As I noted Wednesday, Mike Flynn’s legal team and the government submitted a bunch of filings.

In this post, I suggested (controversially) that prosecutors may have had a different purpose for raising probation in their reply to Flynn’s sentencing memo, to remind Judge Emmet Sullivan how pissed he gets when powerful people demand special treatment that the little people go to prison for. In this post, I suggested that Flynn’s motion to dismiss would be better suited if Sidney Powell were representing Carter Page, not Flynn.

In this post, I’ll cover the meat of the issue, Flynn’s attempt to withdraw his guilty plea, made twice, under oath.

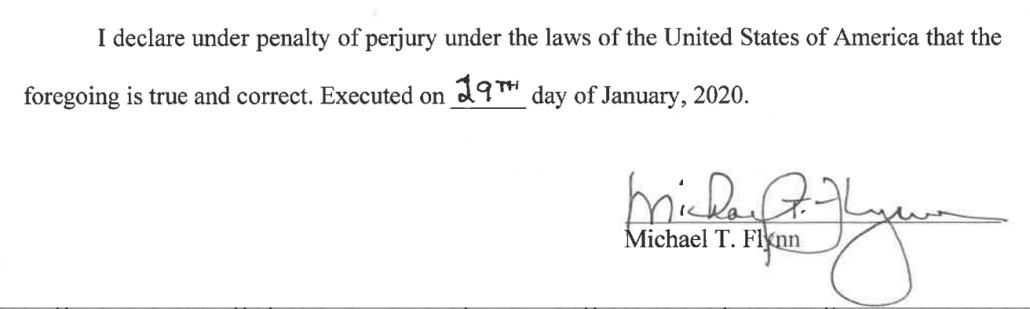

Before I get into that meat, though, note that with a sworn declaration Flynn submitted with this filing, he has given four sworn statements in this matter:

- December 1, 2017: Mike Flynn pled guilty before Judge Rudolph Contreras to lying in a January 24, 2017 FBI interview.

- December 18, 2018: Mike Flynn reallocuted his guilty plea before Judge Emmet Sullivan to lying in a January 24, 2017 FBI interview.

- June 26, 2018: Mike Flynn testified to an EDVA grand jury, among other things, that “from the beginning,” his 2016 consulting project “was always on behalf of elements within the Turkish government,” he and Bijan Kian would “always talk about Gulen as sort of a sharp point” in relations between Turkey and the US as part of the project (though there was some discussion about business climate), and he and his partner “didn’t have any conversations about” a November 8, 2016 op-ed published under his name until “Bijan [] sent me a draft of it a couple of days prior, maybe about a week prior.” The statements conflict with a FARA filing submitted under Flynn’s name.

- January 29, 2020: Mike Flynn declared, under oath that, “in truth, I never lied.”

Understand that from the moment Judge Emmet Sullivan picks up this motion to withdraw his plea, Sullivan will be faced with Flynn claiming he lied, at least once, under oath. Take your pick which one of these statements under oath Flynn now claims to be a lie, but at least one of them necessarily is. And Sullivan has made it clear he plans to put Flynn back under oath to resolve all this.

That’s the hole that Sidney Powell has crafted for her client to dig his way out of, a sworn statement that conflicts with two earlier ones, and sworn testimony that conflicts with her primary basis for withdrawing this plea.

Almost no mention of his lies about Russia

From there, she provides her client little help from the primary task before him: explaining why he is withdrawing his guilty plea that primarily relates to his January 24, 2017 FBI interview. In the first paragraph of her motion, she asserts that Mike Flynn does maintain he did not lie on January 24, 2017, meaning he lied under oath before both Contreras and Sullivan when he said he did.

Michael T. Flynn (“Mr. Flynn”) does maintain that he is innocent of the 18 U.S.C. §1001 charges; and he did not lie to the FBI agents who interviewed him in the White House on January 24, 2017.

She offers several different explanations for why her client apparently perjured himself twice before judges. The most sustained one — one Flynn fans have made persistently — is that he now thinks the agents didn’t actually believe he lied because they “saw no indications of deception” from Flynn, meaning that he didn’t act like he was lying. Bizarrely, one of the things Flynn includes in his sworn declaration is that he has a history of not being candid about sensitive and classified subjects with anyone who is not his superior (though I would imagine that his former superior James Clapper would argue even this is not true).

