Seth DuCharme’s Information Operation

Former Bill Barr aide Seth DuCharme did something funny in his two sentencing memos for former FBI counterintelligence professional Charles McGonigal.

Secret meetings

In his SDNY sentencing memo, he redacted a long paragraph which, by context, purported to describe cooperation.

SDNY was having none of that.

They explained that the redacted passage described a single meeting he had in which he shared — per a participant — “insignificant” information, not anything that merited a bonus for cooperation.

McGonigal describes an interview with other government agencies, at which he answered questions about misconduct others may have committed and his own conduct. (Br. 15- 16). The U.S. Attorney’s Office conducting this prosecution did not request that meeting, did not attend that meeting, and has little knowledge of what was said there, beyond a brief summary from one of its participants—who characterized the contents of McGonigal’s statements as, in substance, insignificant. There thus appears to be no basis for McGonigal to “presume” that his statements were “of some assistance.” (Br. 16).11 Nor can McGonigal seek sentencing credit for this meeting by citing United States v. Fernandez, 443 F.3d 19, 33 (2d Cir. 2006), abrogated by Rita v. United States, 551 U.S. 338 (2007). As McGonigal notes, that case states that a sentencing court could consider a defendant’s efforts to cooperate with the Government even if those efforts did not result in a cooperation agreement. (Br. 16). But its holding was that the district court was within its discretion to conclude “that the cooperation was fitful and that it should not be used to lighten [the defendant’s] sentence.” Fernandez, 443 F.3d at 34 (internal quotation marks omitted). This Court should reach the same conclusion with respect to McGonigal’s attempt to obtain a lenient sentence by attending a single meeting.

In a footnote, they tattled on DuCharme for trying to inflate the value of it by unilaterally redacting it.

11 The Court should not infer from McGonigal’s sealing of the corresponding paragraph in his submission that he has provided information of any value. The Government did not ask that this paragraph be sealed. Rather, McGonigal’s attorney informed the undersigned and the Washington, D.C. prosecutors that he intended to seal the paragraph, and neither objected.

DuCharme didn’t even attempt this ploy in DC. This time he left the paragraph unsealed.

When the United States presented him with a reasonable plea offer during the discovery phase of this case, Mr. McGonigal swiftly agreed to accept responsibility for his actions. In addition, he agreed to meet with representatives from seven different DOJ offices after his plea and provided truthful information to the government during a seven-hour interview session.

[snip]

Moreover, after Mr. McGonigal entered his plea, on November 17, 2023, at the request of the United States, Mr. McGonigal met with seven components28 of the Justice Department simultaneously in Manassas, Virginia, where he answered all questions presented to him on a wide variety of topics, including detailed discussions of his understanding of certain events, and his considered assessment of what the FBI can do to improve its compliance policies and practices to detect and deter improper conduct within the organization. We have been informed that the United States found the information that Mr. McGonigal provided during the full-day interview to be truthful and, we presume, of some assistance given the length and detail of the discussions.

Though by feigning coy about which parts of DOJ he met with, he again tried to fluff the import of it.

28 The specific components represented are not listed here, out of respect for sensitivities related to their specific areas of responsibility, but that information is available upon request if it is material to Court’s consideration.

DC USAO, which must have set up the meeting, didn’t mention it. Instead, they described the extensive effort FBI has made to make sure McGonigal didn’t drum up investigations into other people to help friends overseas, as he seems to have done for Albania.

Moreover, given the defendant’s senior and sensitive role in the organization, the FBI has been forced to undertake substantial reviews of numerous other investigations to insure that none were compromised during the defendant’s tenure as an FBI special agent and supervisory special agent. The defendant worked on some of the most sensitive and significant matters handled by the FBI. PSR ¶¶ 98-101. His lack of credibility, as revealed by his conduct underlying his offense of conviction, could jeopardize them all. The resulting internal review has been a large undertaking, requiring an unnecessary expenditure of substantial governmental resources.

This may be the only passage, in either DOJ sentencing memo, that discussed what a lasting harm having a top spymaster team up with foreigners seeking favors is for the FBI.

It suggests that DOJ might trust McGonigal to discuss “compliance policies,” but no longer the counterintelligence investigations in which he played a role.

Non-spy charges against the spy chief

I thought DuCharme’s ploy to provide the appearance of cooperation via evasion and redaction made an amusing introduction to something else I’ve been meaning to write, as part of my Ball of Thread series.

There was some consternation when McGonigal got sentenced in December to (just) 50 months for working for Oleg Deripaska. The complaint was, I think, that McGonigal hadn’t been labeled a spy, with some belief that would have changed the outcome.

I’d like to explain why, I suspect, DOJ did what they did.

I think they got a similar outcome as they would have had they called what he did “spying,” but deprived McGonigal — and just as importantly, DuCharme, who tried to pitch the “insignificant” information he shared as some great cooperation — from conducting an information operation to undercut the prosecution.

