Granting Stay, 11th Circuit Scolds Aileen Cannon for Ignoring Executive Assertions on National Security

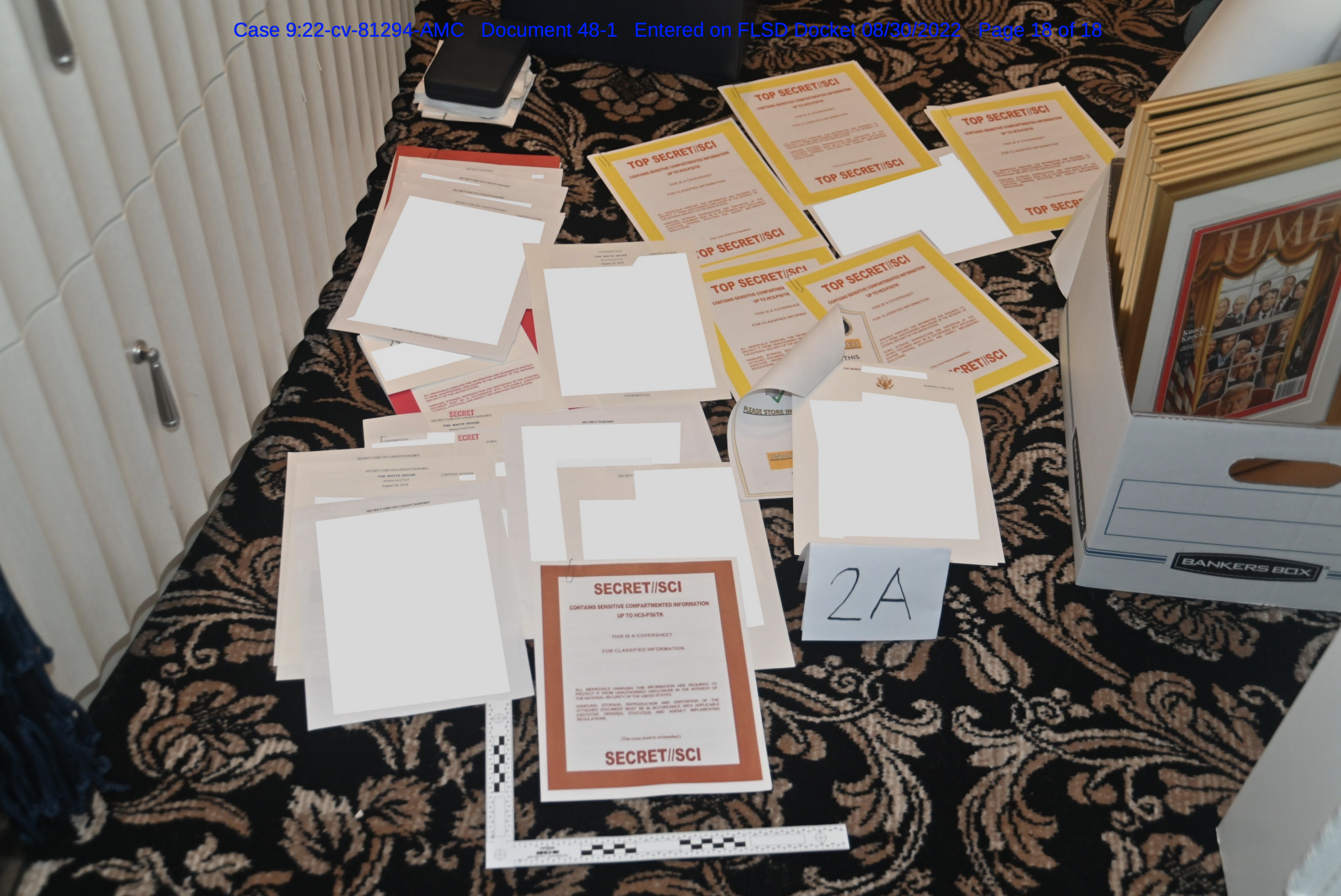

On the same day that NY Attorney General Tish James announced a lawsuit against Trump for his alleged tax cheating and financial fraud, the 11th Circuit granted DOJ a stay of Aileen Cannon’s injunction prohibiting it from using the documents marked as classified in its investigation. But Trump got to go blow smoke to Sean Hannity, so I guess all is not lost.

