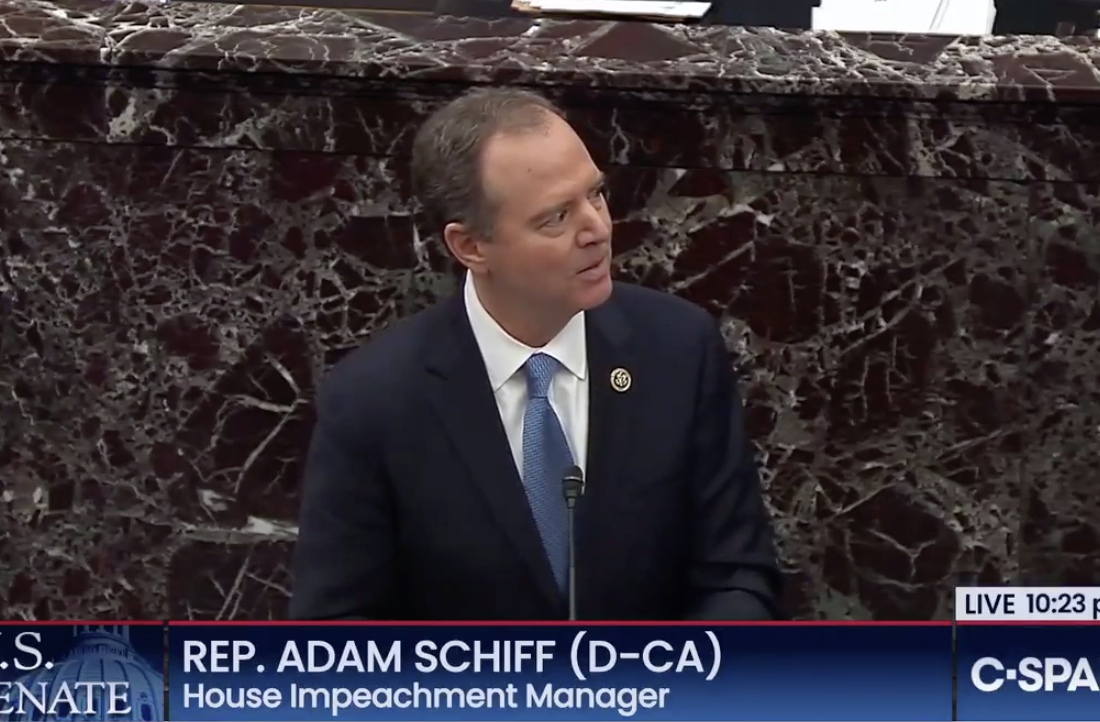

Something happened in a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing earlier this month that is interesting background to some of the details about the Mueller Investigation that have come out of late.

The guy who oversaw the Mueller Report appears unfamiliar with the Mueller Report

In the hearing, Dick Durbin tried to get Rod Rosenstein to defend the investigation he had overseen. Early on in the exchange, Rosenstein claimed that,

I do not consider the investigation to be corrupt, Senator, but I certainly understand, I understand the President’s frustration given the outcome, which was in fact that there was no evidence of conspiracy between Trump campaign advisors and Russians.

That’s of course not what the Report said at all. Rather, it said that,

[T]he investigation did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.

[snip]

A statement that the investigation did not establish particular facts does not mean there was no evidence of those facts.

Had Durbin been prepared for this answer, he might have invited Rosenstein to quote where the Report says that there was no evidence of conspiracy, which he would have been unable to do. Instead, Durbin asked Rosenstein whether he agreed with several other things that (he claimed) the report said:

- The Russian government perceived it would benefit from a Trump presidency and worked to secure that outcome

- There were more than 120 contacts between the Trump campaign and individuals linked to Russia

- The Trump campaign “knew about, welcomed, and expected to benefit electorally from Russia’s interference”

- The Trump campaign planned a messaging strategy around the WikiLeaks releases

In response to the first, Rosenstein claimed he didn’t know what the government (of Russia, apparently) was thinking, but could only say what their conduct was. To the second, Rosenstein said he had no reason to dispute the finding, though did not acknowledge directly that that’s what the report said.

In response to the third, Rosenstein asked Durbin what page he was referring to. Durbin claimed, incorrectly, it appeared on pages 1 to 2. Rosenstein made a great show of paging through the report, seemingly reading the passage in question, and said, “I’m not sure whether you were quoting from the Report or not Senator, but I have it in front of me … I apologize sir, I’m not seeing those words in the report if you could direct me to where it is in the report.”

