When Your Lawyer is Acting Like H.R. Haldeman, It’s Time to Get a New Lawyer

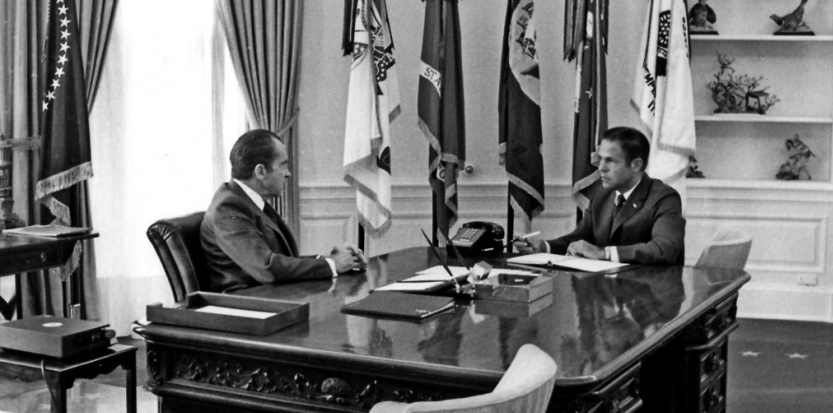

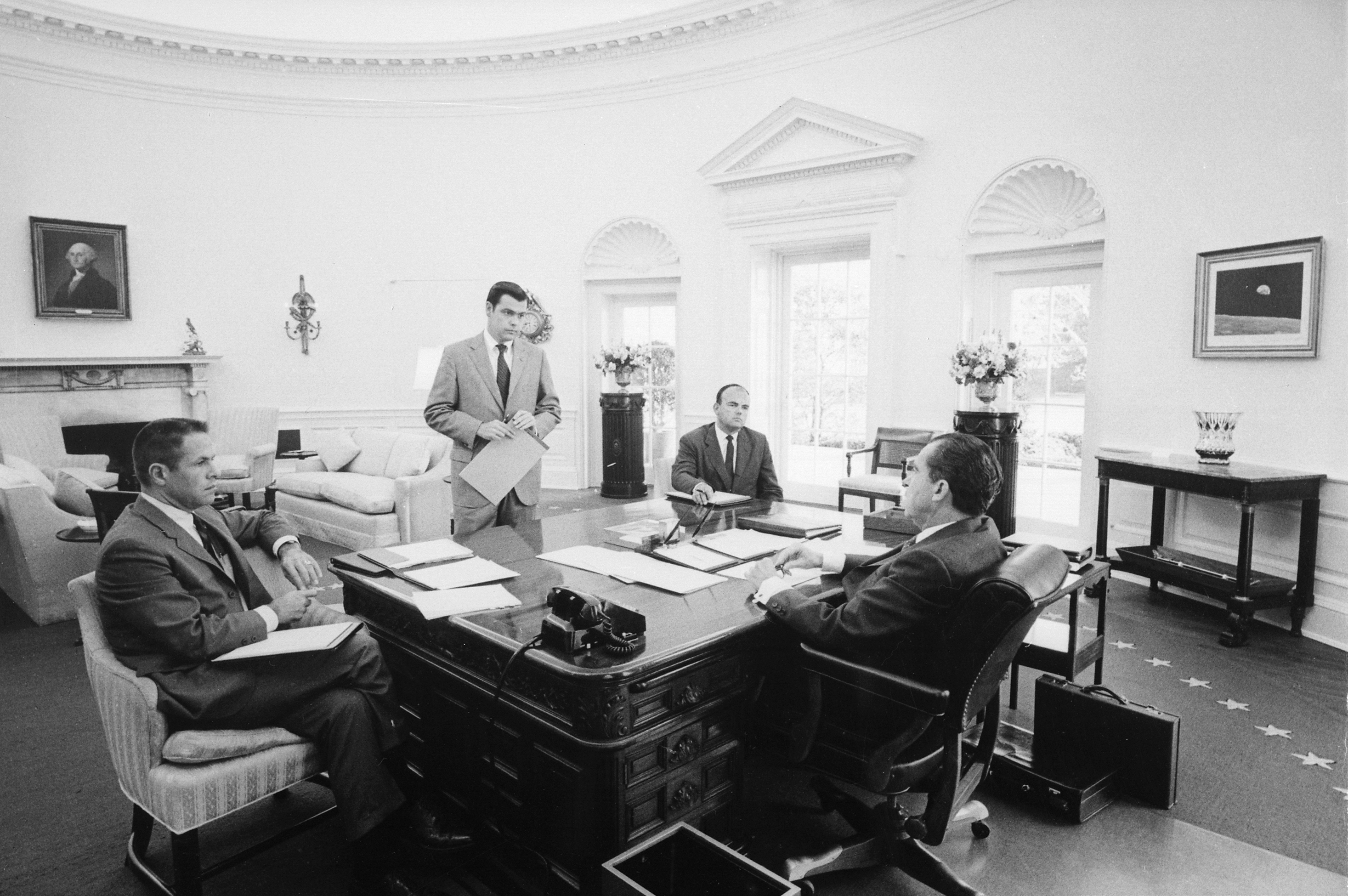

President Richard Nixon and his Chief of Staff HR Haldeman, before Nixon resigned in disgrace and Haldeman went to prison for 18 months after being convicted of perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice.

