WAG: The Government Made a Significant FISA Back Door Request Just Before December 9, 2015

As I’ve noted, we can be virtually certain that the government has started demanding back doors from tech companies via FISA requests, including Section 702 requests that don’t include any court oversight of assistance provided. Wyden said as much in his statement for the SSCI 702 reauthorization bill request.

It leaves in place current statutory authority to compel companies to provide assistance, potentially opening the door to government mandated de-encryption without FISA Court oversight.

We can point to a doubling of Apple national security requests in the second half of 2016 as one possible manifestation of such requests.

The number of national security orders issued to Apple by US law enforcement doubled to about 6,000 in the second half of 2016, compared with the first half of the year, Apple disclosed in its biannual transparency report. Those requests included orders received under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, as well as national security letters, the latter of which are issued by the FBI and don’t require a judge’s sign-off.

We might even be able to point to a 2015 request that involved an amicus (likely Amy Jeffress) and got appealed.

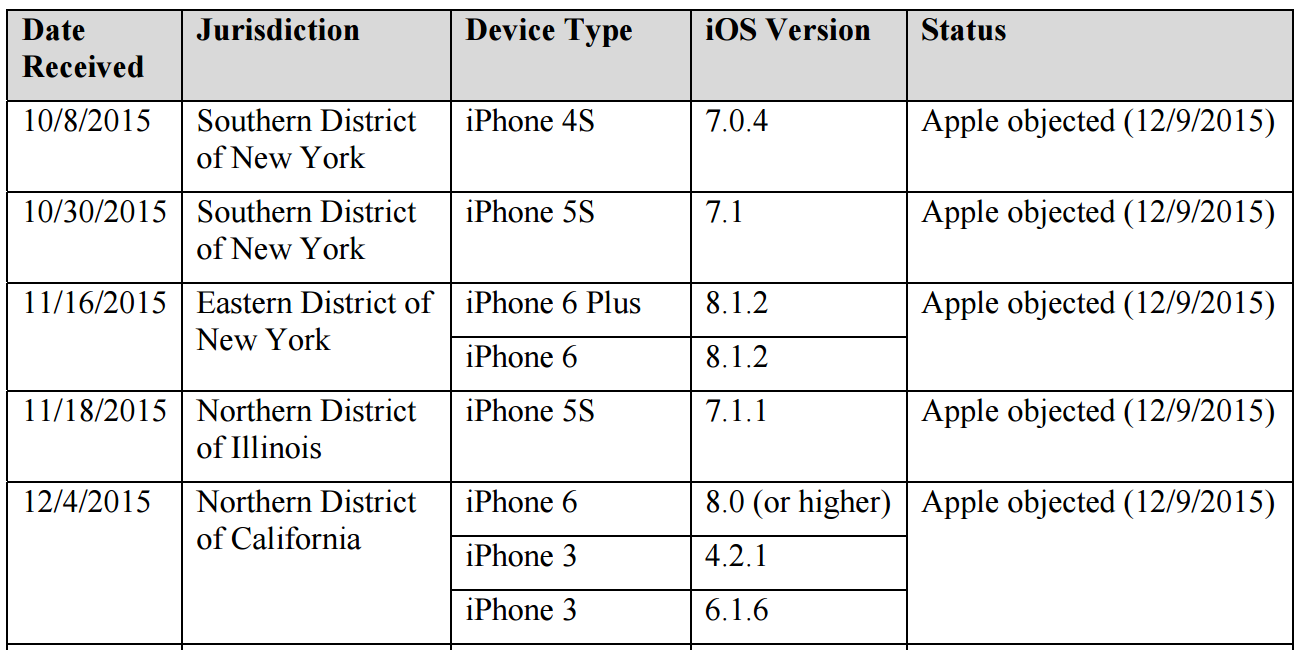

Given those breadcrumbs, I want to return to this post on the demand for a back door into the work phone of the San Bernardino killer, Syed Rezwan Farook. In it, I presented a number of other data points to suggest such a request may have come in late 2015. First, in a court filing, Apple claimed to object to a bunch of requests for All Writs Act assistance to break into its phones on the same day, December 9, 2015.

As I noted the other day, a document unsealed last week revealed that DOJ has been asking for similar such orders in other jurisdictions: two in Cincinnati, four in Chicago, two in Manhattan, one in Northern California (covering three phones), another one in Brooklyn (covering two phones), one in San Diego, and one in Boston.

According to Apple, it objected to at least five of these orders (covering eight phones) all on the same day: December 9 (note, FBI applied for two AWAs on October 8, the day in which Comey suggested the Administration didn’t need legislation, the other one being the Brooklyn docket in which this list was produced).

The government disputes this timeline.

In its letter, Apple stated that it had “objected” to some of the orders. That is misleading. Apple did not file objections to any of the orders, seek an opportunity to be heard from the court, or otherwise seek judicial relief. The orders therefore remain in force and are not currently subject to litigation.

Whatever objection Apple made was — according to the government, anyway — made outside of the legal process.

But Apple maintains that it objected to everything already in the system on one day, December 9.

