Surveillance Whack-a-Mole, Section 215 to Section 702 Edition

As it happens, I and others covered the report that NSA purportedly has not restarted its use of the Section 215 CDR program in the wake of finding serious over-collection on the same day that I Con the Record released another Semiannual report on 702, the one completed in October 2018, which covers December 2016 to May 2017.

In my post on the Section 215 CDR claim, I suggested that function probably hasn’t shut down, but likely moved instead to a different authority, probably EO 12333.

The NSA almost never gives up a function they like. Instead, they make sure they don’t have any adverse court rulings telling them they’ve broken the law, and move the function some place else. Given that the government withdrew several applications last year after FISC threatened to appoint an amicus, and given that the government now has broadened 12333 sharing, they may have just moved something legally problematic somewhere else.

In Ellen Nakashima’s report on the 215 CDR shutdown, she suggested that NSA may not longer need the 215 CDR function because “terrorists” (this program was never just about terrorists) increasingly use secure apps which “don’t always create metadata.”

But these days, terrorists generally are not coordinating via phone calls or standard text messages, but communicate by using secure apps that don’t always create metadata trails, analysts said.

That is, the suggestion is that because “terrorists” are using encrypted apps like Signal and WhatsApp rather than AT&T or Verizon’s own SMS apps, getting the latter via the CDR program is not as useful.

But perhaps that explains the over-collection issue behind all this.

From the start of the USA Freedom Act debate, I have noted that the definition used in the law — session identifier — did not match the intent of most members of Congress: that is, to track telephony contacts. Telephony contacts are just an increasingly minimal subset of the session identifiers than any mobile phone user will generate. And in the age of super-cookies, providers increasingly track these other session identifiers. If providers collect it, spooks and law enforcement will try to use it, and the expanded universe of session identifiers is no exception.

One of several likely explanations for the over-collection that led the government to destroy all its records last year is that the FISA Court wrote something that distinguished between the two (basically, establishing a precedent that made fudging the issue legally problematic), leading NSA to “discover” the over-collection and quickly start deleting records before any overseer found the proof that it was no accident.

At least, that same pattern has happened numerous times before.

Anyway, back to surveillance whack-a-mole.

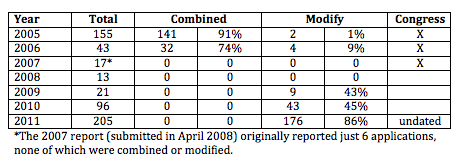

When this has happened in the past, the NSA didn’t actually shut down the function. It instead moved it to another authority, preferably one with less court oversight. Of particular note, when NSA shut down the PRTT dragnet in 2011, it moved some of that function to EO 12333 (NSA had resumed a practice shut down during the Stellar Wind shutdown allowing the agency to chain on Americans) and Section 702.

That’s why I want to point to something in the most recent Section 702 Semiannual Report (which, remember, reflects really dated reviews of Section 702 use. On top of being really dated, the report is, as all of these are, heavily redacted and largely boilerplate. Nevertheless, a close read of it (I do think I’m the only one who actually reads these!) can point to trends that can sometimes help identify problems on the same timeline that NSA’s Inspector General does.

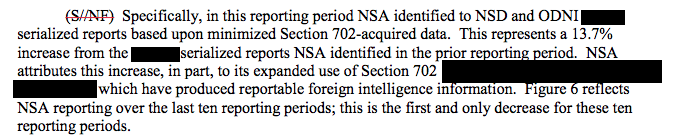

And this most recent Semiannual report, from the period mid-way into implementation of the new USAF CDR function, has this passage (which — I believe — includes a typo).

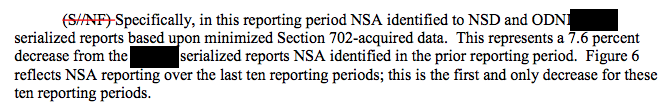

This passage is not reporting a decrease, as the last clause of the paragraph claims; it is reporting an increase in the number of times Section 702 data appears in serialized (that is, finished) reports. The typo appears to be the result of retaining the claim that this is “the first and only decrease of for these ten reporting periods” from the prior report.

What is likely true of this passage, however, is that it is reporting a new trend: “expanded use of Section 702” for some function.

There are several likely candidates for the time period (early 2017). The increasing use of the 2014 exception, the ongoing shift of the old PRTT function (obtaining email metadata) are two.

But another would be to use 702 — such that it is technically feasible — to obtain what metadata exists for encrypted apps. Notably, during precisely this period, Facebook was moving to more closely integrate WhatsApp with its platform generally. And this would give it access (but not content) of chats. Since then, it has probably become easier for Verizon and AT&T to identify who is using Signal by matching the individual keys generated for each contact (just as an example, you can set Verizon to show this or not, meaning they’ve got visibility onto it one way or another). Using 702 to get encrypted app metadata would only give you one degree of separation from a foreign target. But you’d get it with far less oversight than NSA undergoes with Section 215.

Here’s the dirty secret about FISA. It is far easier for NSA to use Section 702 to get content and metadata than it is for NSA to use Section 215 to get just session identifiers.

Section 702 couldn’t replace all of what Section 215 — if it were collecting on the session identifiers associated with encrypted chat apps — gets. But what it could get might be far more voluminous than the 500 million session identifiers collected in 2017.

Update: Bobby Chesney — who seems to know more than he’s letting on — weighs in on the news here.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)