In response to the fourth assertion, Rosenstein noted that that specific point says, “according to Mr. Gates, that’s attributed to Mr. Gates, I don’t think that’s a finding of the, Mueller, it’s what one of the … witnesses said.”

To be fair to Rosenstein, the exact words Durbin read do not appear in the report, just as “there was no evidence of conspiracy” does not appear in the report. Just the phrase, “the Campaign expected it would benefit electorally from information stolen and released through Russian efforts,” appears on pages 1 and 2 — though even that, Rosenstein was too cowardly to acknowledge. But unlike Rosenstein’s claim that the report showed no evidence of conspiracy, the rest of Durbin’s statement is backed by the report. On page 5, for example, the report explains that Trump showed interest in and welcomed the releases.

The presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump (“Trump Campaign” or “Campaign”) showed interest in WikiLeaks’s releases of documents and welcomed their potential to damage candidate Clinton.

And as for only Rick Gates describing a focused campaign effort to prepare for the WikiLeaks release, other witnesses, including campaign manager Paul Manafort, described similar obsession with the emails. At least five different witnesses gave testimony consistent with Gates’, and not all the people involved in such discussions were quoted in the Mueller Report.

Given Mueller’s own need to refer to the report and strict adherence to the specific language in the report when he testified before Congress, I can’t complain that Rosenstein seemed even less familiar with the contents of the report than Mueller (and elsewhere Rosenstein confessed he was uncertain about other key details). But my big takeaway from his testimony — aside from the fact that he seems intent on saying what Bill Barr, Donald Trump, and Lindsey Graham want him to say, whether or not it accords with reality — is that he exhibited none of the familiarity with the report I expected he would have.

It seems an important lesson. Rod Rosenstein, with no apparent familiarity with the report’s actual content, instead adopted the false lines that Trump and Barr have about the investigation, incorporating the ones on Barr’s four-page memo misrepresenting the findings, including where the memo neglected to provide the lead-up to the quotation that, “the investigation did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.”

