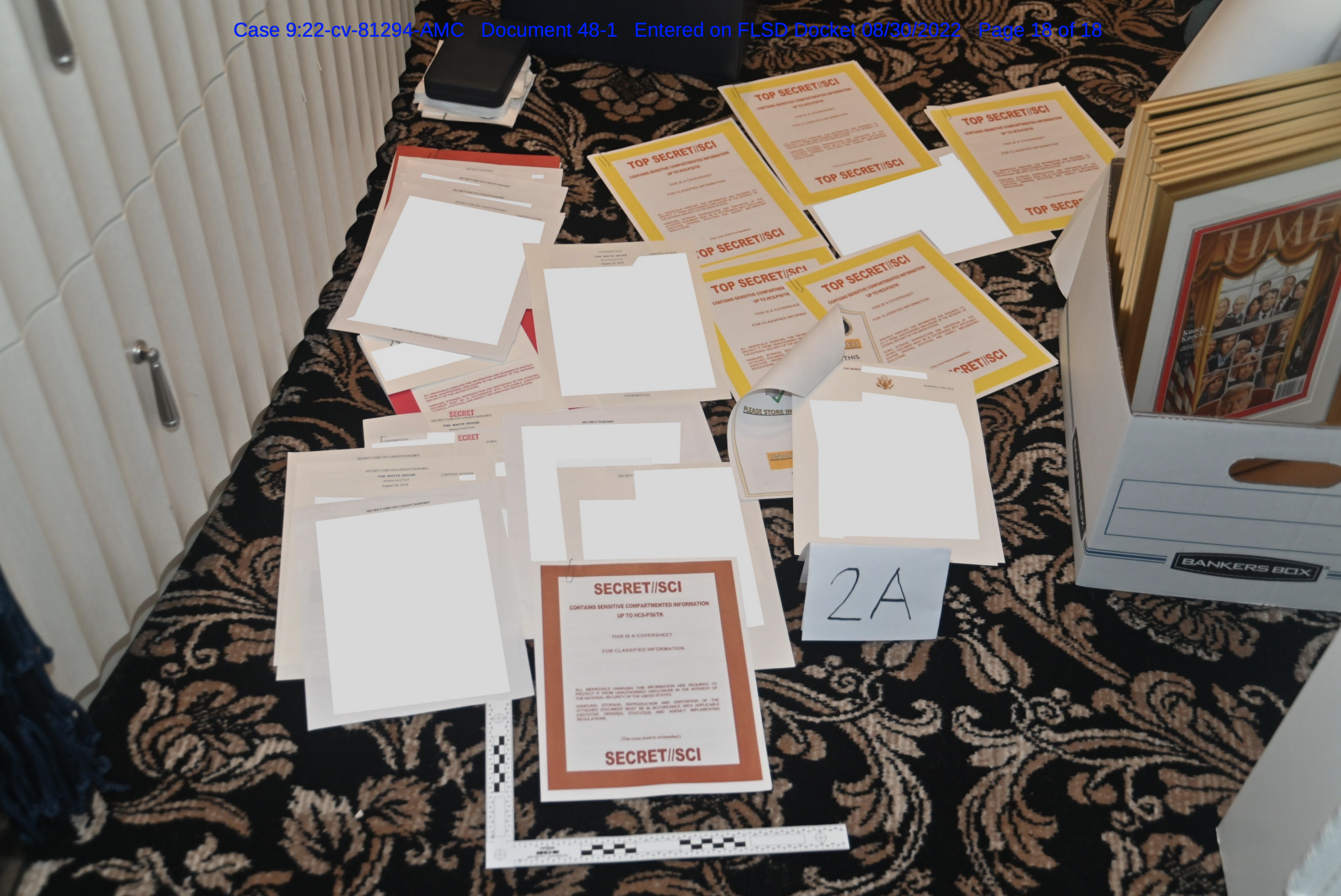

Back in November, Devlin Barrett (along with WaPo’s Trump-whisperer, Josh Dawsey) published a column claiming investigators had found nothing to suggest that Trump was trying to monetize the documents he stole.

That review has not found any apparent business advantage to the types of classified information in Trump’s possession, these people said. FBI interviews with witnesses so far, they said, also do not point to any nefarious effort by Trump to leverage, sell or use the government secrets. Instead, the former president seemed motivated by a more basic desire not to give up what he believed was his property, these people said.

