Citizenship

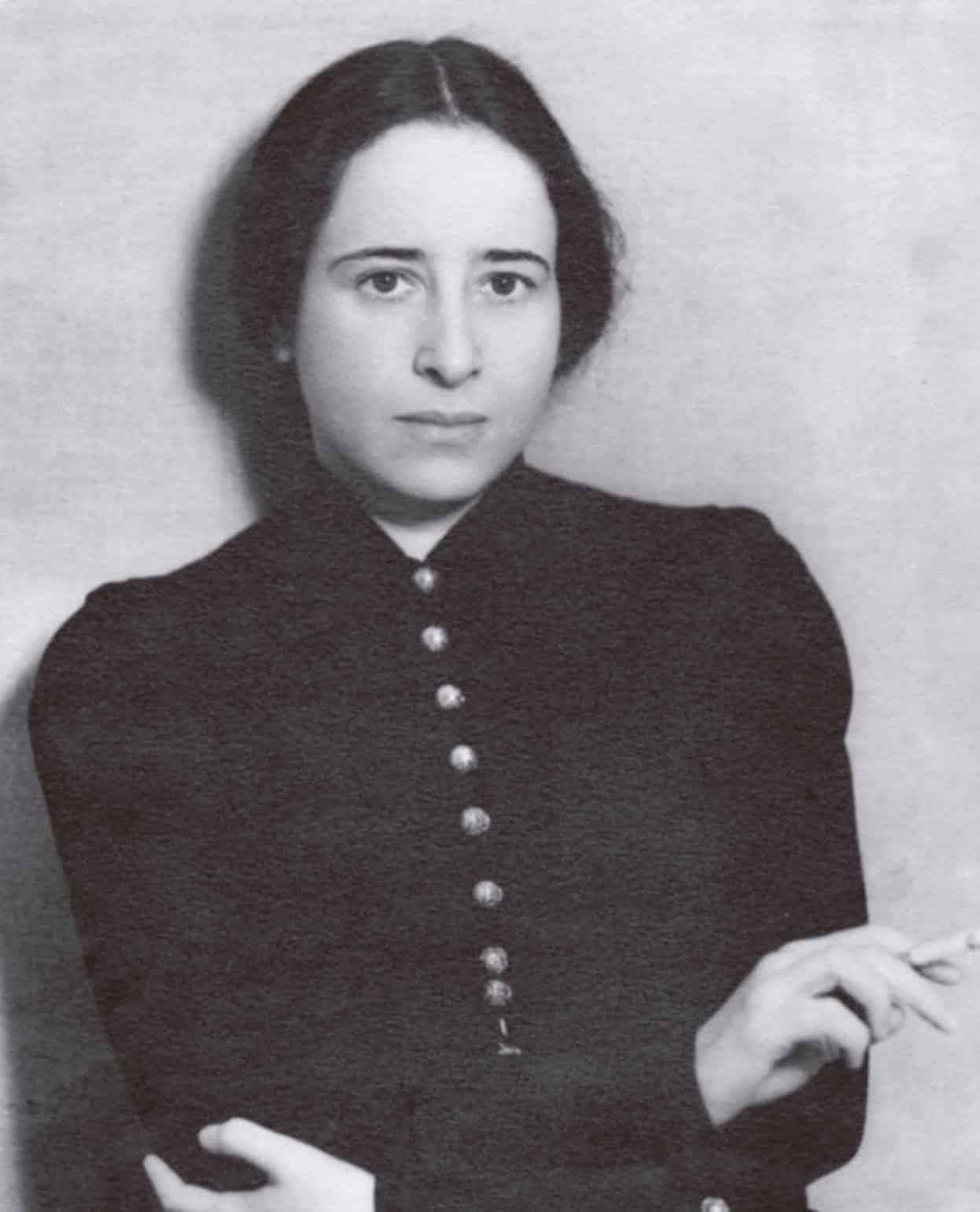

In the last part of Chapter 9 of The Origins Of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt explains her ideas about citizenship as a crucial part of human nature. Arendt was a scholar of the ancient Greeks, and it shows in this section.

