Three Republican Senators — Chuck Grassley, Ron Johnson, and Lindsey Graham — have gotten Bill Barr and Ric Grenell to declassify a bunch of things pertaining to Carter Page’s surveillance. While the materials have sent the frothy right into a frenzy again, the materials are actually far more interesting, ambiguous, and at times, damning to Trump’s narrative than the right wing stenographers have made out. This post will look at a series of footnotes to the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page that have been declassified. I’m going to look at allegations about Russian knowledge of Steele’s project in July 2016 and evidence the Michael Cohen claims were disinformation in more detailed in a follow-up; both revelations may hurt Trump’s narrative more than help it, contrary to claims by the frothers.

The purge at ODNI enabled this declassification to occur

Before I get into what the declassified footnotes show, it’s important to understand Grenell’s role in it. In his statement releasing the full set of declassified footnotes, Grassley thanked both Bill Barr and Grenell. In Ron Johnson’s WSJ op-ed feeding the ignorant frenzy about the footnotes, he described how he and Grassley had to keep pressing for their declassification until Grenell made it happen.

My colleague Sen. Chuck Grassley and I began pressing Attorney General William Barr, and eventually acting Director of National Intelligence Richard Grenell, for full declassification of these footnotes. That’s why they’re now public.

In Grenell’s letter providing the footnotes (which very notably did not come as a re-released IG Report, as a prior declassification had), he explained that,

[H]aving consulted the heads of the relevant Intelligence Community elements, I have declassified the enclosed footnotes. I consulted with the Attorney General William Barr, and he has authorized the ODNI to say that he concurs in the declassification insofar as it relates to DOJ equities.

Grenell, of course, is doing the DNI job part time, on top of his full-time job as Ambassador to Germany and his day job of trolling dishonestly on the Internet. So the declassification might be better understood as the work of Kash Patel, who, while he was a staffer on the House Intelligence Committee, started this declassification project and also served as a gatekeeper to ensure GOP Congressmen did not get accurate information on Russia. While he was on the National Security Council, Patel ensured that Trump did not get accurate information on Ukraine. And the release comes just days after Trump got rid of the last Senate confirmed person at ODNI, something that Adam Schiff has raised concerns about.

Don’t get me wrong: I support these declassifications and with a very few exceptions in these footnotes, don’t think embarrassing stuff got hidden because Grenell was involved (I have a different opinion about how stuff was declassified for Lindsey, even while I’m thrilled to have the precedent for entire FISA applications being released). Some of the most interesting declassifications confirm small details about FISA that have long been known, but have been impossible to prove since DOJ guarded that confirmation so assiduously. But it is crystal clear this declassification happened as a result of dismantling longtime Intelligence Community protections, for better and worse.

The footnotes show FBI and FISA worked like it normally does and so did the Russians

As noted, Grenell didn’t effectuate this declassification by having DOJ IG release an updated version of the report, but instead by releasing all the redacted footnotes, with any newly declassified information unmarked, out of context. Not only does that obscure a few key ones that weren’t further declassified or had already been declassified, but it makes it harder to understand what they mean in context. I’ll treat each of them in turn, italicizing the newly disclosed information, if any.

17: The Brits let Steele cooperate

The OIG also interviewed witnesses who were not current or former Department employees regarding their interactions with the FBI on matters falling with the scope of this review, including Christopher Steele and employees of other U.S. government agencies. 17

17 According to Steele, his cooperation with our investigation was done with the consent of his government.

The fact that Steele emphasized this — and the delayed timing of Steele’s cooperation — suggest that the UK wanted to make clear that they were willing to expose their own intelligence weaknesses to cooperate with something Trump had put significant stock in.

21, 354: DOJ IG considered some of the FISA collection on Page irrelevant to this review

We also received and reviewed more than one million documents that were in the Department’s and FBI’s possession. Among these were electronic communications of Department and FBI employees and documents from the Crossfire Hurricane investigation, including interview reports (FD-302s and Electronic Communications or ECs), contemporaneous notes from agents, analysts, and supervisors involved in case-related meetings, documents describing and analyzing Steele’s reporting and information obtained through FISA coverage on Carter Page, and draft and final versions of materials used to prepare the FISA applications and renewals filed with the FISC. 21

21 We did not review the entirety of FISA collections obtained through FISA surveillance and physical searches targeting Carter Page. We reviewed only those documents collected under FISA authority that were pertinent to our review.

[snip]

Emails and other communications reflect that in the first week of surveillance on Carter Page [redacted], following the granting [redacted] application -· in the October 2016, the Crossfire Hurricane team collected [redacted] 354

354 We did not review the entirety of FISA collections obtained through FISA surveillance and physical searches targeting Carter Page. We reviewed only those documents collected under FISA authority that were pertinent to our review.

These declassifications reveals two phrases — “collections,” and “physical searches” — that have long been treated as classified (though they appear elsewhere in the report, usually by accident). The import of these phrases, especially “physical search,” which actually includes “stored communications,” is why they’ve been hidden in the past.

While the meaning of these footnote was always clear, the import of it (that is, what DOJ IG would considered irrelevant to their review) remains unclear, especially given Michael Horowitz’s public questions about whether the collection was ever useful.

That’s especially true given how FISA surveillance was integrated into later Carter Page applications. The applications Lindsey Graham released makes it clear there was a good deal (indeed, it clearly corroborated concerns about Page’s hope to open a pro-Russian think tank as well as sustained questions about whom Page met with in Russia — though that’s partly because he oversold his ties there to the campaign). The redactions, however, were just hiding FISA vocabulary that had previously been hidden.