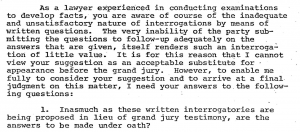

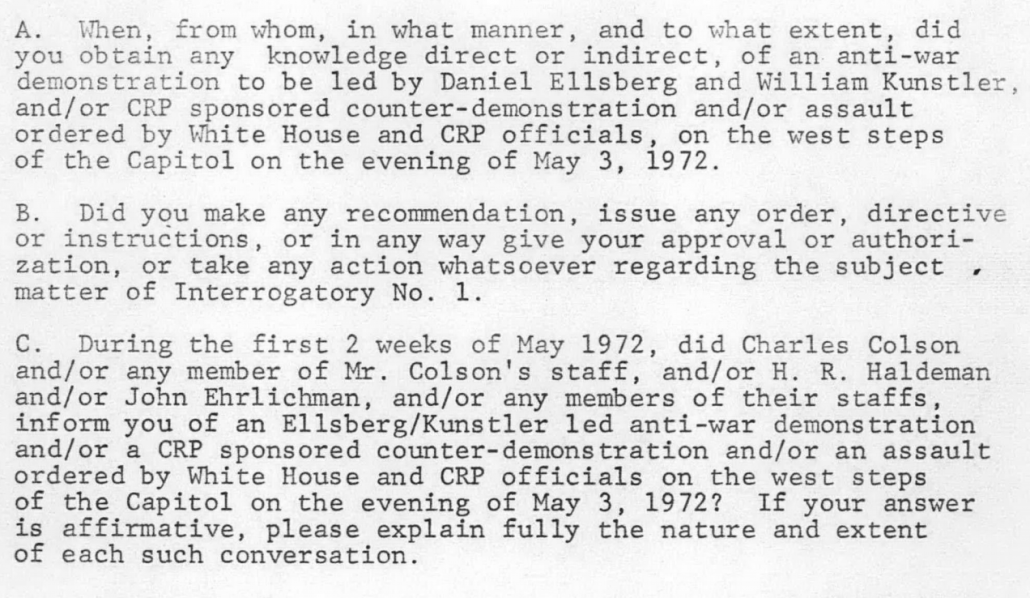

When Cassidy Hutchinson’s September 14, 2022 testimony to the J6 committee first came out, I remember being struck by three sentences in bold below (emphasis added) as I read it (from p. 48):

Ms. Hutchinson. And then just, at the end of that meeting, we had — because I had asked him about doing the, like, mock question preparation, and he said, “No.” So said, “Well, do you recommend anything that I can do to prepare for next week?” He’s like, “Get a good night’s sleep,” like, a few wishy-washy things.

And he said, “Don’t read anything about this on the internet.” He said, “Again, Cass, like, just trust me on this. I’m your lawyer. I know what’s best for you. The less you remember, the better. Don’t read anything to try to jog your memory. Don’t try to put together timelines.”

And he was like, “Especially if you put together timelines, we have to give those over to the committee. So anything you produce we have to give over to the committee. So l really” — he was like, “You can have things in front of you, but really don’t want you to, because we have to give that to the committee.”

So now I’m like, oh now I’m kind of scared. — Like, what if I want notes in front of me and he gets mad at me because I have to give them to the committee now? I didn’t know I would have to give them to the committee, but he told me I did, and he was my lawyer, so I was trying to trust him.

This wasn’t the only place in the transcript where words like these were used – they were almost a refrain. “Where have I heard this before?” I asked myself, then kept reading. Over this past weekend, while helping my mom clean out some old magazines, the penny dropped.

