Yes, It Turned Out January 6 Committee Endangered the DOJ Investigation by Withholding the Jeremy Bertino Transcript in June

I often get accused of being an uncritical booster for DOJ on the January 6 investigation. In reality, I have focused my criticism on real problems with the investigation.

In fact several of the criticisms I’ve raised have borne out in recent days, as an attorney-client conflict that should have been identified in June threatened (and still threatens) to bollox the Proud Boy Leader trial, and with it the larger effort to tie Trump’s immediate associates with the crime scene.

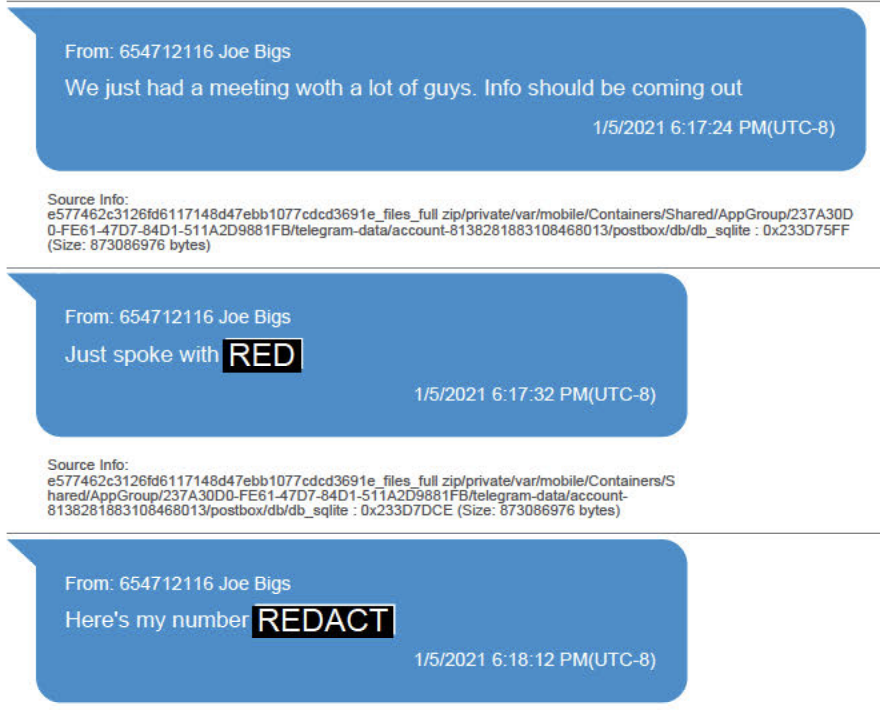

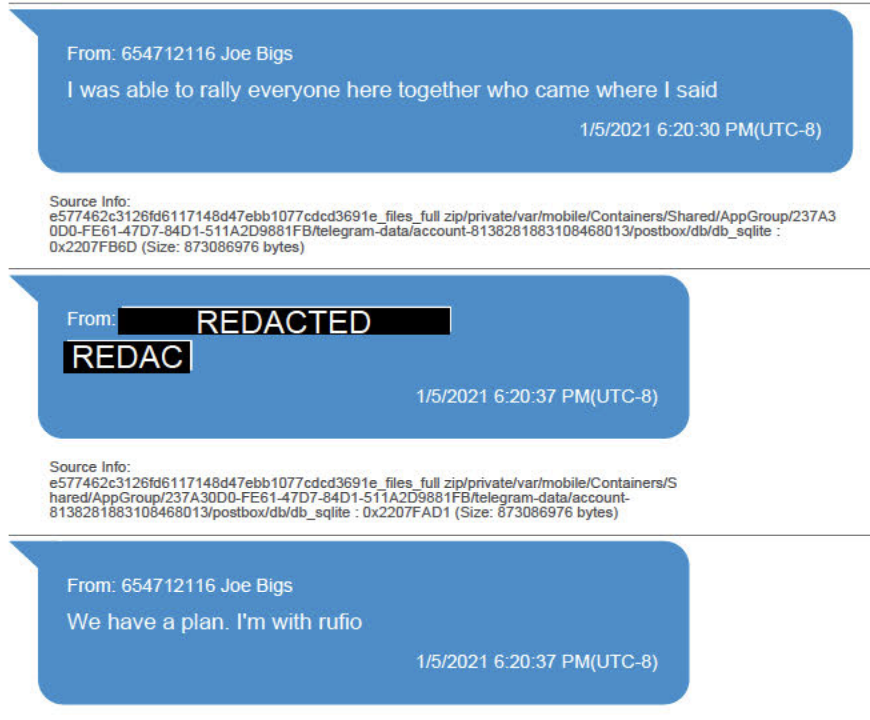

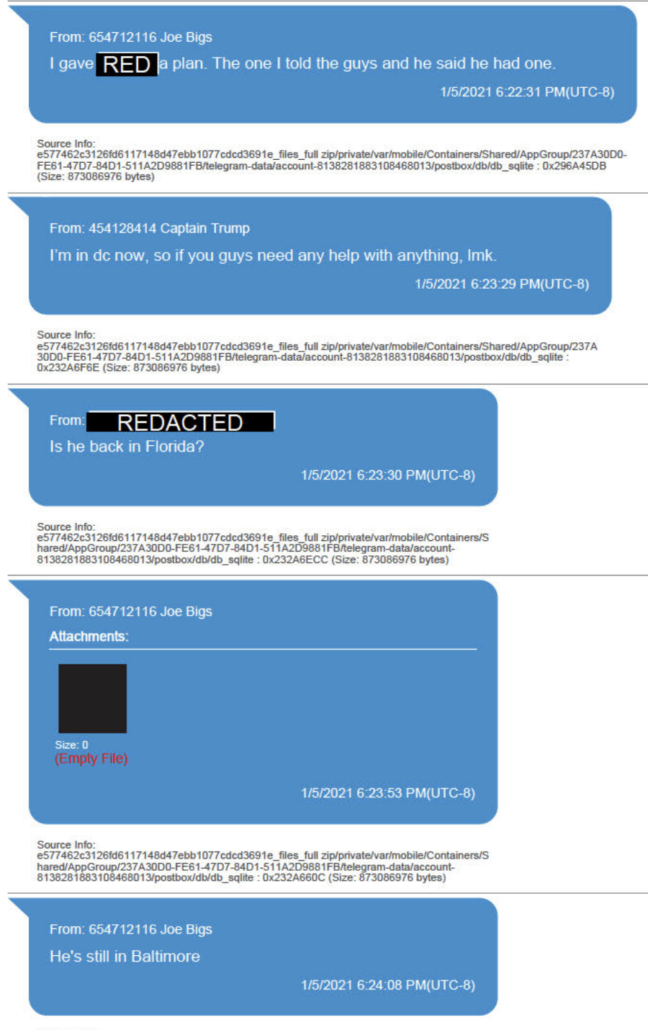

Twice, for example, I’ve discussed how central Joe Biggs’ actions the day of the attack were to understanding the larger event. In the first, I described how Biggs’ chumminess with FBI agents led them to overlook his plans for a terrorist attack on the Capitol.

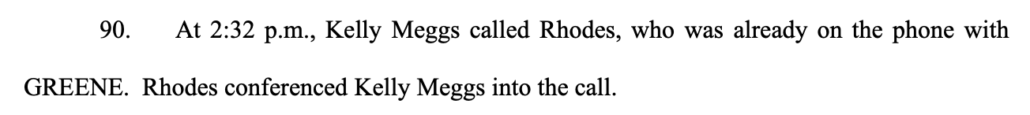

Something brought Joe Biggs, Florida Oath Keepers Kenneth Harrelson and Jason Dolan, along with former Biggs employer Alex Jones to the top of the East steps, along with the mob that Jones brought on false pretenses. Shortly thereafter, Florida Oath Keeper head Kelly Meggs would bring a stack of Oath Keepers through the same door and — evidence suggests — in search of Nancy Pelosi, whom Meggs had talked about killing on election day.

Joe Biggs kicked off the riot on the West side of the building.

