the Obama administration and years before Trump took office) – another fact which the allegations omitted

But even Durham agrees there were YotaPhone look-ups from Trump’s vicinity, and while he doesn’t understand it, his own filing confirms that these phones are super rare. And given the description that the YotaPhone showed up in MI when Trump was interviewing a cabinet member (and given some things I’ve heard about this allegation), it does seem to tie the YotaPhone to Betsy DeVos.

John Durham has said the only reason you could write up details about DNS anomalies implicating Trump is malicious partisanship, and yet his filing does just that.

Still, the traffic might be most consistent with a Secret Service agent on Trump’s detail using a YotaPhone, something that — given the Secret Service’s never ending scandals — wouldn’t be the kind of thing you could rule out.

The story is consistent with Joffe and the researchers identifying — via DNS look-ups, not the servers at Trump Tower or the White House — that there was metadata reflecting something that could be a significant counterintelligence concern, one that had the intent of hurting Trump, not helping him. The frothers think it was a good thing that a spy on DiFi’s staff and another volunteering for an Eric Swalwell campaign were identified; but if it’s Trump, they want counterintelligence concerns to take a back seat.

And in retrospect, the possibility there was a Russian spy in Trump’s vicinity would be no big surprise, given his track record. His campaign manager admitted he had hidden his work for Ukrainian oligarchs and was hoping to exploit his ties to Trump to get paid by them and a Russian oligarch. His National Security Advisor admitted he had secretly been working for Turkey while getting classified briefings with the candidate. The guy who got him hired, who went on to run his Inaugural Committee, is accused of working for the Emirates when he did all that.

The only way that finding potential spies infiltrating Trump’s campaign would be an attack on his campaign is if he wanted those spies there.

Then again, that seems to be what Tom Barrack is going to use as his defense, so maybe that’s what is really driving this scandal.