61 and 63: How the FBI decides to make someone an informant

The CHSPG recognizes that the decision to open an individual as a CHS will not only forever affect the life of that individual, but that the FBI will also be viewed, fairly or unfairly, in light of the conduct or misconduct of that individual. 59 Accordingly, the CHSPG identifies criteria that handling a ents must consider when assessing the risks associated with the potential CHS. [redacted]60 These risks must be weighed against the benefits associated with use of the potential CHS. 61

Once a CHS has been evaluated and recruited, the CHSPG does not allow for tasking until after the CHS has been approved for opening by an FBI SSA; the required approvals for a specific tasking have been granted; and the CHS has met with the co-handling agent assigned to his or her file, who has the same duties, responsibilities, and file access as the handling agent. 62 The CHSPG requires additional supervisory approval by a Special Agent in Charge (SAC) and review by a Chief Division Counsel CDC to open CHSs that are “sensitive” sources, [redacted]

61 Criteria used by agents and analysts to weigh the risks and benefits are: (1) access [redacted] (2) suitability: [redacted] (3) susceptibility: [redacted] (4) accessibility: [redacted] (5) security; [redacted]

62 CHSPG § 3.1.

63 CHSPG Section 3.5.1.1 Special approval and notification requirements also are necessary for CHS operations in extraterritorial jurisdiction, such as tasking a CHS to contact the subject of an investigation who is located in a foreign country. The requirements and notifications differ, for example, depending on whether the CHS operating is a national security extraterritorial operation or a criminal extraterritorial operation involving a sensitive circumstance. Approval from an FBI Assistant Director is necessary for national security extraterritorial operations, [redacted]

[snip]

Under the CHSPG, which vests SSAs with daily oversight responsibility for CHSs in routine investigations, approval at the SSA level was sufficient. 525 The only relevant exception for the Crossfire Hurricane investigation were counterintelligence CHS extraterritorial operations, which required approval by an FBI Assistant Director, and which we found received approval by Priestap. 526

526 As described in Chapter Two, the special approval and notification requirements for CHS operations in extraterritorial jurisdiction differ, for example, depending on whether the CHS operation is a national security extraterritorial operation or a criminal extraterritorial operation involving a sensitive circumstance. Approval from an FBI Assistant Director is necessary for national security extraterritorial operations, CHSPG Sections 19.2, 19.3.3. Because the Crossfire Hurricane investigation at the outset was a national security investigation, the extraterritorial CHS operations in the case required Assistant Director approval.

These sections reveal details of the FBI’s rules on informants and the special approvals needed in some cases. This information had already been liberated by Terry Albury (see PDF 25 and 31ff) for the earlier sections that remain redacted (which is a testament to the novelty of this declassification, since he’s in prison for having released it). They’re interesting in the case of Carter Page because there was some dispute about using Steele (to say nothing of the disagreement between Steele and the FBI about what their relationship really entailed).

Apparently, Bill Priestap had to give approval for overseas use of informants (and this must extend to Stefan Halper), not because the investigation was sensitive, but because it was a national security investigation.

164, 464, 484: Joseph Mifsud was neither a CIA asset nor had CIA collected on him

During one of these meetings, Papadopoulos reportedly “suggested” to an FFG official that the Trump campaign “received some kind of a suggestion from Russia” that it could assist the campaign by anonymously releasing derogatory information about presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. 164

164 During October 25, 2018 testimony before the House Judiciary and House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, Papadopoulos stated that the source of the information he shared with the FFG official was a professor from London, Joseph Mifsud. Papadopoulos testified that Mifsud provided him with information about the Russians possessing “dirt” on Hilary Clinton. Papadopoulos raised the possibility during his Congressional testimony that Mifsud might have been “working with the FBI and this was some sort of operation” to entrap Papadopoulos. As discussed in Chapter Ten of this report, the OIG searched the FBI’s database of Confidential Human Sources (CHS), and did not find any records indicating that Mifsud was an FBI CHS, or that Mifsud’s discussions with Papadopoulos were part of any FBI operation. In Chapter Ten, we also note that the FBI requested information on Mifsud from another U.S. government agency, and received a response from the agency indicating that Mifsud had no relationship with the agency and the agency had no derogatory information on Mifsud.

(U) We refer to Joseph Mifsud by name in this report because the Department publicly revealed Mifsud’s identity in The Special Counsel’s Report (public version). According to The Special Counsel’s Report, Papadopoulos first met Mifsud in March 2016, after Papadopoulos had already learned that he would be serving as a foreign policy advisor for the Trump campaign. According to The Special Counsel’s Report, Mifsud only showed interest in Papadopoulos after learning of Papadopoulos’s role in the campaign, and told Papadopoulos about the Russians possessing “dirt” on then candidate Clinton in late April 2016. The Special Counsel found that Papadopoulos lied to the FBI about the timing of his discussions with Mifsud, as well as the nature and extent of his communications with Mifsud. The Special Counsel charged Papadopoulos under Title 18 U.S.C. § 1001 with making false statements. Papadopoulos pled guilty and was sentenced to 14 days in prison. See The Special Counsel’s Report, Vol. 1, at 192‐94

[snip]

The FBI’s Delta files contain no evidence that Mifsud has ever acted as an FBI CHS,463 and none of the witnesses we interviewed or documents we reviewed had any information to support such an allegation. 464

464 The FBI also requested information on Mifsud from another U.S. government agency, and received a response from that agency indicating that Mifsud had no relationship with that agency.

[snip]

In Crossfire Hurricane, the “articulable factual basis” set forth in the opening EC was the FFG information received from an FBI Legal Attache stating that Papadopoulos had suggested during a meeting in May 2016 with officials from a “trusted foreign partner” that the Trump team had received some kind of suggestion from Russia that it could assist by releasing information damaging to candidate Clinton and President Obama. 484

484 Papadopoulos has stated that the source of the information he shared with the FFG was a professor from London, Joseph Mifsud, and has raised the possibility that Mifsud may have been working with the FBI. As described in Chapter Ten of this report, the OIG searched the FBI’s database of Confidential Human Sources (CHSs) and did not find any records indicating that Mifsud was an FBI CHS, or that Mifsud’s discussions with Papadopoulos were part of any FBI operation. The FBI also requested information on Mifsud from another U.S. government agency and received no information indicating that Mifsud had a relationship with that agency or that the agency had any derogatory information concerning Mifsud.

