Bill Barr Claimed a Threat Meriting a Four Subpoena Investigation Didn’t Merit a Sentencing Enhancement

In the aftermath of the Proud Boys-led insurrection, I’ve been reporting over and over on how Bill Barr’s DOJ treated threats by the Proud Boys against Amy Berman Jackson — which the probation office treated as the same kind of threat as the obstruction charge being used against many of the January 6 defendants — as a technicality unworthy of a sentencing enhancement.

Katelyn Polantz advanced that story last night, reporting that DOJ subpoenaed the four Proud Boys implicated by Roger Stone in his threat against ABJ for grand jury testimony.

Stone — testifying at a court hearing in 2019 to explain the post — said at the time that a person working with him on his social media accounts had chosen it.

Then, at another hearing the same year, Stone named names. Tarrio, the leader of the Proud Boys, had been helping him with his social media, Stone said under oath, as had the Proud Boys’ Florida chapter founder Tyler Ziolkowski, who went by Tyler Whyte at the time; Jacob Engels, a Proud Boys associate who is close to Stone and identifies himself as a journalist in Florida; and another Florida man named Rey Perez, whose name is spelled Raymond Peres in the court transcript.

A few days later, federal authorities tracked down the men and gave them subpoenas to testify to a grand jury, according to Ziolkowski, who was one of the witnesses.

Ziolkowski and the others flew to DC in the weeks afterwards to testify.

“They asked me about if I had anything to do about posting that. They were asking me if Stone has ever paid me, what he’s ever paid me for,” Ziolkowski told CNN this week. When he first received the subpoena, the authorities wouldn’t tell Ziolkowski what was being investigated, but a prosecutor later told him “they were investigating the picture and if he had paid anybody,” Ziolkowski said. He says he told the grand jury Stone never paid him, and that he hadn’t posted the photo.

Tarrio and Engels did not respond to inquiries from CNN, and Stone declined to respond to CNN’s questions. The FBI’s Washington, DC, office did not respond to requests for comment from CNN.

A person familiar with the case said it had closed without resulting in any charges.

For what it’s worth, given the interest Mueller showed in Stone’s social media work, given the close ties between Stone’s social media work and that of the Proud Boys, and given that parts of the investigation against Stone continued well after his trial, it’s possible prosecutors used Stone’s comments as a way to ask other questions: about whether Stone had paid four of his closest buddies in the Proud Boys (remember they were also looking for a notebook Stone used for his 2016 book that recorded all of his communications with Trump).

That said, DC’s US Attorney’s office paid for four witnesses to come to DC to testify about whether they had had a role in Stone’s threats against the judge presiding over his case.

That raises the stakes on the things Barr said publicly about this threat. As noted, in a sentencing memo written as Barr’s urging, DOJ claimed that the threat against ABJ “overlap[ped] … with the offense conduct in this case.”

Second, the two-level enhancement for obstruction of justice (§ 3C1.1) overlaps to a degree with the offense conduct in this case. Moreover, it is unclear to what extent the defendant’s obstructive conduct actually prejudiced the government at trial.

And DOJ dismissed the import of a threat against a judge by suggesting that if it didn’t prejudice prosecutors at trial, it doesn’t much matter.

