The Dialectical Imagination by Martin Jay: Psychoanalysis in Critical Theory

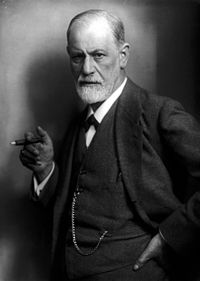

Chapter 3 of The Dialectical Imagination takes up the role of Freud’s theories in Critical Theory. A major focus is the effort to integrate Freud and Marxian analysis: Freud was pessimistic about social change, which is, of course, the goal of Marxism. That’s a problem which seems pointless. If Freud’s ideas were valuable insights, and the Frankfurt School definitely thought they were, then his bourgeois sensibility and his conservatism are irrelevant.

Chapter 3 of The Dialectical Imagination takes up the role of Freud’s theories in Critical Theory. A major focus is the effort to integrate Freud and Marxian analysis: Freud was pessimistic about social change, which is, of course, the goal of Marxism. That’s a problem which seems pointless. If Freud’s ideas were valuable insights, and the Frankfurt School definitely thought they were, then his bourgeois sensibility and his conservatism are irrelevant.

The scholars of the Institute agreed that the proletariat had failed to carry out Marx’s prediction that it would be at the vanguard of the revolution that would lead to Socialism, the social ownership of the means of production. After Germany’s loss in WWI, conditions were ripe for such an effort. There was an uprising, but the Social Democrats, then the ruling party, crushed it with the aid of the Freikorps. Leading Marxist activists, including the brilliant Rosa Luxemburg, were murdered by the Freikorps, and Marxism as a revolutionary movement collapsed. That failure had a decisive effect on most of the leading intellectuals in Germany, almost all of whom were trained in Marxian thought, including the scholars of the Frankfurt School.

One reason for the failure of the proletariat to lead the revolution is that it did not identify itself as a social class, but as individuals with their own ideas and goals. The Frankfurt School saw Freud’s ideas as a way to understand the proletariat not as a class but as a collection of individuals. Freud’s personality types showed the way to understand the proletariat not as individuals, but as groups of individuals with similar characteristics. Each personality type had its own response to the economic conditions and to the social superstructure raised above the economic stratum.

One of the most important Freudians in the Frankfurt School was Erich Fromm. According to Martin Jay, one important contribution Fromm made to Critical Theory was the use of

//… psychoanalytic mechanisms as the mediating concepts between individual and society—for example, in talking about hostility to authority in terms of Oedipal resentment of the father.

P. 91.//

There are a number of examples of this in later chapters. Perhaps one of the strangest is this:

… Adorno made the point even clearer: “However little doubt there can be regarding the African elements in jazz, it is no less certain that everything unruly in it was from the very beginning integrated into a strict scheme, that its rebellious gestures are accompanied by the tendency to blind obeisance, much like the sado-masochistic type described by analytic psychology.” P. 186.

The point of understanding the personality types and their responses to society was to strengthen individuals through properly designed educational and other programs. The Frankfurt School believed that human beings had an unlimited ability to make themselves better, more rational, more educated, and more moral. The experiences of childhood and repressive social forces could be overcome, and even genetic predispositions could be overcome to some degree.

The second main reason for introducing psychoanalysis into Critical Theory was the belief that Marxism ignored the importance of happiness as a motivating factor in people’s responses to social forces. The scholars believe that Marx was too fixated on the role of labor, and ignored the importance of pleasure.

I don’t know anything about psychology. I’ve read a couple of books by Freud and Jung but one seemed dated and the other seemed woo-woo. When I was in Law School I took a class in the Psych Department at Indiana University, of which my main memory is of a live pigeon-pecking demonstration in the entry hall; a lot of the professors seemed to be devotees of B.F. Skinner. So, that’s a caveat to the following thoughts.

The idea that we need mediating concepts between the individual and the societies individuals crreate seems sensible. Certainly we can’t hope to work our way from the individual to the society without such mediating concepts, at least not in a principled, reasoned, way.

But maybe that isn’t relevant any more. As we grow to understand the way our brains work, the way the meat functions, the way the leaky gray matter spreads hormones, neurotransmitters, and stuff, the easier it becomes to figure out ways to manipulate them directly, maybe as I discuss here and here.

Or maybe we don’t need mediating concepts in an era of big data. The claims made about Cambridge Analytica and the insights that data mining gives Target are examples of unmediated insights into individual action that open the door to direct manipulation of the individual for political or commercial purposes.

After all, mediating concepts like psychological categories were originally intended to help us understand ourselves as individuals participating in a society. They enable us to get past the barriers in our own minds to greater individuation, greater integration of the various parts of our selves into wholes, greater self-understanding. But that matters only to those who think we can make ourselves better human beings.

The people who manipulate us don’t want us to make ourselves better. They like us just like we are, and they don’t care if we as individuals become more racist, more misogynist, more authoritarian, or stupider than we already are. They take advantage of us, of our lack of self-understanding and our lack of integrated personalities, in ways we don’t notice and can’t defend against easily.

The scholars who worked on studies of prejudice and the role of authority in the family and then defined the authoritarian personality type, believed, according to Martin Jay, “…that manipulation rather than free choice was the rule in modern society”. P. 238. Here, as in many other areas, they were able to articulate clearly what we can barely see today.

![[Photo: Annie Spratt via Unsplash]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Books_AnnieSpratt-Unsplash_mod1.jpg)