“Not Us at All:” In His Bid to Pierce Privilege, John Durham Makes Strong Case for Immunizing Rodney Joffe

The folks in John Durham’s Office of Conspiracy-Mongering seem to be frazzled. What other explanation might they have for a positively hysterical entry in their bid to pierce Democrats’ privilege claims?

To be clear (because frothy lawyers are making false claims about what I think might happen), I think some of the privilege claims being made are suspect. Durham might succeed, in part, and a more professional effort to do so in a different case — say, Igor Danchenko’s — might get the results he wanted.

But last night’s filing, even ignoring that Durham released confidential emails while purportedly asking permission to release them under seal, was a clown show.

Start with what Durham doesn’t mention.

In Michael Sussmann’s opposition to Durham’s motion to compel, he raised four procedural problems with Durham’s effort.

First, the Special Counsel’s Motion is untimely. Despite knowing for months, and in some cases for at least a year, that the non-parties were withholding material as privileged, he chose to file this Motion barely a month before trial—long after the grand jury returned an Indictment and after Court-ordered discovery deadlines had come and gone.

Second, the Special Counsel’s Motion should have been brought before the Chief Judge of the District Court during the pendency of the grand jury investigation, as the rules of this District and precedent make clear.

Third, the Special Counsel has seemingly abused the grand jury in order to obtain the documents redacted for privilege that he now challenges. He has admitted to using grand jury subpoenas to obtain these documents for use at Mr. Sussmann’s trial, even though Mr. Sussmann had been indicted at the time he issued the grand jury subpoenas and even though the law flatly forbids prosecutors from using grand jury subpoenas to obtain trial discovery. The proper remedy for such abuse of the grand jury is suppression of the documents.

Fourth, the Special Counsel seeks documents that are irrelevant on their face. Such documents do not bear on the narrow charge in this case, and vitiating privilege for the purpose of admitting these irrelevant documents would materially impair Mr. Sussmann’s ability to prepare for his trial.

While Durham makes unconvincing attempts to address the first and fourth issue (to which I’ll return), he doesn’t meaningfully address the second and third. In this post, I opined that the third — his blatant abuse of grand jury rules — could be easily addressed (which he didn’t try to do), but given how obviously irrelevant and potentially inadmissible these documents are to the charge against Sussmann, I’m not so sure anymore.

But Durham only addresses Sussmann’s argument that he ignored local rules and deliberately bypassed Beryl Howell, who would have been the proper person to assess these privilege claims, by making unconvincing claims he made a good faith effort to do so directly.

There’s another thing he doesn’t mention, another point Sussmann raised. Some of the emails Durham is focused on make it explicit that there was a separation between Fusion’s research (including the Steele dossier) and the DNS research.

