Insurance File: Glenn Greenwald’s Anger Is of More Use to Vladimir Putin than Edward Snowden’s Freedom

Glenn Greenwald risks making his own anger more valuable to Vladimir Putin than Edward Snowden’s freedom.

When WikiLeaks helped Snowden flee Hong Kong eight years ago, both WikiLeaks and Snowden had the explicit goal of using Snowden’s successful flight from prosecution to entice more leakers.

In his book, Snowden described that Sarah Harrison and Julian Assange’s goal in helping him flee Hong Kong was to provide a counterexample to the draconian sentence of Chelsea Manning.

People have long ascribed selfish motives to Assange’s desire to give me aid, but I believe he was genuinely invested in one thing above all—helping me evade capture. That doing so involved tweaking the US government was just a bonus for him, an ancillary benefit, not the goal. It’s true that Assange can be self-interested and vain, moody, and even bullying—after a sharp disagreement just a month after our first, text-based conversation, I never communicated with him again—but he also sincerely conceives of himself as a fighter in a historic battle for the public’s right to know, a battle he will do anything to win. It’s for this reason that I regard it as too reductive to interpret his assistance as merely an instance of scheming or self-promotion. More important to him, I believe, was the opportunity to establish a counterexample to the case of the organization’s most famous source, US Army Private Chelsea Manning, whose thirty-five-year prison sentence was historically unprecedented and a monstrous deterrent to whistleblowers everywhere. Though I never was, and never would be, a source for Assange, my situation gave him a chance to right a wrong. There was nothing he could have done to save Manning, but he seemed, through Sarah, determined to do everything he could to save me. That said, I was initially wary of Sarah’s involvement. But Laura told me that she was serious, competent, and, most important, independent: one of the few at WikiLeaks who dared to openly disagree with Assange. Despite my caution, I was in a difficult position, and as Hemingway once wrote, the way to make people trustworthy is to trust them.

[snip]

It was only once we’d entered Chinese airspace that I realized I wouldn’t be able to get any rest until I asked Sarah this question explicitly: “Why are you helping me?”

She flattened out her voice, as if trying to tamp down her passions, and told me that she wanted me to have a better outcome. She never said better than what outcome or whose, and I could only take that answer as a sign of her discretion and respect.

It’s not just Snowden’s impression, though, that WikiLeaks intended to make an example of him. The superseding indictment against Assange cites several times when Assange invoked WikiLeaks’ role in Snowden’s successful escape to encourage others (including CIA Systems Administrators like Joshua Schulte, who had a ticket to Mexico when the FBI first interviewed him and seized his passports) to go do what Snowden did. British Judge Vanessa Baraitser even included one of those speeches in paragraphs distinguishing what Assange is accused of from legal journalism. And as early as 2017, public reporting said that WikiLeaks’ assistance to Snowden was what changed how DOJ understood WikiLeaks and why it began to consider prosecuting Assange. It wasn’t Trump that led DOJ to stop treating Assange as a journalist, it was Snowden.

According to Snowden’s own words, he shared WikiLeaks’ goal of setting an example to inspire others. In an email that Snowden must have sent Bart Gellman weeks before the exchange between him and Harrison above, Snowden described steps he took to give other leakers (this may be Gellman’s paraphrase), “hope for a happy ending.”

In the Saturday night email, Snowden spelled it out. He had chosen to risk his freedom, he wrote, but he was not resigned to life in prison or worse. He preferred to set an example for “an entire class of potential whistleblowers” who might follow his lead. Ordinary citizens would not take impossible risks. They had to have some hope for a happy ending.

To effect this, I intend to apply for asylum (preferably somewhere with strong internet and press freedoms, e.g. Iceland, though the strength of the reaction will determine how choosy I can be). Given how tightly the U.S. surveils diplomatic outposts (I should know, I used to work in our U.N. spying shop), I cannot risk this until you have already gone to press, as it would immediately tip our hand. It would also be futile without proof of my claims—they’d have me committed—and I have no desire to provide raw source material to a foreign government. Post publication, the source document and cryptographic signature will allow me to immediately substantiate both the truth of my claim and the danger I am in without having to give anything up. . . . Give me the bottom line: when do you expect to go to print?

Citizenfour also quotes Snowden describing how he hoped that proof that his “methods work[]” would encourage others to leak.

If all ends well, perhaps the demonstration that our methods worked will embolden more to come forward.