A place in the world

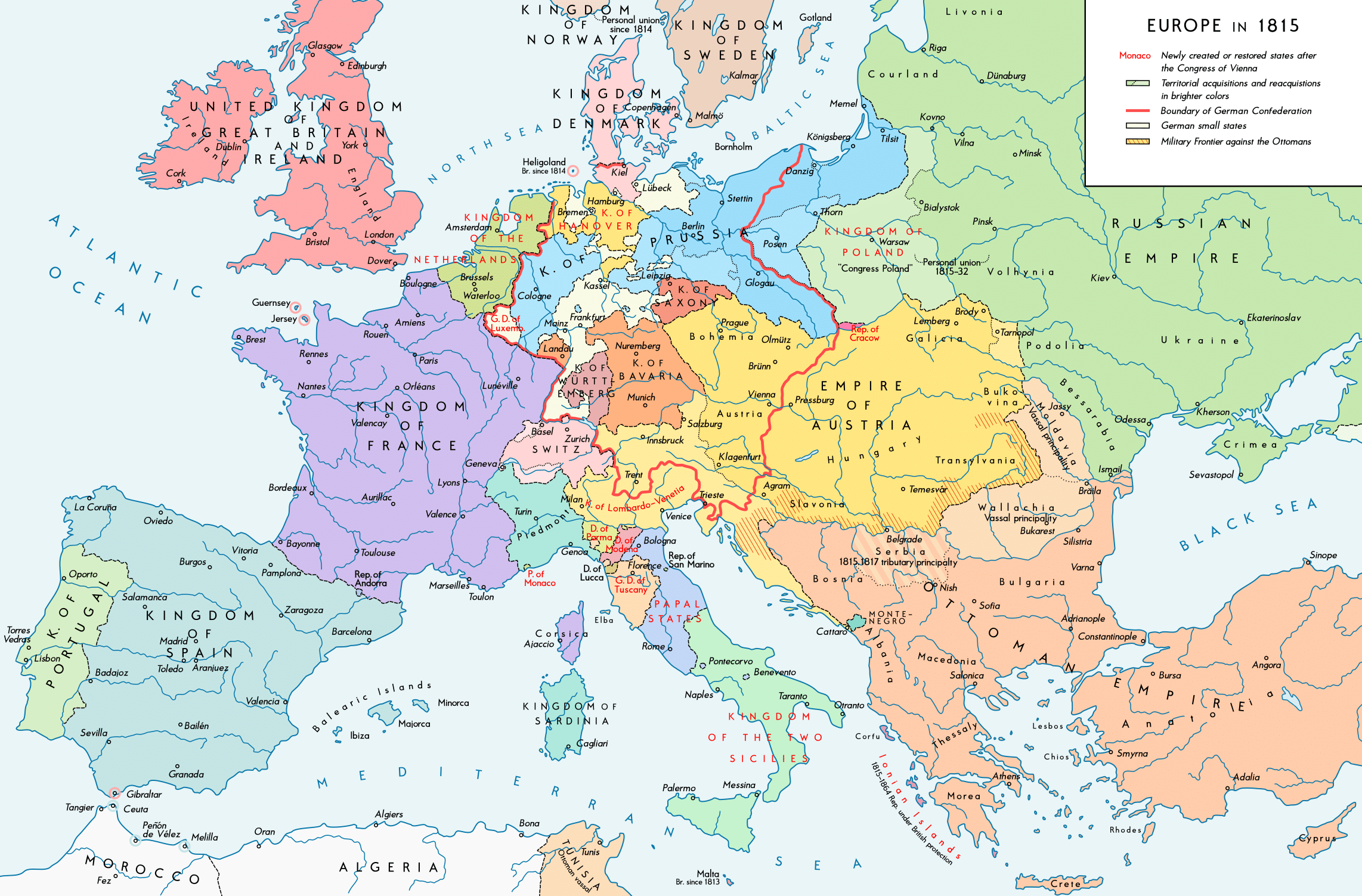

In prior posts I looked at statelessness arising from the enormous European migrations during and after WWI. Millions of people were deprived of citizenship in their own nations, or worse, their nations disappeared, leaving them not even subject to deportation. Having no state to protect their rights, they were in effect deprived of all human rights.

The fundamental deprivation of human rights is manifested first and above all in the deprivation of a place in the world which makes opinions significant and actions effective. Something much more fundamental than freedom and justice, which are rights of citizens, is at stake when … one is placed in a situation where, unless he commits a crime, his treatment by others does not depend on what he does or does not do. P. 296.

In Arendt’s view, this is the nub of the disaster facing stateless people. They continue to exist, but it doesn’t matter what they say or think or do. They are alive, but they are useless, superfluous. Their treatment by others, the way they are dealt with by the state, has nothing to do with their opinions or actions.

This right, the right to participate in the life of a community, was thought to inhere in people. It has roots deep in human history and far back into pre-history. In earlier times, groups of people driven out of a community might be taken in by another group, or they might be able to live on their own, as shown in the delightful story of the Kimmeri as told by Herodotus in the Histories, Vol. 1, Book IV, ¶ 11 (set out below).