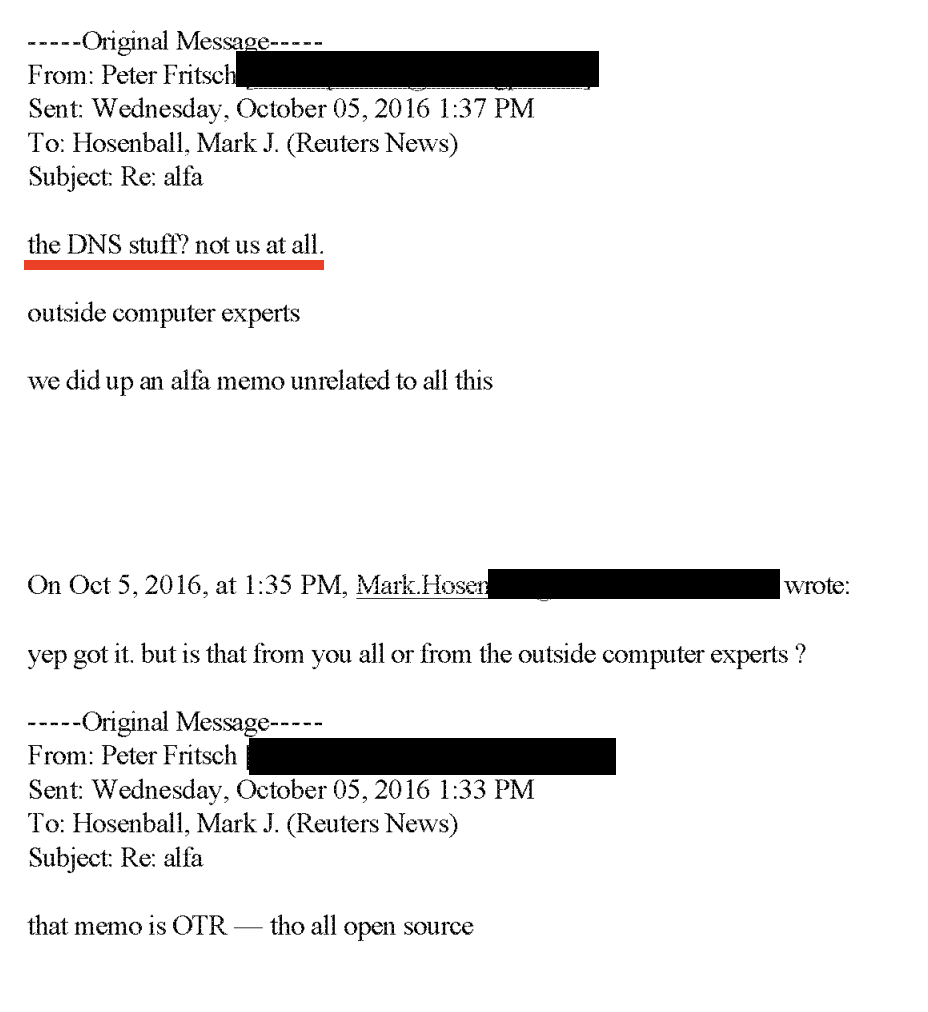

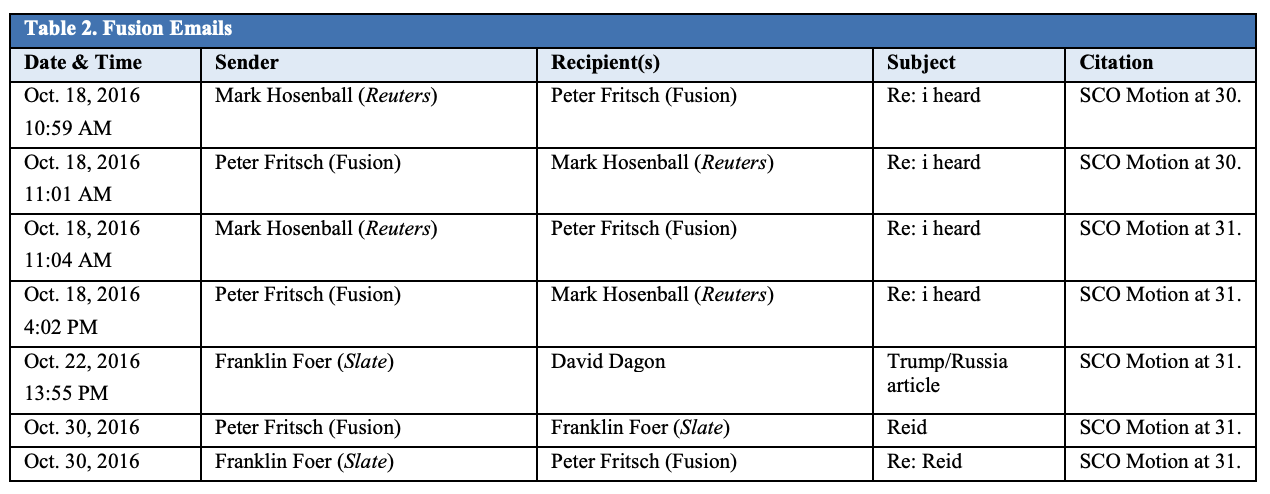

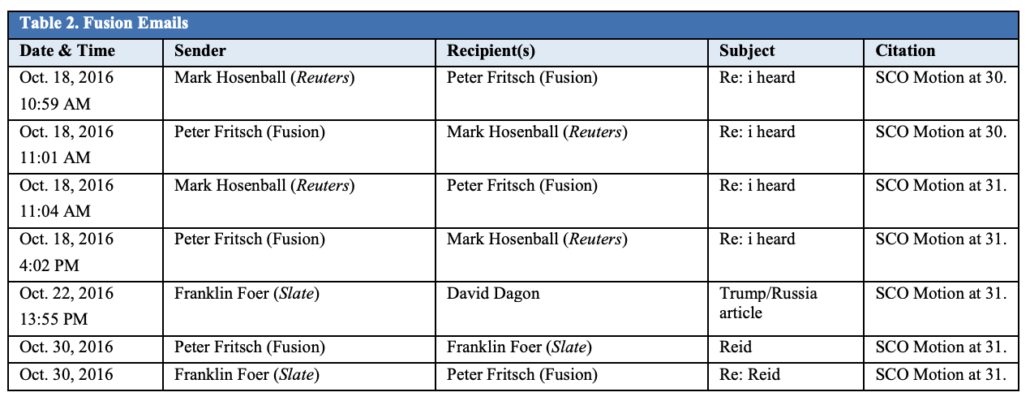

The Special Counsel makes much of the fact that (1) there was an August 11, 2016 email exchange between Mr. Sussmann, Mr. Elias, and Fusion employees with the subject “connecting you all by email” and (2) that thereafter, Fusion employees “began to exchange drafts of a document . . . the defendant would provide to the FBI General Counsel.” Motion ¶¶ 29, 30. But in seeking to draw inflammatory and unsupported inferences, the Special Counsel ignores another email—that he produced in discovery—in which a Fusion employee stated that the document was “an [A]lfa memo unrelated to all [the Alfa Bank DNS information].” See Email from P. Fritsch to M. Hosenball (Oct. 5, 2016), SC-00027475, at SC-00027476.

Indeed, Peter Fritsch told Mark Hosenball that “the DNS stuff” was “not us at all.”

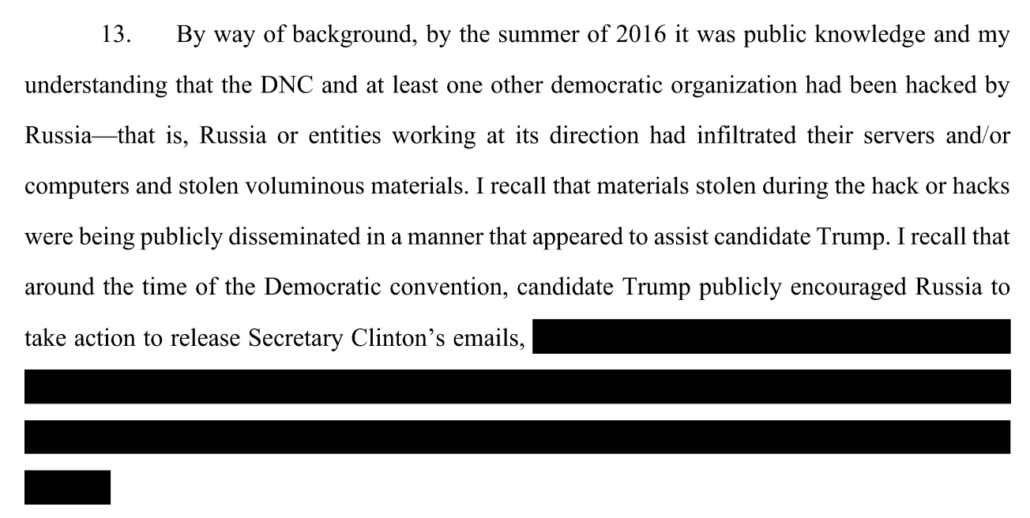

Even though Sussmann pointed that out, Durham did not address the clear evidence in his possession that this was not a joint effort. Other of these communications, Peter Fritsch has testified under oath, he engaged in because he was independently alarmed about the Alfa Bank allegations. And some of them, Fusion has noted before, derived from Paul Singer’s involvement in the project and Singer didn’t invoke privilege.

Much of rest, though, is primarily focused on Carter Page and Sergei Millian (though in one place, Durham also downplays that Fusion was investigating Felix Sater, which is interesting given Durham’s efforts to pretend the notion Trump had multiple back channels with Russia is malicious and political). Indeed, included emails explain that what had been a potentially scandalous reference — the allegation that Millian had an email “with” Alfa Bank — actually came from public Internet research, not from the DNS analysis.

