“A Digital Pearl Harbor:” The Ways in Which the Vault 7 Leak Could Have Compromised US and British Assets’ Identities

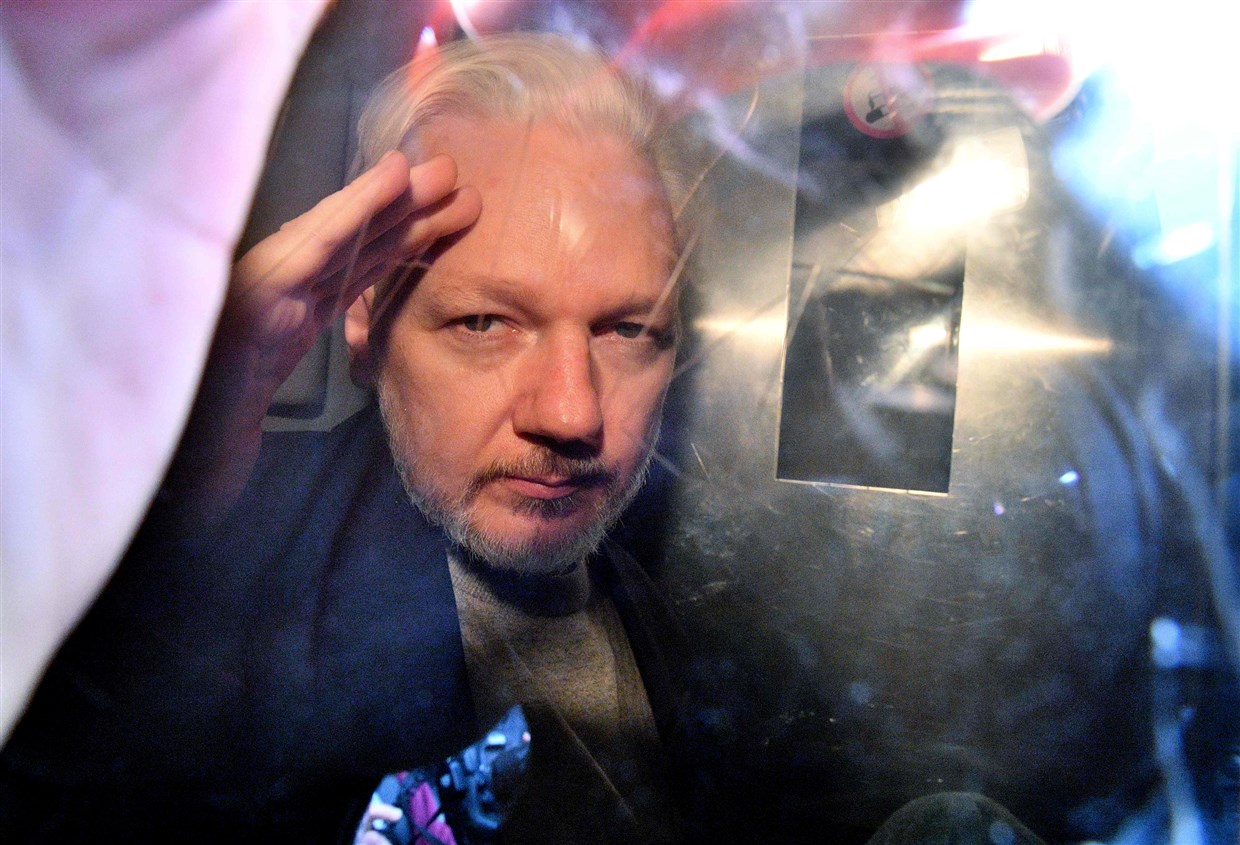

The Julian Assange extradition defense yesterday started presenting evidence that Assange suffers from conditions — Aspergers, depression, and suicidal tendencies — that would make US prisons particularly lethal. It’s the defense that Lauri Love used to avoid extradition, and is Assange’s most likely chance of success. And given our inhumane prisons, it’s a perfectly fair defense against his extradition.

Before that, though, the most interesting evidence submitted by Assange’s team pertained to the three charges that he identified the identities of US and Coalition (and so, British) informants in the Afghan, Iraq, and Cablegate releases. For each of those releases, Assange’s team presented evidence that someone else — Cryptome, in one case, some Guardian journalists in another — released the informants’ identities first. At one point, the lawyer for the US seemed to suggest that Assange had made such disclosures more readily available after the identities had already been published. But Assange can only be extradited for charges that are illegal in the UK as well, and while the UK’s Official Secrets Act explicitly prohibits the publication of covert identities, it does not prohibit republication of names.