My baseline reaction to questions posed by people outside of my superiors, immediate command, or office of responsibility is to protect sensitive or classified information, except upon “need to know” and the proper level of security clearance. That type of filter is ingrained in me and virtually automatic after a lifetime of honoring my duty to protect the most important national and military secrets.

In short, Flynn claims under oath that he has a habit of not telling the truth about classified or sensitive matters. He doesn’t quite say that’s what happened here, but since he has stated under oath he knew that it was a crime to lie to the FBI and he knew the people interviewing him would have had access to transcripts of his calls with Sergei Kislyak, has has provided evidence, under oath, that he knew these FBI agents were people he had to tell the truth to and were included among those with the “need to know” about what he said to Kislyak. But the explanation that he has a virtually automatic filter that leads him not to tell the truth about sensitive information does explain why agents might observe that he had a sure demeanor even while knowing he lied: Flynn has had a lot of practice lying.

Now, this by itself surely can’t get him out of his conflicting sworn statements that he didn’t lie but he did.

So Flynn blames his former lawyers.

As part of a broader strategy to claim that Flynn’s Covington team was incompetent, Sidney Powell claims (relying on Flynn’s declaration) that when the government made it clear to his lawyers they knew he had been lying, Flynn asked his lawyers “to make further inquiry with the SCO prosecutors about whether the FBI agents believed I had lied to them” (Flynn’s declaration is internally contradictory on this point, because he claims he heard rumors they didn’t believe this by November 30 but then, seven paragraphs later, he claims he never heard those rumors before he pled guilty on December 1). His attorney inquired and came back with the truthful response that the “agents stand by their statements.” Flynn claims that his attorneys did not tell him what he claims to be a critical detail, that the agents thought he sounded like he was telling the truth even though abundant other evidence (including Peter Strzok’s texts to Lisa Page, written before any draft 302s) make it clear they knew he was lying.

The information that counsel withheld concerned prior statements that the two FBI agents who interviewed Mr. Flynn in the White House had made about his “sure demeanor,” the lack of “indicators of deception,” and similar observations. Exs. Michael Flynn Declaration;Lori Flynn Declaration.

In an earlier round of briefing in this case, the government represented that it had communicated this information to the defendant on the day that the plea agreement was signed, November 30, 2017 [Gov’t’s Opp’n, ECF No. 122 at 16]. In its December 16, 2019 Opinion, moreover, this Court accepted and relied on that representation [Memorandum Opinion, ECF No. 144 at 32].As the Flynn Declarations demonstrate, however, that representation was mistaken: the government almost certainly made a disclosure to the defendant’s counsel on that day, but Covington did not then communicate the information to the defendant himself. Of course, in the vast majority of cases, communication to counsel is communication to the client, but it was not that day.

Flynn now claims it would have changed his mind to plead guilty if he learned that the FBI agents thought he was a pretty convincing liar, but his lawyers incompetently didn’t share that detail with him.

But wait.

There’s more.

Powell also suggests that the way the FBI investigated Flynn — first by monitoring how he responded to Trump’s first national security briefing (the one Flynn attended while secretly signing up to work for the Turkish government) and then by interviewing him in the White House — is proof they weren’t really investigating him.

Meanwhile, on January 24, 2017, as we have briefed elsewhere, FBI Director Comey and Deputy Director McCabe dispatched Agents Strzok and “SSA 1” to the White House— deliberately contrary to DOJ and FBI policy and protocols—without notifying DOJ.9

9 This was actually the FBI’s second surreptitious interview of Mr. Flynn—without informing him even so much as that he was the subject of their investigation. SSA 1 had “interviewed him” in a “sample Presidential Daily Briefing” (“PDB”) on August 17, 2016—unbeknownst to anyone outside the FBI or DOJ until revealed in the recent Inspector General Report of December 9, 2019.

This also goes to Mr. Flynn’s claim of actual innocence. Against the baseline interview the FBI surreptitiously obtained under the guise of the PDB (in August 2016), the agents conducted the White House interview and immediately reported back in three extensive briefings during which both agents assured the leadership of the DOJ and FBI they “saw no indications of deception,” and they believed so strongly that Mr. Flynn was shooting straight with them that Strzok pushed back against Lisa Page’s disbelief and Deputy Director McCabe’s cries of “bullshit.” ECF No. 133-2 at 4. This development is addressed in Flynn’s Motion to Dismiss for Egregious Government Misconduct filed contemporaneously herewith.

