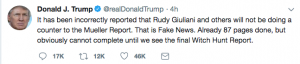

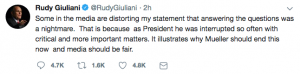

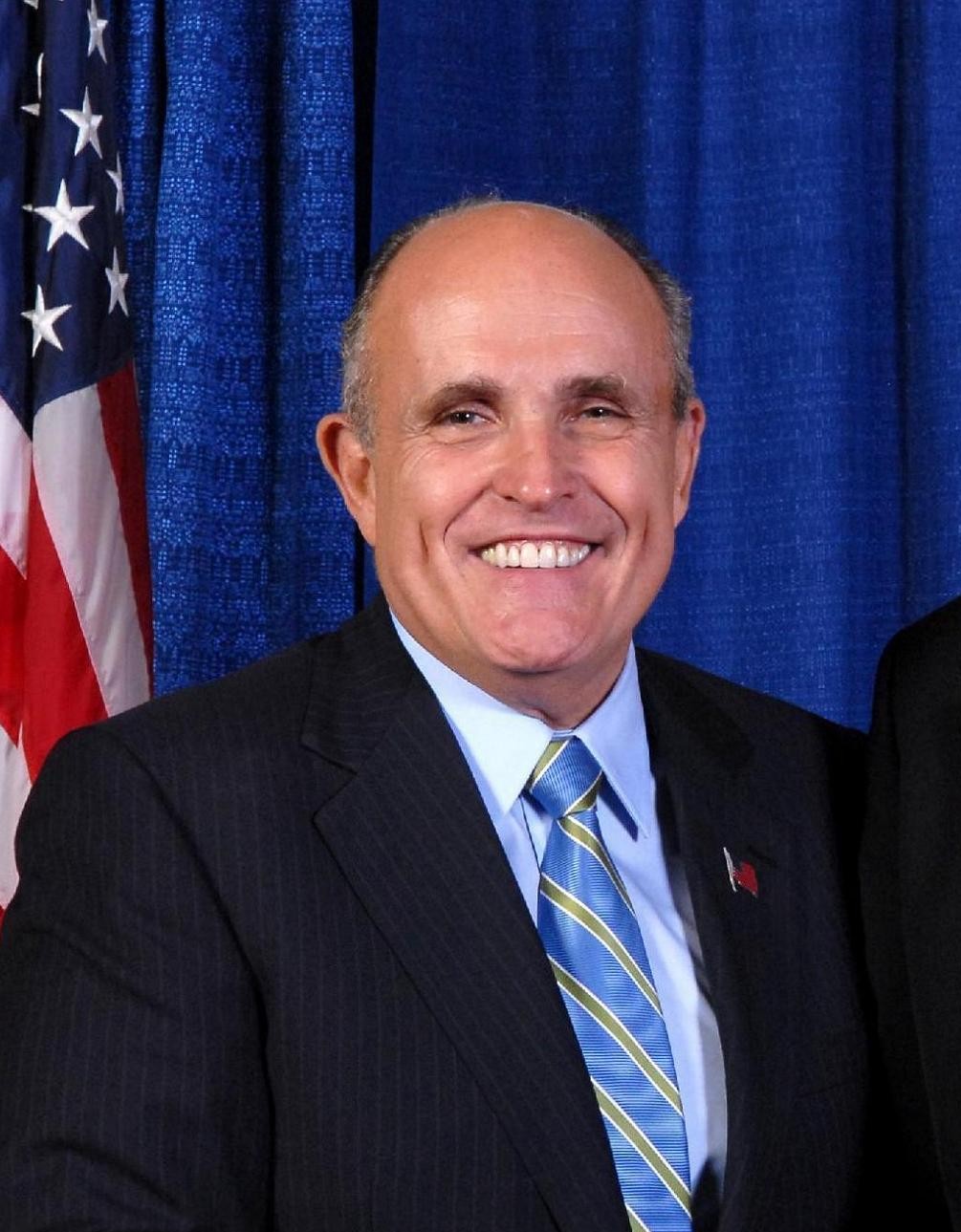

In an interview last week, Rudy Giuliani explained that Trump had finished the open book test Mueller had given the President, but that they were withholding the answers until after tomorrow’s election, after which they’ll re-enter negotiations about whether Trump will actually answer questions on the Russian investigation in person or at all.

“I expect a day after the election we will be in serious discussions with them again, and I have a feeling they want to get it wrapped up one way or another.”

