Among those whinging that Merrick Garland hasn’t imprisoned Donald Trump yet, there is an apparent belief that the Mueller Report left obstruction charges all wrapped up in a bow, as if the next Administration could come in, break open the Report, and roll out fully-formed charges.

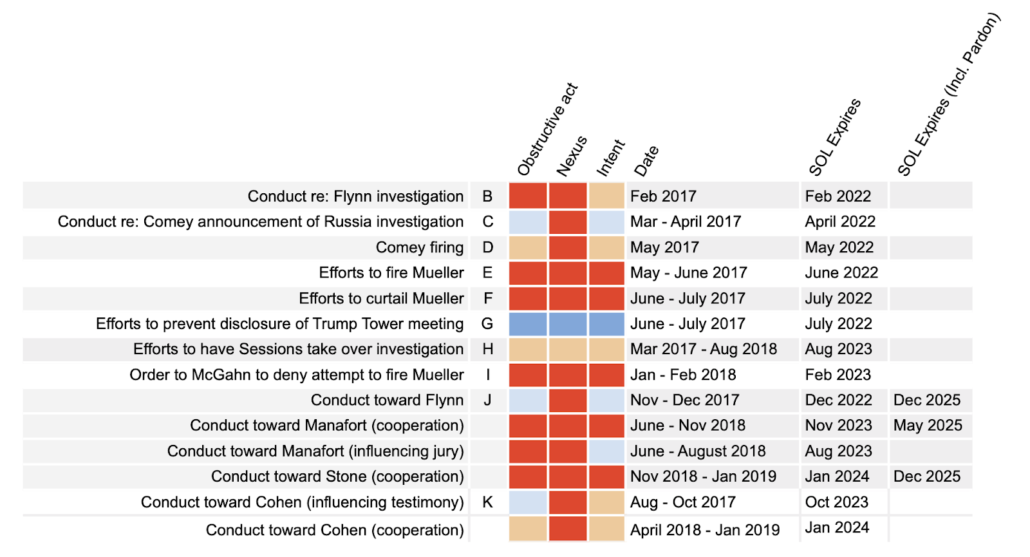

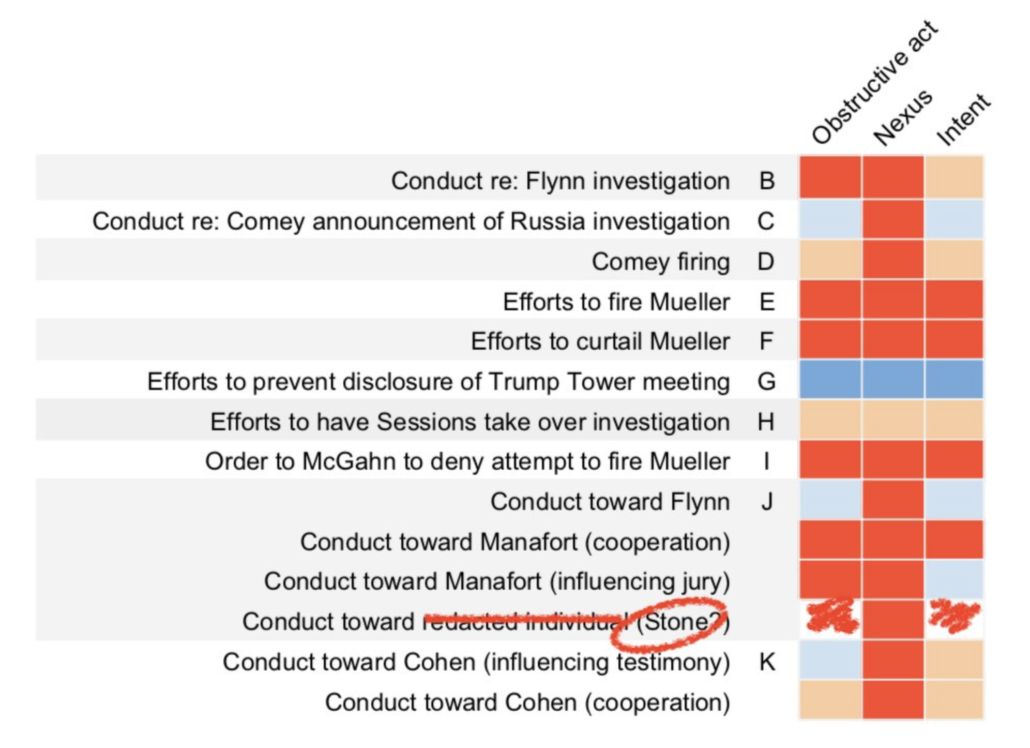

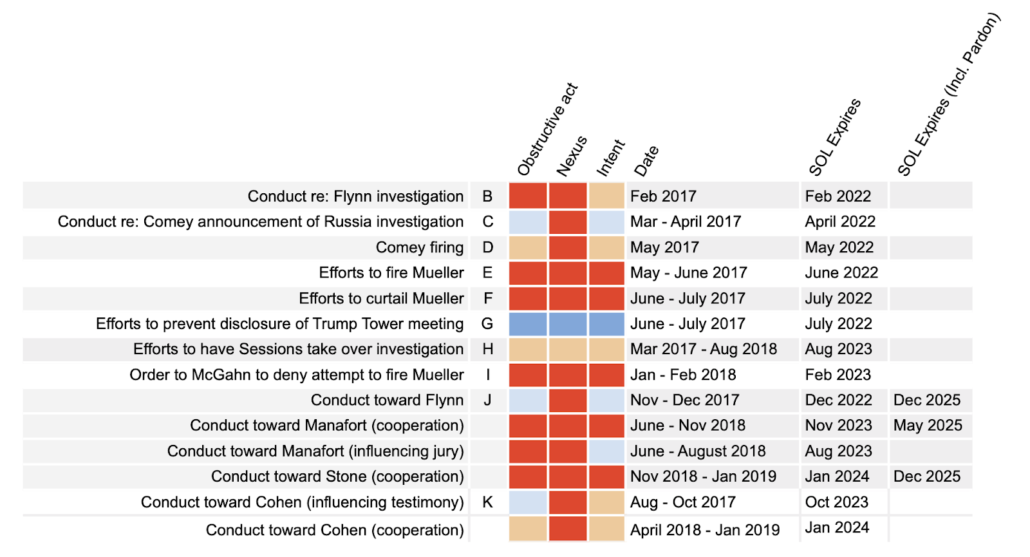

Even among those with a more realistic understanding of the Mueller Report, people continue to call for some public resolution of the obstruction charges, as Randall Eliason did here and Quinta Jurecic did here. Jurecic even updated her awesome heat map of the obstruction charges, with the date the statute of limitations (if an individual act of obstruction were charged outside a continuing conspiracy) would expire for each.

None of that is realistic, for a whole range of reasons.

The obstruction-in-a-box belief is based on a misunderstanding of the Mueller Report

First, the belief that Merrick Garland could have come into office 11 months ago and rolled out obstruction charges misunderstands the Mueller Report. Many if not most people believe the report includes the entirety of what Mueller found, describes declination decisions on every crime considered, and also includes a volume entirely dedicated to Trump’s criminal obstruction, a charging decision for which Mueller could not reach on account of the OLC memo prohibiting it. None of that is true.

As I laid out in my Rat-Fucker Rashomon series, the Mueller Report is only a description of charging decisions that the team made. My comparison of the stories told in the Report with those told in the Stone warrant affidavits, Stone’s trial, and the SSCI Report show that Mueller left out a great deal of damning details about Stone, including that he seemed to have advance notice of what the Guccifer 2.0 persona was doing and that Stone was scripting pro-Russian tweets for Trump in the same period when Trump asked Russia, “if you’re listening — I hope you are able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing.”