These declassifications debunk something George Papadopoulos has long claimed: that Joseph Mifsud was part of a Deep State plot run by either the FBI or CIA. The FBI asked CIA if they knew anything about him but did not.

166: How the FBI got involved

The Legat told us he was not provided any other information about the meetings between the FFG and Papadopoulos. 166

166 According to Legat, the senior intelligence official stated at the meeting with the USG official that the FFG information “sounds like an FBI matter.”

This explains how, after Australia passed the Papadopoulos tip to State, State called in both the FBI Legal Attaché in London and a senior intelligence officer — probably Gina Haspel, who at the time was London Station Chief — to explain the tip, after which the SIO said FBI should deal with it. Again, it undermines part of the claims of a Deep State coup.

205: Proof Steele should have known FBI considered him an informant, not a consultant

Steele stated that he never recalled being told that he was a CHS and that he never would have accepted such an arrangement, despite the fact that he signed FBI admonishment and payment paperwork indicating that he was an FBI CHS. 205

205 During his time as an FBI CHS, Steele received a total of $95,000 from the FBI. We reviewed the FBI paperwork for those payments, each of which required Steele’s Signed acknowledgement. On each document, of which there were eight, was the caption “CHS Payment” and “CHS’s Payment Name.” A signature page was missing for one of the payments.

This passage was redacted to hide the fact that when the FBI pays informants they don’t do so under their own name. The passage as a whole provides reason why Steele should have known, contrary to his claims, that FBI treated him bureaucratically as an informant. The fact he had a payment name may or may not strengthen that proof.

208: Oligarchs spent much of 2015 trying to meet the FBI through Steele

In our review of Steele’s CHS file, other pertinent documents, and interviews with Handling Agent 1, Ohr, and Steele, we observed that Steele had multiple contacts with representatives of Russian oligarchs with connections to Russian Intelligence Services (RIS) and senior Kremlin officials. 208

208 (U) A 2015 report concerning oligarchs written by the FBI’s Transnational Organized Crime Intelligence Unit (TOCIU) noted that from January through May 2015, 10 Eurasian oligarchs sought meetings with the FBI, and 5 of these had their intermediaries contact Steele. The report noted that Steele’s contact with 5 Russian oligarchs in a short period of time was unusual and recommended that a validation review be completed on Steele because of this activity. The FBI’s Validation Management Unit did not perform such an assessment on Steele until early 2017 after, as described in Chapter Six, the Crossfire Hurricane team requested an assessment in the context of Steele’s election reporting. Handling Agent 1 told us he had seen the TOCIU report and was not concerned about its findings concerning Steele because he was aware of Steele’s outreach efforts to Russian oligarchs. We found that the TOCIU report was not included in Steele’s Delta file. Handling Agent 1 said that he found preparation of the TOCIU report “curious” because he believed that TOCIU was aware of Steele’s outreach efforts and fully supported them.

The fact that Steele was a liaison between the US government and Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs was not secret. Indeed the sections on Bruce Ohr, as well as Ohr’s declassified 302s, make that clear. What’s most interesting about this (prior) redaction is that, while marked as unclassified, the footnote was redacted. While it’s damning that this was not in Steele’s Delta file, that it had been but is not now redacted may say more about investigations into Ohr and Oleg Deripaska and others, than it does about Steele (meaning they’re no longer protecting those investigations).

210 and 211: Deripaska’s contemporaneous knowledge of the Steele dossier

Ohr told the OIG that, based on information that Steele told him about Russian Oligarch 1, such as when Russian Oligarch 1 would be visiting the United States or applying for a visa, and based on Steele at times seeming to be speaking on Russian Oligarch l’s behalf, Ohr said he had the impression that Russian Oligarch 1 was a client of Steele. 210 We asked Steele about whether he had a relationship with Russian Oligarch 1. Steele stated that he did not have a relationship and indicated that he had met Russian Oligarch 1 one time. He explained that he worked for Russian Oligarch l’s attorney on litigation matters that involved Russian Oligarch 1 but that he could not provide “specifics” about them for confidentiality reasons. Steele stated that Russian Oligarch 1 had no influence on the substance of his election reporting and no contact with any of his sources. He also stated that he was not aware of any information indicating that Russian Oligarch 1 knew of his investigation relating to the 2016 U.S. elections. 211

210 As we discuss in Chapter Six, members of the Crossfire Hurricane team were unaware of Steele’s connections to Russian Oligarch 1. [redacted]

211 Sensitive source reporting from June 2017 indicated that a [person affiliated] to Russian Oligarch 1 was [possibly aware] of Steele’s election investigation as of early July 2016.

I’m going to save my longer discussion on this for a separate post, though I already flagged and explained why these two footnotes were important in this post. The short version is, it suggests that to the extent the dossier was disinformation, focusing on Carter Page would have given cover for whatever mission Konstantin Kilimnik was pursuing in July 2016, at which point Deripaska may have already known of the dossier (remember he went to Moscow and met with Viktor Yanukovych before the meeting). Note, too, that the redacted word that has been substituted as “possibly aware” is too short to be that uncertain, so I question the substitution. Also note that footnote 210 is one of a handful footnotes in the entire report that was not further declassified with this review.

214: Steele used to be a spook

Steele told us he had a source network in place with a proven “track record” that could deliver on Fusion GPS’s requirements. Steele added that this source network previously had furnished intelligence on Russian interference in European affairs. 214

214 Steele told us that the source network did not involve sources from his time as a former foreign government employee and was developed entirely in the period after he retired from governmental service

This redaction only served to hide what we all knew, that Steele used to be an MI6 officer. Either the UK no longer considers that sensitive or they really want to give Trump what he wants.

