“Poor Mr. Zebley:” Both Xitter’s Lawyers and Journalists Responding to Boilerplate Need to re-Read Mueller

I’ve stopped trying to convince Russian denialists on Xitter that they’re willfully ignorant of facts. At this point, denialists are just trolls exploiting Xitter’s algorithm to create scandal.

I try to focus my time, instead, on conspiracy theorists platformed by prominent schools of journalism.

But when others try to correct denialists on Xitter, they almost always say the denialists haven’t read the Mueller Report closely enough.

So I found it wildly ironic that Chief Judge Beryl Howell, during a period in February when Elon Musk was letting denialists like Matty Dick Pics Taibbi invade the privacy of then-Twitter’s users so he could spew conspiracy theories, Howell scolded Twitter’s lawyer George Varghese that he hadn’t read the Mueller Report closely enough.

THE COURT: You need to read the Mueller report a little bit more carefully.

The transcript of the court hearing and much of the rest of the back-up to Xitter’s attempt to stall compliance of the warrant was unsealed yesterday.

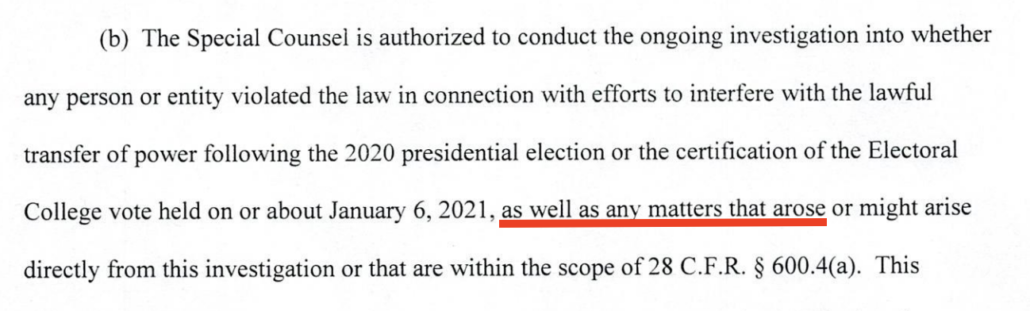

Mind you, Howell was trying to convey to Twitter’s team that there is precedent for investigating Donald J. Trump without giving him advance warning of every investigative step.

MR. VARGHESE: Yes, Your Honor. Our —- by

THE COURT: You think that for 230 orders, 2800 subpoenas, and 500 search and seizure warrants the Mueller team gave advance notice to the former President of what they were about?

MR. VARGHESE: I don’t know that, Your Honor.

THE COURT: You do not know that.

The hearing made it pretty clear that Howell is convinced that Trump will stop at nothing to obstruct criminal investigations into himself.

Howell, who knows what went into the Mueller Report as well as anyone outside the investigative team, does know that.

In fact, when she told Varghese he should have read the Mueller Report more closely, she had just pointed to private comms described in the Mueller Report — the ones where Trump told Mike Flynn to stay strong — where Trump had not gotten advance notice, as prosecutors were demanding he not get advance notice about a warrant to Twitter.

THE COURT: Because the Mueller report talks about the hundreds of Stored Communications Act — let me quote.

Let’s see.

The Mueller report states that: As part of its investigation, they issued more than 2800 subpoenas under the auspices of the grand jury in the District of Columbia.

They executed nearly 500 search and seizure warrants, obtained more than 230 orders for communications records under 18 U.S.C. Section 2703(d); and then it goes on and on and on for all of the other things they did.

And some of those communications included the former President’s private and public messages to General Flynn, encouraging him to “Stay strong,” and conveying that the President still cared about him, before he began to cooperate with the government.

So what makes Twitter think that, before the government obtained and reviewed those Trump-Flynn communications, the government provided prior notice to the former President so that he can assert executive privilege?

MR. VARGHESE: My understanding, Your Honor, is that the Mueller investigators were in contact with the White House counsel’s office about executive privilege concerns.

THE COURT: You quoted the one part that said that, and that was for testimony, testimony, where it was not covert.