[snip]

The electronic communication written by SSA 1 arising from the presidential briefing was approved by Strzok. It was uploaded into Sentinel August 30, 2016. IG Report at 343 and n. 479. In truth, but unknown to Mr. Flynn until the release of this Report, SSA1 was actually there because he was investigating the candidate’s national security advisor as being “an agent of Russia.” This report of that interaction including purported statements by Mr. Flynn was put it in a sub-file of the Crossfire Hurricane file. That, and the DOJ document completely exonerating Mr. Flynn of that slanderous assertion, has never been produced to Mr. Flynn. This was extraordinary Brady and Giglio information that should have been provided to Mr. Flynn by Mr. Van Grack no later than upon entry of this Court’s Brady order

[snip]

With every disclosure and IG Report of the last eighteen months, it has become increasingly clear the FBI was not trying to learn facts from Mr. Flynn on January 24, 2017. Rather, the Agents were executing a well-planned, high-level trap that began at least as far back as August 15, 2016, when Strzok and Page texted about the “insurance policy” they discussed in McCabe’s office, opened the “investigation” on Mr. Flynn the next day, and inserted SSA 1 surreptitiously into the “sample PDB” the next day to investigate and assess Mr. Flynn.

Even if these assertions were true, none of it rebuts that Flynn told lies in that interview.

Which is probably why Powell goes on to argue that the answers that Flynn claims weren’t lies weren’t material to the FBI investigation, based in part on Judge Sullivan’s comments from the December 2018 sentencing hearing that probably were more indication that he wanted prosecutors to lay out how bad Flynn’s lies were.

Finally, the Court was not satisfied with the factual basis for the plea. It said it had “many, many, many questions.” Hr’g Tr. Dec. 18, 2018 at 20. The Court, sensing the materiality issues in the case, specifically left those questions open for another day. Id. at 50. 40

40 The element of materiality boils down to whether a misstatement “has a natural tendency to influence, or was capable of influencing, the decision of the decision-making body to which it was addressed.” United States v. Gaudin, 515 U.S. 506, 522-23 (1995). In applying this rule, courts analyze the statement that was made and the decision that the agency was considering. Universal Health Services, Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989, 2002-03 (2016). For a misstatement to be material, the agency must show that it would have made a different decision had the defendant told the truth.

The government alleges misstatements that were not material because the FBI agents did not come to the White House for a legitimate investigative purpose; they did not come to investigate an alleged crime. Instead, they came to get leverage over Mr. Flynn at a time when they felt the new administration was still disorganized. So they ignored policies and procedures. They went around the Department of Justice and the White House Counsel’s office, and they walked into the National Security Advisor’s office under false pretenses. They decided not to confront Mr. Flynn with any alleged misstatement not for a legitimate law enforcement purpose, but rather because they did not know if the effort to purge him from his office would be successful. If it was not, they wanted to maintain a collegial working relationship with him. If Mr. Flynn had answered the questions the way in which they imagine he should, nothing at all would have changed in the actions the FBI would have taken.

Powell, of course, presents no evidence for these wild claims. Moreover, she ignores the evidence of materiality that prosecutors submitted in their own sentencing memo.

The topic of sanctions went to the heart of the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation. Any effort to undermine those sanctions could have been evidence of links or coordination between the Trump Campaign and Russia.

She ignores, too, that prosecutors put her on notice that they’re going to show that Flynn continued to lack candor in his first meetings with Mueller’s team, a team that did not include either of the FBI agents she says had it in for her client.

Based on filings and assertions made by the defendant’s new counsel, the government anticipates that the defendant’s cooperation and candor with the government will be contested issues for the Court to consider at sentencing. Accordingly, the government will provide the defendant with the reports of his post-January 24, 2017 interviews. The government notes that the defendant had counsel present at all such interviews.

Flynn’s declaration actually accords with this. He describes how, after his first interview with Mueller’s prosecutors, “my attorneys told me that the first day’s proffer did not go well.” It wasn’t until several more meetings before Mueller’s team gave Flynn’s attorneys his first 302, which made it clear how dramatically he had lied.