The opinion was a per curiam opinion written by Trump appointees Britt Grant and Andrew Brasher and Obama appointee Robin Rosenbaum.

Courts don’t question the [current] Executive’s representations about national security

While reserving judgment on the merits question, the opinion was nevertheless fairly scathing about Cannon’s abuse of discretion. Some of this pertained to her jurisdictional analysis (which I’ll return to). But two important implicit admonishments of Cannon’s actions pertain to the deference on national security that courts give to the Executive.

The opinion calls the scheme that Cannon had set up — allowing the Intelligence Community to continue its intelligence assessment but prohibiting any investigation for criminal purposes — untenable. In support, the opinion notes that there’s a sworn declaration from FBI Assistant Director Alan Kohler (the only one in this docket) debunking Cannon’s distinction between national security review and criminal investigation. It notes, twice, that courts must accord great weight to the Executive, including an affidavit. The opinion notes that “no party had offered anything beyond speculation” to undermine this representation.

Returning to the case before us, under the terms of the district court’s injunction, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence is permitted to continue its “classification review and/or intelligence assessment” to assess “the potential risk to national security that would result from disclosure of the seized materials.” Doc. No. 64 at 1–2, 6. But the United States is enjoined “from further review and use of any of the materials seized from Plaintiff’s residence on August 8, 2022, for criminal investigative purposes pending resolution of the special master’s review process.” Id. 23–24.

This distinction is untenable. Through Kohler’s declaration, the United States has sufficiently explained how and why its national-security review is inextricably intertwined with its criminal investigation. When matters of national security are involved, we “must accord substantial weight to an agency’s affidavit.” See Broward Bulldog, Inc. v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 939 F.3d 1164, 1182 (11th Cir. 2019) (quoting Am. Civil Liberties Union v. U.S. Dep’t of Def., 628 F.3d 612, 619 (D.C. Cir. 2011)).

The engrained principle that “courts must exercise the traditional reluctance to intrude upon the authority of the Executive in military and national security affairs” guides our review of the United States’s proffered national-security concerns. United States v. Zubaydah, 142 S. Ct. 959, 967 (2022) (alteration and citation omitted). No party has offered anything beyond speculation to undermine the United States’s representation—supported by sworn testimony—that findings from the criminal investigation may be critical to its national-security review. See Kohler Decl. ¶ 9. According to the United States, the criminal investigation will seek to determine, among other things, the identity of anyone who accessed the classified materials; whether any particular classified materials were compromised; and whether additional classified materials may be unaccounted for. As Plaintiff acknowledges, backwards-looking inquiries are the domain of the criminal investigators. Doc. No. 84 at 15–16. It would be difficult, if not impossible, for the United States to answer these critical questions if its criminal investigators are not permitted to review the seized classified materials. [my emphasis]

Two parties — both Trump and Cannon — did speculate wildly that Kohler’s representations were overblown. Which you can’t do in courts of law, the 11th Circuit says. The more important point was that Cannon totally dismissed the Kohler declaration (even while she didn’t require declarations of others) to sustain her own “untenable” injunction.

The opinion lays out at length how classification works, citing sources Trump also relied on (largely EO 13526 and Navy v. Egan) to effectively show the parts of those citations he ignored. In one such passage, it comes pretty close to suggesting all this should be obvious, even to Aileen Cannon.

The United States also argues that allowing the special master and Plaintiff’s counsel to examine the classified records would separately impose irreparable harm. We agree. The Supreme Court has recognized that for reasons “too obvious to call for enlarged discussion, the protection of classified information must be committed to the broad discretion of the agency responsible, and this must include broad discretion to determine who may have access to it.” Egan, 484 U.S. at 529 (quotation omitted). As a result, courts should order review of such materials in only the most extraordinary circumstances. The record does not allow for the conclusion that this is such a circumstance. [my emphasis]

The way courts have expansively interpreted Navy v. Egan to grant the [current] Executive nearly unfettered authority to dictate matters of classification invites abuse (and screws over defendants in Espionage Act cases). But that is what courts have done. That is what precedent demands. And Cannon’s blithe deviation from that precedent deserved this kind of disdain.

Joe Biden gets to decide Trump doesn’t have a Need to Know

In another section, the opinion makes a finding that goes beyond where the dispute before Cannon has gone (but not beyond where the dispute before Special Master Raymond Dearie has). Even former Presidents can only access classified information if they have a Need to Know.

