Last month’s squabble between Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz about USA Freedom Act led a number of USAF boosters to belatedly understand what I’ve been writing for years: that USAF expanded the universe of people whose records would be collected under the program, and would therefore expose more completely innocent people, along with more potential suspects, to the full analytical tradecraft of the NSA, indefinitely.

In an attempt to explain why that might be so, Julian Sanchez wrote this post, focusing on the limits on location data collection that restricted cell phone collection. Sanchez ignores two other likely factors — the probable inclusion of Internet phone calls and the ability to do certain kinds of connection chaining — that mark key new functionalities in the program which would have posed difficulties prior to USAF. But he also misses a lot of the public facts about location collection and cell phones under the Section 215 dragnet. This post will lay those out.

The short version is this: the FISC appears to have imposed some limits on prospective cell location collection under Section 215 even as the phone dragnet moved over to it, and it was not until August 2011 that NSA started collecting cell phone records — stripped of location — from AT&T under Section 215 collection rules. The NSA was clearly getting “domestic” records from cell phones prior to that point, though it’s possible they weren’t coming from Section 215 data. Indeed, the only known “successes” of the phone dragnet — Basaaly Moalin and Adis Medunjanin — identified cell phones. It’s not clear whether those came from EO 12333, secondary database information that didn’t include location, or something else.

Here’s the more detailed explanation, along with a timeline of key dates:

There is significant circumstantial evidence that by February 17, 2006 — two months before the FISA Court approved the use of Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act to aspire to collect all Americans’ phone records — the FISA Court required briefing on the use of “hybrid” requests to get real-time location data from targets using a FISA Pen Register together with a Section 215 order. The move appears to have been a reaction to a series of magistrates’ rulings against a parallel practice in criminal cases. The briefing order came in advance of the 2006 PATRIOT Act reauthorization going into effect, which newly limited Section 215 requests to things that could be obtained with a grand jury subpoena. Because some courts had required more than a subpoena to obtain location, it appears, FISC reviewed the practice in the FISC — and, given the BR/PR numbers reported in IG Reports, ended, sometime before the end of 2006 though not immediately.

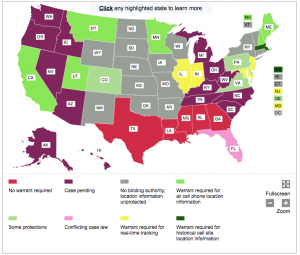

The FISC taking notice of criminal rulings and restricting FISC-authorized collection accordingly would be consistent with information provided in response to a January 2014 Ron Wyden query about what standards the FBI uses for obtaining location data under FISA. To get historic data (at least according to the letter), FBI used a 215 order at that point. But because some district courts (this was written in 2014, before some states and circuits had weighed in on prospective location collection, not to mention the 11th circuit ruling on historical location data under US v. Davis) require a warrant, “the FBI elects to seek prospective CSLI pursuant to a full content FISA order, thus matching the higher standard imposed in some U.S. districts.” In other words, as soon as some criminal courts started requiring a warrant, FISC apparently adopted that standard. If FISC continued to adopt criminal precedents, then at least after the first US v. Davis ruling, it would have and might still require a warrant (that is, an individualized FISA order) even for historical cell location data (though Davis did not apply to Stingrays).

FISC doesn’t always adopt the criminal court standard; at least until 2009 and by all appearances still, for example, FISC permits the collection, then minimization, of Post Cut Through Dialed Digits collected using FISA Pen Registers, whereas in the criminal context FBI does not collect PCTDD. But the FISC does take notice of, and respond to — even imposing a higher national security standard than what exists at some district levels — criminal court decisions. So the developments affecting location collection in magistrate, district, and circuit courts would be one limit on the government’s ability to collect location under FISA.

That wouldn’t necessarily prevent NSA from collecting cell records using a Section 215 order, at least until the Davis decision. After all, does that count as historic (a daily collection of records each day) or prospective (the approval to collect data going forward in 90 day approvals)? Plus, given the PCTDD and some other later FISA decisions, it’s possible FISC would have permitted the government to collect but minimize location data. But the decisions in criminal courts likely gave FISC pause, especially considering the magnitude of the production.

Then there’s the chaos of the program up to 2009.

