Symbolic Violence In Politics

Posts on Pierre Bourdieu: link

Posts on The Dawn Of Everything: Link

Posts trying to cope with the absurd state of political discourse: link

I’m well into The Dawn Of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow. They bring the perspectives of anthropology and archaeology.

I think the insights of contemporary sociology will help us understand a bit better some of the ideas the authors explore. It seems reasonable to me that if we are going to treat our ancestors as pretty much just like us then what we have learned about the ways we structure our society might be helpful in understanding some of the ways they structured theirs. To that end, let’s revisit the sociology of Pierre Bourdieu.

Like a lot of the French thinkers I’ve read, Bourdieu creates his own vocabulary. Two important termss are “habitus” and “field”. Another is “capital”, which includes several different named forms, the most important of which are economic capital and cultural capital. I discuss these terms in this series, and discuss others in a vocabulary post.

I discussed another of his terms, symbolic violence, in this post, focusing on how it worked to instill neoliberal ideas into the field of economics and on to the general public. This post holds up well, and is a good introduction to the concept in a fairly neutral context.

Keith Topper’s paper Not So Trifling Nuances: Pierre Bourdieu, Symbolic Violence, and the Perversions of Democracy, 8 Constellations 30, 2001, is available here. Topper is a political scientist at U. Cal. Irvine. The paper discusses the applicability of Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence in a political science. In Section I he introduces the basic ideas of practice, habitus and field.

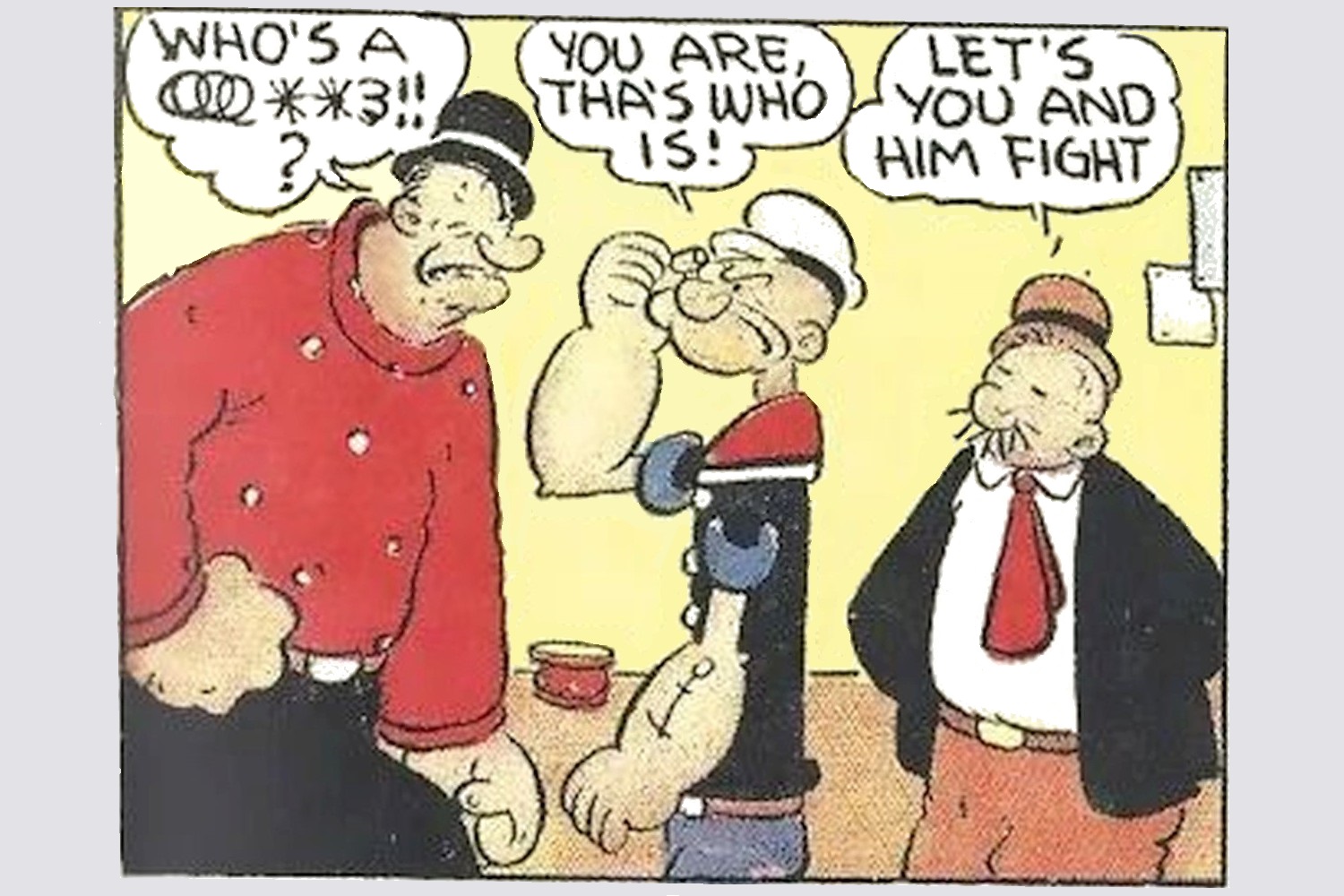

In Section II he discusses Bourdieu’s interest in what he calls ordinary violence, those everyday interactions among people that are marked by “violence, domination, denigration, and exclusion in everyday affairs”. These mostly go unnoticed because they are routine, but they are the primary way that dominance is maintained. These interactions are spoken, and for Bourdieu language is a tool for domination.