Given the focus on Millian, though, it is inexplicable why Durham is trying to pierce these privilege claims here rather than in the case where it might matter, Danchenko’s. Rather, I can think of some explanations, such as that someone in Millian’s organization viewed the obligation to register under FARA as a “problem” as early as 2013, but none of them are legally sound.

The far more interesting aspect of Durham’s filing comes in how he addresses two substantive issues. First, here’s how he addressed the timing of his belated decision to try to pierce privilege.

As an initial matter, the defendant and others accuse the Government of carrying out an untimely “full frontal assault” on the attorney client privilege by raising these issues more than a month before trial. (Def. Opp. at 1.) But those characterizations distort reality. Indeed, the opposite is true: the primary reason the Government waited until recently to bring these issues to the Court’s attention was because it wanted to carefully pursue and exhaust all collaborative avenues of resolving these matters short of litigation. The Government did so to avoid bringing a challenge to the parties’ privilege determinations and to ensure that it first gathered all relevant facts and provided the relevant privilege holders with notice and an opportunity to explain the bases for their privilege assertions. Even the emails between the Government and counsel that the defendant quotes in his opposition reflect this very purpose. See., e.g., Def. Opp. at 7 (quoting emails in which the Special Counsel’s Office stated that it “wanted to give all parties involved the opportunity to weigh in before we. . . seek relief from the Court” and requested a call “to avoid filing motions with the Court.”).

In addition, over the course of months, and until recently, the Government has been receiving voluminous rolling productions of documents and privilege logs from numerous parties. The Government carefully analyzed such productions in order assess and re-assess the potential legal theories that might support the parties’ various privilege assertions. In connection with that process, the Special Counsel’s Office reached out to each of those parties’ counsel numerous times, directing their attention to specific documents where possible and communicating over email and phone in an effort to obtain non-privileged explanations for the relevant privilege determinations.2 The Government also supplied multiple counsel with relevant caselaw and pointed them to documents and information in the public domain that it believed bore on these issues. The Government was transparent at every step of these discussions in stating that it was contemplating seeking the Court’s intervention and guidance. Unfortunately, despite the Government’s best efforts and numerous phone calls, it was not able to obtain meaningful, substantive explanations to support these continuing broad assertions of privilege and/or work product protections. [my emphasis]

This flips a point Sussmann made on its head — that Durham kept prodding Sussmann to waive privilege. “[T]he Special Counsel has been asking Mr. Sussmann whether there would be any waiver of privilege in this case because of his concern that a privilege waiver at this stage in the proceedings would fundamentally impact the course of trial.”

Durham provides no dates on his claimed efforts to resolve the privilege issues. But Sussmann has already revealed what some of those dates are. The two Durham cites were in August.

Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Patrick Stokes, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, et al. (Aug. 9, 2021) (requesting a call to discuss privilege issues with a hope “to avoid filing motions with the Court”); Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Patrick Stokes, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, et al. (Aug. 14, 2021) (stating that the Special Counsel “wanted to give all parties involved the opportunity to weigh in before we . . . pursue particular legal process, or seek relief from the Court”). And since January— before the deadline to produce unclassified discovery had passed—the Special Counsel suggested that such a filing was imminent, telling the DNC, for example, that he was “contemplating a public court filing in the near term.” Email from Andrew DeFilippis, Dep’t of Just., to Shawn Crowley, Kaplan Hecker & Fink LLP (Jan. 17, 2022).

2 In response to these inquiries and discussions, Tech Executive-1’s counsel withdrew his client’s privilege assertions over a small number of documents, and Fusion GPS produced a redacted version of its retention agreement with Perkins Coie. [my emphasis]

August is when Durham should have been involving Chief Judge Howell. Instead, we’re in April, and Durham is only now involving Judge Christopher Cooper. Importantly, using the dates Sussmann decided to include but which Durham did not, Durham was talking about taking imminent action in January, over two months before he first raised piercing privilege. After that, Durham again nudged Sussmann to waive privilege on his own. And the only reason why Durham was still getting responses to subpoenas, to the extent he was, is because he subpoenaed some of this after indicting (again, which he doesn’t address).