Then he went over to the East side to join his former employer Alex Jones and a bunch of Oath Keepers, led by fellow Floridians, to lead a mob back into the Capitol.

West side. Joe Biggs. East side. Joe Biggs.

This is the guy a couple of FBI Agents in Daytona believed was a credible informant against Antifa.

A month later, I described how problematic it was that an AUSA who played a part in Sidney Powell’s efforts to spread false claims about Mike Flynn and Joe Biden before the 2020 election had a role (now reportedly expanded) in overseeing the prosecution of Biggs.

Because of Joe Biggs’ role at the nexus between the mob that attacked Congress and those that orchestrated the mob, his prosecution is the most important case in the entire January 6 investigation. If you prosecute him and his alleged co-conspirators successfully, you might also succeed in holding those who incited the attack on the Capitol accountable. If you botch the Biggs prosecution, then all the most important people will go free.

Which is why it is so unbelievable that DOJ put someone who enabled Sidney Powell’s election season lies about the Mike Flynn prosecution, Jocelyn Ballantine, on that prosecution team.

All that was clear by September 2021.

In that same time period, I was complaining and complaining and complaining about DOJ’s lackadaisical approach to attorney conflicts, first as John Pierce racked up 20 clients, most who served as a firewall to Biggs and the other Proud Boy leaders, and later as DOJ waited three months before inquiring into Sidney Powell’s alleged role in funding some of the Oath Keeper’s defense teams.

The importance to the Trump investigation of getting the militia conspiracies that implicate Roger Stone and Alex Jones right is one of the reasons I argued, in June 2022, that it was urgent for the Proud Boys’ prosecution team to get Jeremy Bertino’s transcript sooner rather than later.

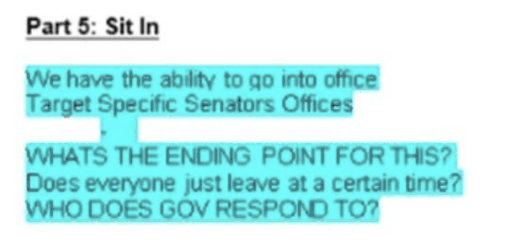

On June 6, DOJ charged the Proud Boy Leaders with sedition. As I noted at the time, the single solitary new overt act described in the indictment involved Jeremy Bertino, Person-1, seeming to have advance knowledge of a plan to occupy the Capitol.

107. At 7:39 pm, PERSON-1 sent two text messages to TARRIO that read, “Brother. ‘You know we made this happen,” and “I’m so proud of my country today.” TARRIO responded, “I know” At 7:44 pm. the conversation continued, with PERSON-1 texting, “1776 motherfuckers.” TARRIO responded, “The Winter Palace.” PERSON-1 texted, “Dude. Did we just influence history?” TARRIO responded, “Let’s first see how this plays out.” PERSON-1 stated, “They HAVE to certify today! Or it’s invalid.” These messages were exchanged before the Senate returned to its chamber at approximately 8:00 p.m. to resume certifying the Electoral College vote.