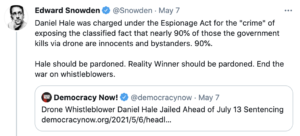

Snowden’s “methods” don’t work — they certainly haven’t for Daniel Hale, Reality Winner, or Joshua Schulte. But for each, Snowden played at least some role (there is ambiguity about how Schulte really felt about Snowden) in inspiring them to ruin their lives with magical thinking and inadequate operational security.

One of Snowden’s “methods” appears to entail quitting an existing job and then picking another at an Intelligence Community contractor with the intent of obtaining documents to leak. Snowden did this at Booz Allen Hamilton, and his book at least suggests the possibility he did that with his earlier job in Hawaii.

The government justified the draconian sentence that it had negotiated with Winner’s lawyers, in part, by claiming that she premeditated her leak.

Around the same time the defendant took a job with Pluribus requiring a security clearance in February 2017, she was expressing contempt for the United States, mocking compromises of our national security, and making preparations to leak intelligence information

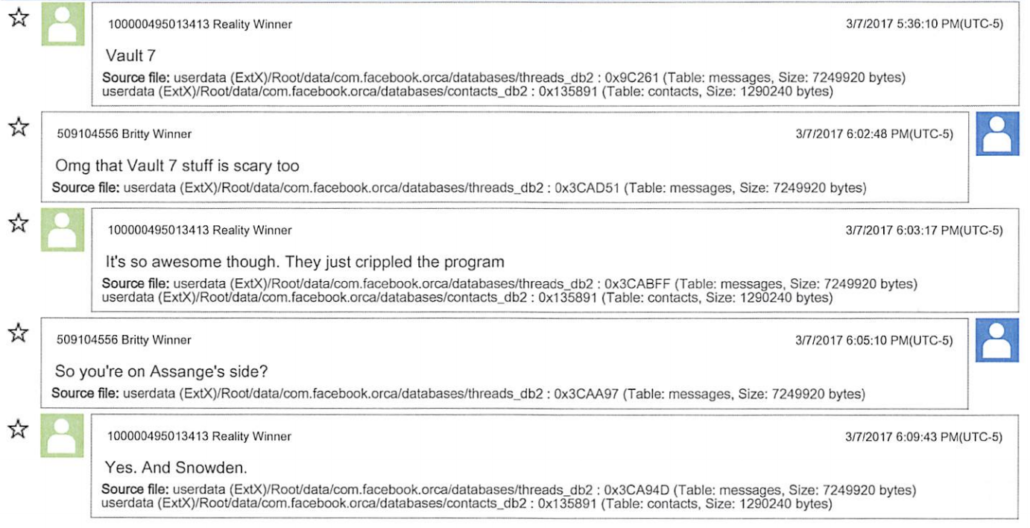

Along with evidence Winner researched The Intercept’s SecureDrop before starting at her new job, the government supported this claim by pointing to three references Winner made to Snowden as or shortly after she started at Pluribus, including texts in which Winner told her sister she was on Assange and Snowden’s side the day the Vault 7 leak was revealed. That was still two months before she took the files she would send to The Intercept.

Had Hale gone to trial, the government would have shown that Hale discussed serving as a source for Jeremy Scahill by May 30, 2013, the day before he left NSA, and discussed Snowden — and hanging out with the journalists reporting on him — the day Snowden came forward on June 9. Then, on July 25, Hale sent Scahill a resume showing he was looking for counterterrorism or counterintelligence jobs. In December, Hale started the the job at Leidos where he would print out the files he sent to The Intercept.

You can think these leaks were valuable and ethical without thinking it a good idea to leave a months-long trail of evidence showing premeditation on unencrypted texts and social media.

Similarly, one of Snowden’s “methods” was to claim he had expressed concerns internally, but was ignored, a wannabe whistleblower stymied by America’s admittedly failed support for whistleblowers, especially those at contractors.

In the weeks before Snowden left NSA, he made a stink about some legal issues and NSA’s training programs (about how FISA Section 702 interacted with EO 12333) that he subsequently pointed to as his basis for claiming to be a whistleblower. The complaint was legit, and one NSA department actually did take notice, but it was not a formal complaint; indeed, it was more a complaint about US law. But his complaint had nothing to do with the vast majority of the documents that have been published based off his files, to say nothing of the far greater set of documents he took. And he made the complaint long after having prepared for months to steal vast amounts of files.

Similarly, Joshua Schulte wrote two emails documenting purported concerns about CIA security, one to a colleague less than a month before he left, which he didn’t send, and then, on his final day, one to CIA’s Inspector General that he falsely claimed was unclassified, a copy of which he was seen taking with him when he packed up. In the first search warrant for Schulte’s house obtained on March 13, 2017, less than a week after the initial Vault 7 release, the FBI had already found those emails and deemed Schulte’s treatment of them as suspect. And when they found a copy of the classified letter to the IG stashed in his headboard, it gave them cause to seize Schulte’s passports on threat of arrest. Snowden’s “methods” didn’t deliver Schulte a “happy ending;” they made Schulte’s apprehension easier.