I mocked Devlin’s credulity at the time. His story was utterly inconsistent with — and made no mention of — several details we (or I) already knew about the documents. It also showed no consideration of the value that the already-described documents would have for Trump’s business partners, the Saudis.

As Devlin Barrett’s sources would have it, a man whose business ties to the Saudis include a $2 billion investment in his son-in-law, a golf partnership of undisclosed value, and a new hotel development in Oman would have no business interest in stealing highly sensitive documents describing Iran’s missile systems.

The story was transparently an attempt by someone to prematurely cement an investigative conclusion, almost a month before the stay on DOJ’s access to the unclassified documents seized last August was lifted. Just two days later, Trump announced his bid for another Presidential term, and two days after that, Merrick Garland appointed Jack Smith, someone who had no partisan stake in issuing premature exoneration for Trump.

Yesterday, as the NYT published a second substantive story about Jack Smith’s subpoena for information about Trump’s business deals, Devlin published a perfunctory one. Even before he describes the subpoena, Devlin reports a single source concluding, as his sources concluded last November, “nothing to see here.”

But the inquiry produced little that wasn’t already publicly known, this person said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss an ongoing criminal investigation.

Prosecutors sought information on any real estate and development deals reached in China, France, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, the person said.

The Trump Organization’s public website lists only one deal in that time frame in one of those countries, Oman, and that deal was done after Trump left the White House.

Devlin’s story notes his earlier report, but not how wildly it conflicted with even the events known at the time, emphasizing China not Iran.

The Washington Post reported last year that while the classified documents included sensitive information about U.S. intelligence-gathering aimed at China, among other subjects, investigators did not see an obvious financial motive in the type of documents recovered from Mar-a-Lago.

NYT’s more substantive story on this inquiry expresses far less certainty than Devlin’s single attributed source about what the subpoena obtained, much less what Smith already had to support this line of inquiry.

The Trump Organization swore off any foreign deals while he was in the White House, and the only such deal Mr. Trump is known to have made since then was with a Saudi-based real estate company to license its name to a housing, hotel and golf complex that will be built in Oman. He struck that deal last fall just before announcing his third presidential campaign.

The push by Mr. Smith’s prosecutors to gain insight into the former president’s foreign business was part of a subpoena — previously reported by The New York Times — that was sent to the Trump Organization and sought records related to Mr. Trump’s dealings with a Saudi-backed golf venture known as LIV Golf, which is holding tournaments at some of his golf clubs. (Mr. Trump’s arrangement with LIV Golf was reached well after he removed documents from the White House.)

Collectively, the subpoena’s demand for records related to the golf venture and other foreign ventures since 2017 suggests that Mr. Smith is exploring whether there is any connection between Mr. Trump’s deal-making abroad and the classified documents he took with him when he left office.

It is unclear what material the Trump Organization has turned over in response to the subpoena or whether Mr. Smith has obtained any separate evidence supporting that theory.

Neither story describes whether the subpoena listed which crimes are under investigation. On that topic, the NYT, as part of boilerplate, repeats the same thing I do when I make boilerplate recitations of the crimes under investigation: 18 USC 793(e), refusing to return classified documents, and 18 USC 1519, obstruction of the efforts to get those classified documents back.

While establishing a motive for why Mr. Trump kept hold of certain documents could be helpful to Mr. Smith, it would not necessarily be required in proving that Mr. Trump willfully maintained possession of national defense secrets or that he obstructed the government’s repeated efforts to get the materials back. Those two potential crimes have long been at the heart of the government’s documents investigation.

Devlin uses similar boilerplate.

The Mar-a-Lago investigation has centered on two potential crimes — possible obstruction for not complying with the subpoena, and possible mishandling of national security secrets for keeping classified documents in an unauthorized location

We are — all of us, myself included — forgetting the third statute included on the search warrant that once seemed a mere backstop to the others, 18 USC 2071, intentionally removing government documents. That statute, which once upon a time might have been used as the crime to which Trump could plead down in a plea agreement, carries only a three year max sentence. But along with that sentence, it disqualifies someone convicted of it from holding public office, something that would be challenged constitutionally following any jury verdict but which would be waived under any plea deal.

Whoever, having the custody of any such record, proceeding, map, book, document, paper, or other thing, willfully and unlawfully conceals, removes, mutilates, obliterates, falsifies, or destroys the same, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both; and shall forfeit his office and be disqualified from holding any office under the United States.