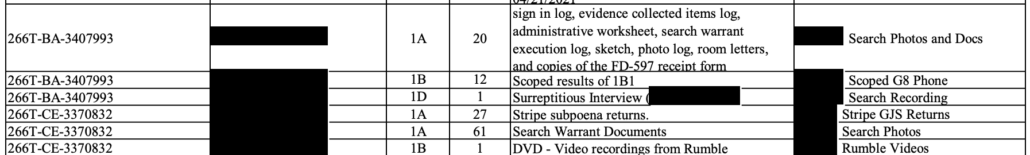

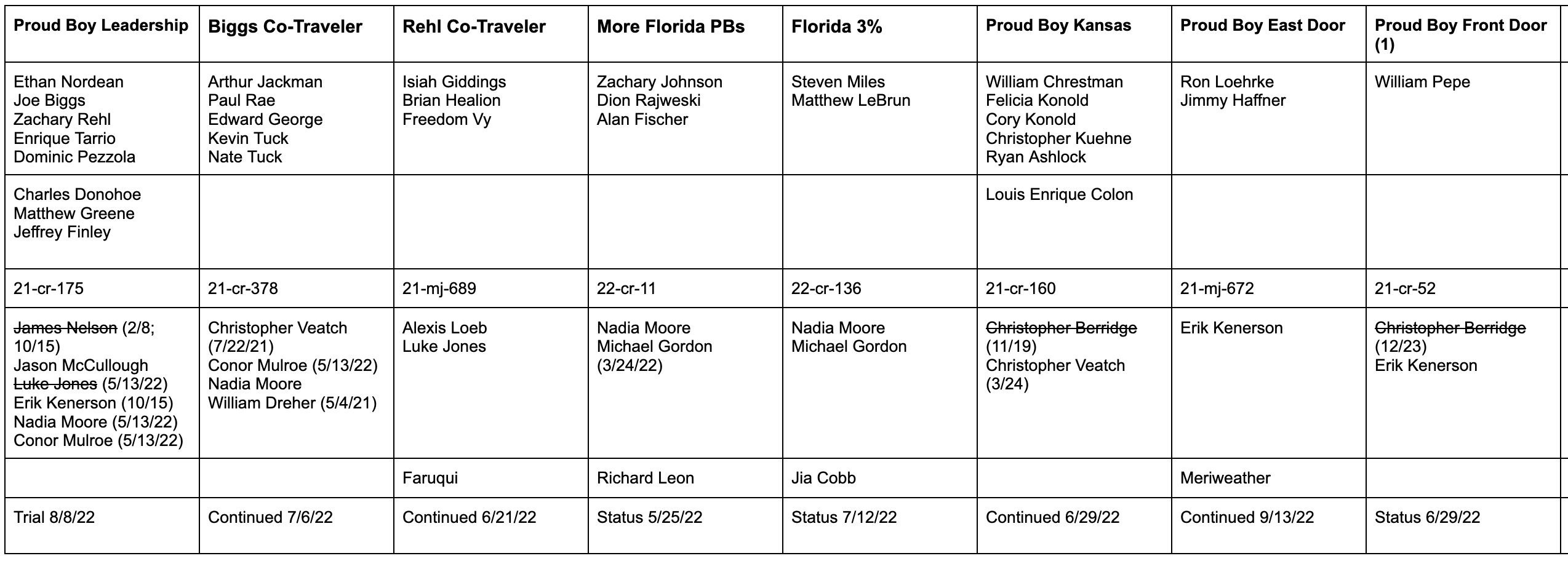

Just days earlier, as part of a discovery dispute, prosecutors had provided this (dated) discovery index. For several reasons, it’s likely that at least some these entries pertain to Bertino, because the CE ones are from the Charlotte office, close to where he lives, because he’s one of the three uncharged co-conspirators of central importance to the Proud Boys efforts, and because we know FBI did searches on him.

In a hearing during the day on June 9, the Proud Boys’ attorneys accused DOJ of improperly coordinating with the January 6 Committee and improperly mixing politics and criminal justice by charging sedition just before the hearings start. In the hearing there was an extensive and repeated discussion of the deposition transcripts from the committee investigation. AUSA Jason McCullough described that there had been significant engagement on depositions, but that the January 6 Committee wouldn’t share them. As far as he knew, the Committee said they would release them in September, which would be in the middle of the trial. Joe Biggs’ attorney insisted that DOJ had the transcripts, and that they had to get them to defendants.

Judge Tim Kelly ordered prosecutors that, if they come into possession of the transcripts, they turn them over within 24 hours.

Hours later, during the first (technically, second) January 6 Committee hearing, the Committee included a clip from Bertino describing how membership in the Proud Boys had tripled in response to Trump’s “Stand Back and Stand By” comment.

His cooperation with the Committee was not public knowledge. I have no idea whether it was a surprise to DOJ, but if it was, it presented the possibility that, in the guise of cooperating, Bertino had just endangered the Proud Boy sedition prosecution (which wouldn’t be the first time that “cooperative” Proud Boys proved, instead, to be fabricators). At the very least, it meant his deposition raised the stakes on his transcript considerably, because DOJ chose not to charge him in that sedition conspiracy.