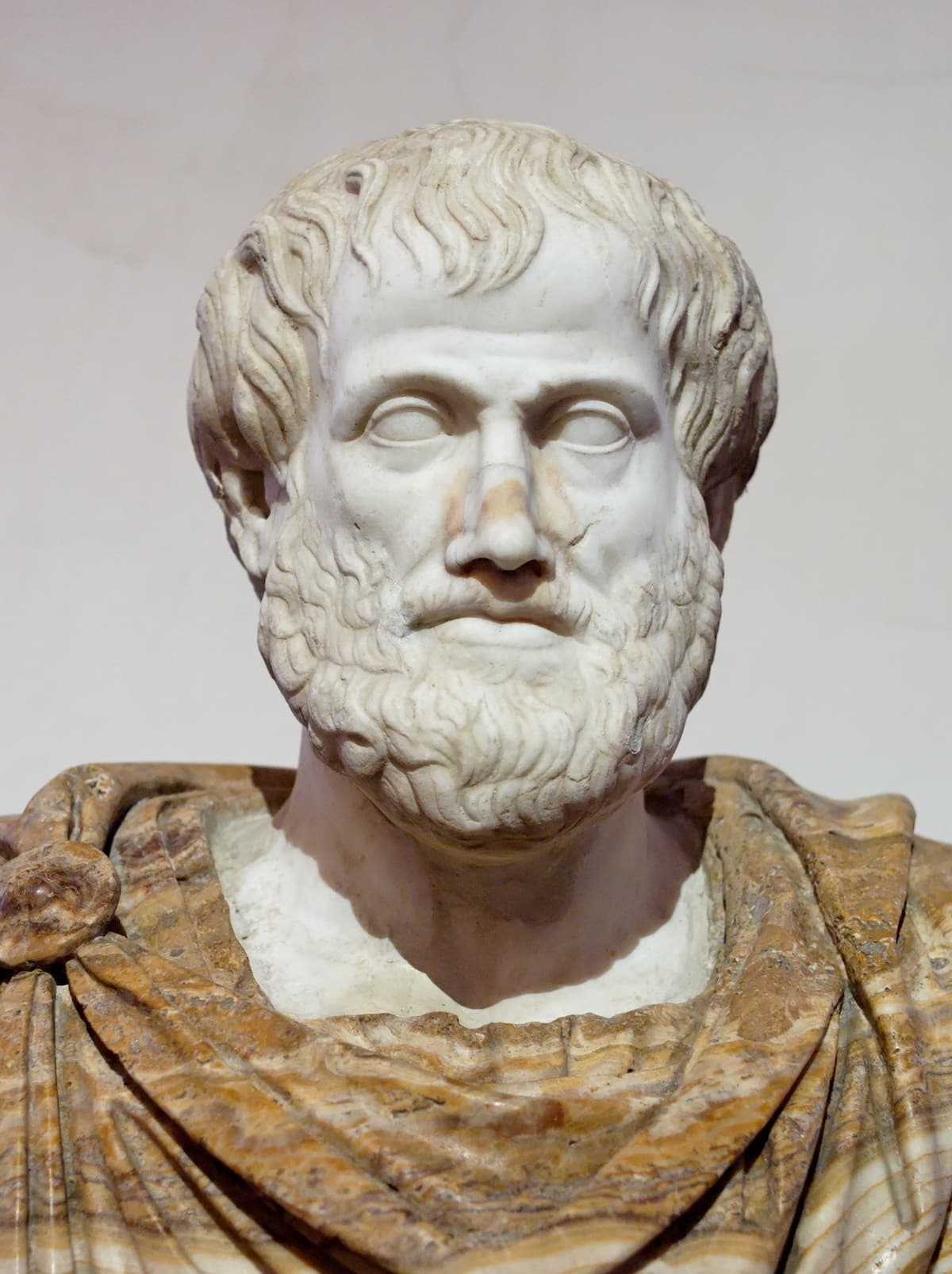

Arendt says that at least since Aristotle, the ability to speak and act was defined as the nature of human beings, and it was Aristotle who called humans “political animals”. Aristotle saw that these were not characteristics of slaves, and therefore slaves were not human. Arendt notes that even slaves had a place in society, and their labor was a valuable asset that remained in their control to some extent. But that wasn’t true of the stateless people. They had no place in society other than whatever charity might hand them.

In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson says that the Colonies are entitled to “the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them”. In a passage based on the writings of Edmond Burke about the French Revolution, Arendt asks how we could possibly think a universe which showed no sign of either laws or rights implied anything for us humans.

A return to nationalism

Beginning at page 299, lay out Arendt offers her thought on the best way forward. The argument is multi-layered and not quite clear to me. As I read it, she thinks the solution can’t come from outside us, in history, nature, or from a common humanity. She thinks the solution lies in the laws of each nation. She thinks we are capable of creating laws that define and protect the rights we are willing to extend to each other, nation by nation.