Meanwhile, one of the first of the post-election Administration shake-up stories focuses, unsurprisingly, on the likelihood that Trump will try to replace Jeff Sessions and/or Rod Rosenstein (though doesn’t headline the entire story “Trump set to try to end Mueller investigation,” as it should).

Some embattled officials, including Attorney General Jeff Sessions, are expected to be fired or actively pushed out by Trump after months of bitter recriminations.

[snip]

Among those most vulnerable to being dismissed are Sessions and Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein, who is overseeing special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s Russia investigation after Sessions recused himself. Trump has routinely berated Sessions, whom he faults for the Russia investigation, but he and Rosenstein have forged an improved rapport in recent months.

As I note in my TNR piece on the subject, there are several paths that Trump might take to attempt to kill the Mueller investigation, some of which might take more time and elicit more backlash. If Trump could convince Sessions to resign, for example, he could bring in Steven Bradbury or Alex Azar to replace him right away, meaning Rosenstein would no longer be Acting Attorney General overseeing Mueller, and they could do whatever they wanted with it (and remember, Bradbury already showed himself willing to engage in legally suspect cover-ups in hopes of career advancement with torture). Whereas firing Rosenstein would put someone else — Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who already obtained an ethics waiver for matters pertaining to Trump Campaign legal firm Jones Day, though it is unclear whether that extends to the Mueller investigation — in charge of overseeing Mueller immediately.

This may well be why Rudy is sitting on Trump’s open book test: because they’ve gamed out several possible paths depending on what kind of majority, if any, Republicans retain in the Senate (aside from trying to defeat African American gubernatorial candidates in swing states, Trump has focused his campaigning on retaining the Senate; FiveThirtyEight says the two most likely outcomes are that Republicans retain the same number of seats or lose just one, net). But they could well gain a few seats. If they have the numbers to rush through a Sessions replacement quickly, they’ll fire him, but if not, perhaps Trump will appease Mueller for a few weeks by turning in the answers to his questions.

That’s the background to what I focused on in my TNR piece last week: the Mueller report that Rudy has been talking about incessantly, in an utterly successful attempt to get most journalists covering this to ignore the evidence in front of them that Mueller would prefer to speak in indictments, might, instead, be the failsafe, the means by which Mueller would convey the fruits of his investigation to the House Judiciary Committee if Trump carries out a Wednesday morning massacre. And it was with that in mind that I analyzed how the Watergate Road Map served to do just that in this post.

In this post, I’d like to push that comparison further, to see what — if Mueller and his Watergate prosecutor James Quarles team member are using the Watergate precedent as a model — that might say about Mueller’s investigation. I’ll also lay out what a Mueller Road Map, if one awaits a Wednesday Morning Massacre in a safe somewhere, might include.

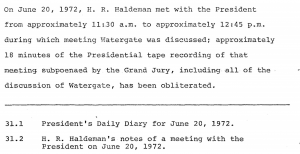

The Watergate prosecutors moved from compiling evidence to issuing the Road Map in just over six months