I’ve always believed (as have experts I trust) that this would be a particularly hard crime with which to charge a former President, largely because a President has legal access to these documents until noon on January 20. But asking about business deals Trump might have been pursuing while in the presidency, all the way back to 2017, might provide evidence of intent that predates the actual removal of the documents.

And learning about Trump’s business deals with, especially, the Saudis, might develop evidence for 18 USC 794, the far more serious crime of providing intelligence to help a foreign government.

Let me caution, I still think it exceedingly unlikely that Smith is pursuing 794 charges against Trump for stealing documents and then selling them to the Saudis, to be paid in the form of golf tournaments and branding deals in Oman. Please don’t take from my mention of this that I’m predicting Smith is going to Go There. Rather, I suspect Smith is thinking of a package of potential charges that would give Trump an option to plead down quietly, one sufficiently ugly to make Republican politicians not want to join him in his fight. I’m merely stating that taking documents and refusing to give them back — which is the currently known lead charge in this investigation– is a dramatically different fact set than taking them and sharing them with a foreign government that pays you a lot of money, especially one that subsequently engaged in multiple actions — keeping gas prices high during the election and chumming up to China — that seem to have surprised the US intelligence community, as if some intelligence visibility had gone dark before those happened.

But let me go back to Devlin’s source’s certainty that there’s nothing to see there. It’s an odd claim to make given the number of other gaps in understanding that seem to exist in the understanding of those not directly participating in the investigation.

The story where NYT first broke the Trump business deal subpoena described at least five different subpoenas to Trump Org (though way down at the bottom of the story, it describes “numerous” subpoenas):

- The subpoena including the golf deal and — we now learn — all business deals Trump has chased since 2017

- A subpoena to Trump Organization seeking additional surveillance footage

- A subpoena to “the software company that handles all of the surveillance footage for the Trump Organization, including at Mar-a-Lago”

- First, a subpoena to Matthew Calamari, Jr.

- Then, a subpoena to Matthew Calamari, Sr.

Matthew Sr., at least, would have visibility on business deals with the Saudis and others. But all the reports on the two interviews with the Calamaris suggest they were focused, instead, on why Walt Nauta contacted them after DOJ first subpoenaed surveillance footage.

To resolve the issue about the gaps in the surveillance footage, the special counsel last week subpoenaed Matthew Calamari Sr, the Trump Organization’s security chief who became its chief operating officer, and his son Matthew Calamari Jr, the director of corporate security.

Both Calamaris testified to the federal grand jury in Washington on Thursday, and were questioned in part on a text message that Trump’s valet, Walt Nauta, had sent them around the time that the justice department last year asked for the surveillance footage, one of the people said.

The text message is understood to involve Nauta asking Matthew Calamari Sr to call him back about the justice department’s request, one of the people said – initially a point of confusion for the justice department, which appears to have thought the text was to Calamari Jr.

Most reporters assume the gaps DOJ is trying to close pertain to Nauta’s own actions in advance of Evan Corcoran’s search of the storage closet. I’m not sure. That’s because DOJ got sufficient visibility from what they did receive to list the storage closet, Trump’s office, and Trump’s residence in the search warrant supporting the August search of Mar-a-Lago. They got sufficient visibility to lead Nauta to revise his testimony afterwards. That’s why I emphasized in my last post on this that DOJ asked for five months of surveillance video, predating the day, by eight days, that Trump sent boxes to NARA in January 2022. The gaps in question might have shown other people, not Nauta, entering the storage closet, or have shown Nauta entering at times entirely removed from the date of the subpoena. If — strictly hypothetically — those gaps coincided with business meetings with foreigners at Mar-a-Lago, it would be a flashing siren saying, “look here for the good stuff.” It might also explain why Nauta immediately reached out to Calamari about the video, if he knew some of that video would show things that were far more damning than the mere attempt to obstruct a subpoena response.

If Nauta had involvement in earlier sketchy activities, predating the subpoena, it might explain why — as Hugo Lowell reported — Nauta fairly obviously attempted to monitor Evan Corcoran’s own search.

The notes described how Corcoran told Nauta about the subpoena before he started looking for classified documents because Corcoran needed him to unlock the storage room – which prosecutors have taken as a sign that Nauta was closely involved at essentially every step of the search.

