Russia Russia Russia

In a piece describing how, after Trump attempted to publicly humiliate Volodymyr Zelenskyy, talks on normalizing relations with Russia (negotiated by Kirill Dmitriev, of Mueller Report fame) will accelerate…

There is also renewed optimism in Moscow that, with President Zelensky at odds with President Trump and his team, difficult negotiations to end the war in Ukraine will now take a back seat to a raft of potentially lucrative US-Russia economic deals already being tabled behind closed doors.

[snip]

Already the Kremlin’s key economic envoy to the talks, Kirill Dmitriev, has told CNN that cooperation with the US could “include energy” deals of some kind, but no details have been announced.

Separately, the Financial Times is reporting that there have been efforts to involve US investors in the restarting Russia’s Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Europe, which Germany halted at the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Dmitriev has called for the Trump administration and Russia to start “building a better future for humanity,” and to “focus on investment, economic growth, AI breakthroughs,” and long-term joint scientific projects like “Mars exploration,” even posting a highly produced computer graphic, on Elon Musk’s X social media platform, showing an imagined joint US-Russia-Saudi mission to Mars, on board what appears to be a Space X rocket.

CNN described literal “bewilder[ment]” about why Trump would sell out America’s allies.

[W]hy the US president would choose the Kremlin over America’s traditional partners remains the subject of intense speculation.

Much of it, like the frequent suggestion that Trump is somehow a Kremlin agent, or beholden to Putin, is without evidence.

Perhaps the right-wing US ideological fantasy that Russia is a natural US ally in a future confrontation with China, and can be broken away from its most important backer, is motivating Washington’s dramatic geopolitical shift.

But for many bewildered observers, both explanations for Trump’s extraordinary pivot to the Kremlin seem equally misplaced. [my emphasis]

CNN asserted there’s no evidence to back the claim that Trump is “beholden to Putin” in spite of the fact that Russia helped Trump win in 2016, after which Dmitriev reached out and discussed a bunch of investments as a way to improve relations. CNN asserted there’s no evidence to back the claim that Trump is “beholden to Putin” in spite of the fact that Russia attempted to help Trump win in 2020 at least by sending disinformation framing Joe Biden and his kid via Russian agent Andrii Derkach to Trump’s personal lawyer. CNN asserted there’s no evidence to back the claim that Trump is “beholden to Putin” in spite of the fact that Derkach made similar efforts in 2024, and a bunch of Russian malign influence efforts (possibly including bomb threats that forced the evacuation of Democratic precincts) similarly aimed to help Trump and others who would “oppose aid to Ukraine.”

CNN asserted there’s no evidence to back the claim that Trump is “beholden to Putin” in spite of the fact that a key Putin advisor, Nikolay Patrushev, said this in November:

In his future policies, including those on the Russian track US President-elect Donald Trump will rely on the commitments to the forces that brought him to power, rather than on election pledges, Russian presidential aide Nikolay Patrushev told the daily Kommersant in an interview.

“The election campaign is over,” Patrushev noted. “To achieve success in the election, Donald Trump relied on certain forces to which he has corresponding obligations. As a responsible person, he will be obliged to fulfill them.”

He agreed that Trump, when he was still a candidate, “made many statements critical of the destructive foreign and domestic policies pursued by the current administration.”

“But very often election pledges in the United States can iverge [sic] from subsequent actions,” he recalled.