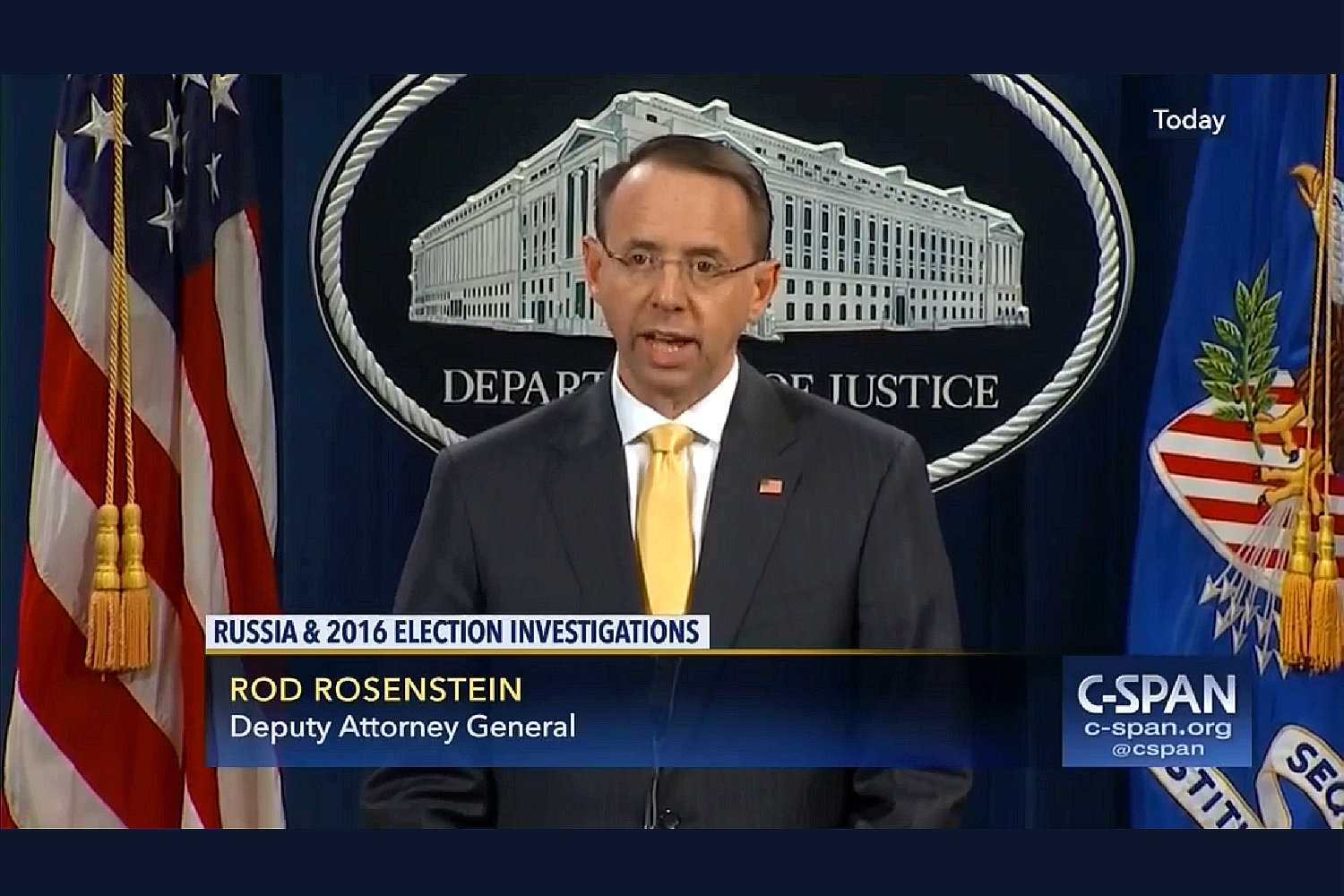

Ed O’Callaghan (and Steve Engel) wrote Barr’s declination, not Rosenstein

That’s one reason I think the memo that Steven Engel and Ed O’Callaghan wrote Billy Barr on March 24, 2019 recommending he decline to prosecute the President is probably the most interesting Mueller-related release from Friday. In actuality, DOJ released just the first and last page of the memo, and redacted all the justifications. But the first page shows that Engel — who as OLC head should have absolutely zero input into the specifics of a criminal declination, particularly regarding a report that presumed OLC had ruled out such prosecutions categorically — and O’Callaghan wrote the actual declination of Trump. The memo only went “through” Rosenstein (though Rosenstein definitely initialed it).

About half that first page is redacted, but not a footnote that says,

Given the length and detail of the Special Counsel’s Report, we do not recount the relevant facts here. Our discussion and analysis assumes familiarity with the Report as well as much of the background surrounding the Special Counsel’s investigation.

I have every reason to believe that O’Callaghan, unlike Rosenstein, is reasonably familiar with the workings of the Mueller Report (but Rosenstein must have gotten his misunderstandings of what it showed from O’Callaghan).

But whatever logic is laid out in that memo, the discussion apparently does not tie closely to the actual facts.

That means both Barr and Rosenstein could well have approved it without any familiarity with the actual facts.

In spite of Rosenstein’s ignorance, DOJ had to read about Roger Stone’s cover-up closely to redact it

Rosenstein’s professed lack of familiarity with Trump’s enthusiasm to exploit the WikiLeaks release is interesting given how important it had to have been in March 2019, when Mueller was publishing his conclusions. That’s because it was the one ongoing proceeding treated as such in the report release. So a great deal of the report got redacted — properly — in the interest of protecting Roger Stone’s right to a fair trial. Someone at DOJ — and the process may have been overseen by O’Callaghan — had to have read the Stone details closely if only to make sure none of the rest of us could.

That said, even before DOJ released the report, it was immediately clear how inconsistent the Stone findings were with Billy Barr’s public statements. Barr’s categorical comments about conspiracy pertained only to conspiring directly with Russia, which allowed him to make assertions that completely ignored Stone’s attempts — via means that have not yet been made public — to optimize the WikiLeaks releases.

On Friday, all the things that Barr was covering up became public in one narrative.

There was very little that had not been previously published in Friday’s release of the report. The details in the report showed up in Stone’s prosecution, the trial, and the warrants released in April. But the description of how many witnesses knew of Trump and Stone’s focus on the releases — including those like Paul Manafort and Steve Bannon who always tried to protect Trump in their testimony — sure does make Rosenstein’s denials look deliberate.