Side note: Xitter’s lawyers may not have been entirely wrong about consultations with the White House counsel, even for materials obtained covertly.

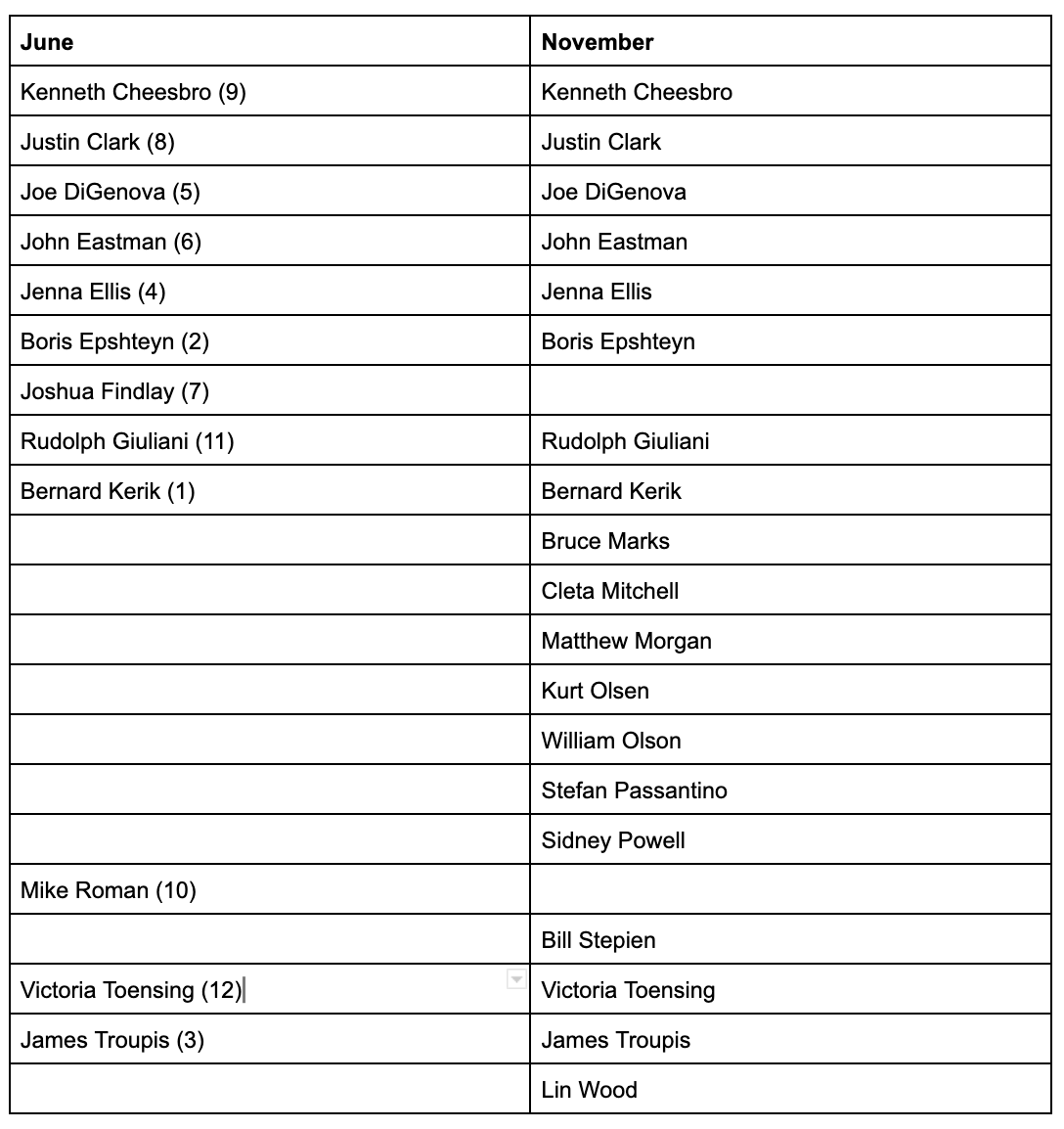

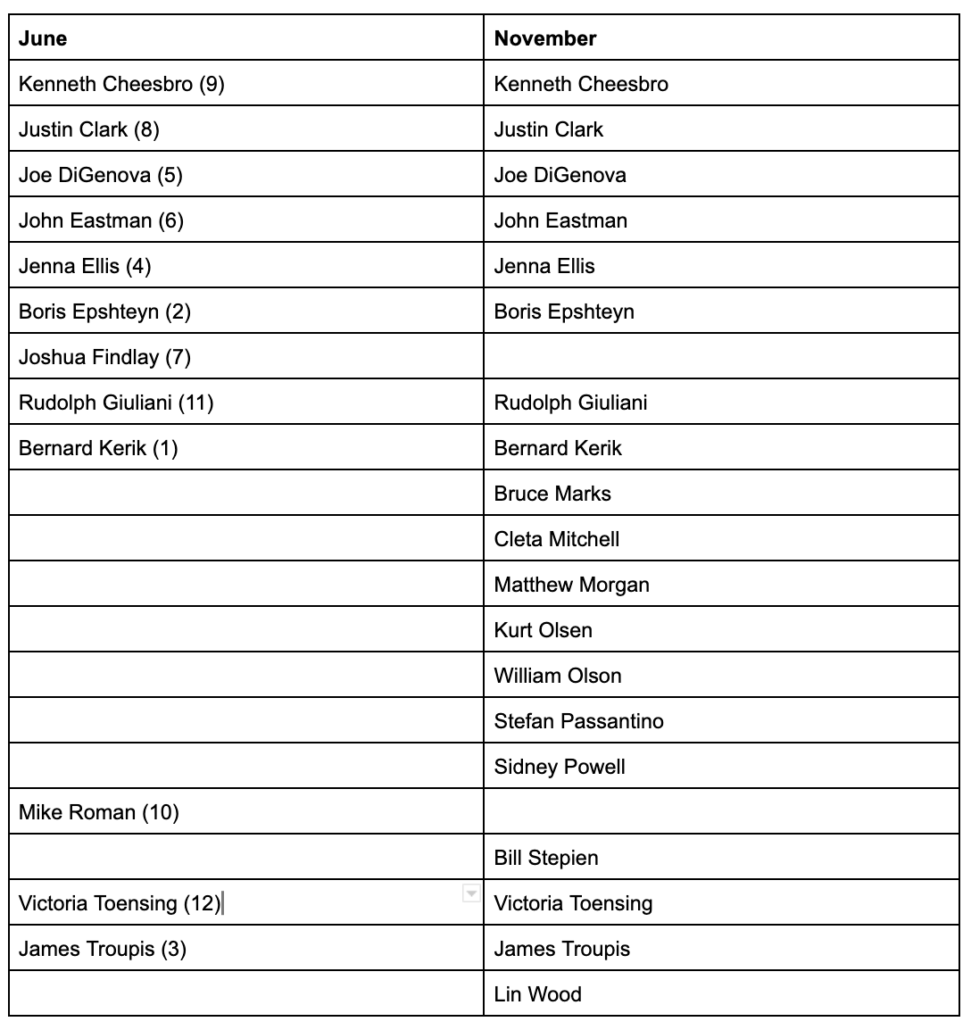

This exchange happened on February 7. Two days later there was a follow-up hearing, and WilmerHale counsel Aaron Zebley — someone who knows better than Beryl Howell what happened to the materials for which Howell approved legal process after it got handed over but before they ended up in the Report itself — filed an appearance in this challenge. He never spoke though; he showed up late, if at all, and at one point, after Twitter had presented their opening argument, Howell asked someone to check whether “poor Mr. Zebley” was standing outside a locked door waiting to get in.

THE COURT: Okay. Well, let me just —

Mr. Windom, do you want to think about that or do you want to respond?

Do you think Mr. Zebley is standing outside the locked door?

MR. HOLTZBLATT: I think there is a chance.

THE COURT: Could you check? Poor Mr. Zebley.

MR. WINDOM: Should I wait, Your Honor, or proceed?

THE COURT: Proceed. In my chambers we wait for no man.