Given Durham’s claims he was trying to use other methods to get this information, his explanation of why he “only recently” decided he needed to pierce privilege is utterly damning: He only recently decided he needed to immunize Laura Seago and call her as a witness, he says.

It was only recently, when the Government determined it would need to call an employee of Fusion GPS as a trial witness (the “Fusion Witness”), that the Government concluded these issues could not be resolved without the Court’s attention. Because all or nearly all of the Fusion Witness’s expected testimony on these matters concern work carried out under an arrangement that the privilege holders now contend was established for the purpose of providing legal advice, it is essential to resolve the parties’ potential disputes about the appropriate bounds of such testimony (and the redaction or withholding of related documents).

That’s utterly damning because one of the last two things Alfa Bank was pursuing in their John Doe lawsuits before they were sanctioned, on Thursday, February 10, was to revisit privilege claims made by Fusion in a September Seago deposition with Alfa Bank (Seago’s first interview, in March 2021, was abandoned quickly). The reason Alfa gave for needing to challenge privilege claims Seago made in a 4-hour September deposition at which she invoked privilege over 60 times was because, “people at Fusion are speaking with the likes of Rodney Joffe.” And before Associate Judge Heidi Pasachow could rule, Alfa Bank was sanctioned to prevent it from helping Russia to attack democracy.

As I’ve laid out, all of Durham’s missed deadlines came after he could no longer rely on Alfa Bank to do his dirty work. As did, by his own description, the belated decision that he needs to immunize Seago and get her to testify at trial.

And that’s important because in spite of the pages and pages of irrelevant emails, when Durham turns to make the case that he needs to pierce this privilege, he again turns to Seago, claiming that she has “unique” knowledge about the charges against Sussmann.

Where a party seeks to overcome work product protection, it must show either that “it has a substantial need for the materials to prepare its case and cannot, without undue hardship obtain their substantial equivalent by other means” for fact work product, or make an “extraordinary showing of necessity” to obtain opinion work product. Boehringer, 778 F.3d at 153 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (quotations omitted).

Here, the vast majority of the relevant materials likely constitute fact work product, given that few of the communications involve an attorney. In addition, the Government has met both prongs of the relevant test. First, the Government has a “substantial need” for materials that it has requested the Court to review in camera. Those materials include, for example, communications between Tech Executive-1 and the Fusion Witness whom the Government will call at trial. The Fusion Witness is, to the Government’s knowledge, the only Fusion GPS employee who exchanged emails with Tech Executive-1 concerning the Russian Bank-1 allegations (or any other issue). The Fusion Witness also (i) acted as the firm’s primary “technical” expert; (ii) worked for an extended time period on issues relating to the Russian Bank-1 allegations; (iii) was a part of the team that handled work under Fusion’s contract with HFA and the DNC; and (iv) met in 2016 with various parties – including Law Firm-1, Tech Executive-1, and the media – about the Russian Bank-1 allegations. As such, the Fusion Witness undoubtedly possesses unique insight to the core issue to be decided by the jury—i.e., whether the defendant was acting on behalf of one or more clients when he worked on the Russian Bank-1 allegations. Accordingly, the Government has a “substantial need” to obtain the Fusion Witness’s communications relating to the Russian Bank-1 allegations. Moreover, the materials for which the Government has requested in camera review also include internal Fusion GPS communications regarding one of the three white papers that the defendant provided to the FBI, namely, the “[Russian Bank-1’s parent company] Overview” paper. Communications regarding the origins and background the very Fusion GPS paper that the defendant brought to the FBI are therefore likely to shed unique light on the defendant’s meeting with the FBI General Counsel, including the defendant’s work on behalf of his clients. Fusion GPS’s communications regarding that paper in the days prior to the defendant’s meeting with the FBI General Counsel are also likely to reveal information about the paper’s intended purpose and audience. Such facts will, again, shed critical light on the defendant’s conduct and meeting with the FBI.

Second, the Government cannot “without undue hardship obtain the[] substantial equivalent” of these materials “by other means.” Boehringer Ingelheim Pharms., Inc., 778 F.3d at 153. That is because these materials constitute mostly internal Fusion GPS communications and, accordingly, are not available from any other source. To the extent these communications reflect emails with Tech Executive-1, they are similarly unavailable because Tech Executive-1 has invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Therefore, obtaining the materials or their substantial equivalent from another source would not merely present an “undue hardship,” but rather, is impossible. [my emphasis]

This is a fairly astonishing argument.