In debriefings with the Office, former deputy campaign chairman Rick Gates said that, before Assange’s June 12 announcement, Gates and Stone had a phone conversation in which Stone said something “big” was coming and had to do with a leak of information.195 Stone also said to Gates that he thought Assange had Clinton emails. Gates asked Stone when the information was going to be released. Stone said the release would happen very soon. According to Gates, between June 12, 2016 and July 22, 2016, Stone repeated that information was coming. Manafort and Gates both called to ask Stone when the release would happen, and Gates recalled candidate Trump being generally frustrated that the Clinton emails had not been found.196

Paul Manafort, who would later become campaign chairman, provided similar information about the timing of Stone’s statements about WikiLeaks.197 According to Manafort, sometime in June 2016, Stone told Manafort that he was dealing with someone who was in contact with WikiLeaks and believed that there would be an imminent release of emails by WikiLeaks.19

Michael Cohen, former executive vice president of the Trump Organization and special counsel to Donald J. Trump,199 told the Office that he recalled an incident in which he was in candidate Trump’s office in Trump Tower when Stone called. Cohen believed the call occurred before July 22, 2016, when WikiLeaks released its first tranche of Russian-stolen DNC emails.200 Stone was patched through to the office and placed on speakerphone. Stone then told the candidate that he had just gotten off the phone with Julian Assange and in a couple of days WikiLeaks would release information. According to Cohen, Stone claimed that he did not know what the content of the materials was and that Trump responded, “oh good, alright” but did not display any further reaction.201 Cohen further told the Office that, after WikiLeaks’s subsequent release of stolen DNC emails in July 2016, candidate Trump said to Cohen something to the effect of, “I guess Roger was right.”202

After WikiLeaks’s July 22, 2016 release of documents, Stone participated in a conference call with Manafort and Gates. According to Gates, Manafort expressed excitement about the release and congratulated Stone.203 Manafort, for his part, told the Office that, shortly after WikiLeaks’s July 22 release, Manafort also spoke with candidate Trump and mentioned that Stone had predicted the release and claimed to have access to WikiLeaks. Candidate Trump responded that Manafort should stay in touch with Stone.204 Manafort relayed the message to Stone, likely on July 25, 2016.205 Manafort also told Stone that he wanted to be kept apprised of any developments with WikiLeaks and separately told Gates to keep in touch with Stone about future WikiLeaks releases.206

According to Gates, by the late summer of 2016, the Trump Campaign was planning a press strategy, a communications campaign, and messaging based on the possible release of Clinton emails by WikiLeaks.207 Gates also stated that Stone called candidate Trump multiple times during the campaign.208 Gates recalled one lengthy telephone conversation between Stone and candidate Trump that took place while Trump and Gates were driving to LaGuardia Airport. Although Gates could not hear what Stone was saying on the telephone, shortly after the call candidate Trump told Gates that more releases of damaging information would be coming.209

Stone also had conversations about WikiLeaks with Steve Bannon, both before and after Bannon took over as the chairman of the Trump Campaign. Bannon recalled that, before joining the Campaign on August 13, 2016, Stone told him that he had a connection to Assange. Stone implied that he had inside information about WikiLeaks. After Bannon took over as campaign chairman, Stone repeated to Bannon that he had a relationship with Assange and said that WikiLeaks was going to dump additional materials that would be bad for the Clinton Campaign.210