Twitter was trying to make an argument that someone had to attend to potential Executive Privilege claims. Howell and the prosecutors nodded several times to a filter protocol addressing privilege issues, of which Twitter was ignorant. And yet Twitter was refusing to comply unless they had the opportunity to tell Donald Trump about the warrant in advance.

Beryl Howell, who was years into her second investigation of Donald Trump at this point, might be forgiven for impatience with lawyers who don’t understand how many Executive Privilege disputes she had presided over between those two investigations. They might be forgiven for their ignorance of all the resolutions of Trump’s current challenges to Executive Privilege in the January 6 investigation.

That said, Twitter’s lawyers aren’t the only ones who should have read the Mueller Report more closely. So are the journalists reporting on this.

One after another journalist (CNN, NYT, Politico, all involving journalists who covered the Mueller investigation) has mistaken DOJ’s request for data — attachment B to the warrant — as some kind of statement of what DOJ was most interested in receiving. Based on that, their stories focus on the fact that DOJ asked for or obtained DMs involving the former President.

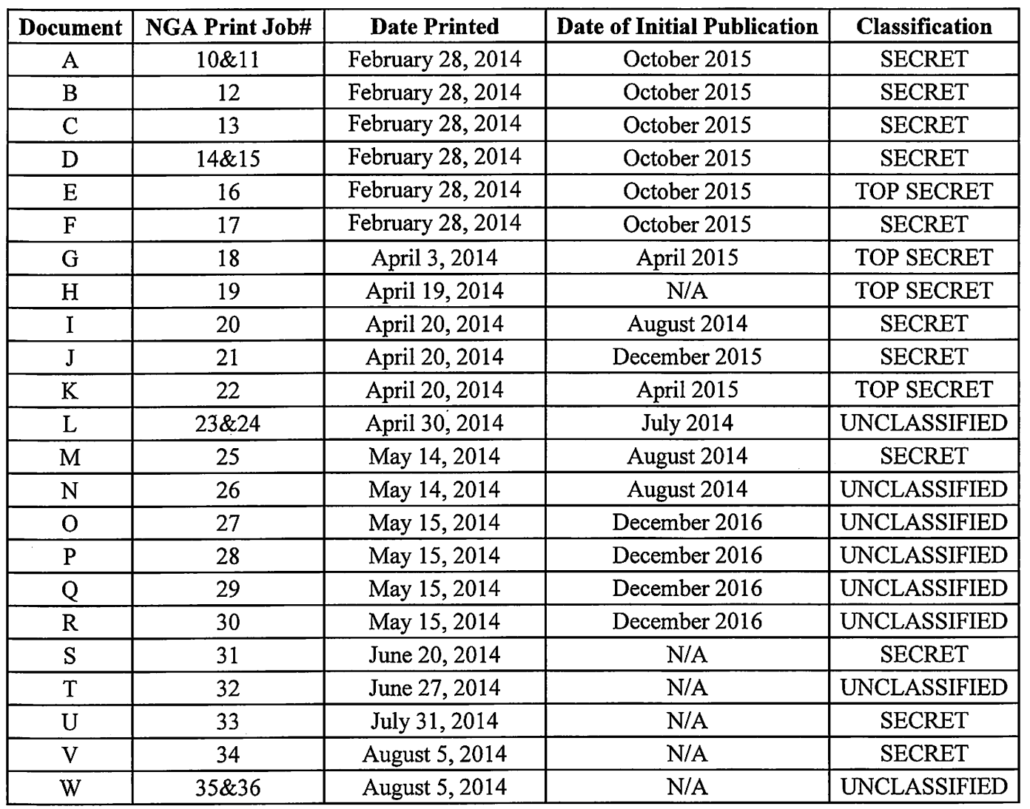

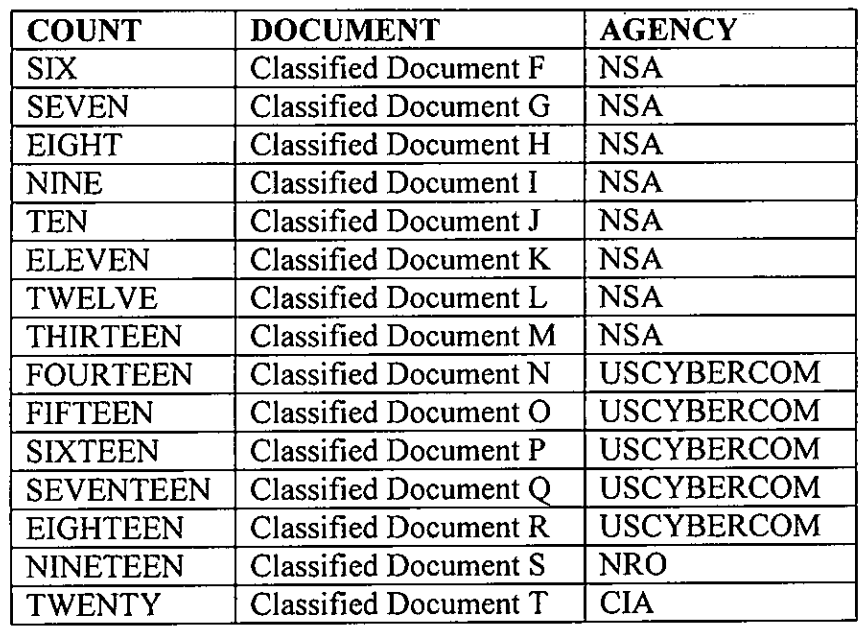

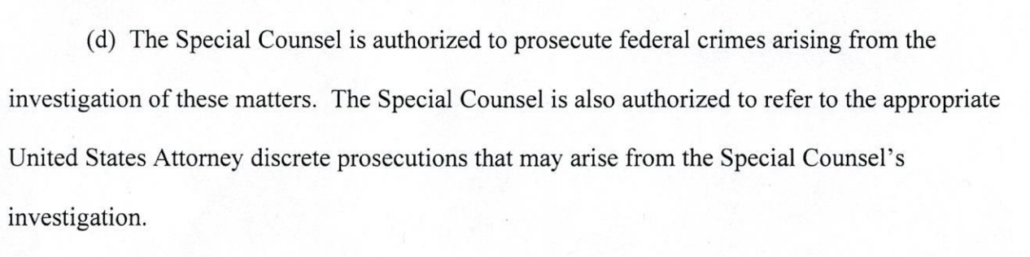

But that attachment looks to be largely boilerplate. It is not much different from warrants obtained five years ago, in the Mueller investigation, such as this one, also served on Twitter, apparently targeting Trump’s rat-fucker Roger Stone in an investigation into whether he was serving as a foreign agent of Russia, a