And, as DOJ disclosed hours before the 2020 election, Mueller didn’t make a final decision about whether Stone could be charged in a hack-and-leak conspiracy. Instead, he referred that question to DC USAO for further investigation. In fact the declinations in the Mueller Report avoid addressing any declination decision for Stone on conspiring with Russia. The declination in the report addresses contacts with WikiLeaks (but not Guccifer 2.0) and addresses campaign finance crimes. The section declining to charge any Trumpsters with conspiracy declines to charge the events described in Volume I Section II (the Troll operation) and Volume I Section IV (contacts with Russians), in which there is no Stone discussion. Everything Stone related — even his contacts with Henry Greenberg, which is effectively another outreach from a Russian — appears in Section III, not Section IV. The conspiracy declinations section doesn’t mention Volume I Section III (the hack-and-leak operation) at all and (as noted) in the section that specifically addresses hack-and-leak decisions, a footnote states that, “Some of the factual uncertainties [about Stone] are the subject of ongoing investigations that have been referred by this Office to the D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office.” This ongoing investigation would have been especially sensitive in March 2019, because prosecutors knew that Stone kept a notebook recording all his conversations with Trump during the campaign, many of which (they did have proof) pertained to advance notice of upcoming releases. That is, the ongoing investigation into Stone was also an ongoing investigation into Trump, which is consistent with what Mueller told Trump’s lawyers in summer 2018.

