“Linking” Procedures in the Yahoo Opinion

As I mentioned earlier, Yahoo is finally releasing the documents pertaining to its challenge of Protect America Act directives in 2008. The LAT has loaded the Yahoo documents in an easy to access page.

This post will look primarily at the FISCR opinion.

As you’ll recall, this opinion was previously released in 2009 (and in fact, the previous list has names of some of the DOJ people who are redacted with this release unredacted).

The four main new disclosures I noted are:

- A discussion of differences between the definition of foreign power in EO 12333 and FISA

- Concerns Yahoo raised about how inaccurate the first directives it had received (the Court appears to misunderstood the seriousness of the inaccuracies)

- Discussion of a parting shot — this supplemental brief makes it clear the largely redacted discussion pertains to US person data collected overseas; I’ll probably return to this, but it appears Yahoo’s concerns were born out and led to the addition of Sections 703-5 in FISA Amendments Act.

- Reference to “linking” procedures which were part of what FISCR used to deem the collection constitutional

That last item — the “linking” procedures — is what was redacted in this post I did when the memo was first released. As I noted then, the procedures were what the FISCR used to meet particularity requirements.

The following passage starts on page 23:

The linking procedures — procedures that show that the [redacted] designated for surveillance are linked to persons reasonably believed to be overseas and otherwise appropriate targets — involve the application of “foreign intelligence factors” These factors are delineated in an ex parte appendix filed by the government. They also are described, albeit with greater generality, in the government’s brief. As attested by affidavits of the Director of the National Security Agency (NSA), the government identifies [redacted] surveillance for national security purposes on information indicating that, for instance, [big redaction] Although the FAA itself does not mandate a showing of particularity, see 50 U.S.C. § 1805(b). This pre-surveillance procedure strikes us as analogous to and in conformity with the particularly showing contemplated by Sealed Case.

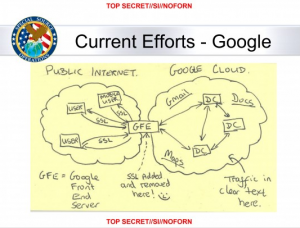

I’ll need to look more closely to find this brief — if it was released. But I suspect that this shows more closely how the metadata dragnets and the content collection are linked. They collect the metadata to mine for “proof” of meaningful connection, then use that to unlock the content. That’s not surprising — it’s what I had been speculating since days after Risen first broke this — but it’s important to flesh out. Because, of course, all this not-a-search metadata really is, because it leads directly to the content.

As I noted in my post in 2009, Russ Feingold released a statement with the release of the opinion, basically arguing that Yahoo could have won this if they had had access to the procedures related to the program (Mark Zwillinger made the same point when he testified to PCLOB).

The decision placed the burden of proof on the company to identify problems related to the implementation of the law, information to which the company did not have access. The courtupheld the constitutionality of the PAA, as applied, without the benefit of an effective adversarial process. The court concluded that “[t]he record supports the government. Notwithstanding the parade of horribles trotted out by the petitioner, it has presented no evidence of any actual harm, any egregious risk of error, or any broad potential for abuse in the circumstances of the instant case.” However, the company did not have access to all relevant information, including problems related to the implementation of the PAA. Senator Feingold, who has repeatedly raised concerns about the implementation of the PAA and its successor, the FISA Amendments Act (“FAA”), in classified communications with the Director of National Intelligence and the Attorney General, has stated that the court’s analysis would have been fundamentally altered had the company had access to this information and been able to bring it before the court.

There’s no reason to believe the “linking” procedures are what Feingold was referring to. After all, there still are details of the minimization and targeting procedures that raise big constitutional issues. Plus, we know foreign collection has always been a big concern of Feingold’s. But I am wondering whether part of the problem was that their contact chaining was not very good, and therefore they were collecting people who really weren’t linked to the targets in question.

Which might explain why Yahoo was experiencing so many dud directives in the first months of its operation.