McGonigal was prosecuted for two schemes.

In DC, he was charged for secretly getting paid by, and traveling with, top Albanians, and ultimately predicating a FARA investigation into a Republican lobbyist with ties to a rival Albanian faction. For that, McGonigal was charged with a bunch of disclosure violations, making the secrecy the crime, not the scheming with Albania. The government is asking Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly to sentence him on February 16 to 30 months; they have not explicitly asked her to impose the sentence consecutively, which is the only way this sentence would extend his detention.

In NY, he was charged for secretly working with Oleg Deripaska. For that, he was charged with sanctions violations and money laundering. After he pled to conspiracy, the government had asked Judge Jennifer Rearden to sentence him to the max 60 months; she gave him the aforementioned 50 month sentence.

The government has not claimed to have proof that McGonigal shared any sensitive information with Deripaska or the Albanians, whether they have it and aren’t telling, or whether there is none. Without it, you would not expand McGonigal’s potential sentence by charging him with the crimes that might label him a spy: Foreign Agent crimes in DC, since he was working for a foreign state, or FARA in NY, since Deripaska is not quite the same thing as the Russian state. By larding on the disclosure violations in DC and asking for an obstruction enhancement, DOJ has raised total possible exposure there. And no FARA charges would carry a tougher sentence than the potential 20 year money laundering sentence that McGonigal avoided by pleading out in SDNY.

That is, DOJ charged McGonigal in such a way that the punishment would be the same, the 20 years on the money laundering charge or five-plus on disclosure violations, without giving McGonigal a cause to demand information exposing his operations at FBI.

But he did try.

Deripaska’s visit

Before I explain how, let’s situate things a bit.

According to Business Insider, a tip from the UK is one of the things that led to the investigation into McGonigal. They picked him up via the surveillance of a Russian in London they were tracking.

In 2018, Charles McGonigal, the FBI’s former New York spy chief, traveled to London where he met with a Russian contact who was under surveillance by British authorities, two US intelligence sources told Insider.

The British were alarmed enough by the meeting to alert the FBI’s legal attaché, who was stationed at the US Embassy. The FBI then used the surreptitious meeting as part of their basis to open an investigation into McGonigal, one of the two sources said.

Whether the UK picked him up in 2018 or 2019, according to the indictment his meetings with Deripaska — including in London — were in 2019.

In or about 2019, after McGONIGAL had retired from the FBI, SHESTAKOV and McGONIGAL introduced [Evgeny Fokin] to an international law firm [Kobre & Kim] with an office in Manhattan, New York (the “Law Firm”). [Fokin] sought to retain the Law Firm to work in having the OFAC Sanctions against Deripaska removed, a process often referred to as “delisting.”

During negotiations to retain the Law Firm, McGONIGAL traveled to meet Deripaska and others at Deripaska’s residence in London, and in Vienna. In electronic communications exchanged as part of these negotiations, McGONIGAL, SHESTAKOV, [Fokin] and others did not refer to Deripaska by his surname, but rather used labels such as “the individual,” “our friend from Vienna,” and “the Vienna client.”

DuCharme asserted at McGonigal’s SDNY sentencing that working with a law firm on delisting Deripaska in 2019, “would have been legal.”

After Charlie left the FBI, he met Oleg Deripaska. He met him in London in a prestigious international law firm with a lawyer. But I think the government agrees that that part would have been legal, because there is the carve-out for certain legal representations.

That didn’t go through.

It’s true that there’s a carve out for legal services that would make that, in general, legal. Probably far less so if you know that the guy you’re working with is a Russian spy.

DuCharme claims McGonigal did not, at least with regards to Fokin.

So this person, Fokin, reaches out to Charlie after that at some point. And just to be clear, as far as Mr. McGonigal knows, Fokin is not, as I guess is rumored in the media, to be a Russian intelligence officer. That’s not his understanding. But he certainly knows him to be associated with Oleg Deripaska; and he certainly knows that Deripaska is on the sanctions list.

The indictment and government sentencing memo, however, describe that McGonigal told a subordinate that Fokin was a spy.

McGonigal also told a subordinate that he wanted to recruit Fokin, who was, according to McGonigal, a Russian intelligence officer.

