Former NSA Counsel Stewart Baker has been in an increasingly urgent froth since Edward Snowden’s leaks first became public trying to prove that the NSA should have more, not less, unchecked authority.

He outdid himself yesterday with an attempt to respond to Jack Goldsmith’s question,

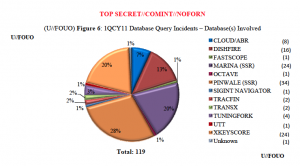

How is the NSA Director Alexander’s claim that “we can audit the actions of our people 100%” (thus providing an important check against abuse) consistent with (a) stories long after Snowden’s initial revelations that the White House does not “know with certainty” what information Snowden pilfered, (b) reported NSA uncertainty weeks after the initial disclosure about what Snowden stole, (c) Alexander’s own assertion (in June) that NSA was “now putting in place actions that would give us the ability to track our system administrators”?

Baker’s totally inadequate response consists of pointing to certain features of XKeyscore revealed by the Guardian.

Take a close look at slide 7 of the latest leaked powerpoints.

It shows a sample search for a particular email address, including a box for “justification.” The sample justification (“ct target in n africa”) provides both the foreign intelligence reason for surveillance and the location of the target. What’s more, the system routinely calls for “additional justification.” All this tends to confirm NSA’s testimony that database searches must be justified and are subject to audits to prevent privacy abuses.

Now, I don’t know about Baker, but even without a drop-down menu, the average American high schooler is thoroughly adept at substituting a valid justification (“grandmother’s funeral,” “one day flu”) for an invalid one (“surfs up!” “first day of fishing season”). I assume the analysts employed by NSA are at least as adept at feeding those in authority the answers they expect. XKeyscore just makes that easier by providing the acceptable justifications in a drop-down menu.

More problematic for Baker, he commits the same error the Guardian’s critics accuse it of committing: confusing a User Interface like XKeyscore or PRISM with the underlying collections they access. (The Guardian has repeated Snowden and Bill Binney’s claims the NSA collects everything, without yet presenting proof that that includes US person content aside from incidental content collected on legitimate targets.)

That error, for Baker, makes his response to Goldsmith totally inapt to his task at hand, answering Goldsmith’s questions about what systems administrators could do, because he responds by looking at what analysts could do. Goldsmith’s entire point is that the NSA had insufficient visibility into what people with Snowden’s access could do, access which goes far beyond what an analyst can do with her drop-down menu.

And one of the few documents the government has released actually shows why that is so important.

The Primary Order for the Section 215 metadata dragnet, released last week, reveals that technical personnel have access to the data before it gets to the analyst stage.

Appropriately trained and authorized technical personnel may access the BR metadata to perform those processes needed to make it usable for intelligence analysis. Technical personnel may query the BR metadata using selection terms4 that have not been RAS-approved (described below) for those purposes described above, and may share the results of those queries with other authorized personnel responsible for these purposes, but the results of any such queries will not be used for intelligence analysis purposes. An authorized technician may access the BR metadata to ascertain those identifers that may be high volume identifiers. The technician may share the results of any such access, i.e., the identifers and the fact that they are high volume identifers, with authorized personnel (including those responsible for the indentification and defeat of high volume and other unwanted BR metadata from any of NSA’s various metadata respositories), but may not share any other information from the results of that access for intelligence analysis purposes. In addition, authorized technical personnel may access the BR metadata for purposes of obtaining foreign intelligence information pursuant to the requirements of subparagraph (3)(C) below.

[snip]

Whenever the BR metadata is accessed for foreign intelligence analysis purposes or using foreign intelligence analysis query tools, an auditable record of the activity shall be generated.

Note, footnote 4 describing these selection terms is redacted and the section in (3)(C) pertaining to these technical personnel appears to be too.

Now, I suspect the technical personnel who access the metadata dragnet are different technical personnel than the Snowdens of the world. They’re data crunchers, not network administrators. Which only shows there’s probably a second category of person that may escape the checks in this system.

That’s because with their front-end manipulation of the dataset (though not the activities described under (3)(C)), these personnel are not conducting what are considered foreign intelligence searches of the database. The data they extract from the database is specifically prohibited (though, with weak language) from circulation as foreign intelligence information. That appears to mean their actions are not auditable. When Keith Alexander says the data is 100% auditable? You shouldn’t believe him, because his own document appears to say only the analytical side of this is audited. (The document also makes it clear that once the data has been queried, the results are openly accessible without any audit function; the ACLU had a good post on this troubling revelation.)

I suspect a lot of what these technical personnel are doing is stripping numbers — probably things like telemarketer numbers — that would otherwise distort the contact chaining. Unless terrorists’ American friends put themselves on the Do Not Call List, then telemarketers might connect them to every other American not on the list, thereby suggesting a bunch of harassed grannies in Dubuque are 2 degrees from Osama bin Laden.

But there’s also the reference to “other unwanted BR metadata.” As I’ll explain in a future post, I suspect that may be some of the most sensitive call records in the dataset.

Whatever call records get purged on the front end, though, it appears to all happen outside the audit chain that Keith Alexander likes to boast about. Which would put it well outside the world of drop-down menus that force analysts actions to conform with something that looks like foreign intelligence analysis.

In other words, even the document the government provided (with heavy redactions) to make us more comfortable about this program shows places where it probably has insufficient visibility on what happens to the data. And that’s well before you get into the ability of people who can override other technical checks on NSA behavior as system administrators.

Update: More froth from Stewart Baker. This response to my post seems to be an utter capitulation to Goldsmith’s point.

Wheeler thinks this is important because it means that the “justification” menus don’t guarantee auditability of every use of intercept data by every employee at NSA. Again, that may be true, but the important point about the “justification” menu isn’t that it offers universal protection against abuse; nothing does. [my emphasis]

Update: as Mindrayge notes, Marina appears in NSA slides as Internet, not phone metadata (and that’s how Ambinder refers to it here). There are some oddities, then, but I am changing this post accordingly.

Update: as Mindrayge notes, Marina appears in NSA slides as Internet, not phone metadata (and that’s how Ambinder refers to it here). There are some oddities, then, but I am changing this post accordingly.