warrant that also came with a gag, one Twitter did not contest. One main — telling — difference, is that the Trump request included standard subscription information, which Mueller’s investigators appear to have already requested; one of the items on which Twitter held up compliance, in fact, was Trump’s gender, a sure testament to obstruction within the company.

While Twitter’s services have changed significantly in the interim years, both ask for the same kind of information: DMs, drafts, deleted content, favorited content.

And for good reason!!! These warrants may well have been targeting the same kind of behavior, the kind of organized troll campaigns that exploit Twitter’s algorithms, in which users use a variety of means to obscure their identity. There is a significant likelihood these warrants were targeting precisely the same group of far right online activity, the very same people.

One of the most important Twitter users leading up to January 6, Ali Alexander, is the protégé of Roger Stone and the effort to drive attendance at January 6, Stop the Steal, was a continuation of the effort Stone started in 2016, an effort that may well have been covered by that 2018 warrant or one of the others targeting Stone’s Twitter activity.

To be sure: There are DMs in Trump’s account, though it’s not entirely clear when they date to. Without reading any of the DMs, Twitter checked to see whether the volume of data in Trump’s account indicated the presence of DMs.

MR. VARGHESE: So, Your Honor, we went back — because this was an important issue for us to compare, whether or not there were potentially confidential communications in the account, and we were able to confirm that.

THE COURT: How?