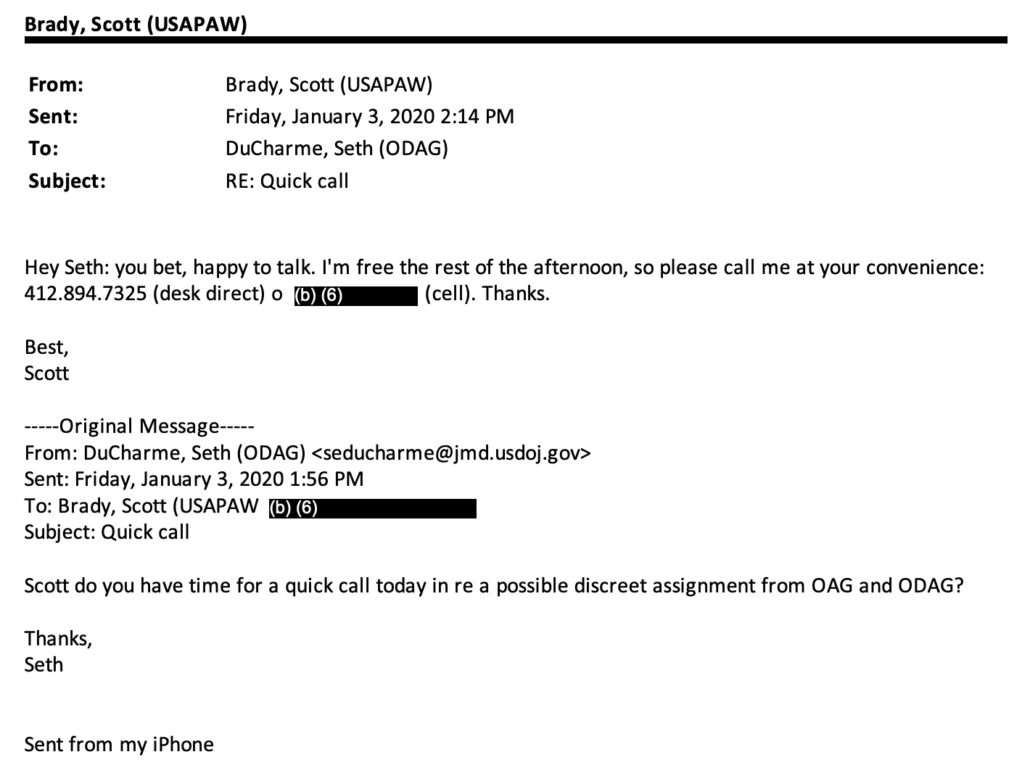

Let’s situate where things were in 2019. McGonigal was, without question, retired from the FBI. But at the time, DuCharme was working for Bill Barr, among other things, setting up an investigation to undermine the Russian investigation that disclosed how a close Deripaska associate, Konstantin Kilimnik, used Paul Manafort’s debt to Deripaska as leverage to learn how Trump planned to beat Hillary Clinton and also discuss carving up Ukraine to Russia’s liking. DuCharme would go on from there to set up a back channel via which Rudy Giuliani could channel dirt, including from a known Russian spy, into the Hunter Biden investigation.

A meeting with a law firm would have been legal. And also, DuCharme and his boss were working hard to blame the 2016 Russian operation on Hillary rather than Deripaska, recklessly chasing leads to those involved all over the world.

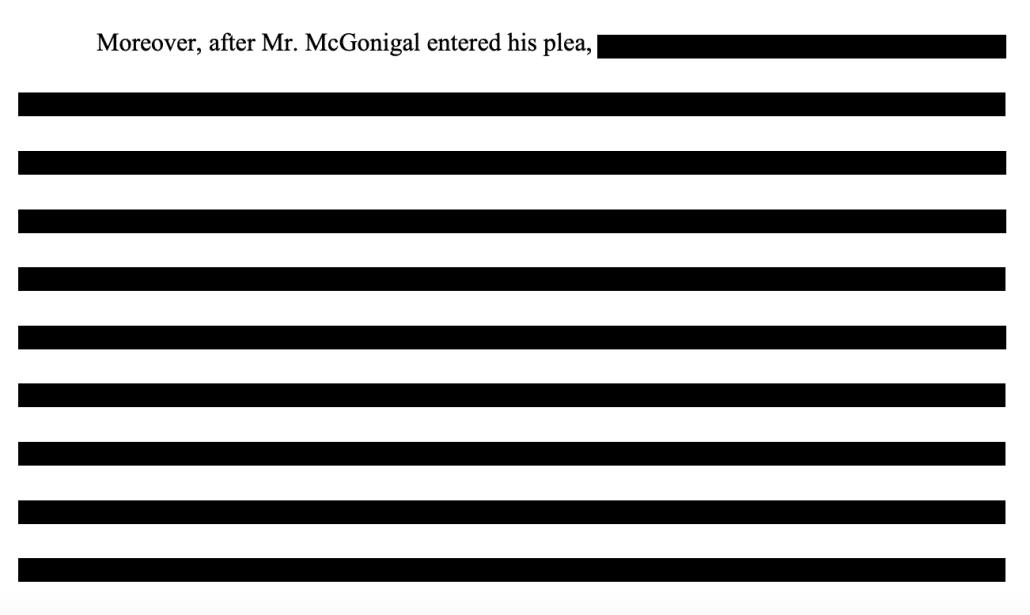

In fact, among the leads that DuCharme was chasing in 2019 as he and John Durham (he of the studied ignorance about what really happened) dreamt up ways to undermine results showing Trump welcomed help from Russia — along with the Russian-backed Ukrainians and Joseph Mifsud — involved Deripaska.