242: The Carter Page investigation wasn’t only about whether he was a spy

Case Agent 2 told the OIG that he informed Steele that the FBI was interested in obtaining information in “3 buckets.” According to Case Agent 2’s written summary of the meeting, as well as the Supervisory Intel Analyst’s notes, these 3 buckets were:

(1) Additional intelligence/reporting on specific, named individuals (such as [Page] or [Flynn]) involved in facilitating the Trump campaign-Russian relationship; 241 (2) Physical evidence of specific individuals involved in facilitating the Trump campaign-Russian relationship (such as emails, photos, ledgers, memorandums etc); [and] (3) Any individuals or sub sources who [Steele] could identify who could serve as cooperating witnesses to assist in identifying persons involved in the Trump campaign-Russian relationship. 242

242 The FBI advised the OIG that the Crossfire Hurricane investigation was a national security investigation, and these activities therefor[e] involved national security extraterritorial CHS operations [redaction]

The only thing interesting about this declassification is how it relates the earlier and later ones, at 63 and 526, on special approval for using an informant overseas. It is equally interesting, however, that the description of why FBI focused on what they did remains substantially classified.

244: The FBI’s knowledge of Sergei Millian’s activities remains classified

For example, Steele identified a sub-source (Person 1) who Steele said was in direct contact with Steele’s primary source {Primary Sub-source). 244

244 Person 1 [redacted]

Like the footnote about Crossfire Hurricane’s knowledge of Oleg Deripaska’s ties with Steele, nothing new has been redacted here. Incidentally, after the first batch of these declassifications had come out and I called Sergei Millian out on making a chronologically impossible claim about what they showed, we had a charming exchange where he told me his interest in what I told the FBI was unique, which I include here solely to break up the monotony of this post!

253: Someone told Steele that Millian was hiding out

According to Handling Agent l’s records, during October 2016, Steele communicated with him four times and provided seven written reports, one of which concerned Carter Page and thus was responsive to the FBI’s request for information concerning Page’s activities. 253

253 (U) These seven reports, with selected highlights, were:

(U) Report 130 (Putin and his colleagues were surprised and disappointed that leaks of Clinton’s emails had not had a greater impact on the campaign; a stream of hacked Clinton material had been injected by the Kremlin into compliant western media outlets like WikiLeaks and the stream would continue until the election);

[redacted] Report 132 (a top level Russian intelligence figure claimed that Putin regrets the operation to interfere in the U.S. elections);

(U) Report 134 (a close associate of Rosneft President Sechin confirmed a secret meeting with Carter Page in July; Sechin was keen to have sanctions on the company lifted and offered up to a 19 percent stake in return);

(U) Report 135 (Trump attorney Michael Cohen was heavily engaged in a cover up and damage control in an attempt to prevent the full details of Trump’s relationship with Russia being exposed; Cohen had met secretly with several Russian Presidential Administration Legal Department officials; immediate issues were efforts to contain further scandals involving Manafort’s commercial and political role in Russia/Ukraine and to limit damage from the exposure of Carter Page’s secret meetings with Russian leadership figures in Moscow the previous month);

(U) Report 136 (Kremlin insider reports that Cohen’s secret meeting/s with Kremlin officials in August 2016 was/were held in Prague);

[redacted] Report 137 (Divyekin was moved from his position in the Presidential Administration to one in the Duma; this move followed Divyekin being exposed in the western media, e.g., the Yahoo News story of September 23, 2016, as a secret interlocutor of Page); and

[redacted] Report 139 (Person 1 was forced to lie low abroad following his/her exposure in the western media and was currently in [redacted]).

There are three things about these disclosures. First, the redacted bullets were classified (they had some redaction other than the Unclassified markings these other paragraphs have). If they were known disinformation, it’s not clear why they’d be classified.

Second, this and other declassified passages suggest that FBI had IDed Divyekin (otherwise it’s unlikely to be classified). The application itself said FBI believed this person to be Igor Nikolayevich Dyevkin, who work(ed) in the Presidential Administration. Unless these original redactions were attempts to hide what FBI didn’t know but should have?

The other detail is that — whether disinformation or no — Steele got a report in October, during the month after FBI started actively investigating Millian, that claimed he had hidden out. He was in New York at the time, though, and remained out and about at least through the inauguration (where he partied with Papadopoulos). So why redact his purported locale?

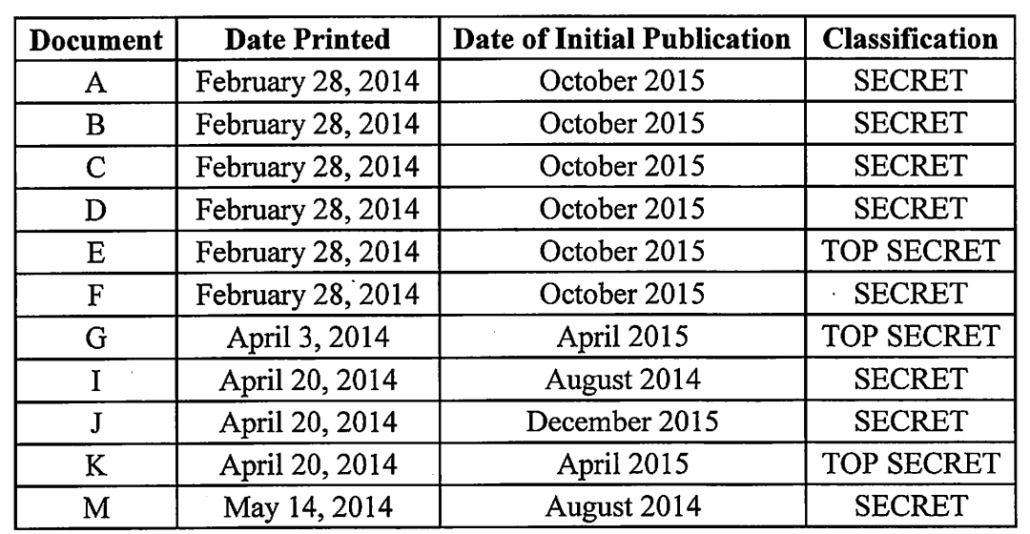

This spreadsheet lists which files the FBI got when.

265: Grenell liberates basic FISA vocabulary that has long been hidden

The same day, OGC submitted a FISA request form to OI providing, among other things, a description of the factual information to establish probable cause to believe that Carter Page was an agent of a foreign power, the “facilities” to be targeted under the proposed FISA coverage, and the FBI’s investigative plan. 265

“Facilities” are the items to be searched or subjected to electronic surveillance, such as email accounts, telephone numbers, physical premises, or personal property.