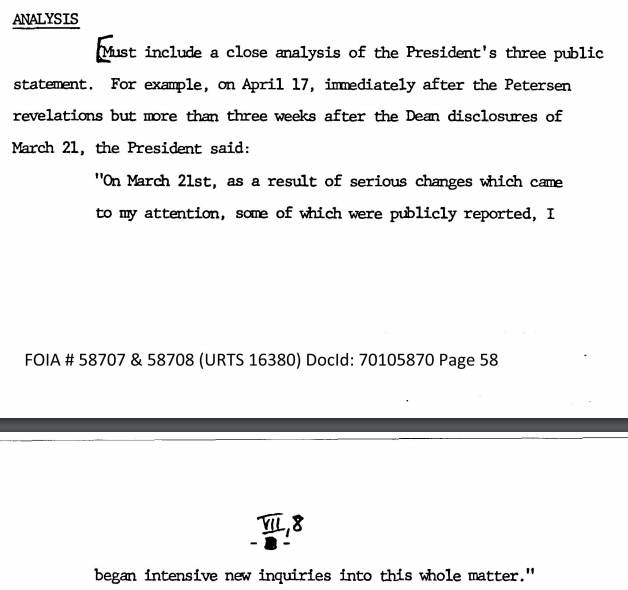

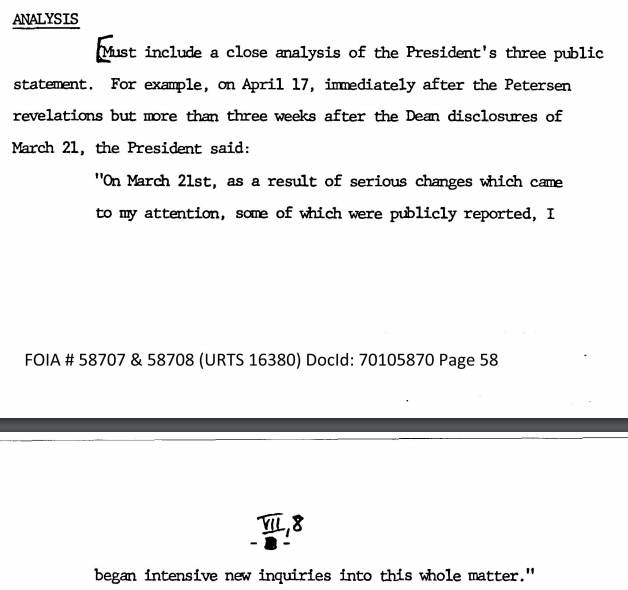

As early as August 1973, George Frampton had sent Archibald Cox a “summary of evidence” against the President. Along with laying out the gaps prosecutors had in their evidence about about what Nixon knew (remember, investigators had only learned of the White House taping system in July), it noted that any consideration of how his actions conflicted with his claims must examine his public comments closely.

That report paid particular attention to how Nixon’s White House Counsel had created a report that created a transparently false cover story. It described how Nixon continued to express full confidence in HR Haldeman and John Ehrlichman well after he knew they had been involved in the cover-up. It examined what Nixon must have thought the risks an investigation posed.

