I’ve been wracking my brain to understand why the Intel Community has been pushing CISA so aggressively.

I get why the Chamber of Commerce is pushing it: because it sets up a regime under which businesses will get broad regulatory immunity in exchange for voluntarily sharing their customers’ data, even if they’re utterly negligent from a security standpoint, while also making it less likely that information their customers could use to sue them would become public. For the companies, it’s about sharply curtailing the risk of (charitably) having imperfect network security or (more realistically, in some cases) being outright negligent. CISA will minimize some of the business costs of operating in an insecure environment.

But why — given that it makes it more likely businesses will wallow in negligence — is the IC so determined to have it, especially when generalized sharing of cyber threat signatures has proven ineffective in preventing attacks, and when there are far more urgent things the IC should be doing to protect themselves and the country?

Richard Burr and Dianne Feinstein’s move the other day to — in the guise of ensuring DHS get to continue to scrub data on intake, instead give the rest of the IC veto power over that scrub (which almost certainly means the bill is substantially a means of eliminating the privacy role DHS currently plays) — leads me to believe the IC plans to use this as they might have used (or might be using) a cyber certification under upstream 702.

Other accounts of upstream 702 and CISA don’t account for John Bates’ 2011 ruling

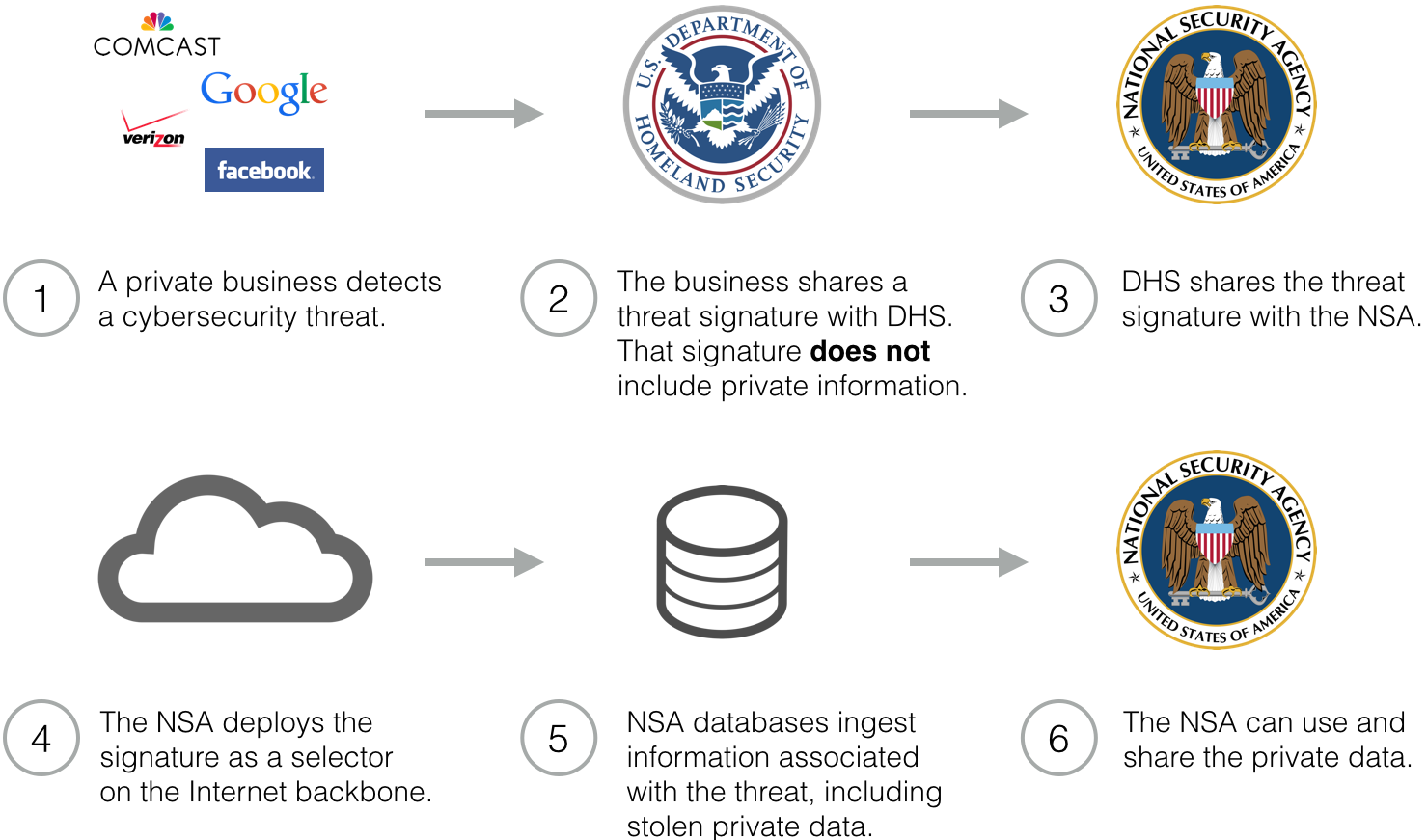

Since NYT and ProPublica caught up to my much earlier reporting on the use of upstream 702 for cyber, people have long assumed that CISA would work with upstream 702 authority to magnify the way upstream 702 works. Jonathan Mayer described how this might work.