Corcoran then described how Nauta had offered to help him go through the boxes, which he declined and told Nauta he should stay outside. But going through around 60 boxes in the storage room took longer than expected, and the search ended up lasting several days.

The notes also suggested to prosecutors that there were times when the storage room might have been left unattended while the search for classified documents was ongoing, one of the people said, such as when Corcoran needed to take a break and walked out to the pool area nearby.

One more thing that might explain prosecutors’ concerns about gaps in the surveillance footage is if they coincided with the times when Corcoran had left the room unattended.

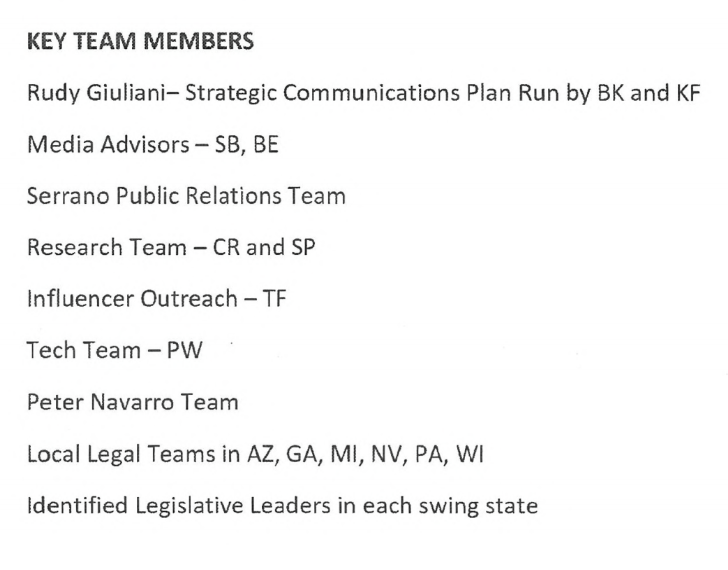

Yet every time someone writes about Nauta, they include language that might come from the vicinity of Stanley Woodward, the lawyer that Nauta shares with Kash Patel (as well as Peter Navarro and convicted seditionist Kelly Meggs and his wife), suggesting that it was a mistake not to immunize Nauta, as DOJ did with Kash, because it has prevented them from substantiating an obstruction case. The version of this in the NYT — which reflects the kind of internal DOJ dissent that WaPo has reported regarding a push to adopt a more cooperative stance in advance of the search — is especially unpersuasive.

Last fall, prosecutors faced a critical decision after investigators felt Mr. Nauta had misled them. To gain Mr. Nauta’s cooperation, prosecutors could have used a carrot and negotiated with his lawyers, explaining that Mr. Nauta would face no legal consequences as long as he gave a thorough version of what had gone on behind closed doors at the property.

Or the prosecutors could have used a stick and wielded the specter of criminal charges to push — or even frighten — Mr. Nauta into telling them what they wanted to know.

The prosecutors went with the stick, telling Mr. Nauta’s lawyers that he was under investigation and they were considering charging him with a crime.

The move backfired, as Mr. Nauta’s lawyers more or less cut off communication with the government. The decision to take an aggressive posture toward Mr. Nauta prompted internal concerns within the Justice Department. Some investigators believed that top prosecutors, including Jay Bratt, the head of the counterespionage section of the national security division at the Justice Department, had mishandled Mr. Nauta and cut off a chance to win his voluntary cooperation.

More than six months later, prosecutors have still not charged Mr. Nauta or reached out to him to renew their conversation. Having gotten little from him as a witness, they are still seeking information from other witnesses about the movement of the boxes.

If being misled by Nauta led prosecutors to look more closely at the larger timeline of the missing surveillance video, only to find suspect ties to the Saudis, it was in no way a mistake. On the contrary, Woodward’s own decisions would have directly led to intensified scrutiny of his client (as his decisions similarly are, in the effort to get Navarro to turn over Presidential Records Act documents).

And there’s something that is routinely missed in all of this coverage. The Guardian’s Lowell rightly suggests that because Trump didn’t directly tell Corcoran to search only the storage closet, it might present challenges to an obstruction case. But Trump’s choice to use Nauta as an obvious gatekeeper makes it far easier to charge Nauta with 18 USC 793(g), conspiring to hoard classified documents. So the observation that DOJ hasn’t chosen to charge Nauta with just false statements in the interim six months should in no way be taken as solace by Nauta, because what has happened in the interim puts him at risk of charges that carry a ten year sentence for each document in question rather than the few months he might face for lying to the FBI.