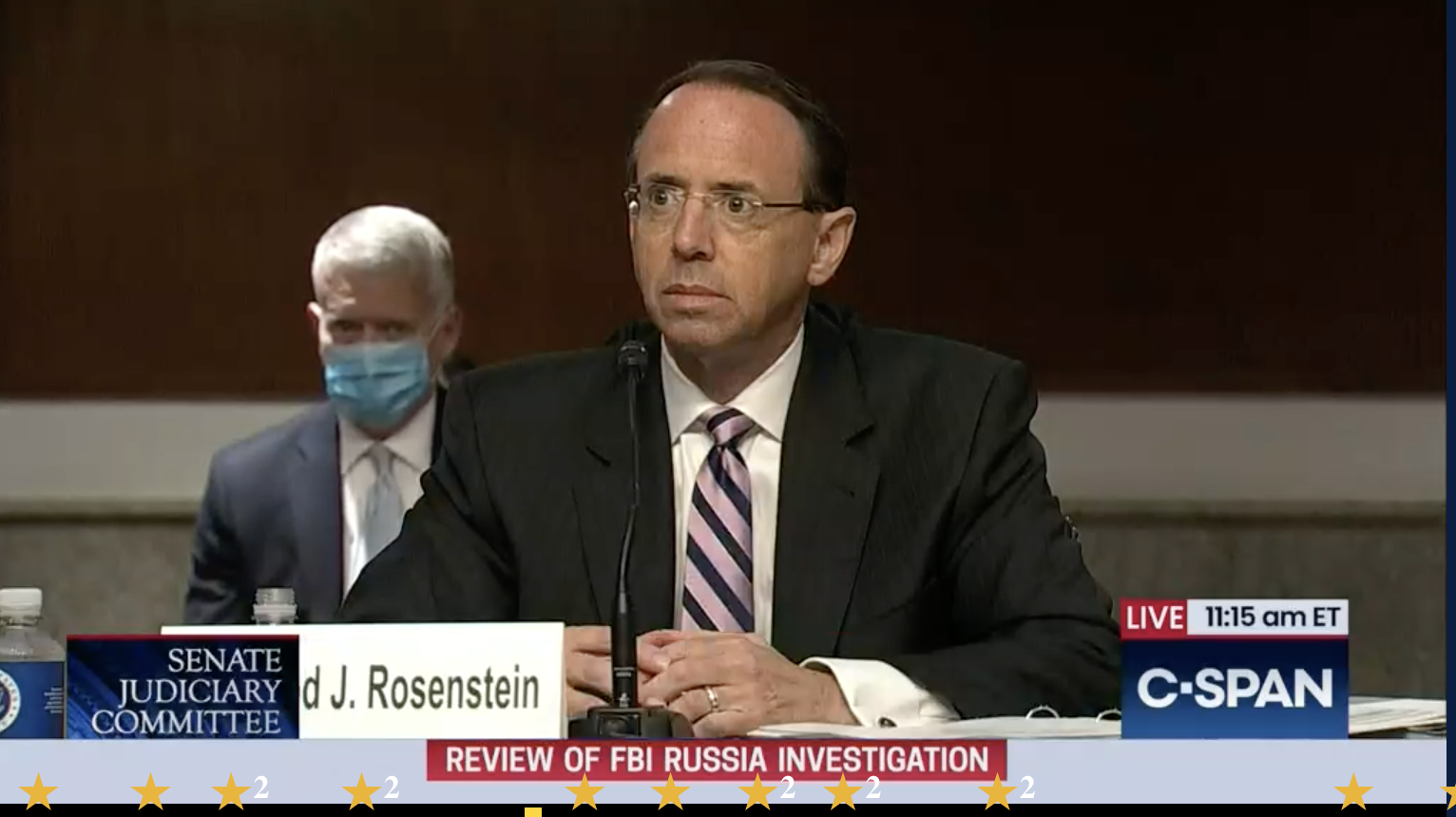

Rosenstein asserted there was no conspiracy in spite of ongoing investigations into a conspiracy

All of which leads me to something I’ve been pondering.

In this post, I analyzed what the Stone warrants suggest about the investigation into him. The investigation appeared to start as an effort to determine whether Stone’s efforts to optimize the hack-and-leak; the Mueller Report seems to explain that nothing Stone was known to have done was criminal. In August 2018, as Stone’s efforts to tamper with witnesses became clear from his press campaign, Mueller’s team obtained the warrants that would lead to his obstruction charges. On August 20, 2018, Mueller obtained warrants for Stone’s cell site location during the election and Guccifer 2.0’s second email account; while different FBI agents obtained those warrants, they got them within minutes of each other.

Then, on September 26 and 27, an FBI agent stationed in Pittsburgh obtained a bunch of warrants, most with gags citing 18 USC 951 and conspiracy, the descriptions of which were withheld in April, apparently because those investigations are ongoing.

*September 24, 2018: Warrant for Stone’s Liquid Web server

*September 26, 2018: Mystery Twitter Account

*September 27, 2018: Mystery Facebook and Instagram Accounts

*September 27, 2018: Mystery Microsoft include Skype

*September 27, 2018: Mystery Google

*September 27, 2018: Mystery Twitter Accounts 2

*September 27, 2018: Mystery Apple ends in R

The warrant targeting several Twitter accounts is sealed in part because, “It does not appear that Stone is fully aware of the full scope of the ongoing FBI investigation.”

In September 2018, Mueller’s team seems to have pursued a new line of investigation, one that the obstruction investigation into Stone may have provided cover for, one that may be ongoing. Mueller was specifically trying to hide that investigation from Stone.

But I’m struck by the date: September 26 and 27

In the wake of a September 21 NYT story, Trump almost fired Rosenstein when people close to Andrew McCabe leaked details of Rosenstein’s musing about wearing a wire to a meeting with Trump. Given Rosenstein’s apparent ignorance of even the public Stone related content — and O’Callaghan’s apparent misrepresentation of those details — I wonder whether Stone wasn’t the only person Mueller was hiding this from.

Rosenstein asserted, as fact, that the Mueller Report showed no evidence of a conspiracy between Trump and Russia (which is inaccurate by itself). He said that in spite of warrants in a still-pending investigation into conspiracy and Agent of a Foreign power involving Stone.