All of which is to say that Powell’s most robust support for Flynn’s claim that he didn’t lie is that FBI agents believed he had lied well, which probably isn’t going to convince Sullivan to let him withdraw his sworn plea that he did in fact lie.

Cursory consideration of Cray

That makes it all the more problematic that Powell barely addresses what Judge Sullivan told both sides to: a hearing with sworn witnesses and to address US v Cray. True, she does say that if the government doesn’t agree with this motion Sullivan should maybe hold a hearing.

No hard and fast rule governs whether an evidentiary hearing is required before a court can properly adjudicate ineffective assistance of counsel claims, including those undergirding a motion to withdraw a guilty plea. Much depends on exactly what is being contested and what materials the court will have to consider in deciding the merits. In Taylor, 139 F.3d at 932-33, this Circuit wrote:

Ordinarily, when a defendant seeks to withdraw a guilty plea on the basis of ineffective assistance of trial counsel the district court should hold an evidentiary hearing to determine the merits of the defendant’s claims. . . . On the other hand, some claims of ineffective assistance of counsel can be resolved on the basis of the trial transcripts and pleadings alone.3

But she doesn’t commit to putting her client (and his former attorney) under oath, which is where this is heading.

And her briefing on Cray is cursory. She deals with the standard under which that defendant tried to withdraw his plea.

United States v. Cray, 47 F.3d 1203 (D.C. Cir. 1995), which this Court requested counsel address, denied withdrawal of a guilty plea because there was no violation of Rule 11. As more recent circuit decisions hold, Rule 11 violation is only one of the reasons that warrants granting a motion to withdraw a plea. Here, Sixth Amendment violations taint Mr. Flynn’s plea, and it cannot stand.38 United States v. McCoy, 215 F.3d 102, 107 (D.C. Cir. 2000) (“A plea based upon advice of counsel that ‘falls below the level of reasonable competence such that the defendant does not receive effective assistance’ is neither voluntary nor intelligent.”) (internal citation omitted).

Moreover, she claims there was a Rule 11 violation in the reallocution before Judge Sullivan, because he didn’t ask Flynn whether there were other promises to induce him to plead.

That plea colloquy did not, however, inquire into whether any undisclosed promises or threats induced the plea agreement. Moreover, the Court specifically expressed its dissatisfaction with the underlying facts supposedly supporting the factual basis for the plea. United States v. Cray, 47 F.3d 1203, 1207 (D.C. Cir. 1995) (“Where the defendant has shown his plea was taken in violation of Rule 11, we have never hesitated to correct the error.)”

But Judge Contreras did allocute to that (in addition to making Flynn attest that he was happy with the advice Rob Kelner gave him).

THE COURT: Have any threats or promises other than the promises made in the plea agreement been made to you to induce you to give up your right to the indictment?

THE DEFENDANT: No.

Flynn now claims that he pled to ensure Mueller would not prosecute his failson, but he didn’t raise it on December 1, 2017 when asked if there any more promises made to him.

Moreover, Powell does not address another part of Cray: that when the judge put him under oath, he revealed that his claims of innocence related to other charges, something Flynn is doing here.

Powell claims Covington did not give Flynn notice of their conflict but provides evidence they did

Rather than making a robust case that Flynn did not commit the crime that he pled guilty to, lying about Russia, she instead argues that Covington was fatally conflicted when they advised Flynn to plead guilty. She argues that Flynn told the entire truth to his Covington attorneys while they were preparing his FARA filing, they didn’t include the information he had provided them, and so they made him plead guilty to get out of trouble they had created themselves.

Before I explain the problems with this, recall that I raised questions about a conflict immediately after the December 2018 sentencing hearing. So I’m actually sympathetic to the argument.

But there are two problems with her argument.