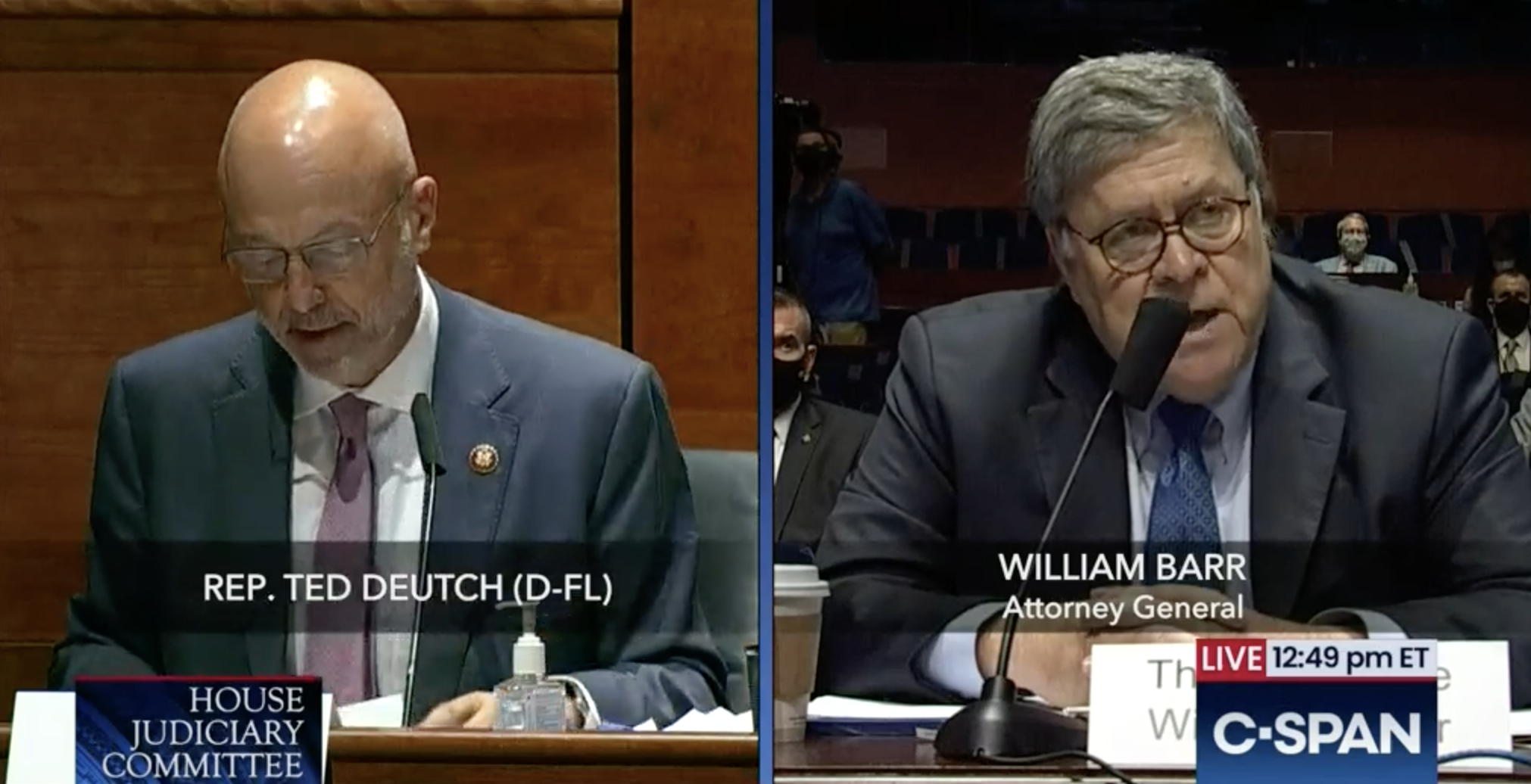

More problematic still was Barr’s testimony before House Judiciary Committee last July, just over two months before the President said the Proud Boys should “stand back and stand by.”

When Congressman Ted Deutch asked Barr if he could think of any other case where threatening to kill a witness and then threatening a judge were treated as mere technicalities, Barr kept repeating, at least five times, that “the Judge agreed with me.”

Deutch: You said enhancements were technically applicable. Mr. Attorney General, can you think of any other cases where the defendant threatened to kill a witness, threatened a judge, lied to a judge, where the Department of Justice claimed that those were mere technicalities? Can you think of even one?

Barr: The judge agreed with our analysis.

Deutch: Can you think of even one? I’m not asking about the judge. I’m asking about what you did to reduce the sentence of Roger Stone?

Barr: [attempts to make an excuse]

Deutch: Mr. Attorney General, he threatened the life of a witness —

Barr: And the witness said he didn’t feel threatened.

Deutch: And you view that as a technicality, Mr. Attorney General. Is there another time

Barr: The witness — can I answer the question? Just a few seconds to answer the question?

Deutch: Sure. I’m asking if there’s another time in all the time in the Justice Department.

Barr: In this case, the judge agreed with our — the judge agreed with our —

Deutch: It’s unfortunate that the appearance is that, as you said earlier, this is exactly what you want. The essence of rule of law is that we have one rule for everybody and we don’t in this case because he’s a friend of the President’s. I yield.

That claim — that ABJ agreed with the analysis of Barr and his flunkies — was a lie, a lie made under oath. ABJ, a liberal judge without Barr’s lifetime authoritarian claims about crime, believed the sentencing guidelines are too harsh. She did not believe these enhancements were mere technicalities.

Indeed, in ruling that the enhancement for the threat against her applied — a threat against official proceedings, the same charge being used against many of the insurrectionists — she talked about how posting a threat on social media, “increased the risk that someone else, with even poorer judgment than he has, would act on his behalf.”

I suppose I could say: Oh, I don’t know that I believe that Roger Stone was actually going to hurt me, or that he intended to hurt me. It’s just classic bad judgment.

But, the D.C. Circuit has made it clear that such conduct satisfied the test. They said: To the extent our precedent holds that a §3C1.1 enhancement is only appropriate where the defendant acts with the intent to obstruct justice, a requirement that flows logically from the definition of the word “willful” requires that the defendant consciously act with the purpose of obstructing justice.

However, where the defendant willfully engages in behavior that is inherently obstructive, that is, behavior that a rational person would expect to obstruct justice, this Court has not required a separate finding of the specific intent to obstruct justice.

Here, the defendant willfully engaged in behavior that a rational person would find to be inherently obstructive. It’s important to note that he didn’t just fire off a few intemperate emails. He used the tools of social media to achieve the broadest dissemination possible. It wasn’t accidental. He had a staff that helped him do it.

As the defendant emphasized in emails introduced into evidence in this case, using the new social media is his “sweet spot.” It’s his area of expertise. And even the letters submitted on his behalf by his friends emphasized that incendiary activity is precisely what he is specifically known for. He knew exactly what he was doing. And by choosing Instagram and Twitter as his platforms, he understood that he was multiplying the number of people who would hear his message.

By deliberately stoking public opinion against prosecution and the Court in this matter, he willfully increased the risk that someone else, with even poorer judgment than he has, would act on his behalf. This is intolerable to the administration of justice, and the Court cannot sit idly by, shrug its shoulder and say: Oh, that’s just Roger being Roger, or it wouldn’t have grounds to act the next time someone tries it.

The behavior was designed to disrupt and divert the proceedings, and the impact was compounded by the defendant’s disingenuousness.

This warning about what happens when people post inciteful language on Instagram might well have served as a warning in advance of January 6. But Barr, in testimony under oath to House Judiciary Committee, pretended that his DOJ had not ignored such a threat.

While it didn’t make the sentencing guidelines, the Proud Boy-linked threats to Credico were sufficiently serious that under FBI’s Duty to Warn, they alerted Credico to the threats. Now we learned that line prosecutors treated the threat against ABJ as sufficiently serious that they obtained grand jury subpoenas to learn more about it.

And in testimony under oath, Bill Barr pretended that ABJ agreed — and it was reasonable for his office to treat — such threats as mere technicalities.