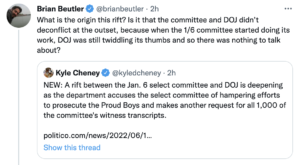

Today, in response to a bid by Dominic Pezzola and Joe Biggs to continue the trial until December, DOJ acceded if all defendants agree (Ethan Nordean won’t do so unless he is released from jail). With it they included a letter they sent yesterday to the Committee — following up on one they sent in April — talking about the urgency with which they need deposition transcripts.

We note that the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol (“Select Committee”) in its June 9, 2022 and June 13, 2022, hearings extensively quoted from our filings in active litigation and played portions of interviews the Select Committee conducted of individuals who have been charged by the Department in connection with the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.

It is now readily apparent that the interviews the Select Committee conducted are not just potentially relevant to our overall criminal investigations, but are likely relevant to specific prosecutions that have already commenced. Given this overlap, it is critical that the Select Committee provide us with copies of the transcripts of all its witness interviews. As you are aware, grand jury investigations are not public and thus the Select Committee does not and will not know the identity of all the witnesses who have information relevant to the Department’s ongoing criminal investigations. Moreover, it is critical that the Department be able to evaluate the credibility of witnesses who have provided statements to multiple governmental entities in assessing the strength of any potential criminal prosecutions and to ensure that all relevant evidence is considered during the criminal investigations. We cannot be sure that all relevant evidence has been considered without access to the transcripts that are uniquely within the Select Committee’s possession.

The discovery deadline for the Proud Boy case is tomorrow. If DOJ put Bertino before a grand jury and he said something that conflicts with what he told the Committee, it could doom his reliability as a witness, and with it the Proud Boys case, and with it, potentially, the conspiracy case against Trump.

Less than a week before I wrote that, there’s reason to believe, DOJ had flipped a key witness in the case.

It appears that DOJ did not get Jeremy Bertino’s transcript until around December 7. DOJ promised to give transcripts to the defendants within 24-hours after they received them, and DOJ provided 16-January 6 Committee transcripts on December 8.

And we now know the Bertino transcript was utterly critical to preparing for the trial, which is about to kick off. That’s because, in his deposition with the committee, Bertino explained at length both what appeared to be an attempt, by Joe Biggs’ attorney Dan Hull, to tie representation in a civil lawsuit to a deposition in the trial, and because Bertino had conversations with Hull on the day his girlfriend’s home was searched (which is probably when the FBI found the unregistered weapons described in Bertino’s plea paperwork).

A Yes. So I’m going to go back in my memory and try to remember the first time that I spoke with him. I believe it was after I received a civil suit from a church. I reached out to Enrique Tarrio and said, hey, I just got this subpoena or notice of civil suit. I think I need an attorney. And he’s like, oh, well, I’ll talk to Dan, my attorney, and I’ll see if he’ll take it for you. So I said okay. Couple of weeks went by, I didn’t hear anything. I got back in touch with Enrique and asked him, I said, hey, have you talked to your lawyer? And he’s, like, oh, yeah, Dan said he’ll do it for you pro bona because you were stabbed, but he wants to talk to you.

And so he sent me his phone number and I called Dan. I can’t remember when, what date, I don’t remember the specific details, but I do remember calling him and him basically asking me — or I was asking him about representing me in the case and he said oh, sure, sure, sure, we’ll get to that. But he was interested in possibly having me take the stand in the Joe Biggs’ trial about my stabbing to show why Joe was wearing body armor when he was in D.C. because there was a lot of talk after I was stabbed about guys making sure you had a stab proof vest on and stuff like that.

So I think his original intent was to get me on board to help his client. And then the next — I believe the next interaction I had was when I — Jay Thaxton reached out to me and was looking for representation for his deposition. And I said, hey, give this guy Dan a call. I sent him Dan’s number. And I guess Dan took care of his deposition, which I, you know, when I kind of heard what happened there, that’s when I became reluctant to have him represent me in this.