That’s because Seago’s knowledge of the communications she had with Joffe is not unique. Joffe also has knowledge of their communications. To get Seago’s testimony, Durham plans to immunize her.

Yet he says he can’t get the very same testimony from Joffe because Joffe would invoke the Fifth.

Durham has an obvious alternative, and it just so happens to be the alternative that Sussmann is also seeking: To immunize not Seago, but Joffe. That would be more beneficial for Durham, if he really wants that testimony, because Joffe can waive privilege over precisely these communications and enter them as evidence with no hearsay exception. Immunizing Joffe gives Durham everything he wants and his testimony would be unquestionably pertinent to the charge against Sussmann.

Just twelve days ago, John Durham argued that he’s not playing fast-and-loose with his immunity decisions and that Joffe would offer no testimony useful to Sussmann (though to do so, Durham misrepresented Sussmann’s statement about Joffe’s role in helping to kill the NYT story).

Indeed, to now arbitrarily force the Government to immunize Tech Executive-1 merely because the defense believes he would offer arguably helpful testimony to the defendant would run afoul of the law and inject the Court into matters plainly reserved to the Executive Branch.

[snip]

(The Government also currently intends to seek immunity at trial for an individual who was employed at the U.S. Investigative Firm. But unlike Tech Executive-1, that individual is considered a “witness” and not a “subject” of the Government’s investigation based on currently-known facts.)

Finally, the defendant fails to plausibly allege – nor could he – that the Government here has “deliberately denied immunity for the purpose of withholding exculpatory evidence and gaining a tactical advantage through such manipulation.” Ebbers, 458 F. 3d at 119 (internal citation and quotations omitted). The defendant’s motion proffers that Tech Executive-1 would offer exculpatory testimony regarding his attorney-client relationship with the defendant, including that Tech Executive-1 agreed that the defendant should convey the Russian Bank-1 allegations to help the government, not to “benefit” Tech Executive-1. But that testimony would – if true – arguably contradict and potentially incriminate the defendant based on his sworn testimony to Congress in December 2017, in which he expressly stated that he provided the allegations to the FBI on behalf of an un-named client (namely, Tech Executive-1). And in any event, even if the defendant and his client did not seek specifically to “benefit” Tech Executive-1 through his actions, that still would not render his statement to the FBI General Counsel true. Regardless of who benefited or might have benefited from the defendant’s meeting, the fact still remains that the defendant conducted that meeting on behalf of (i) Tech Executive-1 (who assembled the allegations and requested that the defendant disseminate them) and (ii) the Clinton Campaign (which the defendant billed for some or all of his work). The proffered testimony is therefore not exculpatory, and certainly not sufficiently exculpatory to render the Government’s decision not to seek immunity for Tech Executive-1 misconduct or an abuse.6

6 The defendant’s further proffer that Tech Executive-1 would testify that (i) the defendant contacted Tech Executive-1 about sharing the name of a newspaper with the FBI General Counsel, (ii) Tech Executive-1 and his associates believed in good faith the Russian Bank-1 allegations, and (iii) Tech Executive-1 was not acting at the direction of the Clinton Campaign, are far from exculpatory. Indeed, even assuming that all of those things were true, the defendant still would have materially misled the FBI in stating that he was not acting on behalf of any client when, in fact, he was acting at Tech Executive-1’s direction and billing the Clinton Campaign.

Now, he’s claiming that the only possible way he can get testimony pertaining to Seago’s communications with Joffe is to immunize Seago and breach both Joffe’s and the Democrats’ claims of privilege.

By far the easiest way of solving this issue — and the one that meets Sussmann’s due process rights — is instead to immunize Joffe.

It’s a great case Durham made that they should cede to Sussmann’s request and immunize Joffe!

We’ll see what Cooper thinks of these claims at the status hearing tomorrow (because the hearing is in person, it’s unclear whether I’ll be able to call in).

But what is clear is that Durham keeps presenting evidence that he’s looking in the wrong place for the evidence he says he needs.