In other words, it’s the one evidentiary question where I think WikiLeaks might have the better case (the government has yet to present its own counter-evidence, and Assange has to prove that the charges are baseless to prevent the extradition, so it’s a high hurdle).

The question is particularly interesting for several reasons. Publishing the names of informants is the one charge specifically tied to publication, rather than conspiring to get Chelsea Manning to leak, making it dangerous for journalism in a different way than most of the other charges (save the CFAA charge).

But also because — in a Mike Pompeo screed that many WikiLeaks witnesses have cited completely out of context, in which the then-CIA Director named WikiLeaks a non-state hostile intelligence agency — he accused WikiLeaks of being like Philip Agee, a disillusioned CIA officer who went on to leak the identities of numerous CIA officers who was credibly accused of working with Cuban and Russian intelligence services.

So I thought I’d start today by telling you a story about a bright, well-educated young man. He was described as industrious, intelligent, and likeable, if inclined towards a little impulsiveness and impatience. At some point, he became disillusioned with intelligence work, and angry at his government. He left the government and decided to devote himself to what he regarded as public advocacy: exposing the intelligence officers and operations that he had sworn to keep secret. He appealed to agency employees to send him leads, tips, suggestions. He wrote in a widely-circulated bulletin quote “We are particularly anxious to receive – and anonymously, if you desire – copies of U.S. diplomatic lists and U.S. embassy staff,” end of quote.

That man was Philip Agee, one of the founding members of the magazine CounterSpy, which in its first issue, in 1973, called for the exposure of the CIA undercover operatives overseas. In its September 1974 issue, CounterSpy publicly identified Richard Welch as the CIA station chief in Athens. Later, Richard’s home address and phone number were outed in the press, in Greece. In December 1975, Richard and his wife were returning home from a Christmas party in Athens. When he got out of his car to open the gate in front of his house, Richard Welch was assassinated by a Greek terrorist cell.

At the time of his death, Richard was the highest-ranking CIA officer killed in the line of duty. He had led a rich and honorable life – one that is celebrated with a star on the agency’s memorial wall. He’s buried at Arlington National Cemetery, and has remained dearly remembered by his family and colleagues.

Meanwhile, Philip Agee propped up his dwindling celebrity with an occasional stunt, including a Playboy interview. He eventually settled down as the privileged guest of an authoritarian regime – one that would have put him in front of a firing squad without a second thought had he betrayed its secrets instead of ours.

Today, there are still plenty of Philip Agees in the world, and the harm they inflict on U.S. institutions and personnel is just as serious today as it was back then. They don’t come from the intelligence community, they don’t all share the same background, or use precisely the same tactics as Agee, but they are soulmates. Like him, they choose to see themselves under a romantic light as heroes above the law, saviors of our free and open society. They cling to this fiction even though their disclosures often inflict irreparable harm on both individuals and democratic governments, pleasing despots along the way.

The one thing they don’t share with Agee is the need for a publisher. All they require now is a smartphone and internet access. In today’s digital environment, they can disseminate stolen U.S. secrets instantly around the globe to terrorists, dictators, hackers and anyone else seeking to do us harm.

The reference to Richard Welch is inaccurate (in the same way the claim that WikiLeaks is responsible for release of these informants’ identities could be too). Much of the rest of what Pompeo said was tone-deaf, at best. And that Pompeo — who months earlier had been celebrating WikiLeaks’ cooperation with Russia in interfering in the 2016 election — said this is the kind of breathtaking hypocrisy he specializes in.

Still, I want to revisit Pompeo’s insinuation, made weeks after the release of the Vault 7 files, that Julian Assange is like Philip Agee. The comment struck me at the time, particularly given that the only thing he mentioned to back the claim — also floated during the Chelsea Manning trial — was that WikiLeaks’ releases had helped al-Qaeda.

And as for Assange, his actions have attracted a devoted following among some of our most determined enemies. Following the recent WikiLeaks disclosure, an al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula member posted a comment online thanking WikiLeaks for providing a means to fight America in a way that AQAP had not previously envisioned. AQAP represents one of the most serious threats to our country and around the world today. It’s a group that is devoted not only to bringing down civil passenger planes but our way of life as well. That Assange is the darling of these terrorists is nothing short of reprehensible. Have no doubt that the disclosures in recent years caused harm, great harm, to our nation’s national security, and they will continue to do so for the long term.