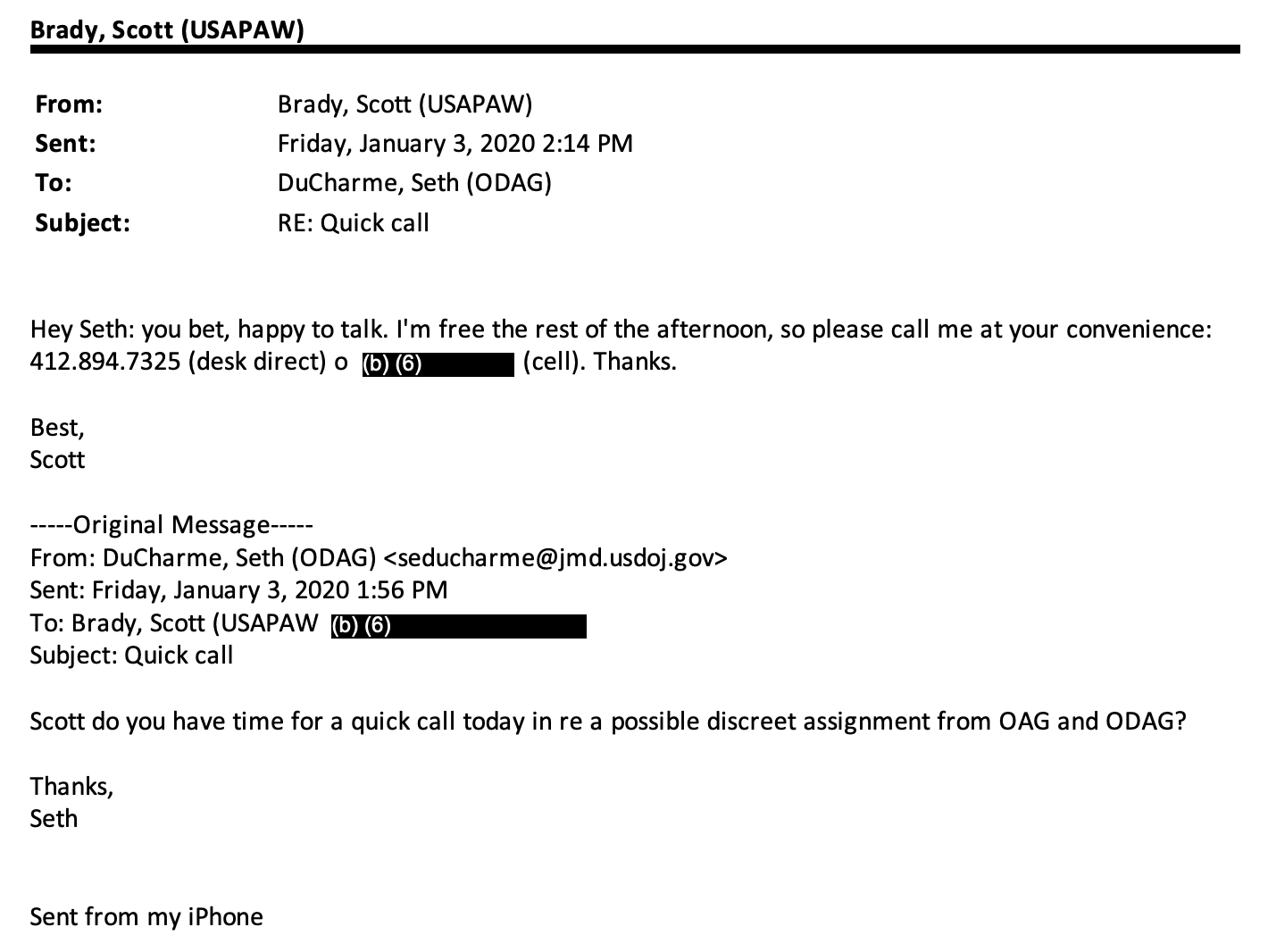

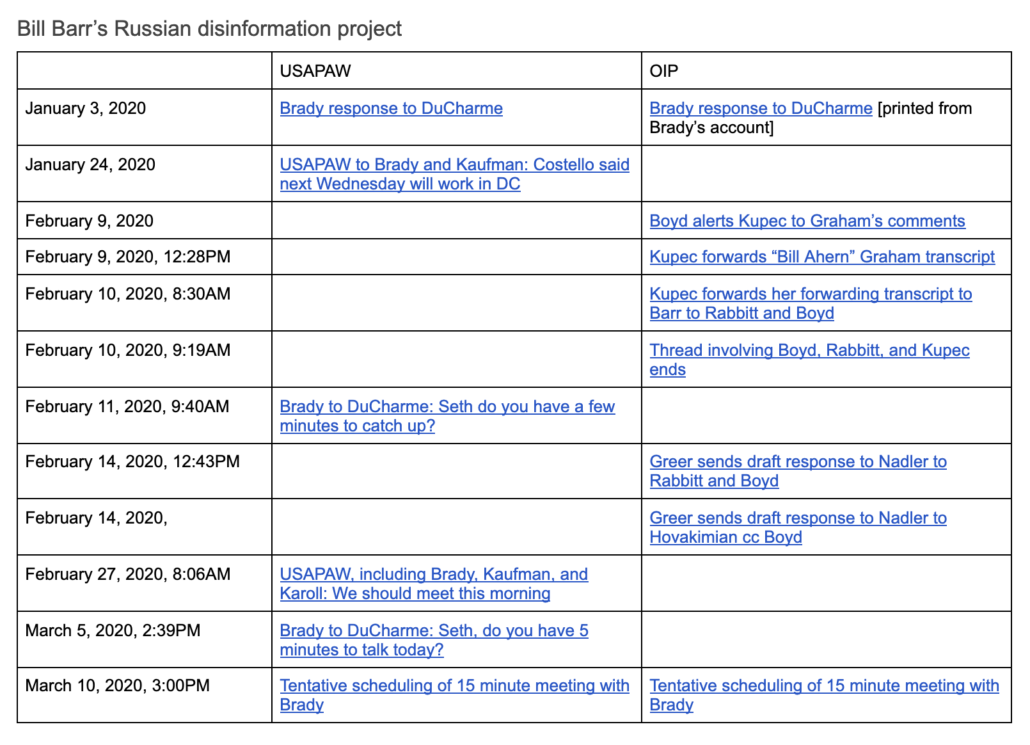

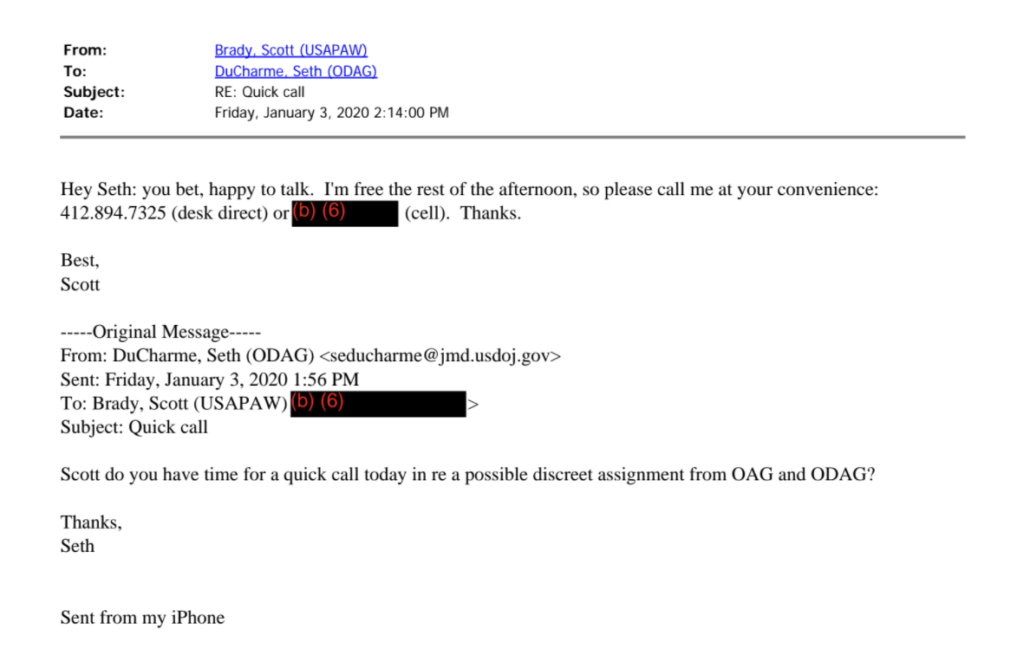

On July 3, 2019, DuCharme emailed Durham about a Fox News report that FBI had worked with Oleg Deripaska in an attempt to get Robert Levinson released and returned by Iran.

To be sure, unlike Mifsud and the Ukrainians, there’s no record DuCharme and Durham and Barr did chase the possibility that Deripaska would have damning information on Andy McCabe.

Though two months before DuCharme sent Durham a lead on Deripaska, on May 1, 2019, Bill Barr’s face melted when Ben Sasse asserted that Deripaska was a “bottom-feeding scum-sucker.”

Anyway, back to McGonigal and his charges for secretly working for Deripaska.