The term facilities has long been unredacted in reports on FISA, but without a definition (though the definition was obvious). Its declassification is long overdue. That said, this definition leaves out a lot of things that can be defined as facilities, such as IP addresses and encryption keys.

276: The rush to surveil Page before he met with foreigners

3: 11 p.m., Lisa Page to McCabe: “QI now has a robust explanation re any possible bias of the chs in the package. Don’t know what the holdup is now, other than Stu’s continued concerns. Strong operational need to have in place before Monday if at all possible, which means ct tomorrow. 276

As described below, it appears the desire to have FISA authority in place before Monday, October, 17, was due, at least in part, to the fact that Carter Page was expected to travel to the United Kingdom and South Africa shortly thereafter, and the Crossfire Hurricane team wanted FISA coverage targeting Carter Page in place before that trip.

This sounds shocking and any rush may have led to problems with the application (though the most serious problems were more substantive than that). But it’s not unusual to tie surveillance to upcoming foreign activities. After all, FBI is trying to understand what someone’s relationship to foreign governments is. And Page had some pretty interesting meetings in places besides just Russia.

Moreover only the details of where Page was traveling were classified in the original release — a description of his travel appears at 321ff.

293, 362, 368, 377: Individualized FISA orders automatically qualify the target for 705(b) surveillance

Yates signed the application, and OI submitted the application to the FISC the same day. By her signature, and as stated in the application, Yates found that the application satisfied the criteria and requirements of the FISA statute and approved its filing with the court. 293

293 Her signature also specifically authorized overseas surveillance of Carter Page under Section 705(b) of the FISA and Executive Order 12333 Section 2.5

362 Her signature also specifically authorized overseas surveillance of Carter Page under Section 705(b) of the FISA and Executive Order 12333 Section 2.5.

368 Boente’s signature also specifically authorized overseas surveillance of Carter Page under Section 705(b) of the FISA and Executive Order 12333 Section 2.5.

Rosenstein’s signature also specifically authorized overseas surveillance of Carter Page under Section 705(b) of the FISA and Executive Order 12333 Section 2.5.

A set of four footnotes describing that the Attorney General designee signature on the Page applications are one of the declassifications that has been significantly misunderstood.

Under FISA, for authorizations that are more strict (with an individualized content warrant being the most strict), authorization for less or equivalent surveillance is fairly automatic. People targeted with individual orders here in the US must either be covered, when they travel overseas, by 703 (surveillance overseas with the assistance of a US provider) or 704 (surveillance without assistance overseas, meaning EO 12333 surveillance), but there’s an authorization, 705(b), that allows both domestic collection and 12333 collection overseas. As far as all public records and some non-public ones show, 703 has never been used. 705(b) has instead, meaning that when people travel overseas, the government uses techniques available under EO 12333. There’s good reason to believe that the techniques available under 705(b)/EO 12333 are much niftier, including (as one example) more sophisticated device hacks.

I wrote about the import of 705(b) authority with Carter Page back in April 2017 (in a piece that also suggested he might be the first person ever to get to review his FISA application).

That he was approved for 705(b) is important because he was surveilled overseas. But that is in no way unique to Page. Nor, even if this were “physical search” mean they were surveilling his person. A hack of a phone, conducted from Maryland, would qualify.

296: Steele fluffed his MI6 experience

Steele is a former [redacted] and has been an FBI source since in or about October 2013. [Steele’s] reporting has been corroborated and used in criminal proceedings and the FBI assesses [Steele] to be reliable. 296

296 Although Case Agent 2’s summary of the early October meeting with Steele states that Steele described his former position in a manner consistent with the footnote in the FISA application, other documentation (discussed in Chapter Eight) indicates that Steele’s former employer told the FBI in November 2016, after the first application was filed, that Steele had served in a “moderately senior” position, not a “high‐ranking” position as Steele suggested.

This is a complaint about whether Steele or the FBI agent was responsible for the depiction of how he was described in a footnote in the application. It basically shows that Steele fluffed his experience when meeting with the Crossfire Hurricane team, but this kind of distinction is often semantics.

301 to 303: Hiding more details about Sergei Millian

Before the initial FISA application was filed, FBI documents and witness testimony indicate that the Crossfire Hurricane team had assessed, particularly following the information Steele provided in early October, that Source E was most likely a person previously known to the FBI, referred to hereinafter as Person 1. 301

[snip]

In addition, we learned that Person 1 was at the time the subject of an open FBI counterintelligence investigation. 302 We also were concerned that the FISA application did not disclose to the court the FBI’s belief that this sub-source was, at the time of the application, the subject of such an investigation. We were told that the Department will usually share with the FISC the fact that a source is a subject in an open case. The 01 Attorney told us he did not recall knowing this information at the time of the first application, even though NYFO opened the case after consulting with and notifying Case Agent 1 and SSA 1 prior to October 12, 2016, nine days before the FISA application was filed. Case Agent 1 said that he may have mentioned the case to the OI Attorney “in passing,” but he did not specifically recall doing so. 303

301 As discussed in Chapter Four, Person 1 [redacted]

302 According to a document circulated among Crossfire Hurricane team members and supervisors in early October 2016, Person 1 had historical contact with persons and entities suspected of being linked to RIS. The document described reporting [redacted] that Person 1 “was rumored to be a former KGB/SVR officer.” In addition, in late December 2016, Department Attorney Bruce Ohr told SSA 1 that he had met with Glenn Simpson and that Simpson had assessed that Person 1 was a RIS officer who was central in connecting Trump to Russia.

303 Although an email indicates that the OI Attorney learned in March 2017 that the FBI had an open case on Person 1, the subsequent renewal applications did not include this fact. According to the OI Attorney, and as reflected in Renewal Application Nos. 2 and 3, the FBI expressed uncertainty about whether this sub‐source was Person 1. However, other FBI documents in the same time period reflect that the ongoing assumption by the Crossfire Hurricane team was that this sub‐source was Person 1.