Here are two examples I think demonstrate this point. The first is from a Lenny Bruce stand-up routine, taken from The Essential Lenny Bruce by Jack Cohen (my transcription).

I wonder if we’ll ever see that — if we’ll ever see the Southerner get any acceptance at all. … That’s why Lyndon Johnson is a fluke — because we’ve never had a president with a sound like that. Cause we know in our culture that “people who tawk lahk thayat” — they may be bright, articulate, wonderful people — but “people who tawk lahk thayat are shitkickuhs.” As bright as any Southerner could be, if Albert Einstein “tawked lahk thayat, theah wouldn’t be no bomb::

“Folks, ah wanna tell ya bout new-cleer fishin—”

“Get outta here, schmuck!’

“How come ah’m a schmuck?”

“Cause you ‘tawk lahk thayat,’ that’s why.”

“But ah’m tawking some stuff, buddi.”

“Will you stop, you nitwit, and get outta here? You’re wasting our time.” P. 97-8.

My second example is from this 2005 article in the New York Times. It describes the concerns of Della Mae Justice, an Appalachian woman from a poor family who, with the help of a wealthy cousin, is now a successful lawyer.

Far more than people who remain in the social class they are born to, surrounded by others of the same background, Ms. Justice is sensitive to the cultural significance of the cars people drive, the food they serve at parties, where they go on vacation — all the little clues that indicate social status. By every conventional measure, Ms. Justice is now solidly middle class, but she is still trying to learn how to feel middle class. Almost every time she expresses an idea, or explains herself, she checks whether she is being understood, asking, “Does that make sense?”

…And though in terms of her work Ms. Justice is now one of Pikeville’s (Kentucky) leading citizens, she is still troubled by the old doubts and insecurities. “My stomach’s always in knots getting ready to go to a party, wondering if I’m wearing the right thing, if I’ll know what to do,” she said. “I’m always thinking: How does everybody else know that? How do they know how to act? Why do they all seem so at ease?”

Bourdieu is especially concerned with the way one’s speaking style can create dominant and subservient attitudes. I’ll summarize this point as I currently understand it. Each of us has a habitus, a set of dispositions that guide our social interactions. As a trivial example, most people use politeness terms, please and thank you, without thinking. Habitus also guides the way we dress, hold ourselves, those matters Ms Justice is worried about, and pretty much all our actions.

Bourdieu thinks we have a linguistic habitus. The linguistic habitus includes both words and manner of speech, but also gestures, interruptions and the expectations we have about how our speech will be received. Bourdieu also thinks participants in different fields, like law, academia, and corporate life, each require a different linguistic habitus.

Those who lack the kinds of linguistic habitus preferred in a particular field are excluded from participation in the field. The paper I’m describing is a perfect example of the linguistic habitus required in the field of political science. I’m on my third reading and it’s unbearably dense. But it wasn’t written for me. It was written at to communicate with other participants in Topper’s field. I’d be excluded from participating in a written discussion of this paper because I do not know the literature and I don’t understand the problem he intended to address. Also, I don’t like to write like that.

Topper seems to think there is a preferred linguistic habitus in politics, and those who don’t have it are excluded from participating in political discussion. It’s not just that those who have the preferred linguistic habitus ignore or dismiss them, though that can happen. They exclude themselves. They are self-silenced by their own recognition of a perceived deficiency.

Topper says this seriously undercuts the legitimacy of decisions made in the absence of the voices of too many people. He says neither the people with political linguistic competence, nor the people excluded recognize that the exclusion is based on a form of intimidation, silent but effective. This is the sense in which the control of symbolic discourse can be understood as violent.

Topper points out that language is a crucial part of politics. He cites Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition.

In this work Arendt holds that the very essence of politics is speech – specifically, public speech made possible by a shared language. Divested of the capacity to speak, and accordingly to listen, to persuade and to be persuaded, politics would be inconceivable, supplanted instead by “sheer violence,” which, she adds forebodingly, is necessarily “mute.

There is a similar discussion in The Origins Of Totalitarianism. Arendt says that the Nazis first denationalized the Jews, taking away their ability to speak and to act as citizens. That step made them less than human in Arendt’s terms, not much different from animals. P. 447.

Topper draws two conclusions. First, restricting participation to those with certain linguistic habitus means that other people are excluded from the political sphere. It undercuts our claim to self-government if large numbers of us can’t or won’t participate.

Second, the unequal distribution of acceptable political linguistic habitus is not formally recognized and counteracted, by education or otherwise. Thus, the dominant class can deny that it is exclusionary, and the subservient class can’t see exactly how it is being treated unfairly. This has major implications for political theory, which I’ll skip. It also has real world implications, which Topper doesn’t discuss in this paper.

Discussion.

1. There’s a lot here to consider. I think this idea, symbolic violence, is a helpful lens for a lot of different things including my reading of The Dawn Of Everything. There are too many for this post.

2. One specific thing is the whinging of David Brooks about the hurt feelings of those he claims are excluded by the culturally dominant, and how that led to the election of Trump. It’s obviously not true that right-wingers are excluded from public discourse, or from cultural discourse. I’ll take that up in another post.

======

Picture by Jim Surkamp via Flickr