Michigan Is Using More a Pessimistic Model than the White House

On Monday, the CEO of Spectrum Health, Tina Freese Decker, sent out an update on COVID-19. After explaining how they’re modeling the virus, she said that the model they’re using says our peak (presumably meaning Grand Rapids and environs, not Michigan as a whole) would be in early May.

[W]e are closely studying our models, which include learnings and data from across the state, country and world. These models project the spread of COVID-19 and enable us to estimate how many people in our communities will need hospitalization and intensive care services. They also allow us to understand the collective resources that would then be necessary to serve those needs. These are just estimates and we hope for the best, but our job is to plan for the worst.

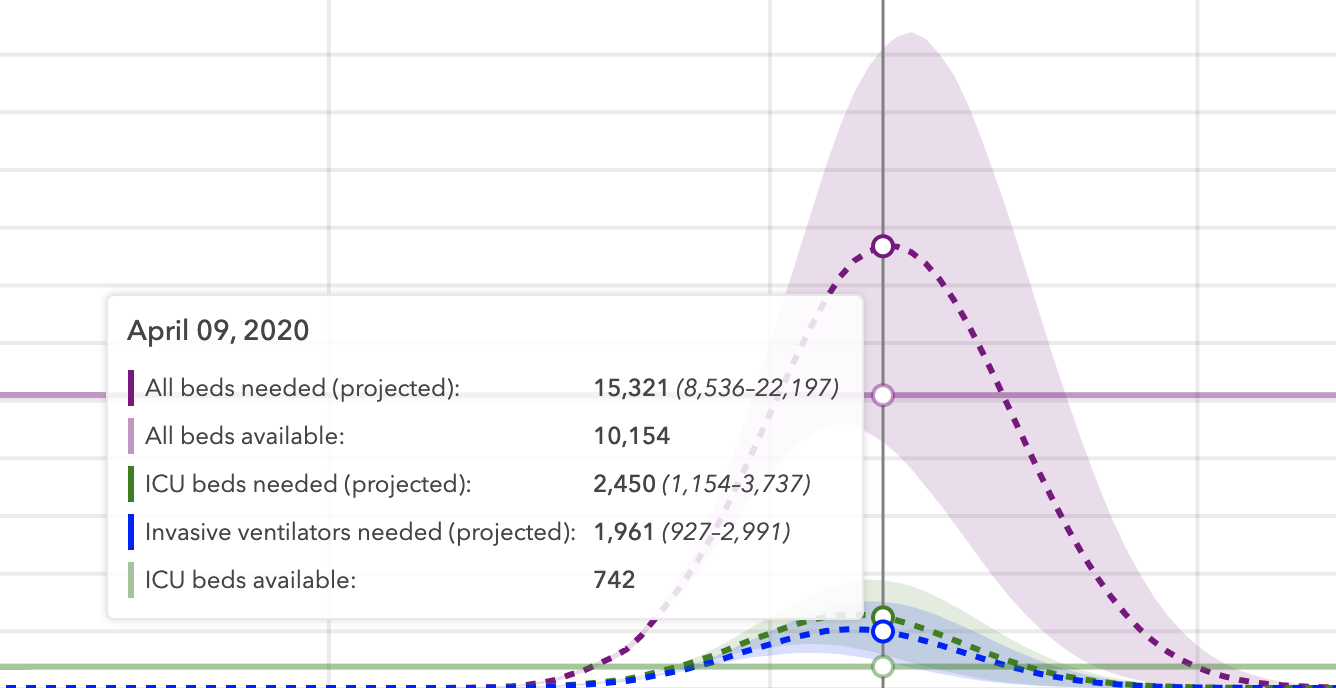

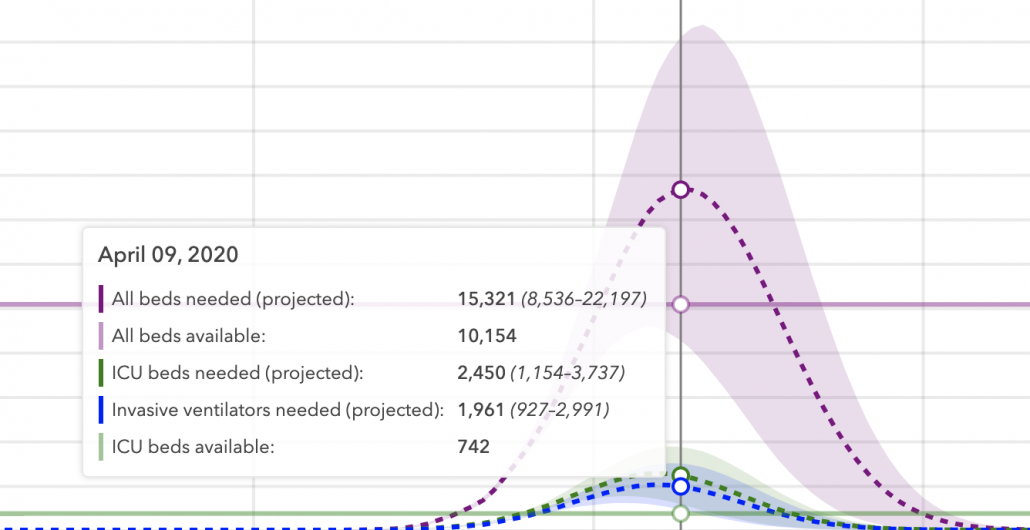

At present, based on the information available, the rate of growth of deaths from COVID-19 in Michigan is at least as fast as New York, if not faster. The modeling for our area shows that, at its current rate, we would exceed demand for hospital and intensive care services in early May and this would last many, many weeks. This peak in cases would be more than our health care system, or any health care system, could handle.

That conflicts with the IHME projection for the state by several weeks.

I thought, at first, that that might just reflect the fact that cases in my county, Kent County, have been increasing at a more gradual pace than in SE MI. That is, it might reflect that our curve is flatter than the state as a whole, and while Kent is the state’s fourth biggest county, the population of those hardest hit county still dwarfs ours.

Except that Governor Whitmer has twice used the same estimate for our curve — early May. In both a press conference yesterday and in a town hall, she and MI’s Chief Medical Executive Joneigh Khaldun said our peak will be a month from now, not a week.

Maybe Whitmer and Spectrum and everyone else are trying to prepare for the worst. Or maybe they’re seeing something in the state-level data that is not making it into the public data IHME is using.

A physician leader at a major academic medical school in the south walked me through some of what the IHME model may not fully incorporate, based on what he’s seeing in a hard-hit city: how long patients are kept on ventilators.

As you know I am exec leadership at a large University Hospital, so I have access to our Covid data.

I suspect one of the factors driving the later projected peaks is related to estimates of time in hospital. While some non-critical patients are admitted and discharged over 3-7 days, the ones admitted to the ICU are taking much longer to move.

The peak of detecting infection precedes the peak need for hospitalization by 7-10 days.

