The Republican PCLOB Cover-Up of NSA’s XKEYSCORE Use Is More Troubling than Tucker Carlson’s Claims To Be Surveilled

The other day, Tucker Carlson claimed that an NSA whistleblower had contacted him to let him know that the NSA was monitoring “our” electronic communications and planned to leak them to take him off the air. Carlson claims the whistleblower’s ability to read back what Carlson said in some texts and emails (both easily hackable communications) about an upcoming story is proof that it happened.

In response, the NSA issued an unprecedented statement via Twitter, reading in part:

This allegation is untrue. Tucker Carlson has never been an intelligence target of the Agency and the NSA has never had any plans to try to take his program off the air.

[snip]

NSA may not target a US citizen without a court order that explicitly authorizes the targeting.

As a number of people have pointed out, given how NSA uses “target” here, this doesn’t amount to a denial, because it’s possible that Carlson’s communications with a foreigner who was legally targeted got swept up. Strictly as a hypothetical, it could be that Carlson is working on another Hunter Biden story involving Ukraine, and the NSA picked up his communications directly with an agent of Russia in Ukraine by targeting that totally legitimate intelligence target. The result would be to incidentally collect Carlson’s communications with said hypothetical Ukrainian target. Particularly if the communications implicating Carlson were damning and potentially illegal, leaking them to him would be an easy way to flip the story, and accuse NSA of spying rather than Carlson of coordinating with Russian agents. Again, that’s all just a hypothetical that might explain Carlson’s claims.

Still, given that Carlson is a liar who has recently been spewing conspiracy theories that are whack even for him, my default assumption is that he’s lying.

Meanwhile, Carlson’s little cultivated outrage occurs at the same time that Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board member Travis LeBlanc released a scathing dissent, dated March 12, 2021 but just declassified, from a recently released but still classified PCLOB report on the NSA’s use of XKEYSCORE. The statement points to problems with both the use of XKEYSCORE and EO 12333 generally, as well as the operation of PCLOB under the recently departed Adam Klein’s tenure as Chair. Together, LeBlanc’s complaint suggests that Klein may have deliberately protected NSA from scrutiny after violations that happened during the Trump Administration were discovered in November 2020.

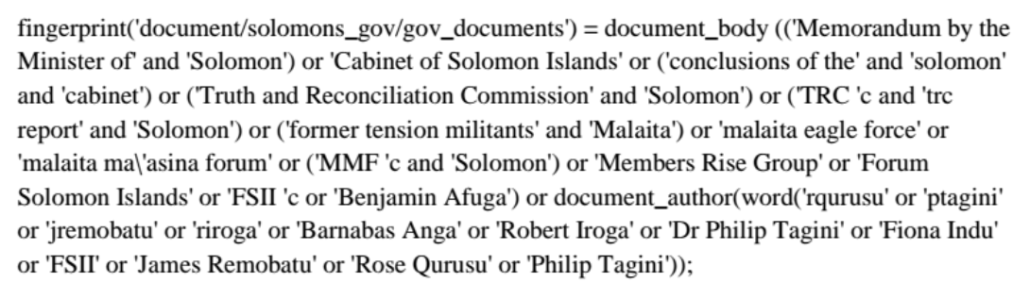

XKEYSCORE is effectively a means of querying the Five Eyes collections for all information on a target. Here’s what a query, called a “fingerprint,” targeting a peace and reconciliation commission in the Solomon Islands, looks like:

PCLOB started investigating XKEYSCORE in 2014 as part of its review of a limited subset of programs authorized under EO 12333.

The NSA deep dive concerned NSA’s use of XKEYSCORE, an intelligence analysis tool. The Board received briefings from and held meetings with NSA staff between May 2015 and November 2016. The Board also reviewed the guidance and training provided to NSA personnel, compliance mechanisms, and the relationship between the NSA activity and the NSA’s EO 12333 implementing procedures.

In early 2019, after the Board regained a quorum, the Board reengaged with the NSA and received additional briefings, demonstrations, and information. During this process, the Board worked with NSA to confirm and update facts provided in the 2015 timeframe. Again, the Board concentrated on the protection of U.S. persons’ privacy and civil liberties.

The Board produced a detailed, classified report explaining NSA’s use of XKEYSCORE as an analytic tool and relevant privacy and civil liberties protections in late 2020. Accompanying the report were recommendations from the Board and additional views of individual Board Members. The report and recommendations were delivered to the NSA, Congress, and other relevant executive branch agencies.

But PCLOB, under Klein’s leadership, chose not to declassify any parts of the report on XKEYSCORE.