MR. VARGHESE: So, Your Honor, there was a way that we compared the size of what a storage would be for DMs empty versus the size of storage if there were DMs in the account. And we were able to determine that there was some volume in that for this account. So there are confidential communications. We don’t know the context of it, we don’t know —

THE COURT: They are direct messages. What makes you think — do you think that everything that a President says, which is generically a presidential communication, is subject to the presidential communications privilege?

MR. VARGHESE: No, Your Honor.

But Twitter’s focus on DMs arose from their frivolous basis for delaying response to the warrant — their claim that some of these DMs might be subject to a claim of Executive Privilege.

Moreover, having DMs in the account is not the same thing as a prosecutor confirming that they ultimately obtained DMs, or that any DMs were relevant to the investigation, or that DMs were one of the things they were most interested in.

I don’t doubt that’s likely! But what prosecutors asked for and what was in the larger account is not the same thing as what DOJ ultimately received and used.

And the DMs — most of them, anyway — are something that were available elsewhere. At least as represented in the dispute, NARA already has Trump’s DMs from the period (DOJ chose not to go to NARA, in part, because they wanted to avoid notice that NARA has provided to Trump along the way).

There were three more things that DOJ showed perhaps more interest in, requiring Twitter to go beyond their normal warrant response tools to comply.

The first has to do with emails to Twitter about the account, of which prosecutor Thomas Windom was most interested in emails from people on behalf of Trump.

But this information about, you know, what it is that we say that we’re most specifically interested in, I did not represent that we were most interested in communications betueen government officials and Twitter regarding the account.

We did point out that — much as Your Honor did just now — it seemed beyond comprehension that there weren’t communications regarding the account when it was suspended and terminated, but that doesn’t mean government officials at least cabined to that. It can mean campaign officials. It can be anybody acting on behalf of the user of the account, or the user of the account himself.

THE COURT: So any person regarding the account is broader than what you just said, though, Mr. Windom.

“Any person regarding the account” is quite broad. It could be all the complaints of all of the Trump supporters out in the world saying: What are you doing, Twitter?

So I take it, from what you just said, that you are interested only in =- rather than “any person,” a person who was the subscriber or user of the account or on behalf of that person regarding the account?

MR. WINDOM: Yes, ma’am. An agent thereof.

When Twitter cut Trump off in 2021, they cut off active plans for follow-up attacks. And these emails might indicate awareness of how Trump was using Twitter as a tool to foment insurrection.

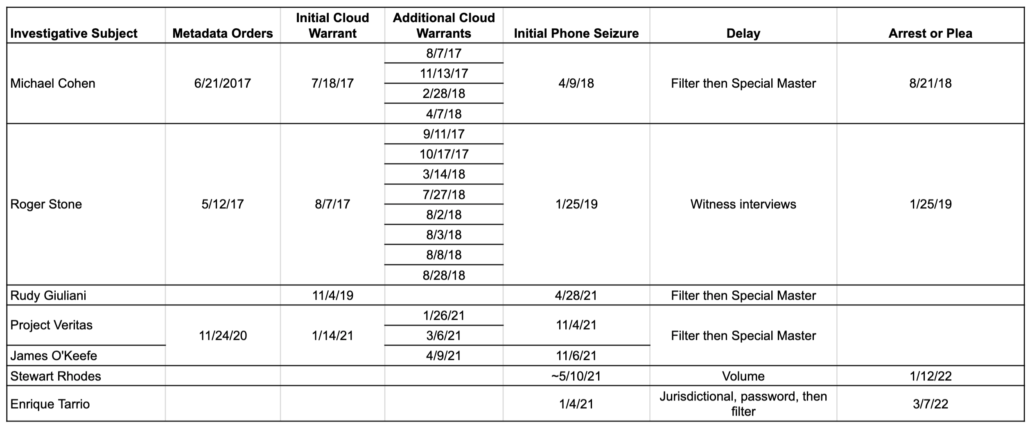

Another item on which Windom focused in the following hearing was associated accounts — other accounts the identifiers used with Trump’s accounts also use. Twitter claims they don’t have that — at least not in their law enforcement portal — and so had to collect it manually. But DOJ did ask them to produce it. (Note, the fact that Xitter doesn’t store this is one reason why they’re so bad at tracking information operation campaigns, because visibility on these kind of associations are how you discover them.)