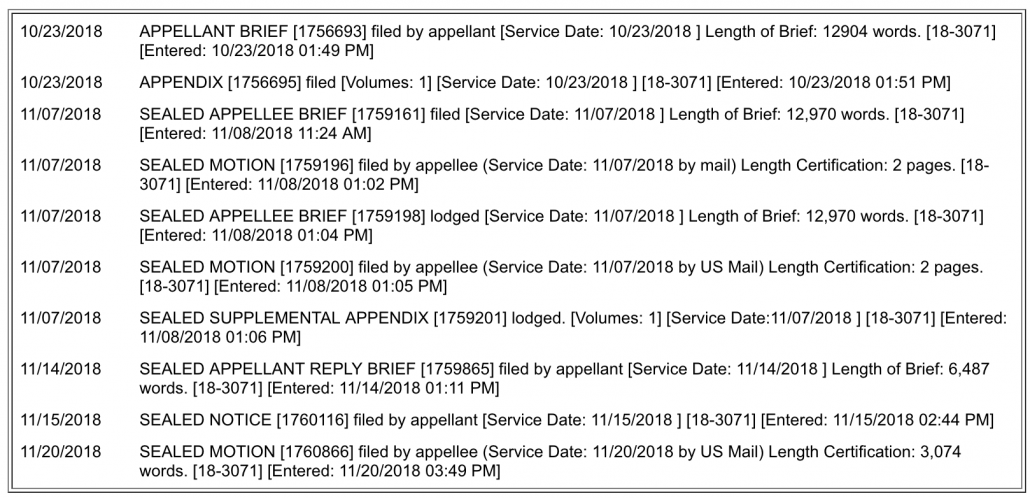

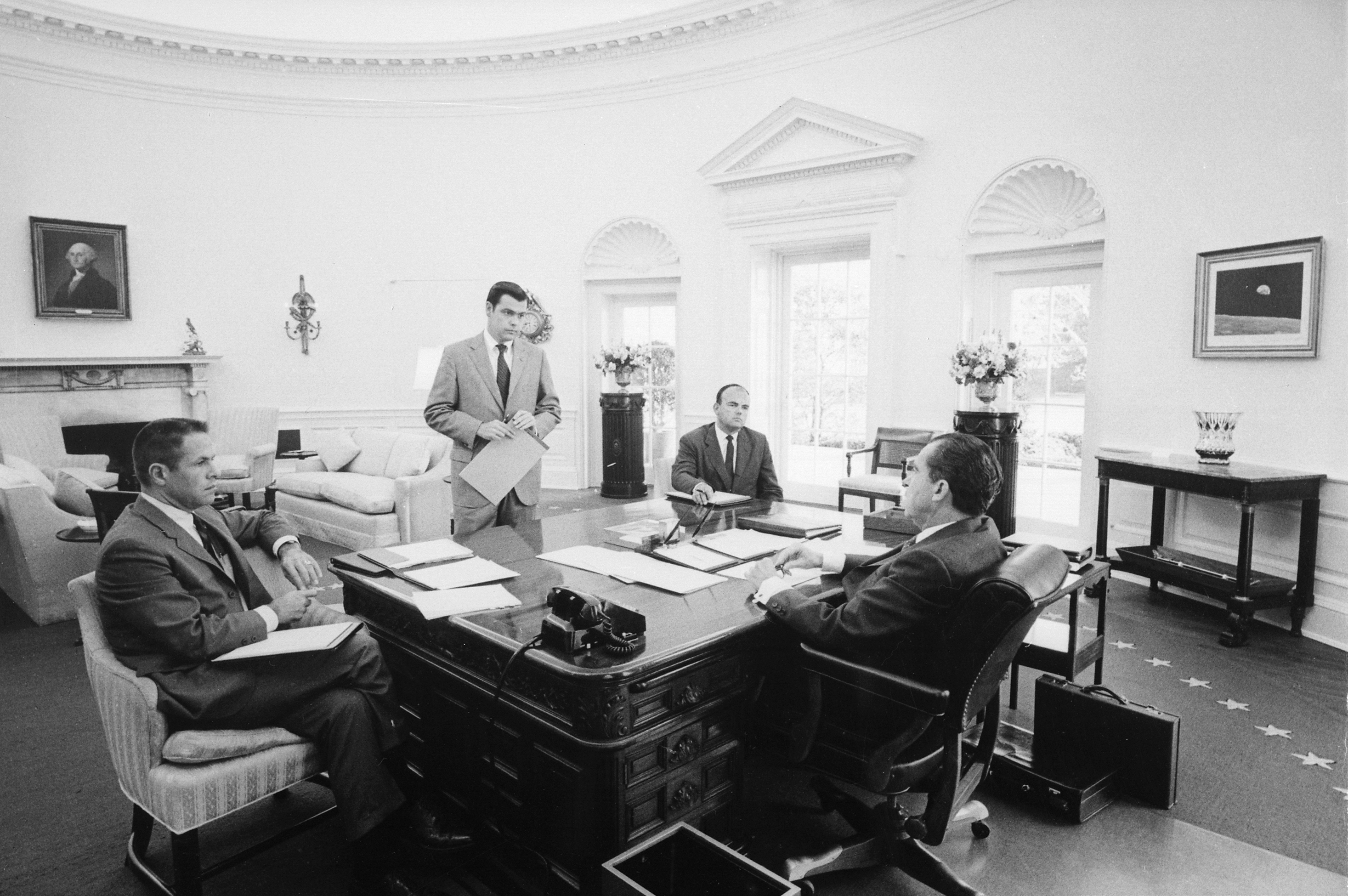

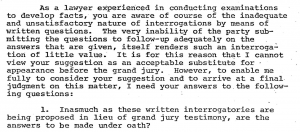

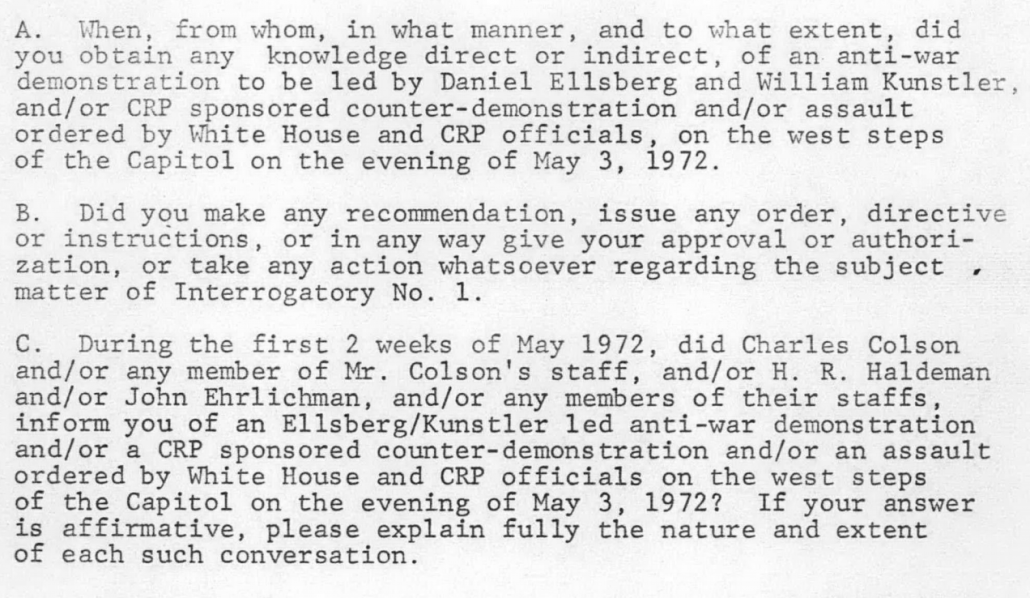

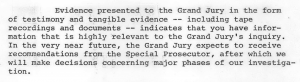

The Archives’ Road Map materials show that in the same 10 day period from January 22 to February 1, 1974 when the Special Prosecutor’s office was negotiating with the President’s lawyers about obtaining either his in-person testimony or at least answers to interrogatories, they were also working on a draft indictment of the President, charging four counts associated with his involvement in and knowledge of the bribe to Howard Hunt in March 1973. A month later, on March 1, 1974 (and so just 37 days after the time when Leon Jaworski and Nixon’s lawyers were still discussing an open book test for that more competent president), the grand jury issued the Road Map, a request to transmit grand jury evidence implicating the President to the House Judiciary Committee so it could be used in an impeachment.

Toto we’re not in 1974 anymore … and neither is the President

Let me clear about what follows: there’s still a reasonable chance Republicans retain the House, and it’s most likely that Republicans will retain the Senate. We’re not in a position where — unless Mueller reveals truly heinous crimes — Trump is at any imminent risk of being impeached. We can revisit all this on Wednesday after tomorrow’s elections and after Trump starts doing whatever he plans to do in response, but we are in a very different place than we were in 1974.

So I am not predicting that the Mueller investigation will end up the way the Watergate one did. Trump has far less concern for his country than Nixon did — an observation John Dean just made.

And Republicans have, almost but not quite universally, shown little appetite for holding Trump to account.

So I’m not commenting on what will happen. Rather, I’m asking how advanced the Mueller investigation might be — and what it may have been doing for the last 18 months — if it followed the model of the Watergate investigation.