To the extent Schulte could be shown to be following Snowden’s “methods” (again, that question was not resolved at his first trial) it would be a fairly damning indictment of those methods, since this effort to create a paper trail as a whistleblower was such an obvious attempt to retroactively invent cover for leaks for which there was abundant evidence Schulte’s motivation was spite and revenge. Maybe that’s why someone close to Assange explicitly asked me to stop covering Schulte’s case.

Had Daniel Hale gone to trial, the government undoubtedly would have used the exhibits showing that Hale had never made any whistleblower claims in any of the series of government jobs where he had clearance as a way to push back on his claim of being a whistleblower, though Hale was outspoken about his criticisms of the drone program before he took most of the files he shared with The Intercept. Indeed, given the success of Hale’s earlier anti-drone activism, his case raises real questions about whether leaking was more effective than Hale’s frank, overt witness to the problems of the drone program.

Worse still, Snowden’s boasts about his “methods” appear to have made prosecutions more likely. An early, mostly-sealed filing in Hale’s case, reveals that the government set out to investigate whether Hale was The Intercept’s source because they were trying to figure out whom Snowden had “inspired” to leak.

Specifically, the FBI repeatedly characterized its investigation in this case as an attempt to identify leakers who had been “inspired” by a specific individual – one whose activity was designed to criticize the government by shedding light on perceived illegalities on the part of the Intelligence Community.

That explains why the government required Hale to allocute to being the author of an essay in a collection of Hale’s leaked documents involving Snowden: by doing so, they obtained sworn proof that Hale is the person Snowden and Glenn Greenwald were discussing, while the two were sitting in Moscow, in the closing sequence of Citizenfour. In the scene, Glenn flamboyantly wrote for Snowden how this new leaker and The Intercept’s journalist were communicating, what appears to be J-A-B-B-E-R. That stunt for the camera would have tipped the government off, in cinema release just two months after they had raided Hale’s home, to look for and reconstruct Hale’s Jabber communications with Jeremy Scahill, which they partly succeeded in doing.

Rather than being means to a “happy ending,” then, prosecutors have found Snowden’s “methods” useful to pursuing increasingly draconian prosecutions of people inspired by him.

And now, after Snowden and Greenwald failed to persuade Trump to pardon Snowden, Assange — and in a secondary effort — The Intercept’s sources (perhaps, like Assange, they find the association with Schulte counterproductive, because they didn’t even try to get him pardoned, even though Trump himself almost bolloxed that prosecution), Snowden is left demanding pardons on Twitter for the people he set out to convince leaking could have a “happy ending.”

By associating these leaks with someone being protected by Russia so that — in Snowden’s own words — he could encourage more leaks, Snowden only puts a target on these people’s back, making a justifiable commutation of Winner’s sentence less likely (Winner is due to get out on November 23, two days before the most likely time for Joe Biden to even consider commuting her sentence).

I’m grateful for Snowden’s sacrifices to release the NSA files, but his efforts to lead others to believe that leaking would be easy was bound to, and has, ended badly.

If Vladimir Putin agreed to protect Snowden in hopes that he would inspire more leakers to release files that help Russia evade US spying (as Schulte’s leak did, at a time when the US was trying to understand the full scope of what Russia had done in 2016), the US prosecutorial focus on Snowden-related leakers undermines his value to Putin, probably by design. As that happens, Snowden might reach the moment that observers of his case have long been dreading, the moment when Putin’s utilitarian protection of Snowden will give way to some other equally utilitarian goal.

This is all happening as Putin adjusts to dealing with Joe Biden rather than someone he could manipulate by (at the very least) feeding his narcissism, Donald Trump. It is happening in the wake of new sanctions on Russia, in response to which Putin put US Ambassador John Sullivan on a plane to deliver some message, in person, to Biden. It is happening as Biden’s response to the Colonial Pipeline attack, in which ransomware criminals harbored by Putin shut down US critical infrastructure for fun and profit, includes noting that he and Putin will meet in person soon, followed by the unexplained disabling of the perpetrators in the wake of the attack.

Meanwhile, even as Snowden is of less and less use to Putin, Glenn Greenwald’s utility continues to grow. Snowden, for example, continues to speak out about topics inconvenient to Putin, like privacy. The presence in Russia of someone like Snowden with his own platform and international credibility may become increasingly risky for Putin given the success of protests around Alexei Navalny.

