Radicalized by Trump: A Tale of Two Assault Defendants

Journalists and the public who called into Magistrate Judge Robin Meriweather’s public access line yesterday presumably called in to hear the initial hearings for a range of January 6 defendants. There were the two life-long friends, Jennifer Ruth Parks and Esther Schwemmer, whose lawyers went to some effort to ensure the no contact provision imposed upon their arrests was explicitly dropped in release conditions as they await resolution of their misdemeanor trespass charges. Right wing media figure Billy Tryon from upstate NY, accused of trespassing, had his appearance without incident. Somehow Albuquerque Cosper Head, accused in one of the more brutal attacks on January 6, the group assault on Brian Fanone, was a side-story of this hearing.

But the hearing — scheduled for an hour but lasting far longer — ended up posing an apt lesson in the human tragedy created by Trump’s radicalization of his supporters.

Even before the judge came in, Landon Copeland had disrupted the proceedings for others. A friend who had logged into the Zoom conference — which is supposed to be restricted to official participants like defendants, lawyers, and pretrial services officers — got booted for using an obscene name. Copeland took a week to travel from Southern Utah to the insurrection with his girlfriend. He is accused of assaulting cops and participating in a civil disorder along with the trespassing charges that virtually all January 6 defendants get charged with.

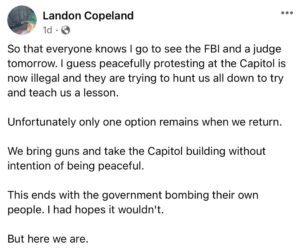

After he was arrested, Copeland was let out on personal recognizance, but in the wake of learning he’d face consequences for his participation in the riot, he posted threats of violence to his Facebook account.

Plus, Copeland had a recent arrest for violence. He was arrested in early 2020 for stealing a car and lighting it on fire.

Copeland’s interruptions early in the hearing seemed like rage about being held accountable and incomprehension about both the seriousness of his plight and basic things like managing a conference call appearance. As he started screaming, most on the line realized what the outbursts would do for his defense against charges that he lost control on January 6, blew off authority, and beat up some cops, and multiple lawyers and court personnel kept trying to counsel him to shut up. He even promised he would be quiet at one point, only to interrupt as the government described base-level pre-trial release conditions by asking, “Is any of this negotiable?”

Perhaps the most telling exchange came when Anthony Antonio’s attorney, Joseph Hurley, started into a long explanation about why his client — who was arrested in Delaware, lives in South Carolina, but needs to travel nationally for his job — should not have any district level travel restrictions on his release conditions.

If you go by his his arrest affidavit, Antonio is as dangerous as Copeland. He’s not charged with assault, but is charged with participating in a civil disorder, obstruction, and depredation of property (the charge used to add detention enhancements to militia conspirators). He showed up wearing a 3%er patch and a bullet proof vest. He was involved in the fight in the Lower West Tunnel. And while he grabbed a bullhorn and emphasized keeping the riot peaceful, after he did so, he broke into an office and trashed the place, allegedly coming away wielding a table leg as a weapon.

According to Antonio’s arrest affidavit, the FBI IDed him first by releasing his image in a BOLO, then responding to a tip provided in response.

That’s not what Hurley said. Hurley told Magistrate Meriweather that days after the riot, Antonio had come to his Wilmington, DE office and overcome Hurley’s initial resistance to work with any January 6 defendants by convincing him he was really an up-standing citizen whose mind had been rotted by Fox. This is not a new ploy. Many attorneys representing January 6 defendants have claimed that their clients did what they did because they had been caught up in Trump’s lies. In this case, Hurley claimed that the riot had cured his client of his belief in Trump, but also made him realize that the six months he spent with a bunch of guys living in Naperville during COVID had given him “Foxitis,” and led him to deviate from a successful life in sales to participate in a mob.

Hurley led the growing call-in audience to believe that Antonio came to him and they went to the FBI. But the arrest affidavit suggests that Antonio and Hurley first met the FBI on February 4, long after other witnesses turned him in, and in that meeting, Hurley downplayed his involvement and claimed the cops let them do what they were doing.

On February 4, 2021, FBI agents interviewed ANTONIO with his attorney present. ANTONIO stated that he came to Washington, D.C. because then-President Trump told him to do so. He admitted that he was at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, and saw that there were barriers up and that people were clashing with the police. ANTONIO admitted that he was on the scaffolding that day, but stated that another person also on the scaffolding said, “I’m media,” showed ANTONIO a badge, and said that ANTONIO could be on the scaffolding because he (ANTONIO) was “with” the person with the badge. ANTONIO told the agents that he was advising others not to come up on the scaffolding because he was worried it would fall.