At least between January 2008 and March 2009, and to some degree for the entire period preceding the 2009 clean-up of the phone and Internet dragnets, the NSA was applying EO 12333 standards to FISC-authorized metadata collection. In January 2008, NSA co-mingled 215 and EO 12333 data in either a repository or interface, and when the shit started hitting the fan the next year, analysts were instructed to distinguish the two authorities by date (which would have been useless to do). Not long after this data was co-mingled in 2008, FISC first approved IMEI and IMSI as identifiers for use in Section 215 chaining. In other words, any restrictions on cell collection in this period may have been meaningless, because NSA wasn’t heeding FISC’s restrictions on PATRIOT authorized collection, nor could it distinguish between the data it got under EO 12333 and Section 215.

Few people seem to get this point, but at least during 2008, and probably during the entire period leading up to 2009, there was no appreciable analytical border between where the EO 12333 phone dragnet ended and the Section 215 one began.

There’s no unredacted evidence (aside from the IMEI/IMSI permission) the NSA was collecting cell phone records under Section 215 before the 2009 process, though in 2009, both Sprint and Verizon (even AT&T, though to a much less significant level) had to separate out their entirely foreign collection from their domestic, meaning they were turning over data subject to EO 12333 and Section 215 together for years. That’s also roughly the point when NSA moved toward XML coding of data on intake, clearly identifying where and under what authority it obtained the data. Thus, it’s only from that point forward where (at least according to what we know) the data collected under Section 215 would clearly have adhered to any restrictions imposed on location.

In 2010, the NSA first started experimenting with smaller collections of records including location data at a time when Verizon Wireless was named on primary orders. And we have two separate documents describing what NSA considered its first collection of cell data under Section 215 on August 29, 2011. But it did so only after AT&T had stripped the location data from the records.

It appears Verizon never did the same (indeed, Verizon objected to any request to do so in testimony leading up to USAF’s passage). The telecoms used different methods of delivering call records under the program. In fact, in August 2, 2012, NSA’s IG described the orders as requiring telecoms to produce “certain call detail records (CDRs) or telephony metadata,” which may differentiate records that (which may just be AT&T) got processed before turning over. Also in 2009, part of Verizon ended its contract with the FBI to provide special compliance with NSLs. Both things may have affected Verizon’s ability or willingness to custom what it was delivering to NSA, as compared to AT&T.

All of which suggests that at least Verizon could not or chose not to do what AT&T did: strip location data from its call records. Section 215, before USAF, could only require providers to turn over records they kept, it could not require, as USAF may, provision of records under the form required by the government. Additionally, under Section 215, providers did not get compensated after the first two dragnet orders.

All that said, the dragnet has identified cell phones! In fact, the only known “successes” under Section 215 — the discovery of Basaaly Moalin’s T-Mobile cell phone and the discovery of Adis Medunjanin’s unknown, but believed to be Verizon, cell phone — did, and they are cell phones from companies that didn’t turn over records. In addition, there’s another case, cited in a 2009 Robert Mueller declaration preceding the Medunjanin discovery, that found a US-based cell phone.

There are several possible explanations for that. The first is that these phones were identified based off calls from landlines and/or off backbone records (so the phone number would be identified, but not the cell information). But note that, in the Moalin case, there are no known land lines involved in the presumed chain from Ayro to Moalin.

Another possibility — a very real possibility with some of these — is that the underlying records weren’t collected under Section 215 at all, but were instead collected under EO 12333 (though Moalin’s phone was identified before Michael Mukasey signed off on procedures permitting the chaining through US person records). That’s all the more likely given that all the known hits were collected before the point in 2009 when the FISC started requiring providers to separate out foreign (EO 12333) collection from domestic and international (Section 215) collection. In other words, the Section 215 phone dragnet may have been working swimmingly up until 2009 because NSA was breaking the rules, but as soon as it started abiding by the rules — and adhering to FISC’s increasingly strict limits on cell location data — it all of a sudden became virtually useless given the likelihood that potential terrorism targets would use exclusively cell and/or Internet calls just as they came to bypass telephony lines. Though as that happened, the permissions on tracking US persons via records collected under EO 12333, including doing location analysis, grew far more permissive.

In any case, at least in recent years, it’s clear that by giving notice and adjusting policy to match districts, the FISC and FBI made it very difficult to collect prospective location records under FISA, and therefore absent some means of forcing telecoms to strip their records before turning them over, to collect cell data.

Read more →