Nauta’s not the only one who might insulate Trump from obstruction charges but expose all of them to greater Espionage Act danger.

Witness the evolution of how Tim Parlatore described Boris Epshteyn’s role in the investigation. In March, Parlatore described that, until such time as Boris started being treated as a target, his access to people “inside the palace gates” was useful.

Mr. Epshteyn’s legal role with Mr. Trump, while less often focused on gritty legal details, has been to try to serve as a gatekeeper between the lawyers on the front lines and the former president, who is said to sometimes roll his eyes at the frequency of Mr. Epshteyn’s calls but picks up the phone.

“Boris has access to information and a network that is useful to us,” said one of the team’s lawyers, Timothy Parlatore, whom Mr. Epshteyn hired. “It’s good to have someone who’s a lawyer who is also inside the palace gates.”

Mr. Parlatore suggested that he was not worried that Mr. Epshteyn, like a substantial number of other Trump lawyers, had become at least tangentially embroiled in some of the same investigations on which he was helping to defend Mr. Trump.

“Absent any solid indication that Boris is a target here, I don’t think it affects us,” Mr. Parlatore said.

But in the wake of Parlatore’s departure from Trump’s legal team a week ago, he went on Paula Reid’s show (on whose show he had earlier told an utterly ridiculous story about Trump using classified folders to block a light by the side of his bed) and lambasted Boris as an impediment to communication between Trump and his lawyers.

Boris Epshteyn [] had really done everything he could to try to block us [the lawyers], to prevent us from doing what we could to defend the President, and ultimately it got to a point where — it’s difficult enough fighting against DOJ and, in this case, Special Counsel, but when you also have people within the tent that are also trying to undermine you, block you, and really make it so that I can’t do what I know that I know that I need to do as a lawyer, and when I’m getting in the fights like that, that’s detracting from what is necessary to defend the client and ultimately was not in the client’s best interest, so I made the decision to withdraw.

[snip]

He served as kind of a filter to prevent us from getting information to the client and getting information from the client. In my opinion, he was not very honest with us or with the client on certain things. There were certain things — like the searches that he had attempted to interfere with, and then more recently, as we’re coming down to the end of this investigation where Jack Smith and ultimately Merrick Garland is going to make a decision as to what to do – as we put together our defense strategy to help educate Merrick Garland as to how best to handle this matter, he was preventing us from engaging in that strategy. [my emphasis]

At one level, this publicity stunt appears to be an attempt to persuade Trump that he should fire Boris. WaPo’s coverage of this clash describes that Parlatore’s public appearance followed what seems to have been a “he goes or we go” meeting with Trump a week ago (though Jim Trusty, at least thus far, has not chosen to follow Parlatore).

Before this weekend’s public feud, members of Trump’s legal team tried to settle the conflict quietly. Parlatore and another lawyer for Trump, James Trusty, recently traveled to Florida to advise Trump that he needed to remove Epshteyn from the document case and the 2020 election case, according to a person familiar with the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity to reveal private deliberations. Smith, the special counsel, is tasked with investigating both cases.

[snip]

Trump did not appear to take Parlatore and Trusty’s advice, as Epshteyn remained in his role as a key legal adviser and coordinator to Trump.

Parlatore has said he’d be willing to return if Boris were gone.

At another level, Parlatore seems to be getting out while the getting is good, shortly before any charges are filed, so he’s not stuck defending an uncooperative client who won’t pay his bills. (Update: WSJ reports that the investigation is all but done and some associates are prepping for Trump to be charged.) The publicity stunt gives him the first say on who is responsible for what comes next, too. If Trump gets charged, Tim Parlatore didn’t fuck up, Boris did.

The publicity stunt, with its claim that Boris lied to both him and Trump, may also be an attempt to insulate Trump. As such it may be little different than the ridiculous folder-on-the-bedside-light story.

But Parlatore’s response to Reid’s follow-up on Parlatore’s claim that Boris interfered with searches may be more than that.

Reid: What searches are those?

Parlatore: This is the searches at Bedminster, um, initially. There was a lot of pushback from him where he didn’t want us doing the search and we had to, eventually, overcome him.

Reid: Why didn’t he want you to do the search?

Parlatore: I don’t know.