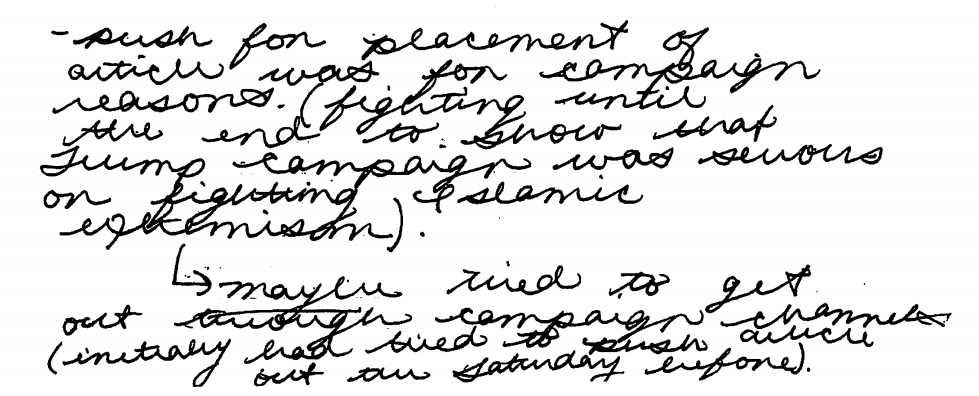

First, she’s obscuring the nature of the lies in Flynn’s FARA filing in an effort to pretend that Flynn did not lie to Covington when preparing the filing. I debunked some of her claims here, but one bears repeating. Flynn’s statement of offense described one of the false statements on the filing as “an op-ed by FLYNN published in The Hill on November 8, 2016 was written at his own initiative.” Powell pretends this is a dispute over whether Flynn actually wrote the op-ed himself. Flynn did tell Covington, truthfully, that Kian had drafted the op-ed, which Powell notes repeatedly.

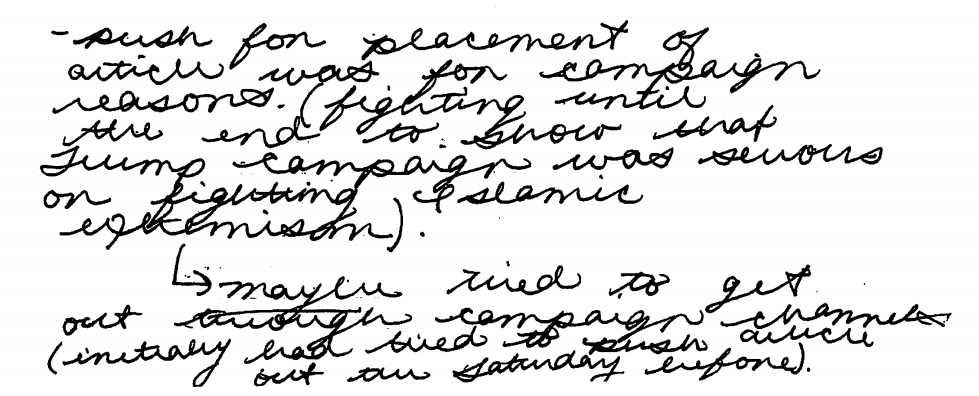

But Covington’s notes also show that Flynn told Covington the op-ed had nothing to do with the Turkish contract, and that he did it solely to prove that the Trump campaign was serious about fighting Islamic terrorism.

That is, he not only lied about whether it was his idea to write it, but lied about it being the deliverable for the Turkish contact altogether. As noted above, Flynn testified under oath he didn’t even know this op-ed was coming until Kian delivered it in full draft form to him. And, as DOJ has already made clear, Covington’s lawyers will testify that Flynn didn’t tell them the truth about the op-ed, as this interview report from Rob Kelner makes clear.

(U//FOUO) KELNER was informed by FLYNN the published 11/8/2016 Op-Ed article in The Hill was something he, FLYNN, had wanted to do out of his own interest. FLYNN wanted to show how Russia was attempting to create a wedge between Turkey and the United States. FLYNN informed KELNER the Op-Ed was not on behalf of FIG’s project with INOVO.

So the public record — including notes released by Powell — shows that Flynn (and Kian) were responsible for the false statements in the FARA filing, not Covington.

Moreover, documents submitted by Powell on Wednesday make it clear Covington informed Flynn of the conflict. Flynn (and his wife, who submitted a declaration that now makes it possible for prosecutors to breach spousal privilege) suggests he was only informed of the conflict twice — once in August and once in November after his first proffers. He describes the August advice as a 15-minute conversation he had after pulling over on the side of a road.

The call then occurred while we were driving to have dinner with some friends. It was an approximately 15-minute phone call, where we had pulled off to the side of a highway. They informed us that there was a development regarding a conflict of interest. They also mentioned the possibility of Bijan being indicted. Speaking to the conflict of interest, they stated that they were prepared to defend as vigorously, if the conflict became an issue. We told them we trusted them.