[W]e cannot discern why Plaintiff would have an individual interest in or need for any of the one-hundred documents with classification markings. Classified documents are marked to show they are classified, for instance, with their classification level. Classified National Security Information, Exec. Order No. 13,526, § 1.6, 3 C.F.R. 298, 301 (2009 Comp.), reprinted in 50 U.S.C. § 3161 app. at 290–301. They are “owned by, produced by or for, or . . . under the control of the United States Government.” Id. § 1.1. And they include information the “unauthorized disclosure [of which] could reasonably be expected to cause identifiable or describable damage to the national security.” Id. § 1.4. For this reason, a person may have access to classified information only if, among other requirements, he “has a need-to-know the information.” Id. § 4.1(a)(3). This requirement pertains equally to former Presidents, unless the current administration, in its discretion, chooses to waive that requirement. Id. § 4.4(3).

Plaintiff has not even attempted to show that he has a need to know the information contained in the classified documents. Nor has he established that the current administration has waived that requirement for these documents. And even if he had, that, in and of itself, would not explain why Plaintiff has an individual interest in the classified documents. [my emphasis]

Trump has tried to claim that because the Presidential Records Act grants him access to his own former official papers, it means he has possessory interest over the classified documents seized from his home. This passage should end that debate, including the complaint Jim Trusty made in Dearie’s court the other day that the President’s lawyers (from the coverage I’ve seen, he didn’t say former) do not have a Need to Know the material in the documents Trump stole. Without DOJ needing to appeal this issue, the 11th Circuit has already sided with Dearie. As I showed here, the fact that even the former President can only access classified information with a Need to Know waiver is laid out explicitly in EO 13526, the Obama EO that (Trump has repeatedly conceded) governed classified information during Trump’s entire Administration and still governs it.

That should settle this issue.

Cannon should never have intervened

Now that I’ve slept some more, I wanted to return to what the 11th Circuit had to say about Judge Cannon’s jurisdictional acrobatics to even rule on Trump’s case.

The summary of this case is a really remarkable description of what has already happened (I’m sure it helped the clerks on that front that they had no page limits). Ominously for Trump’s case, the opinion starts the narrative from the time he left the White House and lays out several moments where Trump failed to invoke privilege or declassification. Trump likes to tell the story starting on August 8 when the FBI arrived at his house out of the blue.

But the opinion is particularly scathing in their description of jurisdiction. It describes that Trump invoked, among other things, equitable jurisdiction.

Regarding jurisdiction, among other bases, Plaintiff asserted that the district court could appoint a special master under its “supervisory authority” and its “inherent power” and could enjoin the government’s review under its “equitable jurisdiction.” Doc. No. 28 at 5–6.

In Trump’s reply to DOJ’s argument that he couldn’t own these documents, the opinion notes, he specifically disclaimed having filed a Rule 41(g), which is where someone moves to demand property unlawfully seized be returned.

Plaintiff appears to view appointment of a special master as a predicate to filing a motion under Rule 41(g) (which allows a person to seek return of seized items), he disclaimed reliance on that Rule for the time being, saying that he “h[ad] not yet filed a Rule 41(g) motion, and [so] the standard for relief under that rule [wa]s not relevant to the issue of whether the Court should appoint a Special Master.” Doc. No. 58 at 6.

Cannon, the opinion notes, claimed to be asserting jurisdiction under equitable jurisdiction even while treating Trump’s request (in which he had not made a Rule 41(g) motion) as a hybrid request.

As to jurisdiction, the district court first concluded that it enjoyed equitable jurisdiction because Plaintiff had sought the return of his property under Rule 41(g), which created a suit in equity.1 Because its jurisdiction was equitable, the district court explained, it turned to the Richey factors to decide whether to exercise equitable jurisdiction.2

Half that page of the opinion consists of footnotes, recording that Trump’s claims about Rule 41(g) have been all over the map.