The investigation into McGonigal went overt in November 2021 and after that point, DuCharme described, McGonigal’s counsel, presumably DuCharme himself, remained in contact with the government.

More than a year before his arrest, on November 21, 2021, FBI agents conducted a recorded, voluntary interview of Mr. McGonigal at Newark airport when he returned home from an overseas business trip. While he was speaking to agents at the airport, another team of agents visited Mr. McGonigal’s home in lower Manhattan and met with his wife. Over the following year, Mr. McGonigal was aware of the ongoing investigation into his business dealings and remained in communication with the United States through his counsel.

So as SDNY and DC USAO were contemplating how to charge their former spymaster leading up to his January 2023 indictments, they knew that they would have to contend not just with McGonigal’s former Top Secret clearance, but also that of his attorney, the guy who in at least two cases facilitated the intake of spy dirt for partisan purposes on behalf of the former Attorney General.

Graymail

DuCharme was well aware of that.

In his DC sentencing memo, for example, he described how, by pleading guilty relatively quickly, McGonigal saved the government from engaging in the Classified Information Procedures Act process, the process by which the judge acts as an intermediary to make sure that defendants can get classified information that would be helpful to a defense without unnecessarily compromising information that would be of no help.

In contrast to Mr. Saffarinia, Mr. McGonigal quickly accepted responsibility for a single count of false statements through his guilty plea, avoiding any further expenditure of government resources, including potential Classified Information Procedures Act (“CIPA”) litigation.

It’s not true, however, that McGonigal spared SDNY of using the CIPA process. Though something very funky happened in that process in SDNY, which I believe is a big testament to the reason why they treated McGonigal’s exposure there the way they did, by charging him with crimes that would carry the same punishment without charging with a foreign agent crime. I first wrote about this funkiness here.

It seems like SDNY pre-empted a full-blown CIPA practice by having select documents, dating to well before McGonigal got into discussions with Deripaska’s people, that made clear that Deripaska was, “associated with a Russian intelligence agency” that must be GRU, which meant nothing that happened downstream of that knowledge would be all that helpful to McGonigal’s defense. That is, DuCharme may claim, evidence to the contrary, that McGonigal didn’t believe Fokin is a spy, but SDNY declassified a very small subset of documents making it clear McGonigal had to have known Deripaska was associated with GRU.

That’s part of the story that would have been told had this gone to trial: that when McGonigal secretly went to work for Deripaska, he knew of his ties to Russian intelligence.

SDNY must have planned this from the start.

It started on February 8, 2023, shortly after his indictment, when SDNY filed a CIPA letter, requesting a CIPA 2 conference.

Often, these CIPA letters review the entire CIPA process. The one Jay Bratt submitted in the Trump stolen documents case, for example, went through Section 1, Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 (broken down by sub-section), Section 7, Section 8, Section 9, and Section 10.

Not the SDNY one in the McGonigal case. It went through Section 2 — asking for a conference — and then stopped.

The Government expects to provide the Court with further information about whether there will be any need for CIPA practice in this case, and to answer any questions the Court may have, at the CIPA Section 2 conference.

In response, on March 1, DuCharme submitted his own CIPA letter, laying out Sections 1 through 8. Along the way, DuCharme promised that as part of CIPA 4, he would submit a memo telling Judge Jennifer Rearden what kind of information would be helpful to Charlie McGonigal’s defense, much later describing surveillance that must exist.

Under Section 4, upon a “sufficient showing” by the government, the Court may authorize the government to “delete specified items of classified information from documents to be made available to the defendant . . . , to substitute a summary of the information for such classified documents, or to substitute a statement admitting relevant facts that the classified information would tend to prove.” 18 U.S.C. § App. III § 4. The government makes a sufficient showing that such alternatives are warranted through an ex parte submission to the Court. See id; see also United States v. Muhanad Mahmoud Al-Farekh, 956 F.3d 99, 109 (2d Cir. 2020). Of critical importance to the fairness of the process, the Court may review, ex parte and in camera, the classified information at issue to determine whether and in what form the information must be disclosed to the defendant, and whether the government has truly satisfied its discovery obligations. See, e.g., United States v. Aref, No. 04 CR 402, 2006 WL 1877142, at *1 (N.D.N.Y. July 6, 2006). To assist the Court in this analysis, the defense will provide the Court with its initial view of the scope of material that will be relevant and helpful in the preparation of the defense at the upcoming conference and will supplement that information as appropriate.