They also threaten the trust we’ve developed with our foreign partners when that trust is crucial currency among allies. They risk damaging morale for the good officers at the intelligence community and who take the high road every day. And I can’t stress enough how these disclosures have severely hindered our ability to keep you all safe.

But given what we’ve learned about the Vault 7 release since, I’d like to consider the multiple ways via which the Vault 7 identities could have — and did, in some cases — identify sensitive identities. Pompeo’s a flaming douchebag, and the CIA’s complaint about being targeted like it targets others is unsympathetic, but understanding Pompeo’s analogy to Agee provides some insight into why DOJ charged WikiLeaks in 2017 when it hadn’t in 2013.

Vault 7, justifiably or not, may have changed how the government treated WikiLeaks’ facilitation of the exposure of US intelligence assets.

Before I start, let me emphasize the Vault 7 leak is not charged in the superseding indictment against Assange, and Assange’s treatment of Vault 7 may be radically different than his earlier genuine attempts to at least forestall or delegate the publication of US informant identities. Even if DOJ’s understanding of WikiLeaks’ facilitation of the exposure of US intelligence assets may have changed with the Vault 7 release, DOJ understanding may not be correct. Nor do I think this changes the risk to journalism of the current charges, as charged.

But it may provide insight into why the government did charge those counts, and what a superseding indictment integrating the Vault 7 leak might look like.

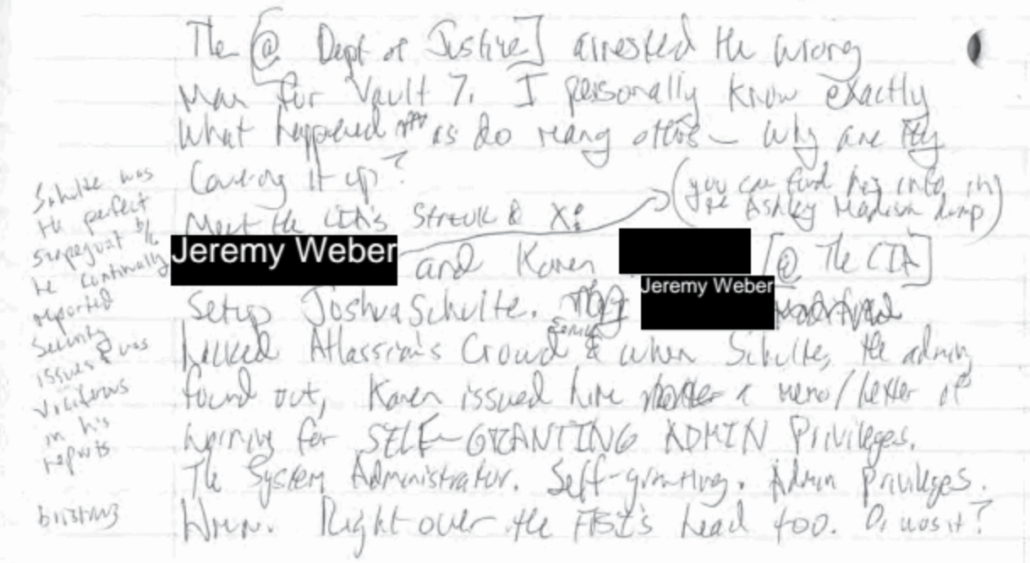

First, although WikiLeaks made a big show of redacting the identities of the coders who developed the CIA’s hacking tools (as they did with the 2010 and 2011 releases), some were left unredacted in the content of the release. That may be unintentional. But the first FBI affidavit against accused Vault 7 leaker Joshua Schulte noted that the pseudonyms of the two other SysAdmins who had access to the files were left unredacted in the first release, something that suggests more intentional disclosure, one that would presumably require the involvement of Schulte or someone else who knew these identities.

i. Names used by the other two CIA Group Systems Administrators were, in fact, published in the publicly released Classified Information.

ii. SCHULTE’s name, on the other hand, was not apparently published in the Classified Inforamtion.

iii. Thus, SCHULTE was the only one of the three Systems Administrators with access to the Classified Information on the Back-Up Server who was not publicly identified via WikiLeaks’s publication of the Classified Information.

