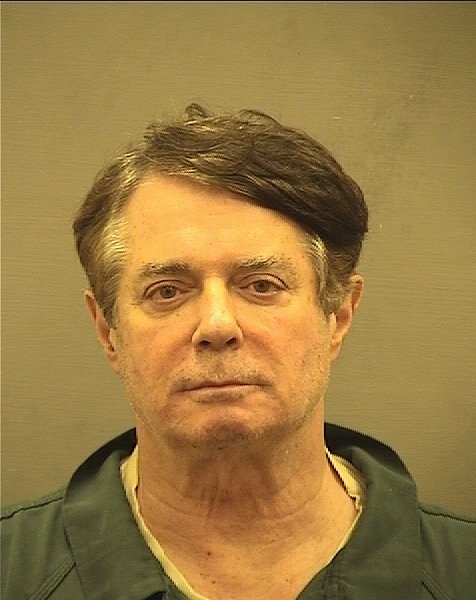

A Newfound Obsession with Paul Manafort’s iCloud Account

There was an interesting filing last week in the case of Stephen Calk, the banker charged with giving Paul Manafort a loan in exchange for a position in the Trump Administration. It is probably totally innocent, but it reveals certain things about referrals from the Mueller investigation. And given my past obsession with Manafort’s OpSec (or, more commonly, lack thereof) dealing with Apple products, I’m intrigued that the contents of one imaging of Manafort’s iCloud account remained outside normal evidentiary filing systems.

Calk’s lawyers have long pushed prosecutors in SDNY for more expansive discovery relating to Manafort and his son-in-law. In a filing in April, they described that the investigations of Manafort and Calk proceeded in close parallel, and so there might be Mueller files that were pertinent to Calk.

Beginning in or about March 2017, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York and the Special Counsel’s Office (“SCO”), commenced a joint investigation that ultimately led to the indictment of Mr. Calk in this case. The SCO, which was investigating former Trump Campaign Chairman Paul Manafort, and Southern District (including the prosecutors on this case) worked closely together, conducted joint proffer sessions with employees of Mr. Calk’s bank (The Federal Savings Bank (“TFSB”)), and from early on shared evidence and information. Indeed, the investigation of Mr. Calk was totally intertwined with the SCO’s investigation of Manafort; the two investigations even shared the same FBI case agent. Manafort was charged in February 2018 with defrauding TFSB (among other banks) by providing the bank with false information about his finances in connection with the two loans at the heart of the case against Mr. Calk (loans that, in this case, the government now claims were obtained through bribery rather than deception). At Manafort’s trial in August 2018, two TFSB employees testified for the government pursuant to immunity orders regarding those loans. Those same witnesses, as well as potentially others from the Manafort trial, are expected to testify at Mr. Calk’s trial. There will also be substantial overlap of documentary evidence.

From the outset of this case, the government was thus well aware that it would need to review the files of the Special Counsel’s Office for relevant Rule 16 materials.

[snip]

On July 29, 2019, the defense sent a discovery letter to the government seeking discovery pursuant to Rule 16 and Brady/Giglio, and specifically reminding the government of its obligation to review the files of the SCO for responsive material. Prior to the August 26 deadline, the government made six productions to the defense totaling approximately 90,000 documents (approximately 1,265,000 pages). 1 Yet, according to the government’s index accompanying the discovery, none of the six sets appears to have included materials from the files of the Special Counsel’s Office.

On August 26, 2019, the government sought permission of the Court to extend the discovery deadline to October 15, 2019. (ECF No. 28). The government explained that it had “completed its production of discoverable materials from [its own] investigative files,” but that it had “been obtaining materials from the files of investigations conducted by the Central District of California and the Special Counsel’s Office . . . , and ha[d] begun reviewing and producing such materials.” (Id.). The government noted that, while it believed “its production of core Rule 16 discovery material [was] substantially complete, . . . there [was] a significant volume of additional material from the files of the Special Counsel’s Office—some of which [was] not yet in [the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York’s] possession—that the Government intend[ed] to review for production to the defense” and therefore required an “extension of the discovery deadline by several weeks.”

In response to that filing the government described what sounded like a kind of graymail on the part of Calk’s lawyers, discovery requests that had nothing to do with the case against Calk, but which might elicit sensitive files about the Mueller investigation, including details of anything the government ever considered charging Manafort with.