[snip]

In the present case, there is far more than a trivial prospect, and in fact there is a high likelihood if not certainty, that the IC possesses information that is relevant and helpful to the preparation of the defense. The indictment charges violations of IEEPA based on an alleged agreement to provide services on behalf of Oleg Deripaska, a foreign national with allegedly close ties to a foreign government, who, it is reasonable to assume, may have been a target of surveillance by the United States during the relevant time frame. Moreover, the indictment makes specific references to previously-classified information that was in the possession of the IC, to which Mr. McGonigal had access by virtue of his position as Special Agent in Charge of the Counterintelligence Division of the New York Field Office. [my emphasis]

Seth DuCharme set out to know, among other things, what kind of surveillance FBI obtained on McGonigal, including whatever surveillance the Brits picked up when they first grew concerned about McGonigal meeting certain Russians in London.

Things never got to CIPA 4.

On March 3, Judge Rearden confirmed she would hold two separate CIPA conferences. The SDNY conference was held on March 6. On March 7, the day after SDNY’s CIPA conference and the day before McGonigal’s, SDNY responded to McGonigal’s CIPA letter. It suggested that any investigation the Intelligence Community did of McGonigal’s “corruption” by Deripaska would not be helpful to his defense. But if McGonigal wanted to make a list of things he specifically wanted, he should put that in writing.

McGonigal’s letter repeatedly asserts that the intelligence community must possess information that is helpful to his defense, without specifying what that information must be or what agencies must possess it. (See, e.g.¸ Dkt. 30 at 6 (claiming that the intelligence community writ large “may be presumed to have been involved” in the investigation of this matter); id. at 7 (asserting that “in fact there is a high likelihood if not certainty, that the IC possesses information that is relevant and helpful to the defense”)). At best, he has suggested that the general subject of this case—a recently retired FBI intelligence official being corrupted by a Russian oligarch—is of the type that might be of interest to intelligence agencies.2 Even if that claim is true, however, it is a far cry from suggesting that those agencies possess anything helpful to the defense.

[snip]

Finally, McGonigal suggests that he will “identify categories of classified information that will be material to his defense at the defendant’s ex parte Section 2 conference.” (Dkt. 30 at 7). But it is unclear why he needs to do this in an ex parte conference. As he elsewhere acknowledges, CIPA establishes procedures for the defense to identify classified information it wishes to offer, and those procedures are not ex parte.

[snip]

The Government thus trusts that McGonigal will identify any classified information he claims is relevant to the Government, as CIPA elsewhere expressly provides. See id. § 5 (“If a defendant reasonably expects to disclose or to cause the disclosure of classified information in any manner in connection with any trial or pretrial proceeding involving the criminal prosecution of such defendant, the defendant shall, within the time specified by the court or, where no time is specified, within thirty days prior to trial, notify the attorney for the United States and the court in writing.” (emphasis added)).3

On May 8, SDNY filed a short letter informing Judge Rearden that they had declassified the material they had told her they would in their own CIPA 2 hearing and provided it to the defense.

At the March 6, 2023 ex parte conference held pursuant to Section 2 of the Classified Information Procedures Act (“CIPA”) in the above-referenced case, the Government described to the Court certain materials that the Government was seeking to declassify. The Government writes to confirm that those materials have been declassified and produced to the defendants. At this time, the Government does not anticipate making a filing pursuant to Section 4 of CIPA and believes it has met its discovery obligations with respect to classified information.

It seems likely that this declassified material includes the document, which McGonigal received in May 2017, identifying Deripaska’s ties to (what must be) GRU disclosed in the government’s sentencing memorandum. Effectively, SDNY was saying that, once you understand Deripaska was GRU (and whatever else also got declassified), anything that came after that would not be helpful to your defense.

DuCharme was not yet done. On June 23, he submitted another letter describing that it was perplexing and puzzling and concerning and hard to imagine that there wasn’t more.

With respect to the way forward as it pertains to classified discovery, as we noted at our last court appearance, the government has indicated that it “does not anticipate making a filing pursuant to Section 4 of CIPA and believes it has met its discovery obligations with respect to classified information.” See ECF No. 44 at 1. In a subsequent series of conversations, the government informed us, in a general way, that it has satisfied its discovery obligations relating to classified information. The government’s position is perplexing. While it is not surprising that the government does not wish to account for its each and every step in satisfying its constitutional obligations, it is puzzling and concerning that the government would, at this stage, determine that no CIPA Section 4 presentation to the Court is appropriate, when we are a year away from trial and the government’s discovery obligations with respect to Rule 16, the Jencks Act, Brady and Giglio are ongoing. The indictment and the U.S. Attorney’s press release include accusations that foreseeably implicate classified information within each of the four categories of discoverable information. With respect to the category of impeachment material alone, it is hard to imagine a world in which there are no classified materials that touch on the credibility of the government’s trial witnesses (or alleged unindicted coconspirator hearsay declarants), and which would require treatment under Section 4 of CIPA.

DuCharme suggested that maybe the problem was that the information helpful to McGonigal’s defense was simply super duper classified, but that it still had to be turned over.