This understanding of the NSA’s domestic cybersecurity authority leads to, in my view, a more persuasive set of privacy objections. Information sharing legislation would create a concerning surveillance dividend for the agency.

Because this flow of information is indirect, it prevents businesses from acting as privacy gatekeepers. Even if firms carefully screen personal information out of their threat reports, the NSA can nevertheless intercept that information on the Internet backbone.

Note that Mayer’s model assumes the Googles and Verizons of the world make an effort to strip private information, then NSA would use the signature turned over to the government under CISA to go get the private information just stripped out. But Mayer’s model — and the ProPublica/NYT story — never considered how the 2011 John Bates ruling on upstream collection might hinder that model, particularly as it pertains to domestically collected data.

As I laid out back in June, NSA’s optimistic predictions they’d soon get an upstream 702 certificate for cyber came in the wake of John Bates’ October 3, 2011 ruling that the NSA had illegally collected US person data. Of crucial importance, Bates judged that data obtained in response to a particular selector was intentionally, not incidentally, collected (even though the IC and its overseers like to falsely claim otherwise), even data that just happened to be collected in the same transaction. Crucially, pointing back to his July 2010 opinion on the Internet dragnet, Bates said that disclosing such information, even just to the court or internally, would be a violation of 50 USC 1809(a), which he used as leverage to make the government identify and protect any US person data collected using upstream collection before otherwise using the data. I believe this decision established a precedent for upstream 702 that would make it very difficult for FISC to permit the use of cyber signatures that happened to be collected domestically (which would count as intentional domestic collection) without rigorous minimization procedures.

The government, at a time when it badly wanted a cyber certificate, considered appealing his decision, but ultimately did not. Instead, they destroyed the data they had illegally collected and — in what was almost certainly a related decision — destroyed all the PATRIOT-authorized Internet dragnet data at the same time, December 2011. Bates did permit the government to keep collecting upstream data, but only under more restrictive minimization procedures.

Did FISC approve a cyber certificate but with sharp restrictions on retention and dissemination?

Neither ProPublica/NYT nor Mayer claimed NSA had obtained an upstream cyber certificate (though many other people have assumed it did). We actually don’t know, and the evidence is mixed.

Even as the government was scrambling to implement new upstream minimization procedures to satisfy Bates’ order, NSA had another upstream violation. That might reflect informing Bates, for the first time (there’s no sign they did inform him during the 2011 discussion, though the 2011 minimization procedures may reflect that they already had), they had been using upstream to collect on cyber signatures, or one which might represent some other kind of illegal upstream collection. When the government got Congress to reauthorize FAA that year, it did not inform them they were using or intended to use upstream collection to collect cyber signatures. Significantly, even as Congress began debating FAA, they considered but rejected the first of the predecessor bills to CISA.

My guess is that the FISC did approve cyber collection, but did so with some significant limitations on it, akin to, or perhaps even more restrictive, than the restrictions on multiple communication transactions (MCTs) required in 2011. I say that, in part, because of language in USA F-ReDux (section 301) permitting the government to use information improperly collected under Section 702 if the FISA Court imposed new minimization procedures. While that might have just referred back to the hypothetical 2011 example (in which the government had to destroy all the data), I think it as likely the Congress was trying to permit the government to retain data questioned later.

More significantly, the 2014 NSA, FBI, and CIA minimization procedures contain some version of this language, which appears to be new from the 2011 procedures.

Additionally, nothing in these procedures shall restrict NSA’s ability to conduct vulnerability or network assessments using information acquired pursuant to section 702 of the Act in order to ensure that NSA systems are not or have not been compromised. Notwithstanding any other section in these procedures, information used by NSA to conduct vulnerability or network assessments may be retained for one year solely for that limited purpose. Any information retained for this purpose may be disseminated only in accordance with the applicable provisions of these procedures.

That is, the FISC approved new procedures that permit the retention of vulnerability information for use domestically, but it placed even more restrictions on it (retention for just one year, retention solely for the defense of that agency’s network, which presumably prohibits its use for criminal prosecution, not to mention its dissemination to other agencies, other governments, and corporations) than it had on MCTs in 2011.

