In response to Chris Murphy’s 15 hour filibuster, Democrats will get a vote on several gun amendments to an appropriations bill, one mandating background checks for all gun purchases, another doing some kind of check to ensure the purchaser is not a known or suspected terrorist.

The latter amendment is Dianne Feinstein’s (see Greg Sargent’s piece on it here). It started as a straight check against the No Fly list (which would not have stopped Omar Mateen from obtaining a gun), but now has evolved. It now says the Attorney General,

may deny the transfer of a firearm if [she] determines, based on the totality of the circumstances, that the transferee represents a threat to public safety based on a reasonable suspicion that the transferee is engaged, or has been engaged, in conduct constituting, in preparation for, in aid of, or related to terrorism, or providing material support or resources therefor.

[snip]

The Attorney General shall establish, within the amounts appropriated, procedures to ensure that, if an individual who is, or within the previous 5 years has been, under investigation for conduct related to a Federal crime of terrorism, as defined in section 2332b(g)(5) of title 18, United States Code, attempts to purchase a firearm, the Attorney General or a designee of the Attorney General shall be promptly notified of the attempted purchase.

The way it would work is a background check would trigger a review of FBI files; if those files showed any “investigation” into terrorism, the muckety mucks would be notified, and they could discretionarily refuse to approve the gun purchase, which they would almost always do for fear of being responsible if something happened.

The purchaser could appeal through the normal appeals process (which goes first to the AG and then to a District Court), but,

such remedial procedures and judicial review shall be subject to procedures that may be developed by the Attorney General to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of information that reasonably could be expected to result in damage to national security or ongoing law enforcement operations, including but not limited to procedures for submission of information to the court ex parte as appropriate, consistent of due process.

Given that an AG recently deemed secret review of Anwar al-Awlaki’s operational activities to constitute enough due process to execute him, the amendment really should be far more specific about this (including requiring the government to use CIPA). When you give the Executive prerogative to withhold information, they tend to do so, well beyond what is adequate to due process.

But there are two other problems with this amendment, one fairly minor, one very significant.

First, minor, but embarrassing, given that Feinstein is on the Senate Judiciary Committee and Ranking Member Pat Leahy is a cosponsor. This amendment doesn’t define what “investigate” means, which is a term of art for the FBI (which triggers each investigative method to which level of investigation you’re at). Given that it is intended to reach someone like Omar Mateen, it must intend to extend to “Preliminary Investigations,” which “may be opened on the basis of any ‘allegation or information’ indicative of possible criminal activity or threats to national security.” Obviously, the Mateen killing shows that someone can exhibit a whole bunch of troubling behaviors and violence yet not proceed beyond the preliminary stage (though I suspect we’ll find the FBI missed a lot of what they should have found, had they not had a preconceived notion of what terrorism looks like and an over-reliance on informants rather than traditional investigation). But in reality, a preliminary investigation is a very very low level of evidence. Yet it would take a very brave AG to approve a gun purchase for someone who had hit a preliminary stage, because if that person were to go onto kill, she would be held responsible.

Also note, though, that I don’t think Syed Rizwan Farook had been preliminarily investigated before his attack last year, though he had been shown to have communicated with someone of interest (which might trigger an assessment). So probably, someone would try to extend it to “assessment” or “lead” stages, which would be an even crazier level of evidence. By not carefully defining what “investigate” means, then, the amendment invites a slippery slope in the future to include those who communicate with people of interest (which is partly what the Terrorist Watch — not No-Fly — list consists of now).

Here’s the bigger problem. As I’ve noted repeatedly, our definition of terrorism (which is the one used in this amendment) includes a whole bunch of biases, which not only disproportionately affect Muslims, but also leave out some of our most lethal kinds of violence. For example, the law treats bombings as terrorist activities, but not mass shootings (so effectively, this law would seem to force actual terrorists into pursuing bombings, because they’d still be able to get those precursors). It is written such that animal rights activists and some environmentalists get treated as terrorists, but not most right wing hate groups. So for those reasons, the law would not reach a lot of scary people with guns who might pose as big a threat as Mateen or Farook.

Worse, the amendment reaches to material support for terrorism, which in practice (because it is almost always applied only for Muslim terrorist groups) has a significantly disproportionate affect on Muslims. In Holder v Humanitarian Law Project, SCOTUS extended material support to include speech, and Muslims have been prosecuted for translating violent videos and even RTing an ISIS tweet. Speech (and travel) related “material support” don’t even have to extend to formal terrorist organizations, meaning certain kinds of anti-American speech or Middle East travel may get you deemed a terrorist.

In other words, this amendment would deprive Muslims simply investigated (possibly even just off a hostile allegation) for possibly engaging in too much anti-American speech of guns, but would not keep guns away from anti-government or anti-choice activists advocating violence.