She points to Burke’s rejection of the French Rights of Man And The Citizen. Burke calls these rights “abstractions”, and they are, just as Jefferson’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are abstractions. We can’t govern ourselves with abstractions, we can’t protect abstractions, and we can’t even agree on the meaning of these abstractions because in the end, the meaning is dependent on the context.

According to Burke, the rights which we enjoy spring “from within the nation,” so that neither natural law, nor divine command, nor any concept of mankind such as Robespierre’s “human race,” “the sovereign of the earth,” are needed as a source of law. P. 299, fn. omitted.

She says:

We are not born equal; we become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights. P. 301.

She offers a pragmatic justification: the abstractions failed the stateless, but the protection of rights by the state worked.

She offers more abstract justifications, based on the notion that we as humans deeply want to be part of societies, and to contribute our ideas and our labor to the general good. She notes that the ancient Greeks,distinguished between the public and private spaces in communal life. Private space is based on individuality and difference. Public life is based on equality of participation and recognition, and this is the sphere of life in which we all want to participate.

Discussion

1. The strength of our rights is based on our ability to work together to achieve a good life. Successful nation-states work to diminish or eliminate the kinds of differences, arising from the private space, that make working together difficult or impossible. Religion is often one of those intractable problems. In the US, the idea was to keep religion our of the public sphere to the maximum extent possible. We put it in the Constitution. In the 14th Amendment we said we wouldn’t deny rights to people on acount of race. Today we see how eroding that principles divides us, and makes solutions to common problems impossible.

2. I started this series saying that we humans create the rights of Man. Our ideas about how to live together have evolved over millennia as our human ancestors worked out ways of living together. Arendt says that the universe does not seem to recognize the categories of rights and laws (p. 298) so that we, who are part of nature, can’t deduce rights and laws about ourselves.

I don’t agree with that. We can and do deduce the actual laws governing nature, even laws we don’t understand, like quantum theory and dark matter. In a similar way, we can deduce laws that will give us the best chance of flourishing. This has already happened in the past when civilizations moved away from animism and paganism.

This transformation occurred independently in four different regions during the Axial Age, a pivotal period lasting from 900 B.C. to 200 B.C., producing Taoism and Confucianism in China, Buddhism and Hinduism in India, Judaism in the Middle East and philosophic rationalism in Greece.

This quote is from a review of a book by Karen Armstrong, The Great Transformation: The Beginning Of Our Religious Traditions, in the New York Times. As I recall this book, Armstrong sees a common strain in these religious traditions that can be summarized as forms of the Golden Rule.

Perhaps it was this common strain that led Enlightenment thinkers like Jefferson to the idea of natural rights, or universal rights recognized by everyone. Those universal rights were, of course, never actually universal: autocratic leaders found multiple reasons to deny them to groups of people.

Each of these great religions co-evolved with a different social structure. Those different structures have lasted several thousand years of material and intellectual changes. Are there signs that those structures are morphing towards greater commonality, at least among the wealthier citizens with access to the world-wide communications platforms? How would rights work in nations with a large number of people who have moved away from traditional structures while another large number remain committed to an older structure? Is there enough commonality among citizens to hold nations together?

========

The story of the Kimmerians, as told by Herodotus:

There is however also another story, which is as follows, and to this I am most inclined myself. It is to the effect that the nomad Scythians dwelling in Asia, being hard pressed in war by the Massagetai, left their abode and crossing the river Araxes came towards the Kimmerian land (for the land which now is occupied by the Scythians is said to have been in former times the land of the Kimmerians); and the Kimmerians, when the Scythians were coming against them, took counsel together, seeing that a great host was coming to fight against them; and it proved that their opinions were divided, both opinions being vehemently maintained, but the better being that of their kings: for the opinion of the people was that it was necessary to depart and that they ought not to run the risk of fighting against so many, 14 but that of the kings was to fight for their land with those who came against them: and as neither the people were willing by means to agree to the counsel of the kings nor the kings to that of the people, the people planned to depart without fighting and to deliver up the land to the invaders, while the kings resolved to die and to be laid in their own land, and not to flee with the mass of the people, considering the many goods of fortune which they had enjoyed, and the many evils which it might be supposed would come upon them, if they fled from their native land. Having resolved upon this, they parted into two bodies, and making their numbers equal they fought with one another: and when these had all been killed by one another’s hands, then the people of the Kimmerians buried them by the bank of the river Tyras (where their burial-place is still to be seen), and having buried them, then they made their way out from the land, and the Scythians when they came upon it found the land deserted of its inhabitants

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt#/media/File:Hannah_Arendt_1933.jpg

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt#/media/File:Hannah_Arendt_1933.jpg