The government has, in the past, noted they raised a potential conflict with Covington twice, on November 1 and November 16, before they ever spoke with Flynn. An exhibit Powell included Wednesday shows that on November 20, 2017, Flynn responded to a Covington email stating the description of the conflict “is very clearly stated” but that “we’re good going forward with you all and very much trust that you will continue to guide us through this difficult time.” The email reflected at least three warnings from Covington:

- August 30, where they informed him of the conflict and suggested he “obtain advice from a lawyer independent of Covington”

- A later conversation where they suggested the name of another lawyer with expertise in legal ethics who had already determined he had no conflict who was “willing to be engaged by you for a reduced, fixed fee”

- The warning on November 19, which for the third time advised him to “seek advice from an independent lawyer about this”

Flynn did not contest their representation of those (at least) three warnings. Powell now claims they cited the wrong rule of professional conduct — about the only claim in the filing that might have merit. And — in a passage denying their (at least) third warning to Flynn — she also suggests that the Covington lawyers faced criminal liability themselves for repeating what their client told them.

What had begun as a simple mistake in doing the FARA filing suddenly had the potential of exposing the Covington lawyers to civil or criminal liability, significant headlines, and reputational risk. That the Covington lawyers thought that a “drive-by” cell-phone chat, while their client was on his way to dinner with his wife, was sufficient disclosure in these dire circumstances revealed their cavalier attitude and presaged far worse. [emphasis original]

She doesn’t note, of course, that Covington’s possible exposure on FARA, and the ability of the government to get them to testify, remained the same whether or not they remained Flynn’s lawyer.

And all that’s before Covington starts producing other records that are less complimentary to Flynn.

Remember: A key part of Sidney Powell’s argument here is that Covington — the lawyers who advised Flynn that if he withdrew his plea in December 2018 he’d only be giving Judge Sullivan more rope to hang himself with — provided obviously incompetent legal advice.

Be careful what you wish for

Way back when Flynn first got cute in advance of his December 2018 sentencing, I warned him, be careful what you wish for. Raising the circumstances of his FBI interview was likely, I predicted, to get Sullivan to ask for those details.

Which he subsequently did, resulting in damning new information about Flynn’s lies to be released.

I feel like that’s bound to happen here. For example, Powell keeps complaining that DOJ won’t provide her Flynn’s DIA briefings regarding his trips to Russia. She has raised what happened in Flynn’s proffers, but not provided the 302s which even Flynn’s declaration suggests was a disaster. The government has already telegraphed they may release this stuff.

There’s even the possibility that if Judge Sullivan asks to have witnesses, DOJ will ask that Don McGahn, John Eisenberg, or Reince Priebus testify. According to the Mueller Report, they all believed he was lying to them about what he remembered he had said to Kislyak.

So in addition to not heeding the advice about giving a judge more rope to hang you with, I feel like someone should have warned Flynn to be careful of what he wishes for. Again.

A number of people have pointed to Bill Barr’s sudden installation of a loyal aide at DC US Attorney and assumed it means the fix is in for the Flynn sentencing.

Attorney General William P. Barr on Thursday named former federal prosecutor Timothy Shea as the District’s interim U.S. attorney.

Shea, 59, currently serves as a counselor to Barr at the Justice Department. He will oversee the nation’s largest U.S. attorney’s office with 300 prosecutors.

The announcement comes just a day before Jessie K. Liu, the city’s current U.S. attorney, leaves office on Friday.

Liu, 47, has served in the post for a little over two years. President Trump on Jan. 6 nominated her to become the Treasury Department’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial crimes, and her nomination is pending before the Senate Banking Committee.

I absolutely don’t discount the possibility that Barr did this to better retaliate against Andrew McCabe and shut down the remaining investigations of Trump’s aides being conducted by the DC US Attorney’s office. As I may get around to showing, I think the risk is particularly acute for Roger Stone’s sentencing, where Trump has far more untapped exposure than Flynn. And it may well be the case that Barr and Shea force prosecutors to submit a half-hearted response to this motion to withdraw (though some of them are actually NSD attorneys who report up through other channels).

But at this point, the damage has already been done. There is no way to change the fact that Flynn has sworn to statements, under oath, before Judge Sullivan that materially conflict.