Greenwald, by contrast, seems to have dropped all interest in surveillance and has instead turned many of his grievances — even his complaint that former NSA lawyer Susan Hennessey will get a job in DOJ’s National Security Division, against whom one can make a strong case on privacy grounds — into a defense of Russia. Greenwald spends most of his time arguing that a caricature that he labels “liberals” and another caricature that he labels “the [American] Deep State,” followed closely by another caricature he calls “the [non-right wing propaganda] Media,” are the most malignant forces in American life. In his rush to attack “liberals,” “the Deep State,” and “the Media,” Greenwald has coddled the political forces that Putin has found useful, including outright racists and other right wing extremists. By the end of the Trump presidency, Greenwald was excusing virtually everything Trump did, up to and including his attempted coup based on the utter denigration of democratic processes. In short, Greenwald has become a loud and important voice in support of the illiberalism Putin favors, to say nothing of Greenwald’s use of a rhetoric unbound by facts.

That Greenwald spends most of his days deliberately inciting Twitter mobs is just an added benefit, to those who want to weaken America, to Greenwald’s defense of fascists.

Most of us who used to know Greenwald attribute his Russian denialism and his apologies for Trump at least partly to his desire to free Snowden from exile. Yet Greenwald’s tantrums, because of their value to Putin, may have the opposite effect.

Stoking Greenwald’s irrational furor over what he calls “liberals” and “the Deep State” and “the Media” would actually be a huge incentive for Putin to deal Snowden to the US, in maximally symbolic fashion. There is nothing that could light up Greenwald’s fury like Putin bringing Snowden to a summit with Biden, wrapped up like a present, to send back on Air Force One. (That’s an exaggerated scenario, but you get my point.)

Plus, if Putin played it right, such a ceremonial delivery of Snowden might just achieve the completion of the Snowden operation, the public release of all of the files Snowden stole, not just those that one or another journalist found to have news value.

The Intelligence Community has, over the years, said a bunch of things about Snowden that were outright bullshit or, at least, for which they did not yet have evidence. But one true thing they’ve said is that Snowden took a great many files that had no imaginable privacy value. Even from a brief period working in the full archive aiming to answer three very discrete questions about FISA, I believe that to be true. While some (including Assange) pressured Snowden and others to release all these files, Snowden instead ensured that journalists would serve a vetting role, and after some initial fumbling, The Intercept did a laudable job of keeping those files safe. So up to now, the fact that Snowden took far more files than any privacy concern — even privacy concerns divorced from all question of nationality — could justify may not have mattered.

But as far as I know there are still full copies out there and Russia would love to spin up Glenn Greenwald’s fury so much he would attempt to burn down his caricature of “The Deep State” in retaliation — much like Schulte succeeded in badly damaging the CIA — by releasing his set.

I believe Russia has been trying to do this since at least 2016.

To be very clear, I’m not claiming that Greenwald is taking money from or is any way controlled by Russia. I am very much not claiming that, in part because it wouldn’t be necessary. Why pay Greenwald for what you can get him to do for free?

And while I assume Greenwald would respect Snowden’s stated wishes and protect the files, like Trump, Greenwald’s narcissism and resentment are very, very easy buttons to push. Greenwald has been heading in this direction without pushing. It would be child’s play to have people friendly to Russia’s illiberal goals (people like Steve Bannon or Tucker Carlson) exacerbate Greenwald’s anger at “the Deep State” to turn it into the frenzy it has become.

Meanwhile, custody of Edward Snowden would be a very enticing dangle for Putin to offer Biden as a way to reset Russia’s relationship with the US. One cannot negotiate with Putin, one can only adjust the points of leverage over each other and hope to come to some stable place, and Snowden has always been at risk of becoming a bargaining chip in such a relationship. By turning Snowden over to the US to be martyred in a high profile trial, Putin might wring the last bit of value out of Snowden. All the better, from Putin’s standpoint, if Greenwald were to respond by releasing the full Snowden set.

For the past four years, Greenwald seems to have believed that if he sucked up to Putin and Trump, he’d win Snowden’s freedom, as if either man would ever deal in good faith. Instead, I think, that process has had the effect of making Greenwald more useful to Russia than Snowden is anymore. And at this point, Greenwald seems to have lost sight of the likelihood that his belligerent rants may well make Snowden less safe, not more.

Update: According to the government sentencing memo for Hale, they didn’t write up the statement of offense, Hale did.

Hale pled guilty without any plea agreement, and submitted his own Statement of Facts. Def.’s Statement of Facts, Dkt. 197 (“SOF”).