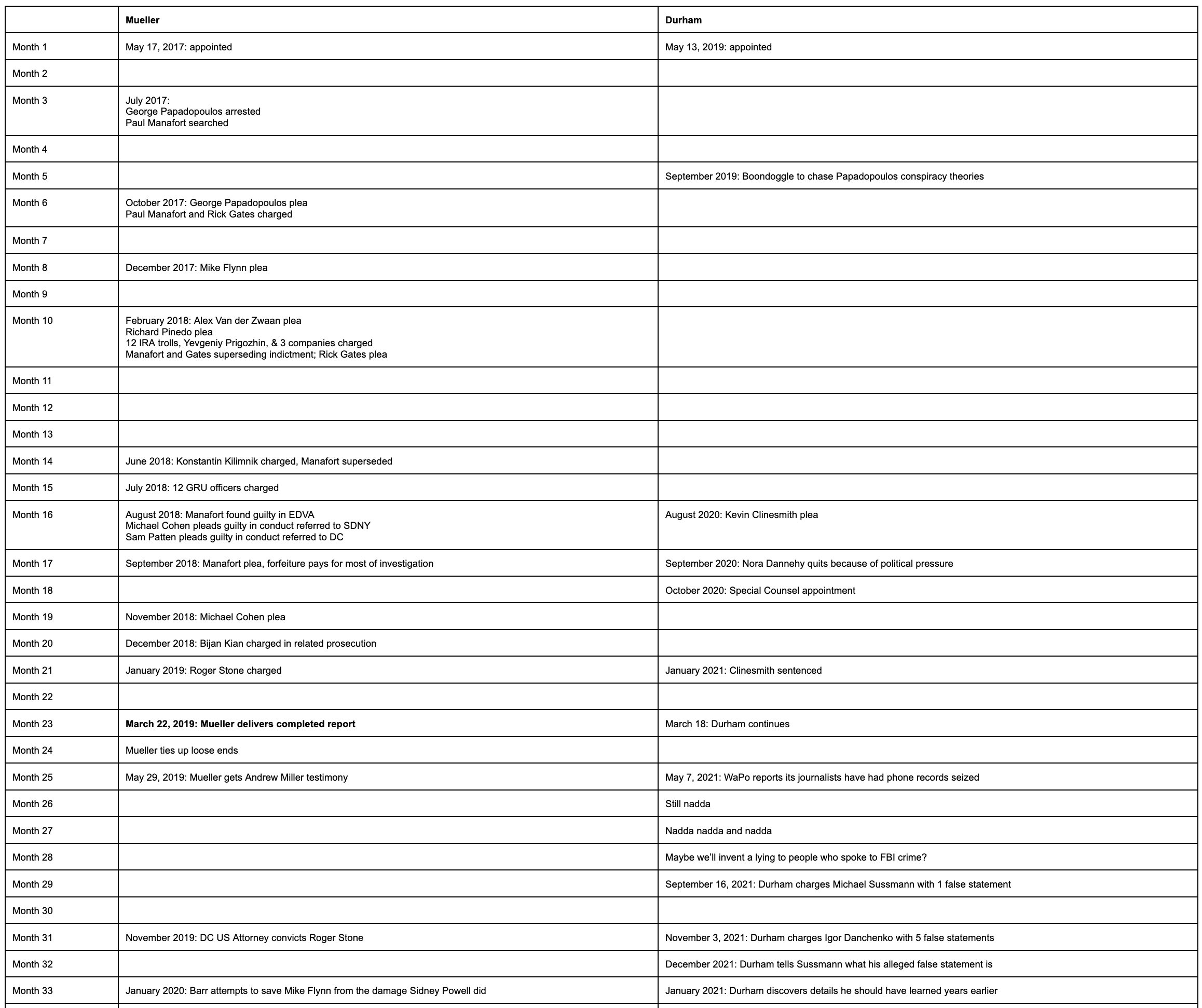

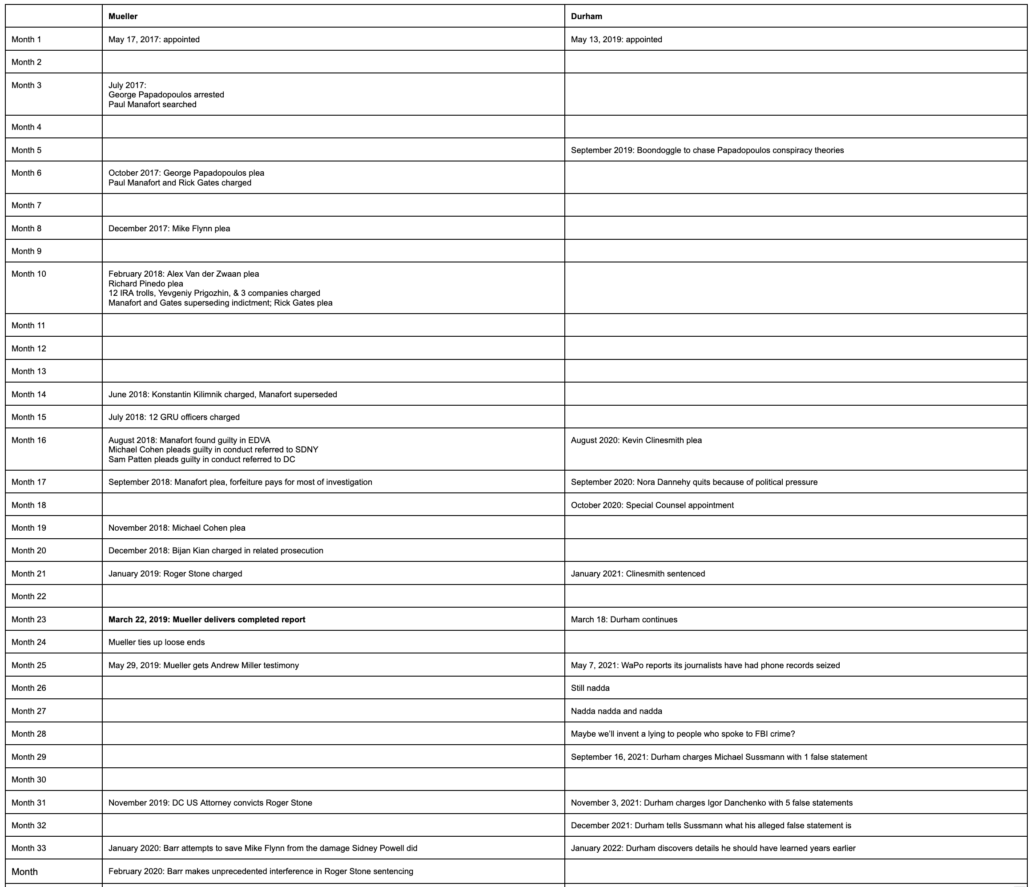

As people puzzle through this bewilderment, as people puzzle through why Trump appointed people who undermined the Russian investigation to lead the FBI, the boilerplate about what Robert Mueller discovered about Russia’s 2016 efforts to help Trump remains wildly inadequate, as in this recent version in a story on Don Bongino’s propaganda about the investigation.

Mueller’s inquiry found repeated contacts between Russia-linked entities and Trump campaign advisers, but didn’t establish a conspiracy between the two.

Mueller didn’t establish a conspiracy between Trump and Russia. But such boilerplate always leaves out that his key aides lied about the true nature of those contacts, which is a big reason why we wouldn’t know if there had been one.

In the Mueller investigation, Trump’s campaign manager, foreign policy advisor, National Security Adviser, personal lawyer, and rat-fucker were all adjudged to have lied about the true nature of Trump’s ties to Russia from the first campaign.

Let’s unpack that even further.

- Trump’s personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, confessed to lying to hide the direct contact he had during the campaign with Dmitry Peskov’s office in pursuit of an impossibly lucrative Trump Tower deal, a deal that would have required lifting sanctions to complete. Cohen confessed to lying to cover up his conversations with Trump about that impossibly lucrative Trump Tower deal. His confession meant that when Trump disclaimed pursuing business deals with Russia — in the same July 27, 2016 press conference where he asked Russia to hack Hillary some more and said he might bless Russia’s seizure of Crimea — Trump lied to cover up that dangle for an impossibly lucrative Trump Tower deal.