When asked if he heard the police give any commands, ANTONIO claimed that when he was on the scaffolding he heard announcements over a speaker, but could not understand what was being said. ANTONIO said that he saw the barriers pushed over by people and that the police were gone. According to ANTONIO, he thought “I guess they gave us the steps, they said we could be on the steps, they’re, they’re done.” ANTONIO also told agents that when he was on the “steps,” – contextually referring to the steps of the Lower West Terrace – he observed a person who was bleeding from the head, and he tried to make a path through the mass of people to get the injured person aid.

When the FBI asked Antonio whether he had entered the room of the Capitol in which — he told VDARE — [we] “broke everything,” Hurley refused to let him answer.

ANTONIO was asked if he was ever in a position to observe what was going on inside the Capitol building. ANTONIO responded that there was a woman yelling, “we broke the window,” and through that window he observed people smashing furniture and piling it in front of the door to create a barricade. ANTONIO reported that because of the chemical irritants in his eyes, he was rubbing them, but he could hear the sound of the property being broken inside the room. When asked if he went inside the Capitol building, ANTONIO’s lawyer stated, “Next question, please,” and the agents complied with that request.

Plus, there’s a key gap — at least in the April 14 affidavit, dated six days before his arrest — in the narrative of what Antonio did. Surveillance video shows Antonio approaching the cops inside the tunnel bearing a stolen riot shield, but that video, at least, doesn’t show what he did there.

Once he made his way to the front of the tunnel, ANTONIO turned his hat around so that the bill was facing backwards. At this time in the investigation, due to the angle of the surveillance video, it is unclear what actions ANTONIO took at the front of the tunnel. Approximately two minutes later, ANTONIO left the tunnel with the riot shield still in his possession. About twenty minutes later, ANTONIO reentered the tunnel and pushed his way towards the front of the crowd; he was ultimately pushed out of tunnel. As before, it is unclear at this point, what ANTONIO did while inside the tunnel due to the angle of the surveillance video.

Antonio told the FBI, at what seems to have been a well-rehearsed interview with the famously showy Hurley (who claimed the only attorney who could vouch for him in DC was a guy named Joe Biden, but that guy isn’t admitted to the DC Bar), that he looked into Michael Fanone’s eyes and saw death and realized things had gone too far.

ANTONIO told the agents that while he was on the steps, he observed about six men drag a police officer down the steps. He claimed that he heard the sound of a taser, looked in that direction, believing that the officer was using the taser against the crowd, but “it was the exact opposite.” Your affiant is aware that this police officer, Officer 1, was tased by participants in the riot. ANTONIO claimed that he locked eyes with the officer, who said, “help, help,” and ANTONIO could see “death in the man’s eyes.” ANTONIO stated he would not be able to get the image of the officer out of his head. ANTONIO reported that this was the point he said to himself something was wrong and not right. According to ANTONIO, he did not help the officer, and “missed my judgement, I didn’t help him when I should of.”

But that was before he entered the Capitol and trashed the joint. And when the guy wearing a 3%er patch and flashing 3%er symbols was asked about affiliations with right wing extremists, he simply said he knew of but was not affiliated with the Proud Boys.

Anyway, Hurley was telling the carefully rehearsed story about how his client’s “Foxitis” explains his role in the insurrection and claiming that his client was cooperating and they would be happy to waive speedy trial for years to let all the bad people be prosecuted first at a dial-in hearing that live coverage about Copeland’s disruptions had attracted more attention to, and Copeland interrupted this speech and said, “This is not pertinent.”

Copeland then continued to hijack the conference between patient court employees muting him, him hanging up, and one after another services personnel calling in to see if they could help.

It was difficult to tell how much of Copeland’s interruptions were about the PTSD that, it was mentioned at the trial, he suffered from or from ties the Sovereign citizen movement in southern Utah. His service and his “taxes” (which he made clear included his child support) were recurrent theories.

I need a bunch of stuff, I’m a veteran, and you owe this to me, I got shot at in Iraq. You guys just done fucked this up. I don’t know who you are. I’m clear out here in the middle of the desert in no man’s land. You can’t come get me if I don’t you to.

An FBI Agent, who was prepared to talk about his threats on Facebook, showed up. But by then, Judge Merriweather had decided she couldn’t move forward without a competence hearing, all exacerbated by the challenge of finding someone Copeland trusted enough to encourage him to attend the hearing. It’s impossible to tell where the very real PTSD ends and the Trump-stoked resentments begin.

Against the background of Hurley claiming Fox and Trump had made his client crazy enough to join a riot, Copeland’s outbursts made it clear how dangerous was the way that Trump has exacerbated the instability of his supporters, how the effect leaves us with no good options.

But claiming his client had been temporarily made crazy by Fo worked for Hurley, at least. His client got his national release conditions.

Pezzola

Pezzola