That’s not the only investigation into Trump that remained ongoing at the time Mueller closed up shop. The investigation into a suspected infusion of millions from an Egyptian bank during September 2016 continued (per CNN’s reporting) until July 2020, which is why reference to it is redacted in the June 2020 Mueller Report but not the September 2020 one. I noted both these ongoing investigations in real time.

The Mueller Report also doesn’t address the pardon discussions with Julian Assange, even though that was included among Mueller’s questions to Trump.

So contrary to popular belief, Volume II does not address the totality of Trump’s criminal exposure.

That ought to change how people understand the obstruction discussion in Volume II. For all the show of whether or not Mueller could make a charging decision about Trump, the discussion provably did not include the totality of crimes Mueller considered with Trump.

All the more so given the kinds of obstructive acts described in Volume II. The biggest tip-off that this volume was about something other than criminal obstruction charges, in my opinion, is the discussion of Trump’s lies about the June 9 meeting in Trump Tower. As Jurecic’s heat map, her extended analysis, and my own analysis at the time show, the case that this was obstruction was weak. “Mueller spent over eight pages laying out whether Trump’s role in crafting a deceitful statement about the June 9 meeting was obstruction of justice when, according to the report’s analysis of obstruction of justice, it was not even a close call.” At the time, I suggested Mueller included it because it explained what Trump was trying to cover up with his other obstructive actions during the same months. But I think the centrality of Vladimir Putin involvement in Trump’s deceitful statement — which gets no mention in the Report, even though the Report elsewhere cites the NYT interview where that was first revealed — suggests something else about this incident. Because of how our Constitution gives primacy in foreign affairs to the President, DOJ would have a very hard time charging the President for conversations he had with a foreign leader (Trump’s Ukraine extortion was slightly different because Trump refused to inform Congress of his decision to blow off their appropriation instructions). But Congress would (in a normal time, should) have no difficulty holding the President accountable for colluding with a foreign leader to invent a lie to wield during a criminal investigation. Trump’s June 9 meeting lie is impeachable; it is not prosecutable.

Similarly, several of the other obstructive acts — asking Comey to confirm there was no investigation into him, firing Comey, and threatening to fire Mueller — would likewise be far easier for Congress to punish than for DOJ to, because of how expansively we define the President’s authority.

That is, these ten obstructive acts are best understood, in my opinion, as charges for Congress to impeach, not for DOJ to prosecute. The obstruction section — packaged up separately from discussion of the other criminal investigations into Trump — was an impeachment referral, not a criminal referral. I think Mueller may have had a naive belief that Congress would be permitted to consider those charges for impeachment, such an effort would succeed, and that would leave DOJ free to continue the other more serious criminal investigation into Trump.

It didn’t happen.

But that doesn’t change that a number of these obstructive acts are more appropriate for Congress to punish than for DOJ to.

Bill Barr did irreparable damage to half of these obstruction charges

Bill Barr, of course, had other things in mind.

Those wailing that Garland is doing nothing in the face of imminently expiring obstruction statutes of limitation appear to have completely forgotten all the things Billy Barr did to make sure those obstruction charges could not be prosecuted as they existed when Mueller released his report.

That effort started with Barr’s declination of the obstruction charges.