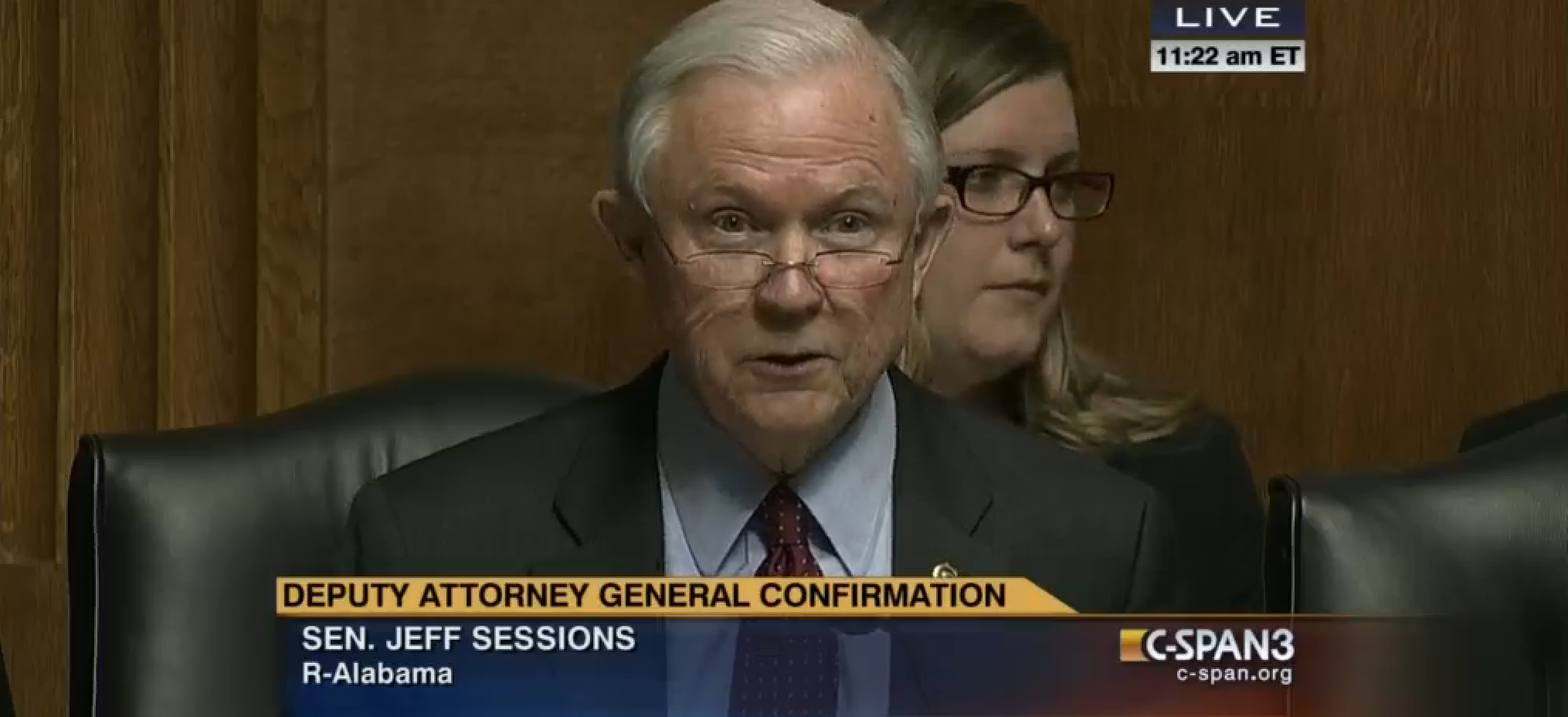

Consider the case of anti-choice Robert Dear, the Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood killer. After a long delay (in part because his mass killing in the name of a political cause was not treated as terrorism), we learned that Dear had previously engaged in sabotage of abortion clinics (which might be a violation of FACE but which is not treated as terrorism), and had long admired clinic killer Paul Hill and the Army of God. Not even Army of God’s ties to Eric Rudolph, the 1996 Olympics bomber, gets them treated as a terrorist group that Dear could then have been deemed materially supporting. Indeed, it was current Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates who chose not to add any terrorism enhancement to Rudolph’s prosecution. Dear is a terrorist, but because his terrorism doesn’t get treated as such, he’d still have been able to obtain guns legally under this amendment.

For a whole lot of political reasons, Muslims engaging in anti-American rants can be treated as terrorists but clinic assassins are not, and because of that, bills like this would not even keep guns out of the hands of some of the most dangerous, organizationally networked hate groups.

Now, I actually have no doubt that Feinstein would like to keep guns out of the hands of people like Robert Dear and — especially given her personal tie to Harvey Milk’s assassination — out of the hands of violent homophobes. But this amendment doesn’t do that. Rather, it predominantly targets just one group of known or suspected “terrorists.” And while the instances of Islamic extremists using guns have increased in recent years (as more men attempt ISIS-inspired killings of soft targets), they are still just a minority of the mass killings in this country.