Trump’s lawyer do not know — never have! — why Boris was so reluctant to allow a search of the property to which Trump flew to host a Saudi golf tournament directly after failing to comply with a subpoena.

Immediately after that exchange, Reid invited Parlatore to clarify that when he testified to the grand jury in December, he did so in lieu of any custodian of records for the searches done on Mar-a-Lago. Parlatore clarified he did not testify in response to a subpoena and on several occasions, when he offered to come back and clarify, prosecutors declined his generous offer.

Reid then gave him an opportunity to explain why the claims Parlatore made to Congress (which conflicted with known facts and which Epshteyn declined to sign) didn’t fundamentally conflict with the insta-declassification story Boris has told. Parlatore left me convinced that everyone is lying, meaning by choosing to retain Boris over Parlatore, Trump is just picking which lie he finds more convenient.

Nevertheless, Parlatore got his story out. He got to describe how the story he planned to tell Merrick Garland doesn’t conflict with the currently operative declassification story and more importantly, that if his December testimony to the grand jury was incomplete in any way, it’s all Boris’ fault.

Parlatore said, midway between his testimony and now, that if Boris started looking like a target, he might be in trouble. But in the wake of a two day interview between Boris and Smith’s attorneys and in the wake of subpoenas that raise increased questions about why Boris may have tried to prevent any search of the property at which Trump hosted the Saudis immediately after Trump blew off a subpoena, Parlatore took to the TV and offered his defense. If Jack Smith finds the Bedminster obstruction interesting enough, Parlatore may well have earned himself a subpoena.

The belated, convenient description of Boris as a filter rather than worthwhile access “inside the palace gates” is particularly interesting given WaPo’s description about what kind of advice Boris gave, in lieu of legal advice.

Epshteyn, a lawyer, had helped guide communications for Trump’s campaign and the White House.

According to the source, Parlatore and Trusty argued that the lawyers needed to focus on protecting Trump legally, not politically.

A source close to the Trump campaign who spoke on the condition of anonymity to disclose the team’s private thinking defended Epshteyn and said he is focused on protecting Trump from a variety of angles, whether it’s legal, political or related to the media.

Parlatore imagines he was trying to defend Trump legally. Boris thinks he’s defending Trump from a “variety of angles,” one of which is politics. That’s consistent with how Boris billed his time, which until after the August search he billed as political consulting. But it also suggests Boris was not just a gap in Parlatore’s knowledge, but also a gap in any privilege claims Trump can make over the others.

If Trump’s own ex-lawyer says that Boris was lying to both sides about what went on there’s a big gap in anyone’s knowledge — at least outside the team that has been investigating for a year.

Plus there’s all the stuff — even beyond the evidence collected in this investigation that DOJ would have obtained about these particular documents — that DOJ already knows.

During the Mueller investigation, for example, DOJ spent some time investigating how Trump shared highly classified Israeli intelligence with Russia just days after he fired Jim Comey. That includes the way in which White House staffers altered the MemCon of that meeting (much as, years later, the White House would alter the MemCon of Trump’s perfect phone call with Volodymyr Zelenskyy). That particular leak of classified information did not violate US law, because as President, Trump could declassify it. But it is precedent for Trump sharing the secrets of America and its allies with foreign countries that have helped him.

More directly on point, DOJ has abundant evidence regarding Trump’s approval of Tom Barrack’s efforts to tailor US policy to serve the Emirates and, secondarily, the Saudis, including to treat Mohammed bin Salman with full diplomatic status. On Barrack’s request, during the course of discovery, DOJ obtained a great deal of information from other agencies about Trump’s policy towards the Gulf Kingdoms. DOJ’s prosecution of Barrack ended in failure. But what it showed is that from the very start, the guy who got Paul Manafort hired did so knowing he could use it to promise to shape US policy to the Emirates’ interests. Like sharing classified information with Russia in 2017, Trump’s choice to shape US policy to serve the Emiratis and Saudis is not illegal. It’s only after he left the presidency where a quid pro quo could be important.

Unless, of course, such business discussions started earlier.

Again, I want to emphasize that I’m not saying Jack Smith is about to indict Trump for selling US secrets to the Saudis. But investigative developments reported out in the last several weeks have suggested that this investigation may not be the obstruction investigation everyone is treating it as.

Instead, Jack Smith may get to obstruction via a conspiracy to hoard classified documents.

Update: Corrected date on NARA document return.