1 As we have noted, Plaintiff disclaimed having already filed a Rule 41(g) motion in his initial reply to the government. Doc. No. 58 at 6. Yet in the same filing, Plaintiff stated that he “intends” to assert that records were seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment and the Presidential Records Act and are “thus subject to return” under Rule 41(g). Id. at 8; see also id. at 18 (“Rule 41 exists for a reason, and the Movant respectfully asks that this Court ensure enough fairness and transparency, even if accompanied by sealing orders, to allow Movant to legitimately and fulsomely investigate and pursue relief under that Rule.”). The district court resolved this situation by classifying Plaintiff’s initial filing as a “hybrid motion” that seeks “ultimately the return of the seized property under Rule 41(g).” Doc. No. 64 at 6–7

2 Richey v. Smith, 515 F.2d 1239, 1243–44 (5th Cir. 1975) (outlining the standard for entertaining a pre-indictment motion for the return of property under Rule 41(g)). Because the Fifth Circuit issued this decision before the close of business on September 30, 1981, it is binding precedent in the Eleventh Circuit. See Bonner v. City of Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206, 1209 (11th Cir. 1981) (en banc).

In reviewing Trump’s response to the government’s motion for a stay, the opinion notes that Trump claims to have Rule 41(g) standing — with respect to the classified documents.

As the opinion laid out, in denying the stay, Cannon relied on claimed uncertainty around the status of the classified documents to find for Trump.

On September 15, the district court denied a stay pending appeal and appointed a special master. Doc. No. 89. In explaining the basis for its decision, the district court first reasoned that it was not prepared to accept, without further review by a special master, that “approximately 100 documents isolated by the Government . . . [were] classified government records.” Doc. No. 89 at 3. Second, the district court declined to accept the United States’s argument that it was impossible that Plaintiff could assert a privilege for some of the documents bearing classification markings. Doc. No. 89 at 3–4

The opinion doesn’t come to any conclusions about all this nonsense from a jurisdictional position. It doesn’t have to. But it did capture conflicting claims that Trump made and Cannon’s reliance on a “hybrid” claim to avoid pinning Trump down.

The reason the 11th Circuit didn’t have to resolve all this is because, regardless of which basis Cannon claimed to have intervened, Richey governs (which is exactly what Jay Bratt said in the hearing before Cannon, as I laid out here).

Our binding precedent states that when a person seeks return of seized property in pre-indictment cases, those actions “are governed by equitable principles, whether viewed as based on [Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure] 41[(g)] or on the general equitable jurisdiction of the federal courts.” Richey v. Smith, 515 F.2d 1239, 1243 (5th Cir. 1975). Here, while Plaintiff disclaimed that his motion was for return of property as specified in Rule 41(g), he asserted that equitable jurisdiction existed. And the district court relied on both Rule 41(g) and equitable jurisdiction in its orders. Doc. No. 64 at 8–12. Either way, Richey teaches that equitable principles control.

And the first prong of Richey — and the most important one — is whether there has been a Fourth Amendment violation. Cannon says there has not. That should be game over.

We begin, as the district court did, with “callous disregard,” which is the “foremost consideration” in determining whether a court should exercise its equitable jurisdiction. United States v. Chapman, 559 F.2d 402, 406 (5th Cir. 1977). Indeed, our precedent emphasizes the “indispensability of an accurate allegation of callous disregard.” Id. (alteration accepted and quotation omitted).

Here, the district court concluded that Plaintiff did not show that the United States acted in callous disregard of his constitutional rights. Doc. No. 64 at 9. No party contests the district court’s finding in this regard. The absence of this “indispensab[le]” factor in the Richey analysis is reason enough to conclude that the district court abused its discretion in exercising equitable jurisdiction here. Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406. But for the sake of completeness, we consider the remaining factors. [my emphasis]

Because the opinion continued this analysis, this determination: that Cannon never had the authority to intervene in the first place, is not the most important part of the 11th Circuit’s grant of a stay. But it would be important going forward on the appeal (and may influence how broadly DOJ appeals Cannon’s decision).

Later in the opinion, the 11th Circuit noted that Cannon had also suggested she might be invoking jurisdiction under “inherent supervisory authority,” though it couldn’t really tell. It then mocked the possibility she could exercise inherent authority over classified documents.