He didn’t seem very stable on the phone. I started to really listen to when he was talking and his rants, and I was, like, okay, this guy– I don’t think this guy’s great for me.

And then the morning that the FBI raided my girlfriend’s house I reached out to him because he was the only attorney that I knew and I was just kind of asking him for advice on how to handle everything.

And I specifically asked him for a retainer, like, can we sign a retainer paperwork, and he was, like, not right now, not right now. And I said okay.

Then a few days later, he asked — he called me — he would call me randomly late at night and go on, like, an hour rant about how the Proud Boys were little girls and just, I mean, off the rail conversations. I didn’t know what he was talking about. I was, like, my brain was popping trying to figure out what he was talking about. Then I believe he came to me and said, well, I’m going to — he said, do you want me to accept service on your behalf for the congressional thing, he said, but I’m not going to be able to be there because that date doesn’t work for me, so you’re going to have to go do it on your own.

I said no — and this was on a phone conversation, not a text conversation — I said no. He’s like, well, take 48 hours and think about it. This was on like a — I don’t even remember what day, but I believe it was the day before he actually accepted service from you guys. And he never got confirmation from me to accept service.

He said, well, just take 48 hours and think about it. I said, okay.

Next phone call I got from him was, hey, I accepted service, your date for your deposition is this day, and I’m not going to be there so you’re going to be on your own.

And that is pretty much when I cut off contact, I stopped responding to his calls and his text messages, and I hired Mr. Wellborn.

Bertino’s prior conversations with Hull were made all the more urgent because Norm Pattis, Alex Jones’ attorney, just got kicked off the case after having his license suspended in Connecticut for violating the Sandy Hook protective order, something we all knew was coming since November. [Update: Judge Tim Kelly is letting Pattis stay on the team, though it’s unclear in what role.]

Yesterday and today, Judge Tim Kelly hammered out some plan whereby Hull will be prevented from questioning Bertino, but that in no way eliminates the conflict. That in no way eliminates the risk of having Hull serve as the sole attorney in a case where he had privileged conversations with one of the key cooperating witnesses.

The J6C Committee is significantly to blame about this — at least by the time Bertino’s plea became public, they had to have recognized this conversation needed to be shared with prosecution.

But DOJ itself should have raised conflict issues with Pattis. At the time he joined Biggs’ team last summer, he was already representing Jones’ sidekick, Owen Shroyer, who had a bunch of calls with both Ethan Nordean and Biggs in advance of and during the attack.

Other, more prominent members of the Proud Boys appear to have been in contact with Jones and Shroyer about the events of January 6th and on that day. Records for Enrique Tarrio’s phone show that while the attack on the Capitol was ongoing, he texted with Jones three times and Shroyer five times.124 Ethan Nordean’s phone records reflect that he exchanged 23 text messages with Shroyer between January 4th and 5th, and that he had one call with him on each of those days.125 Records of Joseph Biggs’s communications show that he texted with Shroyer eight times on January 4th and called him at approximately 11:15 a.m. on January 6th, while Biggs and his fellow Proud Boys were marching at and around the Capitol.126

Meanwhile, the emergency motion to keep Pattis on the trial team claimed that both he and Hull are representing Jones.

He was suspended for disclosing confidential medical records to other lawyers working on related matters for our joint client, Alex Jones;

This is insanity! You’ve got two lawyers, both facing major ethical challenges, jointly representing Biggs, Jones, and Shroyer in prosecutions aiming to demonstrate that after Trump asked him to lead a mob to the Capitol, Jones coordinated the delivery of that mob to the Proud Boys.

And Pattis’ suspension will upend the prosecutions of both Shroyer — who at least claimed he would plead guilty at the end of this month — and a guy named Doug Wyatt, who has long been pegged by researchers as one of the rioters who seemed like he might be coordinating with others.

While a lot of people were wailing that J6C was way ahead of DOJ, I was raising concerns about the things that may upend the most important prosecution to date: that Bertino transcript and attorney conflicts.

It turns out I had reserved my complaints for the stuff that, as the trial kicks off, could be the thing that sinks it.