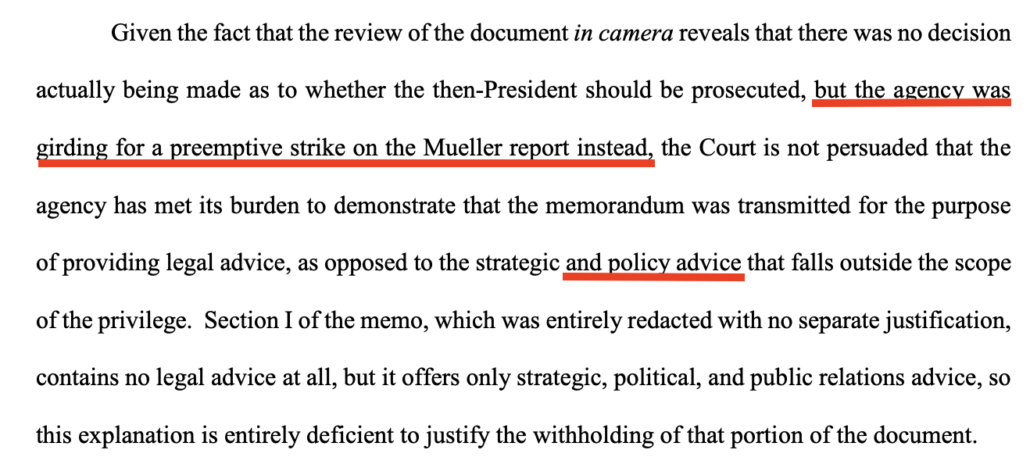

Last year, Amy Berman Jackson forced DOJ to release part of the memo Barr’s flunkies wrote up the weekend they received the Mueller Report. The unsealed portions show that Rod Rosenstein, Ed O’Callaghan, and Steven Engel signed off on the conclusion that,

For the reasons stated below, we conclude that the evidence described in Volume II of the Report is not, in our judgment, sufficient to support a conclusion beyond a reasonable doubt that the President violated the obstruction-of-justice statutes. In addition, we believe that certain of the conduct examined by the Special Counsel could not, as a matter of law, support an obstruction charge under the circumstances. Accordingly, were there no constitutional barrier, we would recommend, under the Principles of Federal Prosecution, that you decline to commence such a prosecution.

This was unbelievably corrupt. There are a slew of reasons — from Barr’s audition memo to the way these officials include no review of the specific allegations to the fact that some of these crimes were crimes in progress — why this decision is inadequate. But none of those reasons can make the memo go away. So unless DOJ were to formally disavow this decision after laying out the reasons why the process was corrupt (preferably via analysis done by a quasi-independent reviewer like the Inspector General), any prosecution of the obstruction crimes laid out in the Mueller Report would be virtually impossible, because the very first thing Trump would do would be to cite the memo and call these three men as witnesses that the case should be dismissed.

But Barr’s sabotage of these charges didn’t end there. At his presser releasing the heavily-redacted report, Barr excused Trump’s obstruction because (Barr claimed) Trump was very frustrated he didn’t get away with cheating with Russia unimpeded, thereby deeming his motives to be pure.

In assessing the President’s actions discussed in the report, it is important to bear in mind the context. President Trump faced an unprecedented situation. As he entered into office, and sought to perform his responsibilities as President, federal agents and prosecutors were scrutinizing his conduct before and after taking office, and the conduct of some of his associates. At the same time, there was relentless speculation in the news media about the President’s personal culpability. Yet, as he said from the beginning, there was in fact no collusion. And as the Special Counsel’s report acknowledges, there is substantial evidence to show that the President was frustrated and angered by a sincere belief that the investigation was undermining his presidency, propelled by his political opponents, and fueled by illegal leaks. Nonetheless, the White House fully cooperated with the Special Counsel’s investigation, providing unfettered access to campaign and White House documents, directing senior aides to testify freely, and asserting no privilege claims. And at the same time, the President took no act that in fact deprived the Special Counsel of the documents and witnesses necessary to complete his investigation. Apart from whether the acts were obstructive, this evidence of non-corrupt motives weighs heavily against any allegation that the President had a corrupt intent to obstruct the investigation.

These claims were, all of them, factually false, as I laid out at the time. But because he was the Attorney General when he made them, they carry a great deal of weight, legally, in establishing that Trump had no corrupt motive for obstructing the investigation into his ties to Russia.

And after that point, Barr made considerable effort to manufacture facts to support his bullshit claims. Most obviously, he sicced one after another after another investigator on the Russian investigation to try to substantiate his own bullshit claims. In the case of Barr’s efforts to undermine the Mike Flynn prosecution — which investigation lies behind four of the obstruction charges laid out in the Mueller Report — the Jeffrey Jensen team literally altered documents to misrepresent the case against Flynn. Similarly, a Barr-picked prosecutor installed to replace everyone who was fired or quit in the DC US Attorney’s Office, Ken Kohl, stood before Judge Sullivan and claimed (falsely) that everyone involved with the Flynn prosecution had no credibility.

If we move forward in this case, we would be put in a position of presenting the testimony of Andy McCabe, a person who our office charged and did not prosecute for the same offense that he’s being — that we would be proceeding to trial against with respect to Mr. Flynn.