To be sure, there is language in both 2011 and 2014 NSA MPs that permits the agency to retain and disseminate domestic communications if it is necessary to understand a communications security vulnerability.

the communication is reasonably believed to contain technical data base information, as defined in Section 2(i), or information necessary to understand or assess a communications security vulnerability. Such communication may be provided to the FBI and/or disseminated to other elements of the United States Government. Such communications may be retained for a period sufficient to allow a thorough exploitation and to permit access to data that are, or are reasonably believed likely to become, relevant to a current or future foreign intelligence requirement. Sufficient duration may vary with the nature of the exploitation.

But at least on its face, that language is about retaining information to exploit (offensively) a communications vulnerability. Whereas the more recent language — which is far more restrictive — appears to address retention and use of data for defensive purposes.

The 2011 ruling strongly suggested that FISC would interpret Section 702 to prohibit much of what Mayer envisioned in his model. And the addition to the 2014 minimization procedures leads me to believe FISC did approve very limited use of Section 702 for cyber security, but with such significant limitations on it (again, presumably stemming from 50 USC 1809(a)’s prohibition on disclosing data intentionally collected domestically) that the IC wanted to find another way. In other words, I suspect NSA (and FBI, which was working closely with NSA to get such a certificate in 2012) got their cyber certificate, only to discover it didn’t legally permit them to do what they wanted to do.

CISA is the new and improved cyber-FISA

And while I’m not certain, I believe that in ensuring that DHS’ scrubs get dismantled, CISA gives the IC a way to do what it would have liked to with a FISA 702 cyber certificate.

Let’s go back to Mayer’s model of what the IC would probably like to do: A private company finds a threat, removes private data, leaving just a selector, after which NSA deploys the selector on backbone traffic, which then reproduces the private data, presumably on whatever parts of the Internet backbone NSA has access to via its upstream selection (which is understood to be infrastructure owned by the telecoms).

But in fact, Step 4 of Mayer’s model — NSA deploys the signature as a selector on the Internet backbone — is not done by the NSA. It is done by the telecoms (that’s the Section 702 cooperation part). So his model would really be private business > DHS > NSA > private business > NSA > treatment under NSA’s minimization procedures if the data were handled under upstream 702. Ultimately, the backbone operator is still going to be the one scanning the Internet for more instances of that selector; the question is just how much data gets sucked in with it and what the government can do once it gets it.

And that’s important because CISA codifies private companies’ authority to do that scan.

For all the discussion of CISA and its definition, there has been little discussion of what might happen at the private entities. But the bill affirmatively authorizes private entities to monitor their systems, broadly defined, for cybersecurity purposes.

(a) AUTHORIZATION FOR MONITORING.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Notwithstanding any other provision of law, a private entity may, for cybersecurity purposes, monitor—

(A) an information system of such private entity;

(B) an information system of another entity, upon the authorization and written consent of such other entity;

(C) an information system of a Federal entity, upon the authorization and written consent of an authorized representative of the Federal entity; and

(D) information that is stored on, processed by, or transiting an information system monitored by the private entity under this paragraph.

(2) CONSTRUCTION.—Nothing in this subsection shall be construed—

(A) to authorize the monitoring of an information system, or the use of any information obtained through such monitoring, other than as provided in this title; or

(B) to limit otherwise lawful activity.

Defining monitor this way:

(14) MONITOR.—The term ‘‘monitor’’ means to acquire, identify, or scan, or to possess, information that is stored on, processed by, or transiting an information system.

That is, CISA affirmatively permits private companies to scan, identify, and possess cybersecurity threat information transiting or stored on their systems. It permits private companies to conduct precisely the same kinds of scans the government currently obligates telecoms to do under upstream 702, including data both transiting their systems (which for the telecoms would be transiting their backbone) or stored in its systems (so cloud storage). To be sure, big telecom and Internet companies do that anyway for their own protection, though this bill may extend the authority into cloud servers and competing tech company content that transits the telecom backbone. And it specifically does so in anticipation of sharing the results with the government, with very limited requirement to scrub the data beforehand.

Thus, CISA permits the telecoms to do the kinds of scans they currently do for foreign intelligence purposes for cybersecurity purposes in ways that (unlike the upstream 702 usage we know about) would not be required to have a foreign nexus. CISA permits the people currently scanning the backbone to continue to do so, only it can be turned over to and used by the government without consideration of whether the signature has a foreign tie or not. Unlike FISA, CISA permits the government to collect entirely domestic data.

Of course, there’s no requirement that the telecoms scan for every signature the government shares with it and share the results with the government. Though both Verizon and AT&T have a significant chunk of federal business — which just got put out for rebid on a contract that will amount to $50 billion — and they surely would be asked to scan the networks supporting federal traffic for those signatures (remember, this entire model of scanning domestic backbone traffic got implicated in Qwest losing a federal bid which led to Joe Nacchio’s prosecution), so they’ll be scanning some part of the networks they operate with the signatures. CISA just makes it clear they can also scan their non-federal backbone as well if they want to. And the telecoms are outspoken supporters of CISA, so we should presume they plan to share promiscuously under this bill.