MR. HOLTZBLATT: Well, Your Honor, we don’t — the issue, Your Honor — there isn’t a category of “associated account information”; that’s not information that Twitter stores.

What we are doing right now is manually attempting to ascertain links between accounts. But the ascertainment of links between accounts on the basis of machine, cookie, IP address, email address, or other account or device identifier is not information that Twitter possesses, it would be information that Twitter needs to create. So that’s the reason why we had not previously produced it because it’s not a category of information that we actually possess.

[snip]

MR. WINDOM: It is, as explained more fully in the warrant — but for these purposes, it is a useful tool in identifying what other accounts are being used by the same user or by the same device that has access to the account is oftentimes in any number of cases, user attribution is important. And if there are other accounts that a user is using, that is very important to the government’s investigation.

[snip]

MR. HOLTZBLATT: That’s right. If the records — if the linkage between accounts, which is what we understand this category to be referring to, is not itself a piece of information that we keep, then it’s not a business record that we would ordinarily produce.

What I understand the government to be asking is for us to analyze our data, as opposed to produce existing data. And we are trying to work with the government in that respect, but that is the reason that it is not something that — that is a different category of information.

As Windom explained, this information is critical to any attribution, but it’s also important to learning the network of people who would Tweet on Trump’s behalf, and any overlap between his account and their own (as Roger Stone’s showed in 2016).