So all of our evidence, all of our witnesses in this case as to what Mr. Flynn did or didn’t do have been — have had specific findings by the Office of Inspector General. Lying under oath, misleading the Court, acting with political motivation. Never in my career, Your Honor, have I had a case with witnesses, all of whom have had specific credibility findings and then been pressed to go forward with the prosecution. We’re never expected to do so.

Again, so long as this testimony remains credible, you can’t pursue obstruction charges remotely pertaining to Flynn, meaning four of the obstruction charges are off the table.

Barr also chipped away at the other charges underlying the obstruction charges, intervening to make it less likely that Roger Stone or Paul Manafort would flip on Trump and help DOJ substantiate that, yes, Trump really did cheat with Russia to get elected. Barr also got OLC to undercut the analysis behind charging Michael Cohen for the hush payments (which may have made it impossible for SDNY to charge Trump with the same charges).

Meanwhile, John Durham toils away, trying to build conspiracy charges to substantiate the rest of Barr’s conspiracy theories. Along the way, Durham seems to be tainting other evidence that would be central to any obstruction charges against Trump. For example, in the most recent BuzzFeed FOIA release, all parts of Jim Comey’s memos substantiating Trump’s obstruction that mentioned the Steele dossier were protected under a b7(A) exemption, which is almost certainly due to Durham’s pursuit of a theory that Trump’s actions with Comey were merely a response to the Steele dossier, not an attempt to hide his Flynn’s very damning conversations with the Russian Ambassador during the transition. That is, Durham is as we speak making evidence unavailable in his efforts to invent facts to back Barr’s claims about Trump’s pure intent in obstructing the Mueller investigation.

As noted, all of these efforts are fairly self-obviously corrupt, and most don’t withstand close scrutiny (as the altered documents did not when I pointed them out). But before DOJ could pursue the obstruction charges as they existed in the Mueller Report, they would first have to disavow all of this.

Inspector General Michael Horowitz was reportedly investigating at least some of this starting in 2020. And I trust his investigators would be able to see through much of what Barr did. But even assuming Horowitz was investigating the full scope of all of them, because of the pace of DOJ IG investigations, the basis to disavow Barr’s efforts would not and will not come in time to charge those obstruction counts before the statutes of limitation expires.

