60 Minutes Comey Refutes 60 Minutes Comey

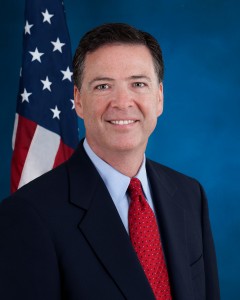

Today, Jim Comey will give what will surely be an aggressively moderated (by Ben Wittes!) talk at Brookings, arguing that Apple should not offer its customers basic privacy tools (congratulations to NYT’s Michael Schmidt for beating the rush of publishing credulous reports on this speech).

Today, Jim Comey will give what will surely be an aggressively moderated (by Ben Wittes!) talk at Brookings, arguing that Apple should not offer its customers basic privacy tools (congratulations to NYT’s Michael Schmidt for beating the rush of publishing credulous reports on this speech).

Mr. Comey will say that encryption technologies used on these devices, like the new iPhone, have become so sophisticated that crimes will go unsolved because law enforcement officers will not be able to get information from them, according to a senior F.B.I. official who provided a preview of the speech.

Never mind the numbers, which I laid out here. While Apple doesn’t break out its device requests last year, it says the vast majority of the 3,431 device requests it responded to last year were in response to a lost or stolen phone request, not law enforcement seeking data on the holder. Given that iPhones represent the better part of the estimated 3.1 million phones that will be stolen this year, that’s a modest claim. Moreover, given that Apple only provided content off the cloud to law enforcement 155 times last year, it’s unlikely we’re talking a common law enforcement practice.

At least not with warrants. Warrantless fishing expeditions are another issue.

As far back as 2010, CBP was conducting 4,600 device searches at the border. Given that 20% of the country will be carrying iPhones this year, and a much higher number of the Americans who cross international borders will be carrying one, a reasonable guess would be that CBP searches 1,000 iPhones a year (and it could be several times that). Cops used to be able to do the same at traffic stops until this year’s Riley v, California decision; I’ve not seen numbers on how many searches they did, but given that most of those were (like the border searches) fishing expeditions, it’s not clear how many will be able to continue, because law enforcement won’t have probable cause to get a warrant.

So the claims law enforcement is making about needing to get content stored on and only on iPhones with a warrant doesn’t hold up, except for very narrow exceptions (cops may lose access to iMessage conversations if all users in question know not to store those conversations on iCloud, which is otherwise the default).

But that’s not the best argument I’ve seen for why Comey should back off this campaign.

As a number of people (including the credulous Schmidt) point out, Comey repeated his attack on Apple on the 60 Minutes show Sunday.

James Comey: The notion that we would market devices that would allow someone to place themselves beyond the law, troubles me a lot. As a country, I don’t know why we would want to put people beyond the law. That is, sell cars with trunks that couldn’t ever be opened by law enforcement with a court order, or sell an apartment that could never be entered even by law enforcement. Would you want to live in that neighborhood? This is a similar concern. The notion that people have devices, again, that with court orders, based on a showing of probable cause in a case involving kidnapping or child exploitation or terrorism, we could never open that phone? My sense is that we’ve gone too far when we’ve gone there

What no one I’ve seen points out is there was an equally charismatic FBI Director named Jim Comey on 60 Minutes a week ago Sunday (these are actually the same interview, or at least use the same clip to marvel that Comey is 6’8″, which raises interesting questions about why both these clips weren’t on the same show).

That Jim Comey made a really compelling argument about how most people don’t understand how vulnerable they are now that they live their lives online.

James Comey: I don’t think so. I think there’s something about sitting in front of your own computer working on your own banking, your own health care, your own social life that makes it hard to understand the danger. I mean, the Internet is the most dangerous parking lot imaginable. But if you were crossing a mall parking lot late at night, your entire sense of danger would be heightened. You would stand straight. You’d walk quickly. You’d know where you were going. You would look for light. Folks are wandering around that proverbial parking lot of the Internet all day long, without giving it a thought to whose attachments they’re opening, what sites they’re visiting. And that makes it easy for the bad guys.

Scott Pelley: So tell folks at home what they need to know.

James Comey: When someone sends you an email, they are knocking on your door. And when you open the attachment, without looking through the peephole to see who it is, you just opened the door and let a stranger into your life, where everything you care about is.

That Jim Comey — the guy worried about victims of computer crime — laid out the horrible things that can happen when criminals access all the data you’ve got on devices.

Scott Pelley: And what might that attachment do?

James Comey: Well, take over the computer, lock the computer, and then demand a ransom payment before it would unlock. Steal images from your system of your children or your, you know, or steal your banking information, take your entire life.

Now, victim-concerned Jim Comey seems to think we can avoid such vulnerability by educating people not to click on any attachment they might have. But of course, for the millions who have their cell phones stolen, they don’t even need to click on an attachment. The crooks will have all their victims’ data available in their hand.

Unless, of course, users have made that data inaccessible. One easy way to do that is by making easy encryption the default.

Victim-concerned Jim Comey might offer 60 Minute viewers two pieces of advice: be careful of what you click on, and encrypt those devices that you carry with you — at risk of being lost or stolen — all the time.

Of course, that would set off a pretty intense fight with fear-monger Comey, the guy showing up to Brookings today to argue Apple’s customers shouldn’t have this common sense protection.

That would be a debate I’d enjoy Ben Wittes trying to debate.