A subsequent WikiLeaks release (after the FBI had already made it clear he was a, if not the, suspect) would include Schulte’s username, but I believe that is distinguishable from the release of the other men’s cover names.

Schulte would later threaten to leak more details (including, presumably, either his cover or his real name) on one of those same guys, someone he was particularly angry at, from jail, including the intriguing hint that he had been exposed in the Ashley Madison hack.

At trial, Schulte’s lawyer explained that the leaking he attempted or threatened from jail reflected the anger built up over almost a year of incarceration, but there’s at least some reason to believe that the initial Vault 7 release intentionally exposed the identities of CIA employees whom Schulte had personal gripes with, or at the very least he hoped would be blamed other than him.

Then there’s the damage done to ongoing operations. At trial, one after another CIA witness described the damage the Vault 7 leak had done. While the testimony was typically vague, it was also more stark in terms of scale than what you generally find in CIA trials.

After describing the leak the “equivalent of a digital Pearl Harbor,” for example, Sean Roche, who was the Deputy Director for Digital Innovation at the time of the leak, testified how on the day of the first release, the CIA had to shut down “the vast, vast majority” of operations that used the CIA tools (at a time, of course, when the CIA was actively trying to understand how Russia had attacked the US the prior year), and then CIA had to reach out to those affected.

It was the equivalent of a digital Pearl Harbor.

Q. What do you mean by that?

A. Our capabilities were revealed, and hence, we were not able to operate and our — the capabilities we had been developing for years that were now described in public were decimated. Our operations were immediately at risk, and we began terminating operations; that is, operations that were enabled with tools that were now described and out there and capabilities that were described, information about operations where we’re providing streams of information. It immediately undermined the relationships we had with other parts of the government as well as with vital foreign partners, who had often put themselves at risk to assist the agency. And it put our officers and our facilities, both domestically and overseas, at risk.

Q. Just staying at a very general level, what steps did you take in the immediate aftermath of those disclosures to address those concerns?

A. A task force was formed. Because operations were involved we had to get a team together that did nothing but focus on three things, in this priority order. In an emergency, and that’s what we had, it was operate, navigate, communicate, in that order. So the first job was to assess the risk posture for all of these operations across the world and figure out how to mitigate that risk, and most often, the vast, vast majority we had to back out of those operations, shut them down and create a situation where the agency’s activities would not be revealed, because we are a clandestine agency.

The next part of that was to navigate across all the people affected. It was not just the CIA. There were equities for other government agencies. There were, of course, equities at places and bases across the world, where we had relationships with foreign partners. People heeded immediately, were calling and asking what do I do, what do I say?

And the third part of that was to communicate, which was — in the course of looking at this as a what systemic issues led to the ability to have our information out there — was to document that and write a report that would serve as a lessons learned with the idea of preventing it from ever happening again. [my emphasis]

Notably, given that Assange could be vulnerable to Official Secrets Act charges in the UK if this leak affected any British intelligence officers or assets, Roche mentioned “foreign partners” twice in just this short passage. You don’t get very far down the list of CIA’s foreign partners before you’ve damaged MI6 assets.

Of course, shutting down ongoing operations would not have been enough to protect CIA’s assets. It took just 40 days for Symantec and Kaspersky to publicly identify the tools described in the Vault 7 releases as those found targeting their clients. If the CIA (or its foreign partners) had used human assets to introduce malware into target computers, as a number of these tools required, then those assets might be easily identifiable to the organizations affected.

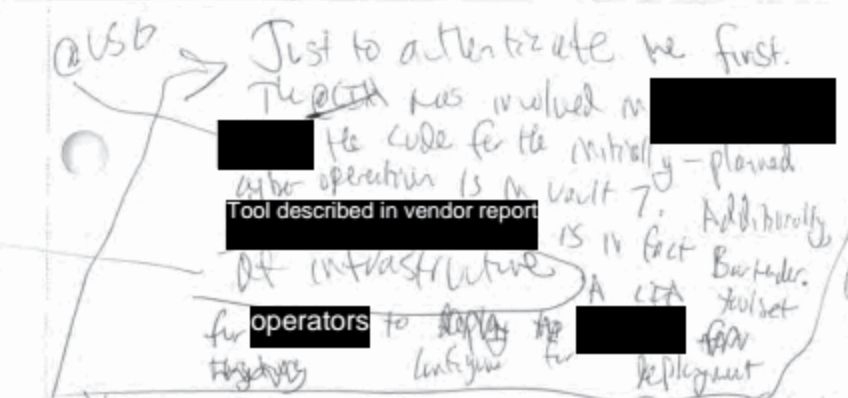

Part of that same leak Schulte attempted from jail explains how this might work. He described how a tool from a particular vendor (which he would have named) was actually “Bartender,” by name presumably a watering hole attack, which had been released in Vault 7.