The continuing obstruction statutes have barely started

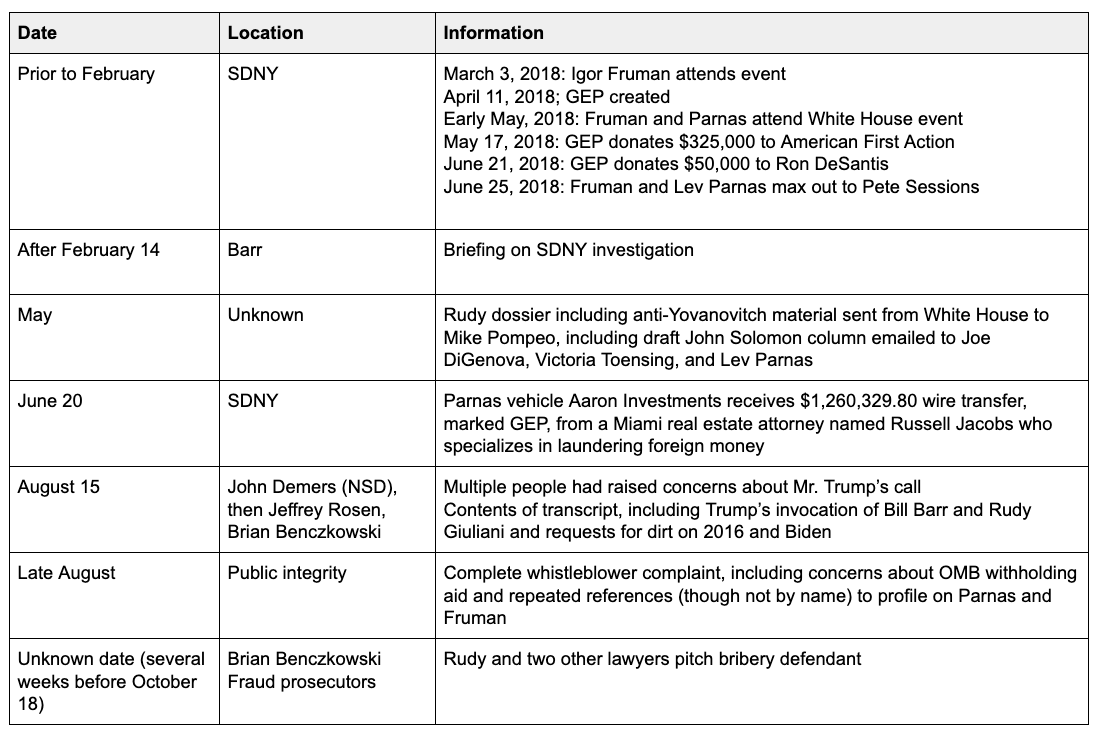

In addition to obstructing the punishment of Paul Manafort and Roger Stone and undermining the theory behind the Michael Cohen hush payment charges, Bill Barr also worked relentlessly to undermine the prosecution of Rudy Giuliani.

There were undoubtedly a lot of reasons Barr needed to do that. If he didn’t, he might have to treat Trump’s extortion of Ukraine (which was the follow-up to Manafort’s Ukraine ties in 2016). Rudy was central to Trump’s own obstruction of the Mueller investigation. And if Rudy were shown to be an Agent of Russian-backed Ukrainians, it would raise significant questions about Trump’s larger defense (questions for which there is substantiation in Mueller’s 302s).

I understand there was a sense, in the middle of Barr’s efforts, that prosecutors believed they could just wait those efforts out.

And then, literally on Lisa Monaco’s first day on the job, DOJ obtained warrants to seize 16 devices from Rudy. During all the months that people have been wailing for Garland to act, Barbara Jones has been wading through Rudy’s phones to separate out anything privileged (and, importantly, to push back on efforts to protect crime-fraud excepted communications). Almost the first thing Lisa Monaco did was approve an effort to go after the key witness to the worst of Trump’s corruption.

There are many reasons I keep coming back to that seizure to demonstrate that Garland’s DOJ (in reality, Monaco would be the one making authorizations day-to-day) will not back off aggressive investigations of Trump. Even if DOJ only had warrants for the Ukraine investigation, it would still get to larger issues of obstruction, because of how it relates to impeachment. But even if it were true those were the only warrants when DOJ raided Rudy, there’s abundant reason to believe that’s no longer true. If DOJ got warrants covering the earlier obstruction or Rudy’s role in the attempted coup, no one outside that process would know about it.

Then, in recent days, DOJ made another audacious seizure of a lawyer’s communications, a seizure that only makes sense in the context of a larger obstruction investigation, this time of the January 6 investigation, yet more evidence that DOJ it not shying away from investigating Trump’s crimes.

Indeed, DOJ currently has investigations into all the nodes of the pardon dangles, too: Sidney Powell’s work for Trump on a thing of value (the Big Lie) while waiting for a Mike Flynn pardon; Roger Stone’s coordination with militias before and after he got his own pardon; promises to the Build the Wall crowd — promises kept only for Bannon — tied to efforts to help steal the election; and Rudy’s role at the center of all this.

There would be no reason to charge the pardon dangles from 2019 (the balance of the obstruction charges that Barr didn’t hopelessly sabotage) when DOJ has more evidence about pardon bribes from 2020, including the devices of the guy at the center of those efforts, and the direct tie to the January 6 coup attempt to tie it to. Indeed, attempting to charge the earlier dangles without implicating everything Trump got out of the pardons in his attempted coup would likely negatively impact an investigation into the more recent actions.

Even assuming Mueller packaged obstruction charges for DOJ to indict, rather than Congress to impeach, the deliberate sabotage Barr did in the interim makes most of those charges impossible. The exceptions — the pardon dangles — all have additional overt acts to include that sets aside Barr’s past declination.

DOJ cannot charge the Mueller obstruction charges. But they also cannot explain why not, partly because of the institutional necessity to move beyond Barr’s damage, but partly because doing so would damage the possibility of charging the continuation of that very same obstruction.

One obstruction crime is actually a conspiracy crime

I forgot one more detail that’s really important: One of the listed acts of obstruction, Trump’s efforts to have Jeff Sessions shut down the investigation, appears to be a Stone-related conspiracy crime. As I noted, that effort started nine days after Roger Stone told Julian Assange, “I am doing everything possible to address the issues at the highest level of Government.”

Especially given that it is among the weaker obstruction crimes, this is one that would be better pursued as a conspiracy crime (though it would be tangled up in the Assange extradition).

Update: As Jackson noted on Twitter, DC Circuit should soon weigh in on ABJ’s efforts to liberate more of Barr’s declination memo.