301 is one of a small number of footnotes that did not get declassified any further. 302 still hides the source of intelligence claiming that Millian was rumored to be a former Russian intelligence officer, though that Glenn Simpson believed it was not really secret. Clearly there are things about Millian — or about the reporting on Millian — that remain legitimately secret. For some reason, 303 was included on the declassification list even though it had been entirely declassified (it was clearly at least FOUO) for the initial release of the report.

328: Secret discussions sometimes remain secret

Priestap said he interpreted the comments about Steele’s judgment to mean that “if he latched on to something … he thought that was the most important thing on the face of this earth” and added that this personality trait doesn’t necessarily “jump out as a particularly bad or horrible [one]” because, as a manager, it can be helpful if the “people reporting to [you] think the stuff they’re working on is the most important thing going on” and use their best efforts to pursue it. Information from these meetings was shared with the Crossfire Hurricane team. However, we found that it was not memorialized in Steele’s Delta file and therefore not considered in a validation review conducted by the FBI’s Validation Management Unit (VMU) in early 2017. 328

328 Priestap told the OIG that he recalled that he may have made a commitment to Steele’s former employer not to document the former’s employer’s views on Steele as a condition for obtaining the information.

It’s unclear whether DOJ IG doesn’t believe Bill Priestap’s explanation for not including details that might be considered derogatory about Steele. And he’s right that the judgment — that Steele might follow shiny objects — might not be a bad thing in a well-managed source. In any case, the US now appears uninterested in hiding this detail.

334: For some reason Steele’s primary sub-source claimed to believe he was getting paid to meet with friends

As noted in the first FISA application, Steele relied on a primary sub-source (Primary Sub-source) for information, and this Primary Sub-source used a network of sub-sources to gather the information that was relayed to Steele; Steele himself was not the originating source of any of the factual information in his reporting. 334

334 When interviewed by the FBI, the Primary Sub‐source stated that he/she did not view his/her contacts as a network of sources, but rather as friends with whom he/she has conversations about current events and government relations. The Primary Sub‐source [was] [redacted]

This passage (the “was” was previously unredacted but is now redacted) has generated a lot of uncritical attention, as has the DOJ IG Report’s reporting on the primary sub-source generally. One possibility for who this person is is that he’s someone in a British-based Russian community; that community has successfully been targeted for assassination repeatedly (and if the person were in Russia, would be even more vulnerable). If this person was knowingly part of disinformation, undermining Steele would be part of the disinformation. If the person was not, he might want to minimize what he did to avoid assassination himself. But the claim — made here — that someone getting paid to tell Steele these stories (as he was) didn’t realize his network was being treated as subsources is laughable, and reflects more on the reliability of what the Primary Subsource actually said, because it is solid evidence he’s spinning his relationship with Steele.

339: People who would have ties to Russian intelligence are alleged to have ties to Russian intelligence

The Primary Sub-source told the FBI that one of his/her subsources furnished information for that part of Report 134 through a text message, but said that the sub-source never stated that Sechin had offered a brokerage interest to Page. 339

339 The Primary Sub‐source also told the FBI at these interviews that the subsource who provided the information about the Carter Page‐ Sechin meeting had connections to Russian Intelligence Services (RIS). [redacted]

From the day the dossier came out, it was explicit that some of the claimed sources for it had ties to Russian intelligence, and it would be unsurprising if someone close to Igor Sechin did too. The context to this footnote — that the Primary Subsource’s texts with the subsource didn’t reflect any payment to Page — is actually far more damning for Steele (or his Subsource, who for reasons I laid out above, I think shouldn’t be trusted). But the fact that spooks talk to spooks is actually not all that interesting (and in Steele’s dossier, is explicit).

Note there’s a redaction after this claim, which may be an assessment of whether the claim, in this case, makes any sense.

342: On top of disinformation, FBI believed both Steele and his sources may have been boasting

According to the Supervisory Intel Analyst, the cause for the discrepancies between the election reporting and explanations later provided to the FBI by Steele’s Primary Sub-source and sub-sources about the reporting was difficult to discern and could be attributed to a number of factors. These included miscommunications between Steele and the Primary Sub-source, exaggerations or misrepresentations by Steele about the information he obtained, or misrepresentations by the Primary Sub-source and/or sub-sources when questioned by the FBI about the information they conveyed to Steele or the Primary Sub-source. 342

342 In late January 2017, a member of the Crossfire Hurricane team received information [redacted] that RIS [may have targeted Orbis; redacted] and research all publicly available information about it. [redacted] However, an early June 2017 USIC report indicated that two persons affiliated with RIS were aware of Steele’s election investigation in early 2016. The Supervisory Intel Analyst told us he was aware of these reports, but that he had no information as of June 2017 that Steele’s election reporting source network had been penetrated or compromised.

There are two allegations in this newly declassified information. First, that someone on the Crossfire Hurricane team received information that said Steele’s company may have been targeted. And second, a recurring report about one or multiple June 2017 reports stating that Russian intelligence knew of Steele’s efforts in “early” or “July” 2016.

The first claim, with the continued redaction, is unclear about three things: whether Steele was targeted by human or cyber spying, and who conducted the open source investigation, and what the “it” refers to (it could be Orbis, or the attempted targeting of him). It would be thoroughly unsurprising if Steele had been phished, for example, as virtually all anti-Russian entities were in this period. Phishing might have entailed open source investigation into Orbis (but then, so would human targeting). If phishing or any other hacking were successful, Russia might have learned of his project that way.

I’ll deal with this June 2017 report(s) in more depth later. Here, though, the Supervisory Intel Analyst was making a distinction between knowing of Steele’s project and compromising it that may not be entirely credible. It’s important in this context because the FBI did not consider, before Page’s June 2017 FISA application, whether Steele’s allegations about him were disinformation. (Elsewhere, Priestap describes that he considered but dismissed the possibility because he didn’t understand how that would work.)

