The Fifteenth Amendment

After the 14th Amendment and the Reconstruction Act of 1867 were adopted the Freedmen in the former slave states had the vote. That left all the Black men in the Union and Border States and Tennessee, and that eventually was seen to be untenable. The Democrats, then the right-wing party, made universal Black suffrage an issue in the election of 1868. In The Second Founding, Eric Foner says this campaign “… witnessed some of the most overt appeals to racism in American political history.” P. 97. Grant won, but the popular vote was close, and Democrats made gains across the Union. That gave impetus to passage of an amendment to ensure the vote to all Black men.

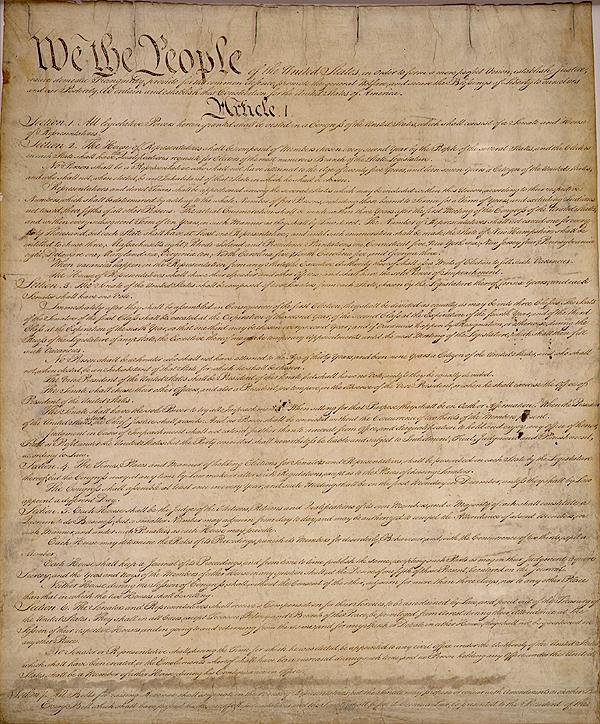

Several amendments were introduced. The main choice was whether to support universal suffrage or only for Black men. The Radical Republicans wanted a bill setting national standards for voting, a position consonant with Art. 1 § 4 of the Constitution.

But here the true level of US bigotry revealed itself. Several Union states made it clear they wouldn’t support suffrage for Germans and/or Irish Catholics (and as one of the latter, I’d say we’re pretty harmless). In the West, prejudice against Chinese immigrants was a powerful force, evoking racist comments akin to those directed at Black people. As time expired, we got the Fifteenth Amendment in its most limited form:

1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Section 2 authorizes Congress to make laws enforcing Section 1.

Section 1 is not a positive grant of suffrage to Black people. Instead, it authorizes the states to control suffrage as they see fit as long as they don’t use race as a condition. Thus it authorized Ohio to deny suffrage to German immigrants, and Rhode Island to grant suffrage only to Irish Catholic property owners; and it enabled the states to use non-racial laws to exclude Black men from the polls.

The Republicans worried that Northern states wouldn’t ratify a positive version, granting suffrage to all adult males, let alone a broader version, barring discrimination on the basis of, for example, religion. There was no question of enfranchising women or Native Americans. The final draft of the bill in each house included the right to hold office, but that was eliminated in conference, and the House version of a positive enfranchisement was dropped in favor of the Senate’s negative version.

Foner points out that legislators knew that the negative version could be gamed by the states, but assumed, or perhaps hoped, that the 14th Amendment would make that poisonous to the slave states, because discriminatory requirements would affect White people too. But that turned out to be a false hope, thanks in large part to the efforts of the Supreme Court. Also, it turns out that rich white Southerners weren’t opposed to blocking poor whites from the ballot box, or shielding them from the laws with other techniques.

The first few years after the Civil War saw the creation of a number of White vigilante groups, including the Ku Klux Klan. These groups wreaked terror on Black people across the former Confederacy, murdering and raping, pillaging and burning. The slave states did nothing to stop this hideous violence, and they did nothing for decades, leaving their Black populations to die, leave, or suffer in silence.

In the early 1870s Congress began consideration of laws to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments. Three bills, the Enforcement Acts, gave the federal government the power to punish violence against Black people, using federal courts and marshals. But they were inadequate to force the slave states to protect their Black citizens. Eventually Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which was a comprehensive effort to protect Black people from all kinds of private violence intended to deny Black people the rights guaranteed by the Reconstruction Amendments.

In the debates over all these laws, a substantial number of federal legislators called these laws violations of the principles of federalism. As we will see, the Supreme Court agreed, and struck down the new laws. Eventually because of the intransigence of the Court, the 13th Amendment was ignored, the 14th Amendment was gutted, and the 15th Amendment was barely useful.

Discussion

1. Foner integrates into his text excerpts from the debates in Congress over the Amendments, and from newspaper articles, giving a flavor of the rhetoric and feelings of the speakers and perhaps those of the elites. Here’s a nice example:

“Tell me nothing of a constitution,” declared Joseph H. Rainey, a black congressman from South Carolina whose father, a successful barber, had purchased the family’s freedom in the 1840s, “which fails to shelter beneath its rightful power the people of a country.” By the people who needed protection, Rainey made clear, he meant not only blacks but also white Republicans in the South. If the Constitution, he added, was unable to “afford security to life, liberty, and property,” it should be “set aside.” P. 119. Fn omitted.

The other side was equally direct and eloquent:

In the debate over the Ku Klux Klan Act, Carl Schurz, representing Missouri in the Senate, said that preserving intact the tradition of local self-government was even more important than “the high duty to protect the citizens of the republic in their rights.” Lyman Trumbull complained that the Ku Klux Klan Act would “change the character of the government.” P. 120.

These anecdotes make this book a real pleasure to read. They remind us that our ancestors were thoughtful and forthright, or even bombastic, whether or not we agree with their sentiments today. I do not think the same of the former members of the Supreme Court, whose opinions are very difficult to read, and reek of unwillingness to deal with the Reconstruction Amendments and the facts of the cases they decided.

2. These quotes illustrate the issues around federalism. Both of the books in this series claim that the Reconstruction Amendments changed the nature of the US governing structure, by giving the federal government the power to protect the Constitutionally guaranteed rights of its citizens from private parties and from the states themselves. As we know, this hasn’t exactly worked out in practice. Even today and even in the supposedly less-racist cities and states, police and private citizens violate the civil rights of citizens, use all sorts of tricks to strip the power of minority voters, and treat citizens differently. SCOTUS is fine with that, as we saw in the ridiculous advisory opinion in 303 Creative.

We need a discussion of the purposes of federalism in this country, and we need to discuss publicly what it means to be an American citizen as opposed to a citizen of Mississippi or Minnesota. Why is it that our fundamental rights arise from citizenship in Mississippi or Minnesota, instead of from our national document, the Constitution? I’m pretty sure most uses of federalism are to discriminate against or punish people the benighted legislature doesn’t like.

3. Constitutional amendments and laws don’t change people’s minds. The Civil War didn’t really change any minds. Is it possible that elites, including supreme courts can’t get out of their own privileged pasts?