One more caveat: I don’t intend to argue the evidence in this thread — though I think my series on what the Sekulow questions say stands up really well even six months later. For the rest of this post, I will assume that Mueller has obtained sufficient evidence to charge a conspiracy between Trump’s closest aides and representatives of the Russian government. Even if he doesn’t have that evidence, though, he may still package up a Road Map in case he is fired.

Jaworski had a draft indictment around the same time he considered giving Nixon an open book test

Even as the Watergate team was compiling questions they might pose to the President if Jaworski chose to pursue that route, they were drafting an indictment.

If the Mueller investigation has followed a similar path, that means that by the time Mueller gave Trump his open book test in October, he may have already drafted up an indictment covering Trump’s actions. That’s pretty reasonable to imagine given Paul Manafort’s plea deal in mid-September and Trump’s past statements about how his former campaign manager could implicate him personally, though inconsistent with Rudy’s claims (if we can trust him) that Manafort has not provided evidence against Trump.

Still, if the Jaworski Road Map is a guide, then Mueller’s team may have already laid out what a Trump indictment would look like if you could indict a sitting President. That said, given the complaints that DOJ had drafted a declination with Hillary before her interview, I would assume they would keep his name off it, as the Watergate team did in editing the Nixon indictment.

Then, a month after drawing up a draft indictment, Jaworski’s grand jury had a Road Map all packaged up ready to be sent to HJC.

Another crucial lesson of this comparison: Jaworksi did not wait for, and did not need, testimony from the President to put together a Road Map for HJC. While I’m sure he’ll continue pursuing getting Trump on the record, there’s no reason to believe Mueller needs that to provide evidence that Trump was part of this conspiracy to HJC.

Given that I think a Mueller report primarily serves as a failsafe at this point, I would expect that he would have some version of that ready to go before Wednesday. And that’s consistent with the reports — enthusiastically stoked by the President’s lawyers — that Mueller is ready to issue his findings.