Assuming they do so, CISA offers several more improvements over FISA.

First — perhaps most important for the government — there are no pesky judges. The FISC gets a lot of shit for being a rubber stamp, but for years judges have tried to keep the government operating in the vicinity of the Fourth Amendment through its role in reviewing minimization procedures. Even John Bates, who was largely a pushover for the IC, succeeded in getting the government to agree that it can’t disseminate domestic data that it intentionally collected. And if I’m right that the FISC gave the government a cyber certificate but sharply limited how it could use that data, then it did so on precisely this issue. Significantly, CISA continues a trend we already saw in USA F-ReDux, wherein the Attorney General gets to decide whether privacy procedures (no longer named minimization procedures!) are adequate, rather than a judge. Equally significant, while CISA permits the use of CISA-collected data for a range of prosecutions, unlike FISA, it requires no notice to defendants of where the government obtained that data.

In lieu of judges, CISA envisions PCLOB and Inspectors General conducting the oversight (as well as audits being possible though not mandated). As I’ll show in a follow-up post, there are some telling things left out of those reviews. Plus, the history of DOJ’s Inspector General’s efforts to exercise oversight over such activities offers little hope these entities, no matter how well-intentioned, will be able to restrain any problematic practices. After all, DOJ’s IG called out the FBI in 2008 for not complying with a 2006 PATRIOT Act Reauthorization requirement to have minimization procedures specific to Section 215, but it took until 2013, with three years of intercession from FISC and leaks from Edward Snowden, before FBI finally complied with that 2006 mandate. And that came before FBI’s current practice of withholding data from its IG and even some information in IG reports from Congress.

In short, given what we know of the IC’s behavior when there was a judge with some leverage over its actions, there is absolutely zero reason to believe that any abuses would be stopped under a system without any judicial oversight. The Executive Branch cannot police itself.

Finally, there’s the question of what happens at DHS. No matter what you think about NSA’s minimization procedures (and they do have flaws), they do ensure that data that comes in through NSA doesn’t get broadly circulated in a way that identifies US persons. The IC has increasingly bypassed this control since 2007 by putting FBI at the front of data collection, which means data can be shared broadly even outside of the government. But FISC never permitted the IC to do this with upstream collection. So any content (metadata was different) on US persons collected under upstream collection would be subjected to minimization procedures.

This CISA model eliminates that control too. After all, CISA, as written, would let FBI and NSA veto any scrub (including of content) at DHS. And incoming data (again, probably including content) would be shared immediately not only with FBI (which has been the vehicle for sharing NSA data broadly) but also Treasury and ODNI, which are both veritable black holes from a due process perspective. And what few protections for US persons are tied to a relevance standard that would be met by virtue of a tie to that selector. Thus, CISA would permit the immediate sharing, with virtually no minimization, of US person content across the government (and from there to private sector and local governments).

I welcome corrections to this model — I presume I’ve overstated how much of an improvement over FISA this program would be. But if this analysis is correct, then CISA would give the IC everything that would have wanted for a cybersecurity certificate under Section 702, with none of the inadequate limits that would have had and may in fact have. CISA would provide an administrative way to spy on US person (domestic) content all without any judicial overview.

All of which brings me back to why the IC wants this this much. In at least one case, the IC did manage to use a combination of upstream and PRISM collection to stop an attempt to steal large amounts of data from a defense contractor. That doesn’t mean it’ll be able to do it at scale, but if by offering various kinds of immunity it can get all backbone providers to play along, it might be able to improve on that performance.

But CISA isn’t so much a cybersecurity bill as it is an Internet domestic spying bill, with permission to spy on a range of nefarious activities in cyberspace, including kiddie porn and IP theft. This bill, because it permits the spying on US person content, may be far more useful for that purpose than preventing actual hacks. That is, it won’t fix the hacking problem (it may make it worse by gutting Federal authority to regulate corporate cyber hygiene). But it will help police other kinds of activity.

If I’m right, the IC’s insistence it needs CISA — in the name of, but not necessarily intending to accomplish — cybersecurity makes more sense.

Update: This post has been tweaked for clarity.

Update, November 5: I should have written this post before I wrote this one. In it, I point to language in the August 26, 2014 Thomas Hogan opinion reflecting earlier approval, at least in the FBI minimization procedures, to share cyber signatures with private entities. The first approval was on September 20, 2012. The FISC approved the version still active in 2014 on August 30, 2013. (See footnote 19.) That certainly suggests FISC approved cyber sharing more broadly than the 2011 opinion might have suggested, though I suspect it still included more restrictions than CISA would. Moreover, if the language only got approved for the FBI minimization procedures, it would apply just to PRISM production, given that the FBI does not (or at least didn’t used to) get unminimized upstream production.