347: FBI used 702 collection to test Steele’s sub-sources

FBI documents reflect that another of Steele’s sub-sources who reviewed the election reporting told the FBI in August 2017 that whatever information in the Steele reports that was attributable to him/her had been “exaggerated” and that he/she did not recognize anything as originating specifically from him/her. 347

347 The FBI [received information in early June 2017 which revealed that, among other things, there were [redacted]] personal and business ties between the sub-source and Steele’s Primary Sub-source; contacts between the sub-source and an individual in the Russian Presidential Administration in June/July 2016; [redacted] and the sub‐source voicing strong support for candidate Clinton in the 2016 U.S. elections. The Supervisory Intel Analyst told us that the FBI did not have Section 702 coverage on any other Steele sub‐source.

A number of frothy right wingers have pointed to this as further proof of a grand conspiracy. It could be that. But that’s not necessarily what this shows. It does show that 1) the sub-source was in touch with both the primary Subsource (which you’d want to prove to make sure the contact actually happened, and 2) the sub-source had the kind of contacts — with Russia’s Presidential Administration — to reflect actual access to information. The Hillary support absolutely could mean that the sub-source played up whatever he or she had learned from Russian sources, in which his or her claim that Steele’s reporting was exaggerated might be a way to deflect blame. That said, the better part of potential sources for this dossier would not have been pro-Hillary.

The declassification reveals the interesting detail that one and only one of Steele’s subsources was targeted under Section 702.

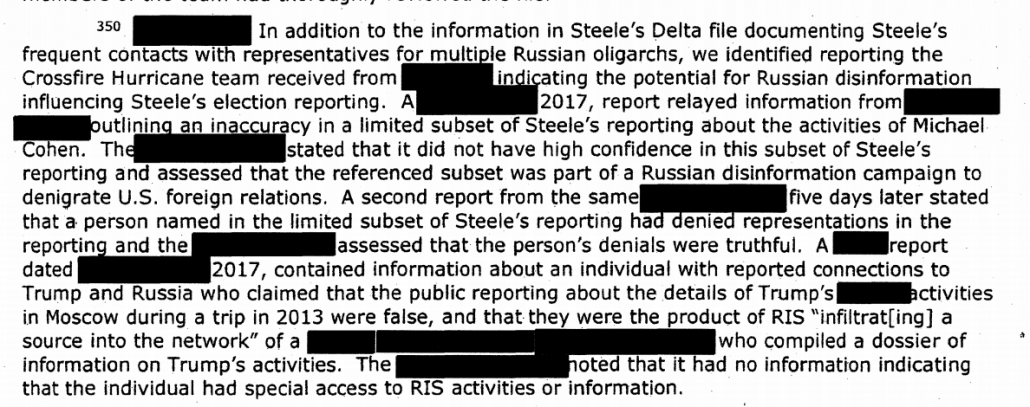

350: The FBI identified the Michael Cohen reporting as erroneous from early on

Stuart Evans, NSD’s Deputy Assistant Attorney General who oversaw OI, stated that if OI had been aware of the information about Steele’s connections to Russian Oligarch 1, it would have been evaluated by OI. He told us: “Counterintelligence investigations are complex, and often involve as I said, you know, double dealing, and people playing all sides…. I think that [the connection between Steele and Russian Oligarch 1] would have been yet another thing we would have wanted to dive into. “350

350 In addition to the information in Steele’s Delta file documenting Steele’s frequent contacts with representatives for multiple Russian oligarchs, we identified reporting the Crossfire Hurricane team received from [redacted] indicating the potential for Russian disinformation influencing Steele’s election reporting. A January 12, 2017, report relayed information from [redacted] outlining an inaccuracy in a limited subset of Steele’s reporting about the activities of Michael Cohen. The [redacted] stated that it did not have high confidence in this subset of Steele’s reporting and assessed that the referenced subset was part of a Russian disinformation campaign to denigrate U.S. foreign relations. A second report from the same [redacted] five days later stated that a person named in the limited subset of Steele’s reporting had denied representations in the reporting and the [redacted] assessed that the person’s denials were truthful. A USIC report dated February 27, 2017, contained information about an individual with reported connections to Trump and Russia who claimed that the public reporting about the details of Trump’s sexual activities in Moscow during a trip in 2013 were false, and that they were the product of RIS “infiltrate[ing] a source into the network” of a [redacted] who compiled a dossier of that individual on Trump’s activities. The [redacted] noted that it had no information indicating that the individual had special access to RIS activities or information.

This footnote is meant to elaborate on Evans’ comment about counterintelligence investigations involving a lot of double dealing, context that is particularly important to reading the still redacted footnote. The footnote explains two things. First, that by January 12, 2017 — that is, days after Buzzfeed published the dossier — what is probably another intelligence service (it could even be the Czechs, given the import of Prague) raised concerns about the accuracy of the subset of reporting on Michael Cohen. Given how Steele represented his reports, however, one set of reports would not necessarily reflect on the accuracy of the others (unless they pointed to disinformation from the primary Subsource); that’s how raw intelligence works! The accuracy of the Cohen reporting does not necessarily reflect on the Page FISA application, which is what this report is about.

The record shows that Mueller did not use the Steele dossier in his investigation of Cohen — which seems to have arisen from Suspicious Activity Reports from his banks showing that immediately after the election a bunch of foreigners, including a key Russian, started paying him large sums. And given what else we know about Cohen, confirmation that this is disinformation actually suggests the disinformation was more sophisticated than otherwise understood, in that it provided cover for other things Russia was doing, something I’ll return to.

As to the 2013 dossier about 2013, because of the redactions, it’s unclear whether the FBI obtained a report of someone reporting that he had learned about a Russian dossier on Trump from his 2013 trip, or that someone else was doing a dossier about someone associated with Trump’s trip. Given what we know from Giorgi Rtskhiladze’s testimony to the FBI and Cohen’s discussion of it since, we already knew there was a dossier material from Trump’s 2013 trip, and had been floated continuously since then. Indeed, this report could actually suggest that the CIA learned of the interactions Rtskhiladze (who had ties to Russia and Trump) had before FBI did.