If a Mueller report is meant to serve as a Road Map for an HJC led by Jerrold Nadler starting in January, then it is necessarily all ready to go (and hopefully copied and safely stored in multiple different locations), even if it might be added to in coming months.

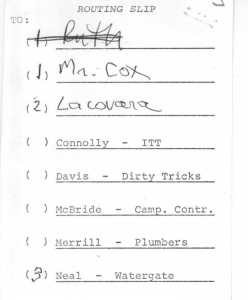

The Road Map Section I included evidence to substantiate the the conspiracy

As I laid out here, the Watergate Road Map included four sections:

I. Material bearing on a $75,000 payment to E. Howard Hunt and related events

II. Material bearing on the President’s “investigation”

III. Material bearing on events up to and including March 17, 1973

IV. The President’s public statements and material before the grand jury related thereto

The first section maps very closely to the overt acts laid out in the February 1 draft indictment, incorporating two acts into one and leaving off or possibly redacting one, but otherwise providing the grand jury evidence — plus some interim steps in the conspiracy — that Jaworski would have used to prove all the overt acts charged in the conspiracy charge from that draft indictment.

If Mueller intended to charge a quid pro quo conspiracy — that Trump accepted a Russian offer to drop dirt, possibly emails explicitly, in response for sanctions relief (and cooperation on Syria and other things) — then we could imagine the kinds of overt acts he might use to prove that:

- Foreknowledge of an offer of dirt and possibly even emails (Rick Gates and Omarosa might provide that)

- Trump involvement in the decision to accept that offer (Paul Manafort had a meeting with Trump on June 7, 2016 that might be relevant, as would the immediate aftermath of the June 9 meeting)

- Trump signaling that his continued willingness to deliver on the conspiracy (as early as the George Papadopoulos plea, Mueller laid out some evidence of this, plus there is Trump’s request for Russia to find Hillary emails, which Mueller has already shown was immediately followed by intensified Russian hacking attempts)

- Evidence Russia tailored releases in response to Trump campaign requests (Roger Stone may play a key role in this, but Mueller appears to know that Manafort even more explicitly asked Russia for help)

- Evidence Trump moved to pay off his side of the deal, both by immediately moving to cooperate on Syria and by assuring Russia that the Trump Administration would reverse Obama’s sanctions

Remember, to be charged, a conspiracy does not have to have succeeded (that is, it doesn’t help Trump that he hasn’t yet succeeded in paying off his debt to Russia; it is enough that he agreed to do so and then took overt acts to further the conspiracy).

In other words, if Mueller has a Road Map sitting in his safe, and if I’m right that this is the conspiracy he would charge, there might be a section that included the overt acts that would appear in a draft indictment of Trump (and might appear in an indictment of Trump’s aides and spawn and the Russian representatives they conspired with), along with citations to the grand jury evidence Mueller has collected to substantiate those overt acts.

Note, this may explain whom Mueller chooses to put before the grand jury and not: that it’s based off what evidence Mueller believes he would need to pass on in sworn form to be of use for HJC, to (among other things) help HJC avoid the protracted fights over subpoenas they’ll face if Democrats do win a majority.

The Road Map Section II described how the White House Counsel tried to invent a cover story

After substantiating what would have been the indictment against Nixon, the Watergate Road Map showed how Nixon had John Dean and others manufacture a false exonerating story. The Road Map cited things like:

- Nixon’s public claims to have total confidence in John Dean

- Nixon’s efforts to falsely claim to the Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst, that former AG John Mitchell might be the most culpable person among Nixon’s close aides

- Nixon’s instructions to his top domestic political advisor, John Ehrlichman, to get involved in John Dean’s attempts to create an exculpatory story

- Press Secretary Ron Ziegler’s public lies that no one knew about the crime

- Nixon’s efforts to learn about what prosecutors had obtained from his close aides

- Nixon’s private comments to his White House Counsel to try to explain away an incriminating comment

- Nixon’s ongoing conversations with his White House Counsel about what he should say publicly to avoid admitting to the crime

- Nixon’s multiple conversations with top DOJ official Henry Petersen, including his request that Peterson not investigate some crimes implicating the Plumbers

- Nixon’s orders to his Chief of Staff, HR Haldeman, to research the evidence implicating himself in a crime

This is an area where there are multiple almost exact parallels with the investigation into Trump, particularly in Don McGahn’s assistance to the President to provide bogus explanations for both the Mike Flynn and Jim Comey firings — the former of which involved Press Secretary Sean Spicer and Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, the latter of which involved Trump’s top domestic political advisor Stephen Miller. There are also obvious parallels between the Petersen comments and the Comey ones. Finally, Trump has made great efforts to learn via Devin Nunes and other House allies what DOJ has investigated, including specifically regarding the Flynn firing.