For example, notwithstanding the fact that Manafort is not a named defendant in this case and is not a likely trial witness for the Government, the defense has asked broadly for the entire contents of all email accounts used by Manafort (without any restrictions based on, for example, time period or who Manafort used these accounts to correspond with), Ex. B at 5; all documents and communications “concerning any entities controlled directly or indirectly by, or associated with, Mr. Manafort or Mr. Yohai or their family members,” Ex. B at 4 (which would appear on its face to call broadly for every record concerning any of Manafort’s lobbying or consulting businesses throughout his entire career and concerning every activity he conducted as part of any such business during his career—as well as the same for, among others, Manafort’s adult children); and all documents concerning any offense by Manafort “investigated or considered” by the Government (which would would seem to encompass virtually any document in the SCO’s file if not narrowed, as Calk’s counsel never agreed to do), Ex. A. at 2, even though that material was not gathered by this Office as part of this investigation and virtually none of that material has anything to do with (or was ever known to or sought by) Calk or the Federal Savings Bank. [my emphasis]

The government’s filing actually makes it clear that the two investigations proceeded with totally separate sets of evidence, with the Mueller evidence inaccessible to the Calk team.

Last Friday, the government informed the court that they were still finding Mueller-related files and providing them to Calk.

Last week, in the process for searching for additional material requested by the defendant, the Government discovered that it had inadvertently failed to previously identify and produce a limited universe of additional materials from SCO’s Manafort files. Although a very limited number of these materials may be of some relevance to this case, the vast majority of these materials appear upon the Government’s limited initial inspection to be either duplicative of prior productions or of minimal relevance. Nonetheless, the Government is producing these materials immediately out of an abundance of caution and undertaking efforts to minimize delay and disruption to the defense by (i) identifying the documents within the new production that are most likely to be relevant; and (ii) undertaking a substantial technical effort, at the Government’s expense, to de-duplicate the new materials against prior productions so as to help defense counsel quickly identify any documents that are truly new. As also described below, in light of our discovery of this new material, the Government is also undertaking a broader re-review of the Manafort Materials to ensure that nothing else in the Manafort Materials has been overlooked. As also detailed herein, we expect that process to be completed well in advance of the current December 2020 trial date.

The files include documents from Calk’s bank that the bank did not turn over in response to subpoenas from SDNY (but did turn over to Mueller’s team).

Specifically, in its review of this subset of the material thus far, the Government has identified fewer than 100 documents that appear to be potentially relevant and non-duplicative, including certain files that were apparently produced by The Federal Savings Bank (“TFSB”) to the USAO CDCA and the Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section (“MLARS”) as part of their investigations3 but not to the Government in this case. 4

3 MLARS had been conducting an investigation of Manafort prior to the formation of SCO.

4 Certain of these files, which would have already been available to the defendant due to his control and majority ownership of TFSB, appear responsive to the Government’s subpoenas to TFSB, and it is not clear why they were not produced to the Government as part of this investigation.

The more interesting detail is that some of the Manafort files — including recordings of his jail conversations and the contents of his iCloud account — were not uploaded to the FBI system.

The discovery of the 30,000 uncategorized Manafort-related files described above also led the Government to further review SCO’s discovery productions to Manafort to ensure that no additional materials had been inadvertently overlooked. The Government had previously understood, based on extensive communications with members of the SCO team and its own review of the SCO’s file storage system, that, with several immaterial exceptions, the SCO discovery productions to Manafort were drawn from the sources that the Government had independently searched, including the FBI’s files as described above. However, after further reviewing the SCO’s discovery transmittal letters and copies of certain of the SCO’s productions, the Government has realized that certain discovery that had been produced to Manafort was apparently not contained within the sources the Government had searched in this case.7 Included within this set of additional material is certain material that appears to be potentially relevant (in particular, a small set of TFSB documents that, again, would already be available to the defendant but that were not produced to the Government in this case) and a much more substantial universe of material that appears unlikely to be relevant (such as Manafort’s recorded jail calls, and documents associated with depositions, including of Manafort, in a 2015 civil lawsuit). Again, as with the 30,000 documents described above, the Government will be producing virtually all of these materials to the defense consistent with the broad approach it has taken to the Manafort Materials to date. We currently expect to transmit these materials to the defense within the next week.8

7 The Government is very grateful to the former SCO personnel for their extensive assistance in the Government’s efforts to locate and produce the Manafort Materials in this case, and while noting these communications to put the Government’s efforts to date in context, the Government certainly does not intend to suggest fault or blame for what may well have been the Government’s misunderstanding or mistake.

8 The volume of these materials is under 20 gigabytes, consisting of 53 recorded jail calls, one iCloud account extraction that the Government believes contains negligible information related to Calk, three video depositions, and several thousand pages of documents. The Government believes they are likely largely non-duplicative of its previous productions, but will attempt to deduplicate these documents as described herein and inform the defense of the results of this process. [my emphasis]

We know from his plea breach proceedings that Manafort continued to be investigated long after he was jailed, and we know from filings about his conduct in jail that he attempted to communicate in ways that evaded monitoring systems.

Yet some of that information, it appears, remained (and remains) segregated from generally accessible filing systems at DOJ.

That has implications for any FOIA responses — but it also has implications for any effort by Billy Barr to assess what the universe of evidence against Manafort is. For over a year after the end of the Mueller investigation, this material has been somewhere else, inaccessible to normal searches on DOJ systems.