Update: the version of the footnote that appears in the letter to Grassley shows this footnote was transcribed incorrectly in the full version (replacing “a dossier of information” with “a dossier of that individual”), which raises questions about some of the other transcriptions.

That doesn’t actually change my point:

- At least according to Michael Cohen’s sworn testimony, the alleged pee tape had been out there since 2013

- Giorgi Rtskhiladze is one person — and if Cohen is to be believed, he’s not alone — who knew of the pee tape allegation, and he definitely wanted to claim it was not real (which I’m not contesting), even while having tried to pressure Cohen with it; he also would fit the description of someone who has ties to Russia and Trump but not public ties to Russian intelligence

- The redaction of whose dossier this was — which was DOJ IG’s transcription of the report, not a direct quote — is redacted. If this is about Steele (and I’m not wedded to either reading), then for some reason DOJ IG’s redacted description is sensitive (for some reason they didn’t write “source #1”). And the Steele dossier is not just about Trump’s activities. There are multiple possible explanations for why it is sensitive.

I should not have used “2013” above to distinguish this second claim. But my underlying point remains: in context, that redaction suggests something else is going on.

In any case, I’m grateful to my fan who pointed out the difference in the footnote.

365: Classified stuff about Millian that had already been declassified remains declassified

Renewal Application Nos. 2 and 3 did advise the court of a news article claiming that Person 1 was a source for some of the Steele reports and that Person 1 denied having any compromising information regarding the President. 365

365 In Chapter Five, we describe how the FBI did not specifically and explicitly advise or about the FBI’s assessment before the first FISA application that Person 1 was the sub-source who provided the information relied upon in the application from Steele Reports 80, 95, and 102; that Steele had provided derogatory information regarding Person 1; and that the FBI had an open counterintelligence investigation on Person 1. As noted previously, in the next chapter, we describe the information from the Primary Sub-source interview concerning Person 1 and the information that was not shared with or about inconsistences [sic] between the Primary Sub-source and Steele concerning information provided by Person 1.

As with other instances, there was stuff about Sergei Millian that was declassified for the original release, but as a result was included in this declassification review.

372: FISA collections that corroborated Page’s application has been sequestered

In original form, this footnote (modifying an entirely redacted bullet) described what the third application had said. Because the FISC ordered FBI to sequester all collection from the FISA applications targeting Page, this footnote now marks the information as sequestered.

379: FBI violated minimization procedures in retaining information on Carter Page

According to NSD supervisors, as of October 2019, NSD had not received a formal response from the FISC to the Rule 13 Letter. 379

379 On May 10, 2019, NSD sent a second letter to the FISC concerning the Carter Page FISA applications, advising the court of two indicants in which the FBI failed to comply with the SMPs applicable to physical searches conducted pursuant to the final FISA orders issued by the court on June 29, 2017. According to the letter, the FBI took and retained on an FBI‐issued cell phone photographs of certain property taken in connection with a FISA‐authorized physical search on July 13, 2017, which NSD assessed did not comport with the SMPs. In addition in a separate incident on July 29, 2017, the FBI took photographs in connection with another FISA‐authorized physical search and transferred the photographs to an electronic folder on the FBI’s classified secret network. . According to NSD, court staff contacted an NSD official in response to this letter and asked when the information at issue would be removed from non‐compliant FBI systems, and asked about other cases that might be impacted by the same problem. On October 9, 2019, NSD sent another letter to the FISC advising the court that the FBI completed the remedial process for the information associated with the Page FISA applications and information from other cases impacted by the same problem.

This footnote reveals something specific to Page and more generalized as well. First, FBI did “physical searches” on Page on June 29 and July 13, 2017. Remember, “physical searches” can include searches of stored communication, and in this period, FBI had a specific interest in Page’s use of an encrypted messaging app and bank accounts they had not yet reviewed, so these may not be searches of wherever Page lived at the time (though he has said he was out of the country during one or both of them). It appears the minimization violation pertained to the means by which FBI collected the information, basically by taking a picture of evidence. The language makes it clear that this is a more general problem, one suggesting the FBI had misused cell phones in conjunction with FISA searches (but which are probably totally okay under criminal physical searches).

This is the kind of thing, incidentally, where FBI (or NSA) usually gets FISA to adjust the rules to incorporate such practice, while requiring FBI to purge files of collection that violated the rules when collected.

389: Was the Primary Sub-Source actually not truthful and cooperative?

The Supervisory Intel Analyst did not recall anyone asking him whether he thought the Primary Sub-source was “truthful and cooperative,” as noted in the renewal applications. 389

Email communications reflect that in March 2017—after the first FISA application and first renewal were filed and before the last two renewals—the Supervisory Intel Analyst reviewed the first FISA application and the first renewal at OGC’s request to assist with potential redactions before the Department responded to Congressional information requests. The Supervisory Intel Analyst provided comments to the OGC Attorney, including advising him that the Primary Sub‐source was not [redacted] as stated in the FISA applications, and asking whether a correction should be made. The Supervisory Intel Analyst did not provide any other comments relating to the Primary Sub‐source, and he told us that he did not notice anything else potentially inaccurate or incomplete in the applications at that time.

Nothing new was declassified in this declassification review — the redaction continues to hide what had been claimed about Steele’s Primary Sub-Source. That raises questions about what might still be hidden here, including that there may be some question about how helpful the Primary Sub-Source really was.

475 FBI still had stuff from a pro-Trump informant in their files

The Handling Agent placed the materials into the FBI’s files. 475

475 We notified the FBI upon learning during our review that [redacted] material that the CHS had provided to the FBI were still maintained in FBI files.

This footnote was not further declassified with the declassification review. It pertains to a standing FBI informant who (unbeknownst to the Crossfire Hurricane team) was a part of the Trump campaign and had provided some information to his handler. For some reason, it seems the information should have been removed from FBI files, perhaps because it was disinformation. Note the SSA on this other team was avowedly anti-Hillary and was working on the Clinton Foundation investigation.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)