One key point about all this: the parallels here are almost uncanny. But so is the larger structural point. These details did not make the draft Nixon indictment. There were just additional proof of his cover-up and abuse of power. The scope of what HJC might investigate regarding presidential abuse is actually broader than what might be charged in an indictment.

The equivalent details in the Mueller investigation — particularly the Comey firing — have gotten the bulk of the press coverage (and at one point formed a plurality of the questions Jay Sekulow imagined Mueller might ask). But the obstruction was never what the case in chief is, the obstruction started when Trump found firing Flynn to be preferable to explaining why he instructed Flynn, on December 29, to tell the Russians not to worry about Obama’s sanctions. In the case of the Russia investigation, there has yet to be an adequate public explanation for Flynn’s firing, and the Trump team’s efforts to do so continue to hint at the real exposure the President faces on conspiracy charges.

In other words, I suspect that details about the Comey firing and Don McGahn’s invented explanations for it that made a Mueller Road Map might, as details of the John Dean’s Watergate investigation did in Jaworski’s Road Map, as much to be supporting details to the core evidence proving a conspiracy.

The Road Map Section III provided evidence that Nixon knew about the election conspiracy, and not just the cover-up

The third section included some of the most inflammatory stuff in Jaworski’s Road Map, showing that Nixon knew about the campaign dirty tricks and describing what happened during the 18 minute gap. Here’s where I suspect Jaworski’s Road Map may differ from Mueller’s: while much of this section provides circumstantial evidence to show that the President knew about the election crimes ahead of time, my guess is (particularly given Manafort’s plea) that Mueller has more than circumstantial evidence implicating Trump. In a case against Trump, the election conspiracy — not the cover-up, as it was for Nixon — is the conspiracy-in-chief that might implicate the President.

The Road Map Section III described Nixon’s discussions about using clemency to silence co-conspirators

One other area covered by this section, however, does have a direct parallel: in Nixon’s discussions about whether he could provide clemency to the Watergate defendants. With both Flynn and Manafort cooperating, Mueller must have direct descriptions of Trump’s pardon offers. What remains to be seen is if Mueller can substantiate (as he seems to be trying to do) Trump willingness to entertain any of the several efforts to win Julian Assange a pardon. There’s no precedent to treat offering a pardon as a crime unto itself, but it is precisely the kind of abuse of power the founders believed merited impeachment. Again, it’s another thing that might be in a Mueller Road Map that wouldn’t necessarily make an indictment.

The Road Map Section IV showed how Nixon’s public comments conflicted with his actions

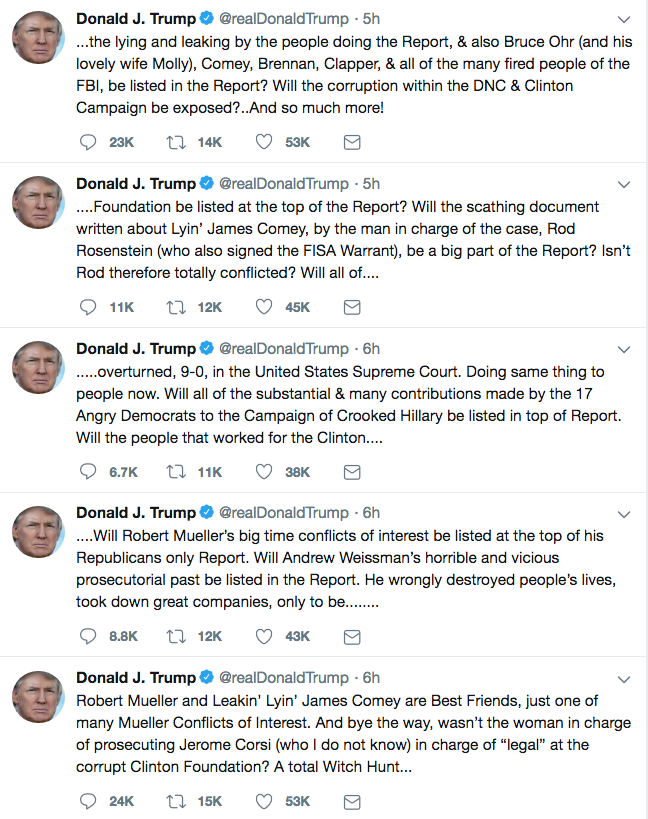

We have had endless discussions about Trump’s comments about the Russian investigation on Twitter, and even by March, at least 8 of the questions Sekulow imagined Mueller wanted to ask pertained to Trump’s public statements.