Had he succeeded in tweeting this out, Schulte would have identified either a cover organization or one in which CIA had recruited assets which was loading malware onto target computers while also loading some kind of vendor software.

I’m not defending CIA’s use of such assets to provide a side-helping of malware when targeted organizations install real software, though all major state-actors do this. But what Schulte (without any known active involvement of WikiLeaks, though he did continue to communicate with WikiLeaks, at least indirectly, while in jail) was allegedly attempting to do was burn either a cover organization or CIA assets, who would have been immediate targets if not exfiltrated. And it provides a good example of what could have happened over and over again on March 7, 2017, when these files were first released.

But there’s one other, possibly even more significant risk.

WikiLeaks has, in the past, preferentially withheld or shared files with Russia and other countries. Most obviously, at least one file hacked as part of the Syria Files which was damning to Russia never got published, and Emma Best claimed recently there were far more. The risk that something like that would have happened in this case is quite real. That’s because the files were leaked at a time when WikiLeaks was actively involved in another Russian operation. There was a ten month delay between the time the files were allegedly shared (in early May 2016) and the time WikiLeaks published them on March 7, 2017. The government has never made any public claim about how they got shared with WikiLeaks. Details of contacts between Guccifer 2.0 and WikiLeaks demonstrate that it would have been impossible to send the volume of data involved in this hack directly to WikiLeaks’ public facing submission system in the time which Schulte did so, and several people familiar with the submission system at the time of that hack have suggested it served more as cover than a functional system. That suggests that Schulte either would have had to have prior contact with WikiLeaks to arrange an alternate upload process, or shared them with WikiLeaks via some third party (notably, Schulte bragged in jail that compressing data to do this efficiently was one of his specialties at CIA).

At trial, even though the government in no way focused on this evidence themselves, there was (inconsistent) evidence that Schulte planned to involve Russia in his efforts to take revenge on the CIA. I’ve heard a related allegation independently.

Remember, too, that WikiLeaks has never published the vast majority of the code for these tools, even though Schulte did leak it, which would make it still easier to identify anyone who had used these tools.

So imagine what might have happened had Russia gotten advance notice (either via WikiLeaks, a WikiLeaks associate, or Schulte himself) of these tools? Russia would have had months — starting well before US intelligence had begun to understand the full extent of the election year operation — to identify any of the CIA tools used against it. To be clear, what follows is speculative (though I’m providing it, in part, because I’m trying to summarize the Vault 7 information so people who are experts on other parts of the Russian treason case can test the theory). But if it had, the aftermath might have looked something like Russia’s prosecution of several FSB officers for treason starting in December 2016. And the response — if CIA recognized that its assets had already been compromised by the Vault 7 release — might look something like the Yahoo indictment charging one of the same FSB officers rolled out, with great fanfare, on March 15, just over a week after the Vault 7 release (DOJ obtained the indictment on February 28, after the CIA knew that WikiLeaks had the release coming and months after the treason arrest, but a week before the actual release). That is, Russia might move to prosecute months before the CIA got specific notice, using the years-old complaints of Pavel Vrublevsky to hide the real reason for the prosecution, and the US might move to disclaim any tie to the FSB officers by criminally prosecuting them and identifying many of the foreign targets they had used Yahoo infrastructure to spy on. Speaking just hypothetically, then, that’s the kind of damage we’d expect if any country — and Russia has been raised here explicitly — got advance access to the CIA tools before the CIA did its damage mitigation starting on March 7, 2017.

This scenario (again, it is speculative at this point) is Spy versus Spy stuff, the kind of thing that state intelligence agencies pull off against each other all the time. But it’s not journalism.

And even the stuff that would have happened after the public release of the CIA files would not just have exposed CIA collection points, but also, probably, some of the human beings who activated those collection points.

WikiLeaks would have you believe that nothing that happened after 2013 could change DOJ’s understanding of those earlier exposures of US (and British) assets.

But the very same Mike Pompeo speech that they’ve all been citing explained precisely what changed.