- Trump’s foreign policy advisor, George Papadopoulos (who was overtly involved in Derkach’s efforts last year), confessed to lying about the timing and circumstances of learning that Russia had thousands of Hillary’s emails and planned to release them to hurt her campaign. He lied about the other Russians that Joseph Mifsud introduced to Papadopoulos. After he pled guilty, Papadopoulos remembered and then unremembered telling his boss on the campaign, Sam Clovis, about the emails. He also claimed to forget what his own notes describing a proposed meeting in September 2016 with Putin’s team pertained to (notes that also mentioned Egypt and involved Walid Phares, whom investigators suspected of having a role in any $10 million payment Egypt made to Trump).

- A jury found Trump’s rat-fucker, Roger Stone, guilty of lying to cover up the nature and source of his advance notice of the Russian hack-and-leak campaign. Over the course of the investigation, the FBI found evidence Stone knew of several of the Russian personas before they went public. There’s good reason to believe that Stone got advance knowledge, in mid-August 2016, of the substance of select emails from the later John Podesta leak. When prosecutors indicted Stone, they were very keen to obtain a notebook containing notes he took of all his conversations with Trump during the 2016 campaign. Stone stayed out of jail by repeatedly claiming prosecutors offered leniency to get knowledge of those contacts.

- Don Jr. refused to testify before a grand jury, an appearance that presumably would have included questions about his understanding of the June 9 meeting at which Aras Agalarov offered dirt on Hillary in exchange for sanctions relief.

- Amy Berman Jackson ruled that Trump’s campaign manager, Paul Manafort, reneged on his plea agreement, in part, by lying about his August 2, 2016 meeting with Konstantin Kilimnik, at which three topics were discussed: The campaign’s strategy to win swing states, how Manafort could get paid millions, and a plan to carve up Ukraine. In 2021, Treasury stated as fact that Kilimnik. was a “known Russian Intelligence Services agent” who had “provided the Russian Intelligence Services with sensitive information on polling and campaign strategy” during 2016. The report went on to explain that, “Kilimnik sought to promote the narrative that Ukraine, not Russia, had interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” a narrative Trump keeps pushing.