In his dissent, LeBlanc laid out a bunch of problems with the Report itself:

- PCLOB didn’t address any of the technological questions presented by the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning

- PCLOB didn’t unpack the jargon NSA uses by separating discovery, targeting, and acquisition activities that can — and LeBlanc strongly implies does — result in domestic collection

- PCLOB did not conduct the kind of efficacy review that its three earlier surveillance reports had done (which showed, for example, that the phone dragnet had never been really useful)

- PCLOB didn’t adequately chase down the legal justification for XKEYSCORE and closed up shop before examining 2019 violations disclosed in November 2020

- PCLOB refused to adopt recommendations made by LeBlanc and Ed Felton, including one (to tag communications believed to belong to a US person) that would not be burdensome but would ensure that such US person communications would be not picked up in the future

- PCLOB didn’t release the report

- The former GOP majority rushed to finalize this report before Republicans lost the majority on it

Of particular note, LeBlanc suggests that (as happened with the phone dragnet), NSA had not conducted any legal analysis specific to XKEYSCORE before PCLOB asked for it in 2015.

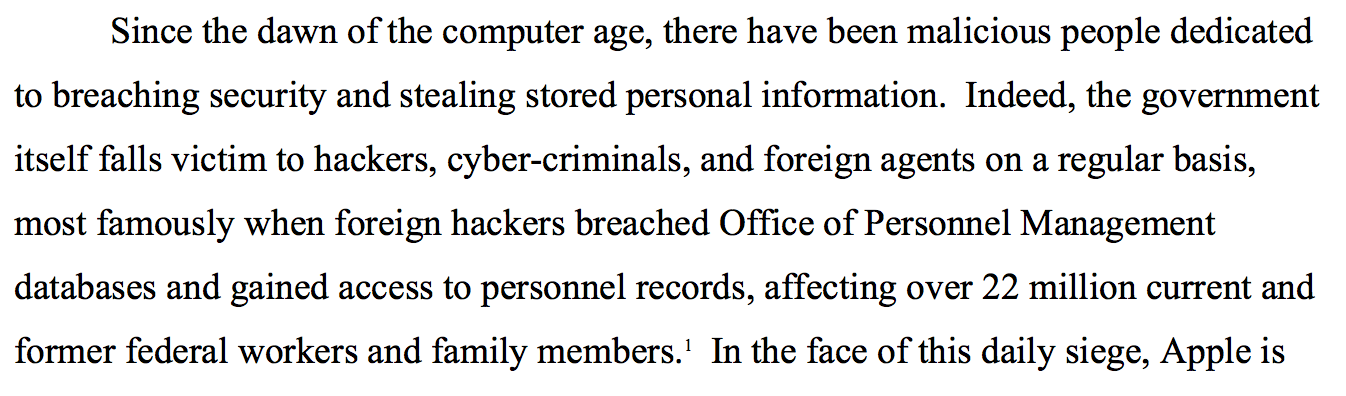

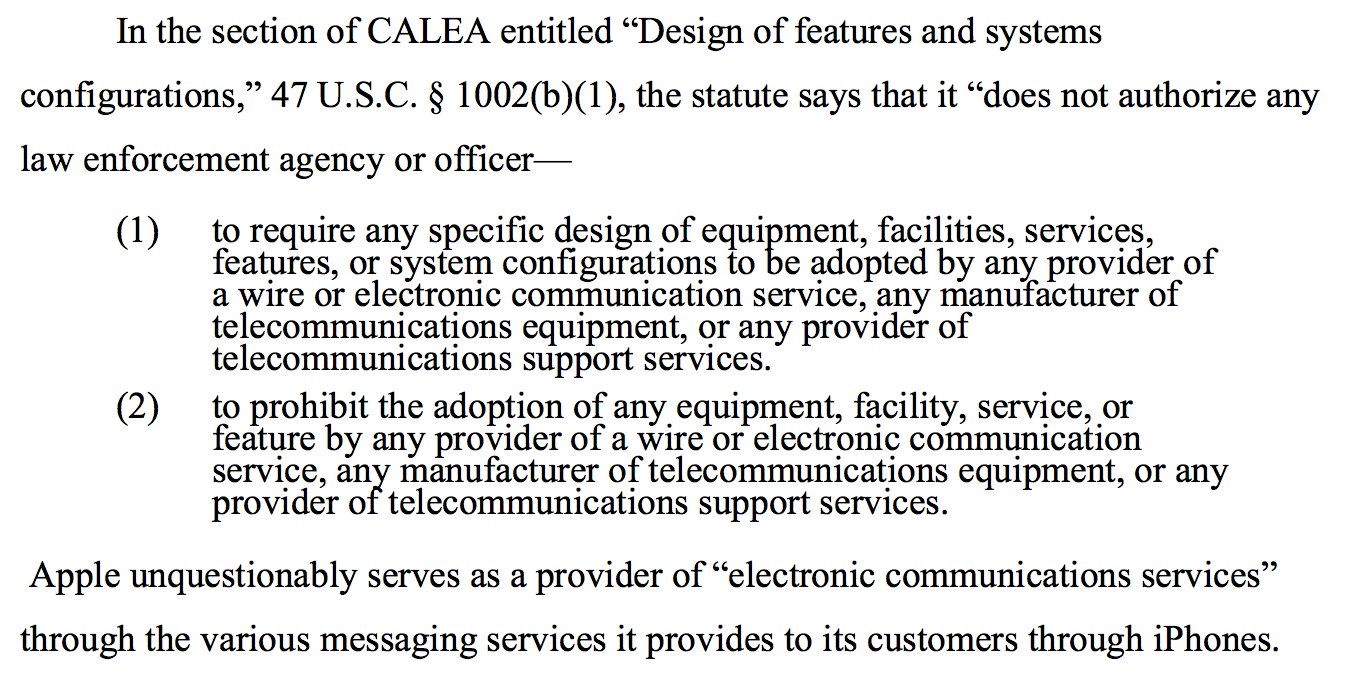

Surprisingly, when the Board requested any legal analysis by the NSA or the Department of Justice regarding the use of XKEYSCORE’s functions in 2015, the NSA responded with a 13-page memo prepared by the NSA Office of General Counsel in 2016. Setting aside such a legal analysis was first written in January 2016, it is equally concerning that the agency apparently has not updated that written legal analysis since then. At a general level and on the basis of the documents that have been provided to the Board, it is concerning that any surveillance tool woul have been conceptualized, coded, implemented, and then executed and routinely used without such a prior legal analysis. Further, the analysis that NSA provided in 2016 fundamentally rests on decades-old Supreme Court precedent from United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, Smith v. Maryland, Katz v. United States, and two DOJ legal memoranda from the 1980s to assert that collection and use of XKEYSCORE is consistent with the Fourth Amendment.35 The NSA’s legal analysis lacks any consideration of recent relevant Fourth Amendment case law on electronic surveillance that one would expect to be considered–for example, Carpenter v. United States, Riley v. California, United States v. Jones, and United States v. Maynard. [some footnotes omitted]

Half of that footnote 35 — probably the bits that refer to DOJ memos likely including a 1984 OLC memo written by Ted Olson that DOJ is still hiding — is redacted.

The likelihood that none of this complies with the Fourth Amendment is all the more troubling given the disclosure of recent violations using XKEYSCORE and the way, subsequent to those violations, the GOP Majority rushed to finish the report before losing a majority on PCLOB.

In one of the most heavily redacted paragraphs in LeBlanc’s declassified dissent, he explains how PCLOB didn’t investigate reports of 2019 violations uncovered in November 2020.