The district court referred fleetingly to invoking its “inherent supervisory authority,” though it is unclear whether it utilized this authority with respect to the orders at issue in this appeal. Doc. No. 64 at 1, 7 n.8. Either way, the court’s exercise of its inherent authority is subject to two limits: (1) it “must be a reasonable response to the problems and needs confronting the court’s fair administration of justice,” and (2) it “cannot be contrary to any express grant of or limitation on the district court’s power contained in a rule or statute.” Dietz v. Bouldin, 136 S. Ct. 1885, 1892 (2016) (quotation omitted). The district court did not explain why the exercise of its inherent authority concerning the documents with classified markings would fall within these bounds, other than its reliance on its Richey-factor analysis. We have already explained why that analysis was in error.

The 11th Circuit has not just said that DOJ has cause for a stay, but it has said that Cannon should never have intervened in the first place.

Richey within Nken

Because of what I just laid out — that the 11th Circuit decided that Cannon should never have intervened, but then went onto consider a bunch of other issues — and because I laid out the structure of both sides’ arguments in this post, I want to lay out the structure of the 11th Circuit’s analysis here. It nests the likelihood of DOJ’s success, using Richey analysis, inside their overall analysis of whether to grant the stay under Nken.

The four Nken factors are:

(1) whether the stay applicant has made a strong showing that he is likely to succeed on the merits;

(2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay;

(3) whether issuance of the stay will substantially injure the other parties interested in the proceeding; and

(4) where the public interest lies.

The four very similar Richey factors are:

(1) whether the government has “displayed a callous disregard for the constitutional rights” of the subject of the search;

(2) whether the plaintiff has an individual interest in and need for the material whose return he seeks

(3) whether the plaintiff would be irreparably injured by denial of the return of his property; and

(4) whether the plaintiff has an adequate remedy at law for the redress of his grievance.

Here’s how it looked in practice:

- Is DOJ likely to succeed on the merits?

- Was Cannon’s Richey analysis correct?

- Is there any claim of callous disregard for Trump’s rights? No. Cannon said so.

- Does Trump have an individual interest in this material?

- Cannon’s analysis applies to “medical documents, correspondence related to taxes, and accounting information,” not to classified documents.

- There would be no individual interest in classified documents and Trump has no Need to Know these documents.

- Trump has provided no proof he declassified any of these documents and even if he had, it would not change its content or make it a personal document.

- Would Trump be irreparably harmed? Cannon said it might be improperly disclosed, it might include privileged material, and he might be prosecuted.

- USG limits dissemination of classified documents to limit unauthorized dissemination, not to leak them.

- Trump has not asserted privilege over any of the classified documents.

- Except in cases of harassment, courts don’t intervene in criminal prosecutions

- Does Trump have another remedy?

- Cannon said that he would have no legal means of seeking return of his property, but then also acknowledged that he hadn’t used the means, a Rule 41(g) motion, that he would take to get return of his property.

- Was Cannon’s Richey analysis correct?

- Would the US suffer irreparable harm?

- Cannon’s injunction is untenable. Kohler has explained that the criminal investigation is inextricably intertwined with the national security review. The government needs to be able to do a backward looking review of what happened with the documents.

- DOJ says sharing the documents with the Special Master and Trump’s counsel would impose irreparable harm, and under Navy v. Egan, we agree.

- Has Trump shown he’ll be injured?

- Trump neither owns nor has a personal interest in these classified documents.

- “Bearing the discomfiture and cost of a prosecution for crime even by an innocent person is one of the painful obligations of citizenship.”

- The government’s use of these documents that don’t include privileged information would not risk disclosure of privileged information.

- What about public interest?

- According to the classification system, investigating the disclosure of documents marked Top Secret by definition involves investigating whether something that could cause “exceptionally grave damage to national security” was disclosed. So a stay is in the public interest.

One reason I laid this structure out is because, in the filings before the 11th Circuit, the various harms were muddled. Trump even argued (because DOJ treated them in tandem, I think) that the government had merged DOJ and public interest. Trump (and Cannon) had effectively tied the harm of Trump to the harm of the public.

As this makes it clear, Trump’s harm is assessed at both levels of analysis. Though the 11th Circuit’s Richey analysis says that once you’ve found Trump’s rights were not harmed (in blue above), you need go no further. But on the Nken analysis, the question is whether the government would be irreparably harmed (in red above). And there, once you accept the US system of classification, in which the disclosure of things that are classified Top Secret by definition would cause exceptionally grave harm, then there’s no contest.

Update: Judge Cannon has removed the classified documents from those included in the seized materials covered by her order.

Go to emptywheel resource page on Trump Espionage Investigation.