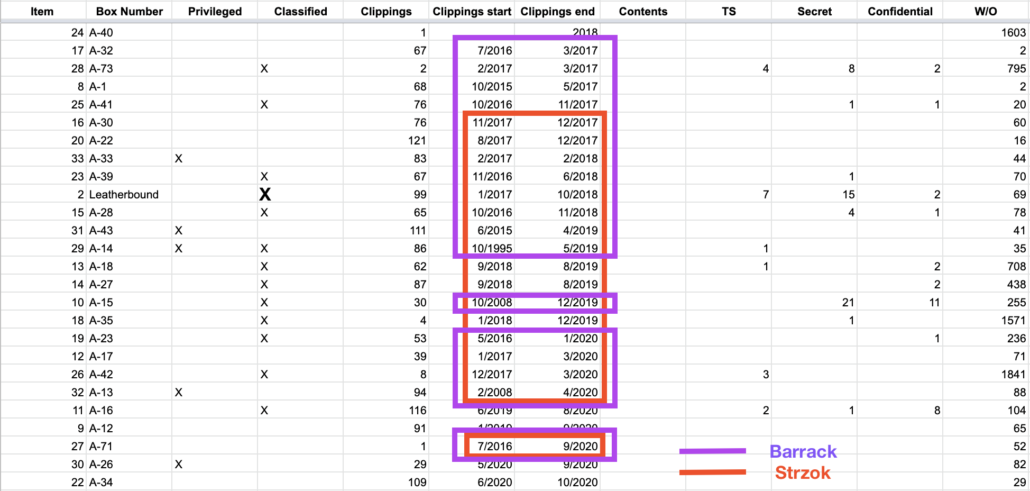

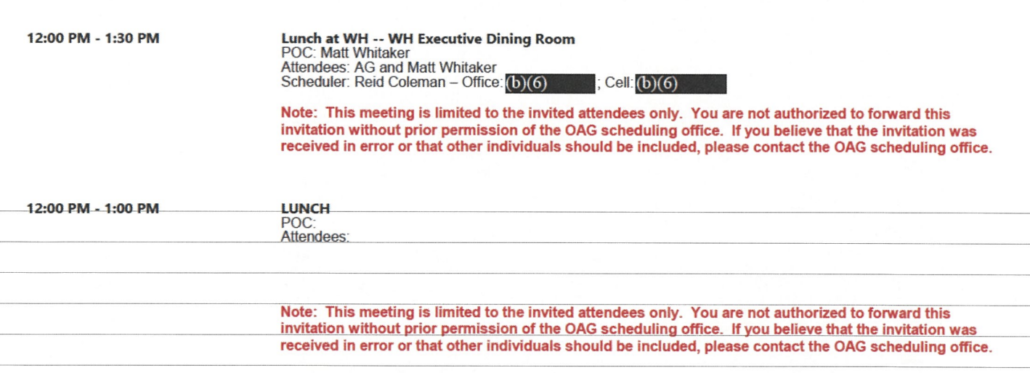

Then there’s something that remains only partially explained. For some reason — even Twitter could not figure out why — there were two preservations of Trump’s account in January 2021, before the preservation associated with this warrant. One was on January 9. The other covered January 11 and 12. And when asked, the government of course wanted the latter preservation too — and it is in the possession of Twitter, and so covered by the warrant.

MR. HOLTZBLATT: At 5 p.m. on February 7th, I think that was our day, we produced all data in this category that was in the standard production tools of Twitter.

We communicated with the government on February 8th that there were prior preservations of the subject account that are not within Twitter’s standard production tools and that would, therefore, require engineering to obtain information. And we asked the government whether it wished us to undertake that effort, and the government confirmed that it did.

And we have since then — when we produced on February 7, we indicated to the government in our production letter that there was potentially deleted data that might exist, which is what would be found in prior preservations, but that it would require additional engineering efforts.

At 2 a.m. last night, or this morning, Twitter produced additional information from those prior preservations that falls within category 2A. There are —

THE COURT: When you say “prior preservations” what are you talking about?

Prior litigation holds of some kind or that you had a stash or a cache of preserved data sitting in different places? What are you talking about?

MR. HOLTZBLATT: I am referring — with respect to this particular account, I am referring to preservations from two specific dates. There is a preservation that was made that includes the subject account covering January 3rd to 9th, 2021. There is a second preservation of this that includes this account that covers January 11 to 12, 2021.

Those are collections of data that — they are not — it’s not coterminous with the categories that would exist in the active account right now and — and that’s data that does not exist within a production environment. So it’s not data that you can just click — we have a system to just click a button and produce, which is why we indicated that further engineering efforts might be necessary.

We asked the government if they wished us to undertake those efforts. We had an engineer working through the night, after the government asked us to, to undertake those efforts. At 2 a.m. in the morning we produced additional information that came from those preservation.

There are two categories of information that — actually, I’m sorry, three categories of information that we are still working to produce because of the engineering challenges associated.

One of those categories is the list of — I am not sure this is from 2A. But I think, for purposes of coherence, it would be helpful for me to describe it now because it connects to this preservation; that is, followers — a list of followers for this account that were contained within the January 11 through 12th prior preservation. We have segregated that information. It is a complicated and large set of information. And we are unable to deliver it in the manner that we normally deliver information to law enforcement, which is to send a token.

We believe right now it would require physical media to put that information on and to hand it over to the government.

[snip]

MR. HOLTZBLATT: As I mentioned, Your Honor, there were two prior preservations, and then there is the current production tools. In two of the three of those sets, the January 3 through 9 and the current one, we have produced the tweets and related tweet information for the account.

In the January 11 to 12th prior preservation, the way that the tweet and tweet-related information is stored, it goes all the way back to 2006. We don’t have a warrant — that is contents of user communications. He don’t nave a warrant that would permit us to produce the entirety of that information. So what we have is a tool 7 that — what we refer to as a redaction (sic) tool or trimming tool. Because this is not a production environment, a human being has to go in and manually trim the information to isolate the date range. That, I think Your Honor can understand, is a laborious process, including for this particular account, given the time frame; and we need to isolate it, I think, over a three-month, four-month period, I’m sorry, Your Honor. So we are undertaking it.

Unsurprisingly, DOJ wanted to be able to compare the accounts as they existed on January 8 and January 12, 2021, because Trump’s attack was still ongoing and because people were beginning to delete data.

Trump’s DMs, if he used them or even just received them in this period, would be critically important. But Twitter was one of Trump’s most important tools in sowing an insurrection. And the data showing how he used the account, and who also used it, is as important to understanding how the tool worked as the non-public content.