I am equally concerned that the Board’s former majority failed to investigation [redacted] of serious compliance reports involving XKEYSCORE prior to approving this report. During the former Board’s investigation, it was uncovered in November 2020 that some [redacted] compliance reports involving XKEYSCORE occurred in 2019. Of those [redacted] XKEYSCORE reporters, [redacted] were deemed upon agency review to involve Questionable Intelligence Activities (“QIAs”). QIAs are defined as “any intelligence or intelligence-related activity when there is reason to believe such activity is unlawful or contrary to an EO, Presidential Directive, [Intelligence Community] Directive, or applicable DOD policy governing the activity. [entire sentence redacted] Obviously, violations of U.S. law and the known collection of processing of U.S. person information are serious compliance issues. Yet the former Board did not request specific information [full line redacted]

Ellen Nakashima’s story on this dissent reveals there were hundreds of such reports.

The program also resulted in hundreds of compliance incidents in 2019, a majority of which were considered “questionable intelligence activities” — a category that means the action may have involved improper surveillance of Americans’ communications, according to U.S. officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because details are classified.

As LeBlanc describes it (though much of that is redacted), when PCLOB heard about these hundreds of violations that happened under Donald Trump in the same month that Trump lost the presidency, they didn’t ask what happened.

Instead, they rushed to complete the still unfinished report while they retained a majority.

I have several concerns about the Board process that was followed to apparently approve the unfinished report. In a December 2020 Board meeting, the former majority sought ot vote on the then-unfinished XKEYSCORE report. During the Board meeting at which the vote was taken, we spent several hours discussing the revisions to the body and recommendations that would need to be made to the report. Instead of completing those revisions and then providing sufficient time for Members to review the report and prepare their statements before voting, the former Board majority sought in that meeting to approve the report for this project, ostensibly foreseeing the expiration of former Member Aditya Bamzai’s term at the end of December. Literally on the evening of December 21, former Member Bamzai circulated his statement. Subsequently, the new Board convened in January 2021 and then-Chairman submitted his own intention to resign the same month. Recognizing that the current 2021 Board has not voted on a report that we were still considering for revision as I drafted this statement, I have repeatedly requested a vote by the current Board on the final version of this report, including all final statements of current Members as well as a vote on whether to include the statement of a former Member. The then-current Chairman created a legal fiction to compel the issuing of a former Member’s statement without so much as a vote of the current Board to release this report. I simply cannot support a report that has not been voted on by the current Board that will issue it.

Even while he was pulling a fast one to close up the review of XKEYSCORE before it was done, Klein was writing his own White Paper on FISA that made claims about the soundness of FISA that he had no ability to conclude (most importantly, because PCLOB did not receive any of the applications implicating Sensitive Investigative Matters that should get the most scrutiny.

There were two claims of improper surveillance by NSA in recent days. One, made by a serial fabulist. And another, made by someone with access to classified information, that may affect hundreds of Americans.

The refusal of Republicans on PCLOB to examine the latter violations merits far more attention given the credibility of the reporting source than Tucker Carlson’s claims.