If you look at the IMHE data, their curves for hospitalization and need for ICU and ventilators are temporally aligned. I think this is going to be very wrong.

The issue is that once a patient is in the ICU or on a ventilator, they stay for a very long time, remaining on the ventilator. Since mid-March, we have intubated numerous patients. 10% have been extubated, 20% have died, and 70% remain intubated and are still parked in the ICU.

Thus the peak need for ICU/Ventilator curve should probably be pushed back several weeks as the tail end of the infections will just accumulate more ICU/vent need in the weeks subsequent to the infection/hospitalization peaks. I suspect the local governments are figuring this out, and the math guys at IMHE have not plugged this factor into their models yet.

The burden on health care capacity will persist long after the infections abate- necessitating much longer control measures to avoid and reemergence in volume.

If this is right, then it may reflect differing goals. Whitmer and Spectrum Health need to identify how many ventilators they’ll need for how long, whereas the federal government needs to identify how long it’ll take to get the first wave of people who’ve contracted the virus either into hospitals or through the period of contagion. Though if that’s right, it may explain why Jared Kushner and others at the White House think governors are exaggerating the number of ventilators they need: because Kushner isn’t accounting for how long a patient stays on a ventilator.

But if Michigan is right and IHME is wrong, it matters that the White House has largely endorsed the IHME model. Even ignoring the possibility that IHME is not sufficiently accounting for the time patients spend on ventilators, there are parts of the projections that do not match reality. The IHME model assumes every state will have a stay-at-home order, but a bunch still don’t and the White House recommendations still fall far short of that. The IHME model assumes everyone will remain on stay-at-home until June (an assumption it made far more prominent on its site after the White House endorsed the model), but Trump promised it would be just 30 more days. While IHME uses deaths to project the curve — justifiably treating that as a more reliable measure of COVID rates than tested positives — there’s reason to believe that even death rates are unreliable (for example, some areas are showing spiking pneumonia deaths not otherwise attributed to COVID-19).

As it is, Trump promised that everything would start to get better in two weeks (though later in his presser, he admitted it might be three weeks). He did so while falsely suggesting that the IHME projections match the recommendations of his White House, which they don’t.

But if hard-hit states like NY (for which IHME has already significantly adjusted its model) and MI are as much as a month out from peak, then Trump’s rosy projections could, once again, lead to recklessness.