- What was the purpose of your April 11, 2017, statement to Maria Bartiromo?

- What did you mean when you told Russian diplomats on May 10, 2017, that firing Mr. Comey had taken the pressure off?

- What did you mean in your interview with Lester Holt about Mr. Comey and Russia?

- What was the purpose of your May 12, 2017, tweet?

- What was the purpose of the September and October 2017 statements, including tweets, regarding an investigation of Mr. Comey?

- What is the reason for your continued criticism of Mr. Comey and his former deputy, Andrew G. McCabe?

- What was the purpose of your July 2017 criticism of Mr. Sessions?

- What involvement did you have in the communication strategy, including the release of Donald Trump Jr.’s emails?

The Watergate Road Map documents a number of public Nixon comments that, like Trump’s, are not themselves criminal, but are evidence the President was lying about his crimes and cover-up. The Watergate Road Map describes Nixon claiming that:

- He did not know until his own investigation about efforts to pay off Watergate defendants

- He did not know about offers of clemency

- He did not know in March 1973 there was anything to cover up

- His position has been to get the facts out about the crime, not cover them up

- He ordered people to cooperate with the FBI

- He had always pressed to get the full truth out

- He had ordered legitimate investigations into what happened

- He had met with Kleindienst and Peterson to review what he had learned in his investigation

- He had not turned over evidence of a crime he knew of to prosecutors because he assumed Dean already had

- He had learned more about the crimes between March and April 1973

Admittedly, Trump pretended to want real investigations — an internal investigation of what Flynn had told the FBI, and an external investigation into the election conspiracy — for a much briefer period than Nixon did (his comments to Maria Bartiromo, which I covered here, and Lester Holt, which I covered here, are key exceptions).

Still, there are a slew of conflicting comments Trump has made, some obviously to provide a cover story or incriminate key witnesses, that Mueller showed some interest in before turning in earnest to finalizing the conspiracy case in chief. A very central one involves the false claims that Flynn had said nothing about sanctions and that he was fired for lying to Mike Pence about that; probably at least 7 people knew those comments were false when Sean Spicer made them. Then there are the at least 52 times he has claimed “No Collusion” or the 135 times he has complained about a “Witch Hunt” on Twitter.

Trump’s lawyers have complained that his public comments have no role in a criminal investigation (though the likelihood he spoke to Putin about how to respond as the June 9 meeting story broke surely does). But Mueller may be asking them for the same reason they were relevant to the Watergate investigation. They are evidence of abuse of power.

The Road Map included the case in chief, not all the potential crimes

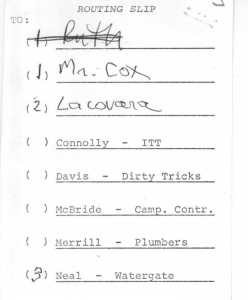

Finally, there is one more important detail about the Road Map that I suspect would be matched in any Mueller Road Map: Not all the crimes the Special Prosecutor investigated made the Road Map. The Watergate team had a number of different task forces (as I suspect Mueller also does). And of those, just Watergate (and to a very limited degree, the cover-up of the Plumbers investigation) got included in the Road Map.

Here, we’ve already seen at least one crime get referred by Mueller, Trump’s campaign payoffs. I’ve long suggested that the Inauguration pay-to-play might also get referred (indeed, that may be the still-active part of the grand jury investigation that explains why SDNY refuses to release the warrants targeting Michael Cohen). Mueller might similarly refer any Saudi, Israeli, and Emirate campaign assistance to a US Attorney’s office for investigation. And while it’s virtually certain Mueller investigated the larger network of energy and other resource deals that seem to be part of what happened at the Seychelles meetings, any continuing investigation may have been referred (indeed, may have actually derived from) SDNY.

In other words, while a Mueller Road Map might include things beyond what would be necessary for a criminal indictment, it also may not include a good number of things we know Mueller to have examined, at least in passing.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.