The Search For The Origins Of The State

Related posts

Posts on The Dawn Of Everything: Link

Posts on Pierre Bourdieu and Symbolic Violence: link

Posts trying to cope with the absurd state of political discourse: link

Posts on Freedom and Equality. link

In Chapter 10 of The Dawn Of Everything the authors, David Graeber and David Wengrow, take up the search for the origins of the state. They discuss current theories of the nature of the state. They provide a different framework for understanding the term in ancient times, and even suggest that the earliest versions of these organizational structures were part-time, just as agriculture was part-time. Then they give examples of how their theory works.

Theories of the State

Today almost everyone lives under the governance of a nation-state. The generally accepted definition was suggested by Rudolph von Ihering in the late 1800s and is now associated with Max Weber: “… any institution that claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of coercive force within a given territory….” P. 359. But that’s not the way things worked in the earliest large groups.

Marxists suggested that states emerged to protect the power of an emerging ruling class, but the authors reject this theory.

A third theory is quite common: as the population in any area increases, you need top-down authority to coordinate and plan. But, as we’ve seen, this isn’t right, because a large number of ancient polities operated quite well without an autocratic leader endowed with the power of violence.

The authors suggest that at least for ancient societies we should consider three factors:

- Sovereignty, meaning the control of violence directed at members of the group and the right to authorize other to inflict violence;

- Administration, meaning control over information. This can be of two kinds. Frequently it means factual information necessary to keep things operating, for example taxes due and collected, or corvée obligations. Particularly in early societies it means esoteric or cultic knowledge, for example, explanations of the cosmos and the roles of people in it.

- Charisma, meaning a personal power of persuasion that enables one to dominate others.

Each of these factors is a form of dominance, which the authors see as the basis of the state. The authors rephrase the search for the origins of the state from their perspective:

How did large-scale forms of domination first emerge, and what did they actually look like? What, if anything, do they have to do with arrangements that endure to this day? P. 370.

Dominance in early societies

This material takes up most of the chapter. The authors give examples of societies organized under one form of dominance, which they call First-Order Societies, then societies with two of the forms of dominance, Second-Order Societies. The material is fascinating, and the examples support the use of their categories. I’m only going to discuss one illustration, the Chavin Culture, a pre-Inca group located on the western slopes of the Andes down to the sea near what is now Lima Peru.

This culture seems to have arisen around 3000 BCE, and flowered around 1200 BCE. It lasted another 800 years before disappearing. The authors say there is little evidence of the use of violence, no evidence of a formal bureaucracy, and no evidence of a monarch with sovereign or political power.

The archaeological record is dominated by imagery, primarily carved stone. Here’s a description.

Crested eagles curl in on themselves, vanishing into a maze of ornament; human faces grow snake-like fangs, or contort into a feline grimace. No doubt other figures escape our attention altogether. Only after some study do even the most elementary forms reveal themselves to the untrained eye. With due attention, we can eventually begin to tease out recurrent images of tropical forest animals – jaguars, snakes, caimans – but just as the eye attunes to them they slip back from our field of vision, winding in and out of each other’s bodies or merging into complex patterns. P. 388.

The authors characterize these as “shamanic journeys to the world of chthonic spirits and animal familiars.” The society was held together by rituals and cultic knowledge. The people seem to have enjoyed rituals oriented to hallucinogenic substances made from local plants.

This is an example of a First-Order Society.

Discussion

1. I do like the idea of a stoner kingdom.

2. The authors possibly think that societies are held together through domination. Like power, this is a term they don’t discuss. I did a digression on power, link above. I’ve discussed Pierre Bourdieu’s work on domination, link above. And I’ve discussed some current ideas about freedom, which is the complement to the idea of both, link above.

But they give plenty of examples where that isn’t so. In fact, they seem to think we’d be better off if we lived without domination, or at least in a society where decisions are made in a more democratic system. That contradiction is confusing.

3.

Very large social units are always, in a sense, imaginary. Or, to put it in a slightly different way: there is always a fundamental distinction between the way one relates to friends, family, neighbourhood, people and places that we actually know directly, and the way one relates to empires, nations and metropolises, phenomena that exist largely, or at least most of the time, in our heads. P. 276.

Large social units may exist in the imagination, but they have roots in reality. I live in the Gold Coast neighborhood of Chicago. I only know a few of my neighbors, but we are bound together by a number of links. We care about local schools, local traffic, local businesses and our parks in a particular way. If these are threatened, say by a local developer trying to replace a park or increase the traffic burden, we cooperate to deal with it.

I’m bound to other Chicagoans by crucial ties: they staff my doctor’s office, my dry cleaner, and my grocery store, and everything else I need. My life is smooth and pleasant because of them. I care that they are safe and healthy. I care that they have paved streets so they can get to work, and so I care about the people who pave those streets, clear off the snow, fill the potholes, and replace the bulbs in the stoplights. I want everybody’s kids to have good schools, just like I want good schools for my grandkids.

We have other ties. We like brats and argue about pizza. We ride public transport and we talk about the best way to get around in our miserable traffic. We go to movies, theater, concerts, and restaurants together. We can always talk about something here that affects us all, the latest corruption story, property taxes, who the Bears should draft, and the weather.

As I read it, the authors think those ties are strong enough to pull us together as a group without a dominating force.

4. Each of the societies described in the book has a mental component that goes deeper than just being neighbors. They share rituals, cosmologies, stories about themselves as a people, cultic practices, and there’s a shared understanding of themselves as a group. These are taught to children and reinforced by ritual and practice throughout the lives of members. They are at least as important to the maintenance of the group as any of the forms of dominance.

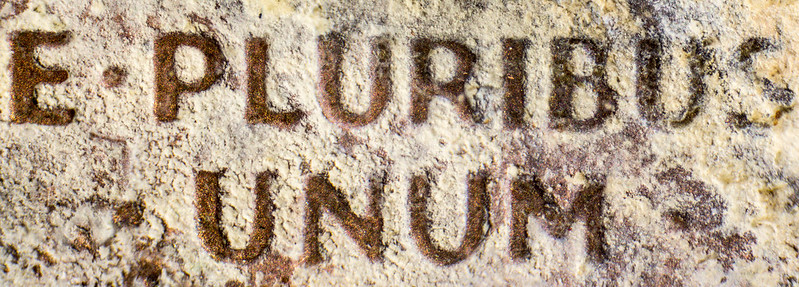

The Founders rejected the idea of a state religion, and we’ve mostly abandoned cultic practices. I think we Americans share a sort of secular religion based on the founding myths of our country and a weak allegiance to what Jefferson called “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God” in the Declaration of Independence. The latter is a formulation that originally meant Natural Law but I think now includes a science-based mental stance and values based on a vaguely Christian moral sense. The founding myths include our commitment to freedom, as “all men are created equal”; a government of laws, not of men; a form of capitalism; and representative democracy.

This, roughly, is the mental component that up til now has bound us into a nation. I think the authors miss this point.

======

Photo credit: Cbrescia.