As an initial matter, the classification level of information in the possession of the United States is wholly irrelevant as to whether or not it is discoverable. Classification rules appropriately exist to safeguard the national defense of the United States by limiting the dissemination of such information in the normal course. See Exec. Order No. 13526, 75 Fed. Reg. 707, (2009) (prescribing a uniformed system for classifying national security information). But once a defendant is indicted, the government is obligated to consider whether information within its holdings is discoverable under the applicable rules, statutes and constitutional caselaw

The letter explained that both McGonigal and Seth DuCharme could be trusted with the government’s classified information — after all, McGonigal was only indicted for cozying up to the Russian oligarch he had hunted for years, not mishandling classified information. And Seth DuCharme was, until recently, trusted with Bill Barr’s most sensitive secrets, including about the side channels ingesting dirt from known Russian agents.

Further, it is hard to understand why the government is so reluctant to be more transparent in explaining its discovery practices to the defense in this case. While many national security cases involve defendants with no prior clearances or experience with the U.S. Intelligence Community, and may involve only recently-cleared defense counsel who may be new to navigating the burdens and responsibilities of handling classified information, here, those concerns do not apply. Mr. McGonigal was one of the most senior and experienced national security investigators in the FBI with significant direct professional experience in the areas germane to his requests for assurances about the thoroughness of the government’s discovery analysis. In addition, before moving to private practice, the undersigned counsel served as the Chief of the National Security Section, the Chief of the Criminal Division and the Acting United States Attorney in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Eastern District of New York as well as the Senior Counselor to the Attorney General of the United States for National Security and Criminal matters, and has responsibly held TS/SCI clearances with respect to some of the United States government’s most sensitive programs. As the Department of Justice has concluded in re-instating defense counsel’s clearances for the purpose of this case, we are trustworthy. So, here, we have a defendant and defense counsel who are highly respectful and experienced with regard to the protocols for handling and compartmentalizing sensitive classified information, and simply request comfort that the government has indeed done everything it would normally do in a case such as this, with sufficient detail to assess the credibility of the government’s position.

Notably, Mr. McGonigal has not been accused of mishandling classified information in the cases brought against him, and he maintains respect for the national security interests of the United States, as of course do we. In addition, we are not asking the government to disclose to the defense any sensitive sources and methods by which discoverable information was collected—only to provide greater transparency to us, and to the Court, as to how it views its procedural obligations, so that we may consider the fairness and reasonableness of the government’s approach. Mr. McGonigal is personally familiar with this process from his time at the FBI, and it is reasonable for him to expect to be treated no worse than the other defendants who have come before him. To adequately represent Mr. McGonigal, it seems only fair that we be allowed to hold the United States government to the same standards that the defendant upheld as a national security and law enforcement professional, and to make a record of the government’s position.

Then DuCharme made a helpful offer to meet in a secure hearing or to submit a more highly classified brief — perhaps taking SDNY up on their instruction to put it in writing — again suggesting he had something specific in mind.

In sum, if the government could explain, in an appropriate setting, how it determined that it had obviated the need for a CIPA Section 4 proceeding, we likely can avoid speculative motion practice, and the parties and this Court may be assured that we can continue to litigate this case fairly and with the level of confidence to which we are entitled.

[snip]

To the extent the Court would like more detailed briefing on these issues prior to the conference, the CISO has provided to cleared defense counsel access to facilities that would allow us to draft a supplemental submission at a higher classification level.

I don’t want to minimize the problem CIPA presents for defendants, nor the kind of prosecutorial dickishness that can roil discovery discussions. But this entire exchange was, in my experience, pretty remarkable. The arguments, for example, are little different from ones Trump is making in the stolen documents case, but McGonigal’s arguments always seemed more targeted than Trump’s, which are a mad splay attempting to review the entire Intelligence Community.

Then it was over.

On June 23, DuCharme doubled down on his certainty there were secrets that would help McGonigal. On July 10, Judge Rearden scheduled a hearing for updates on classified discovery. That same day, the government described making a discovery production four days after DuCharme’s letter, then said it planned to file a response to the letter before the hearing, which it said was scheduled for July 18. Judge Rearden gave them four days to file the response, until July 14. That day, July 14, the day SDNY would otherwise have filed another public letter about classified discovery, McGonigal withdrew his request for a status hearing. A month later McGonigal pled guilty to the one count of conspiracy.

To be sure, the deal was pretty sweet, given that it took the onerous money laundering exposure off the table. But the 50 months is the kind of sentence he might have faced for Foreign Agent charges — anything that stopped short of alleging that McGonigal had shared FBI secrets with Oleg Deripaska, of which, again, there is no hint in any of the charging documents.

Yet SDNY successfully prosecuted the former FBI spymaster for working for Oleg Deripaska without (apparently) sharing anything more than the first notices McGonigal got of the spook ties the Intelligence Community found Oleg Deripaska to have.