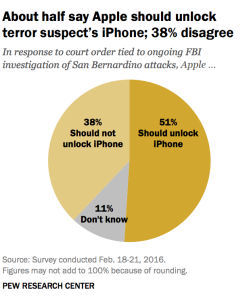

Why December 9? Why object — in whatever form they did object — all on the same day, effectively closing off cooperation under AWAs in all circumstances?

I suggested that one explanation might have been a FISA request for the same thing. Apple would know that FISC takes notice of magistrate decisions, and would want to avoid fighting that battle on two fronts.

There are two possibilities I can think of, though they are both just guesses. The first is that Apple got an order, probably in an unrelated case or circumstance, in a surveillance context that raised the stakes of any cooperation on individual phones in a criminal context. I’ll review this at more length in a later post, but for now, recall that on a number of occasions, the FISA Court has taken notice of something magistrates or other Title III courts have done. For location data, FISC has adopted the standard of the highest common denominator, meaning it has adopted the warrant standard for location even though not all states or federal districts have done so. So the decisions that James Orenstein in Brooklyn and Sheri Pym in Riverside make may limit what FISC can do. It’s possible that Apple got a FISA request that raised the stakes on the magistrate requests we know about. By objecting across the board — and thereby objecting to requests pertaining to iOS 8 phones — Apple raised the odds that a magistrate ruling might help them out at FISA. And if there’s one lawyer in the country who probably knows that, it’s Apple lawyer Marc Zwillinger.

At the time, Tim Cook suggested that “other parts of government,” aside from the FBI, were asking for more, suggesting the NSA might be doing so.

Aside the obvious reasons to wonder whether Apple got some kind of FISA request, in his interview with ABC the other day, Tim Cook described “other parts of government” asking for more and more cases (though that might refer to state and city governments asking, rather than FBI in a FISA context).

The software key — and of course, with other parts of the government asking for more and more cases and more and more cases, that software would stay living. And it would be turning the crank.

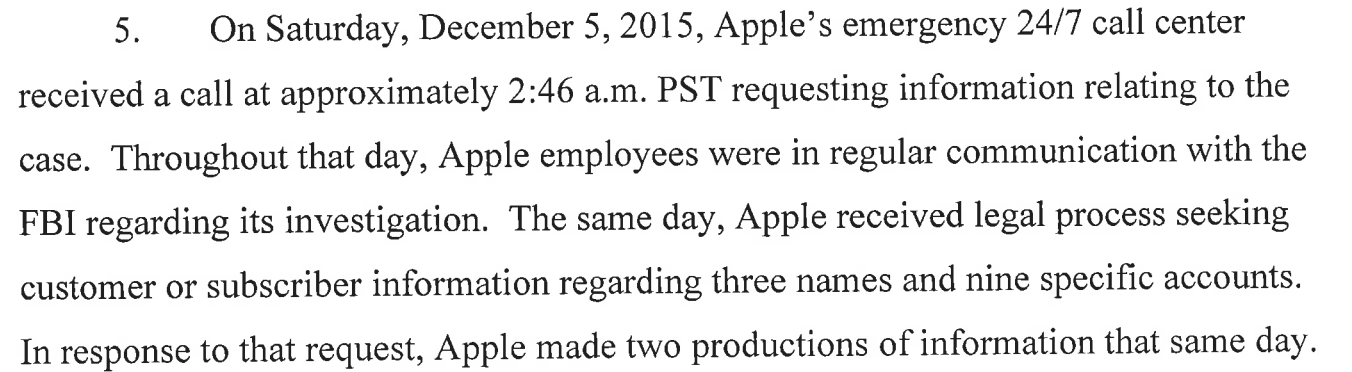

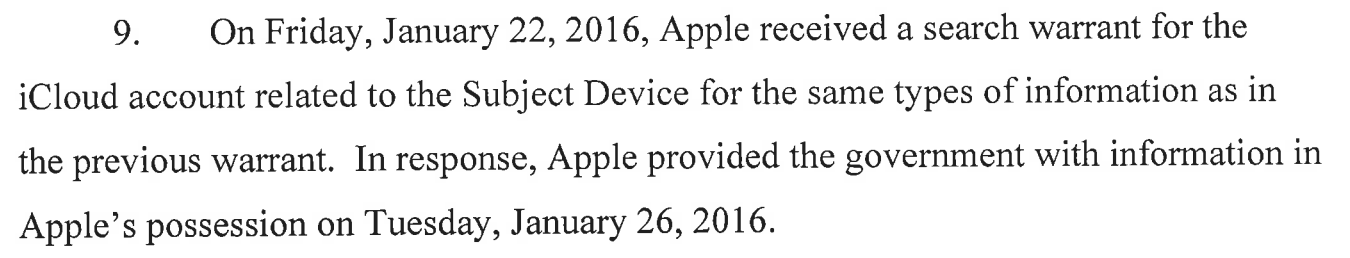

The other possibility is that by December 9, Apple had figured out that — a full day after Apple had started to help FBI access information related to the San Bernardino investigation, on December 6 — FBI took a step (changing Farook’s iCloud password) that would make it a lot harder to access the content on the phone without Apple’s help.

Obviously, there are other possible explanations for these intersecting breadcrumbs (including that the unidentified 2015 amicus appointment was for some other issue, and that it didn’t relate to appeals up to and including the Supreme Court). But if these issues were all related it’d make sense.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)