- Trump’s National Security Adviser, Mike Flynn, confessed, twice, to lying about his efforts to undercut Barack Obama’s policy, including efforts to sanction Russia in response to the 2016 attack. There’s a good deal of evidence — including Flynn’s assurances to Sergey Kislyak that the “Boss is aware” — that Trump was involved in those efforts.

All of the people who lied to cover up the true nature of Trump’s Russian contacts in 2016, save Michael Cohen, were pardoned.

So was one other person — someone else who probably lied about the nature of Trump’s Russian contacts in 2017.

In the section describing his declination decisions, Mueller explained that there were three other people who probably lied, but whom he wasn’t charging.

We also considered three other individuals interviewed–[redacted]–but do not address them here because they are involved in aspects of ongoing investigations or active prosecutions to which their statements to this Office may be relevant.

The report itself and the 302s of Steve Bannon’s testimony, which evolved over the course of four interviews to more closely approximate the evidence, suggests Bannon could be one of those three (after all, Bannon, Trump’s other campaign manager, was a key witness at the Stone trial).

Not least because the report describes a pretty big discrepancy between Bannon’s testimony and Erik Prince’s regarding conversations the latter had with Kirill Dmitriev, now starring in negotiations about Russia. And both men played dumb about where the texts they exchanged in that period disappeared to.

Prince said that he met Bannon at Bannon’s home after returning to the United States in mid-January and briefed him about several topics, including his meeting with Dmitriev.1086 Prince told the Office that he explained to Bannon that Dmitriev was the head of a Russian sovereign wealth fund and was interested in improving relations between the United States and Russia.1087 Prince had on his cellphone a screenshot of Dmitriev’s Wikipedia page dated January 16, 2017, and Prince told the Office that he likely showed that image to Bannon.1088 Prince also believed he provided Bannon with Dmitriev’s contact information.1089 According to Prince, Bannon instructed Prince not to follow up with Dmitriev, and Prince had the impression that the issue was not a priority for Bannon.1090 Prince related that Bannon did not appear angry, just relatively uninterested.1091

Bannon, by contrast, told the Office that he never discussed with Prince anything regarding Dmitriev, RDIF, or any meetings with Russian individuals or people associated with Putin.1092 Bannon also stated that had Prince mentioned such a meeting, Bannon would have remembered it, and Bannon would have objected to such a meeting having taken place.1093

The conflicting accounts provided by Bannon and Prince could not be independently clarified by reviewing their communications, because neither one was able to produce any of the messages they exchanged in the time period surrounding the Seychelles meeting. Prince’s phone contained no text messages prior to March 2017, though provider records indicate that he and Bannon exchanged dozens of messages.1094 Prince denied deleting any messages but claimed he did not know why there were no messages on his device before March 2017.1095 Bannon’s devices similarly contained no messages in the relevant time period, and Bannon also stated he did not know why messages did not appear on his device.1096 Bannon told the Office that, during both the months before and after the Seychelles meeting, he regularly used his personal Blackberry and personal email for work-related communications (including those with Prince), and he took no steps to preserve these work communications.1097

The lies Trump’s top aides told to hide aspects of the 2016 Russian effort — his campaign manager, foreign policy advisor, National Security Adviser, personal lawyer, and rat-fucker — along with gaps left by both Jr and Bannon’s testimony (note, Bannon’s testimony also conflicts with Mike Flynn’s regarding whether he was privy to Flynn’s effort to undermine sanctions) trace out clear outlines of a quid pro quo: a serial agreement to reward Russia by acceding to carve up Ukraine and an agreement to lift sanctions, in exchange for help getting elected.

And here we are, eight years later, utterly bewildered why Trump might be in such a rush to deliver up Ukraine to Russia and lift sanctions to pursue business deals, precisely the quo outlined by the lies told years ago.

Really? How is anyone bewildered about this?

On November 11, one of Putin’s closest allies complained about how, “election pledges in the United States can [d]iverge from subsequent actions.” Patrushev warned that, this time, Trump will “be obliged to fulfill” his “corresponding obligations.”

And what we are seeing in real time, in plain sight, protected by an Attorney General who has promised to investigate neither the campaign assistance nor the bribery, is Trump picking up precisely where things left off in 2017.

Starting with the very same offers Dmitriev was offering eight years ago.

Update: I have taken out a reference to sanctions with regards to Kirill Dmitriev.