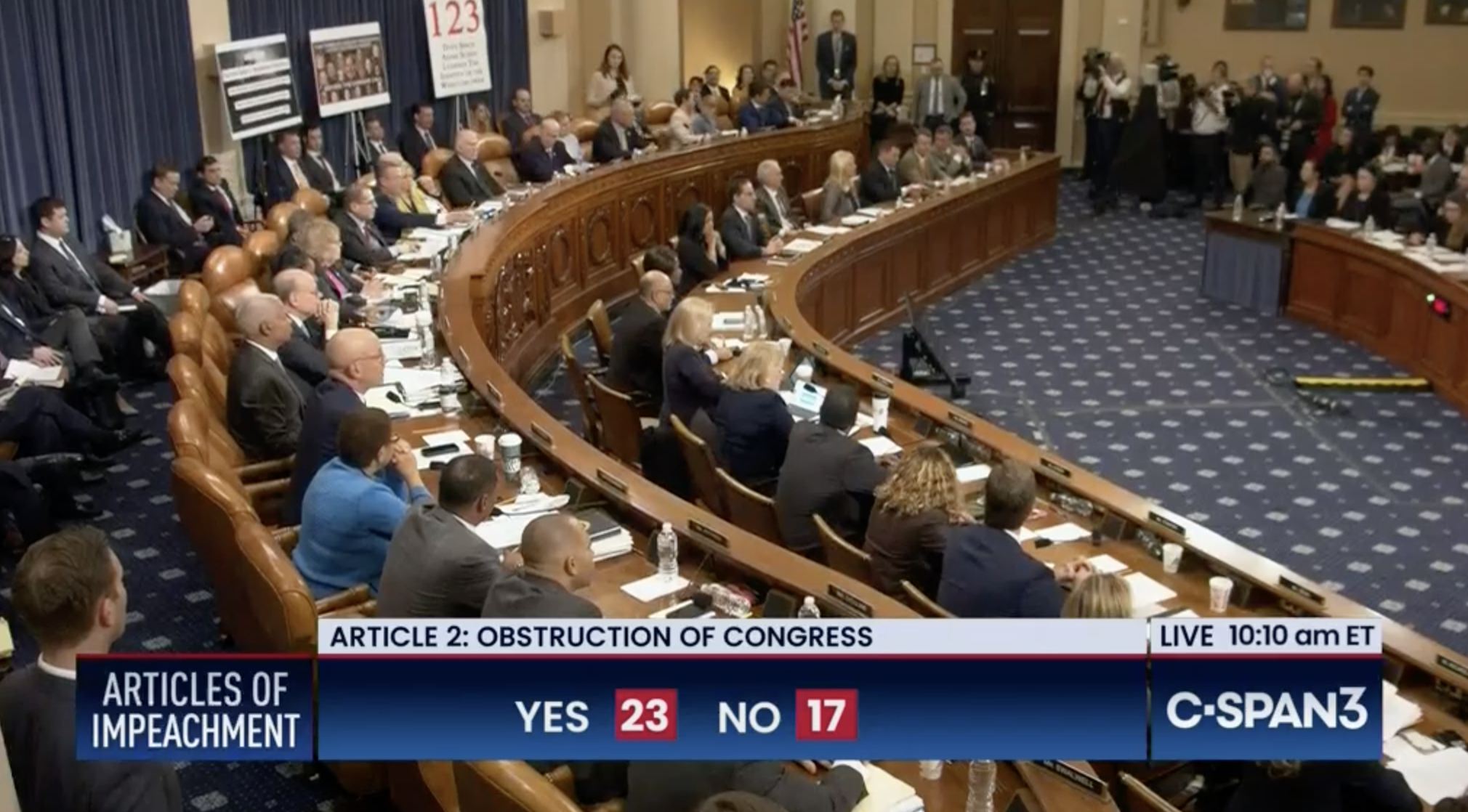

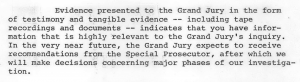

The date was March 21, 1974 1973 [corrected] – two days before the scheduled sentencing of the convicted Watergate burglars. At the White House, things were tense, as the scandal was growing and the coverup was in the process of unraveling. President Nixon, Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, and White House Counsel John Dean met for almost two hours, taking stock of the mess and looking for possible routes forward. They discussed additional payments to keep people quiet (noting that earlier payments had bought them silence through the 1972 election), and tried to figure out how to sideline the recently formed Senate Watergate committee chaired by Sen. Sam Ervin (D-NC).

Toward the end of the meeting, Nixon brought up a suggestion from his Domestic Policy Advisor (and former White House Counsel) John Ehrlichman: instead of letting the Ervin committee run riot in public, announce that all this was going to a new grand jury. From the transcript of the Nixon tapes (with all the typos, punctuation, etc. in the original, but with emphasis added):

PRESIDENT: John Ehrlichman, of course, has raised the point of another grand jury. I just don’t know how you’re going to do it. On what basis. I, I could call for it, but I…

DEAN: That would be, I would think, uh…

PRESIDENT: The President takes the leadership and says, Now, in view of all this, uh, stripped land and so forth, I understand this, but I, I think I want another grand jury proceeding and, and we’ll have the White House appear before them.” Is that right John?

p. 89 [sic, should be 88]

DEAN: Uh huh.

PRESIDENT: That’s the point you see. That would make the difference. (Noise banging on desk) I want everybody in the White House called. And that, that gives you the, a reason not to have to go up before the (unintelligible) Committee. It puts it in a, in an executive session in a sense.

HALDEMAN: Right.

PRESIDENT: Right.

DEAN: Uh, well…

HALDEMAN: And there’d be some rules of evidence. aren’t there?

DEAN: There are rules of evidence.

PRESIDENT: Both evidence and you have lawyers a

HALDEMAN: So you are in a hell of a lot better position than you are up there.

DEAN: No, you can’t have a lawyer before a grand jury.

PRESIDENT: Oh, no. That’s right.

DEAN: You can’t have a lawyer before a grand Jury.

HALDEMAN: Okay, but you, but you, you do have rules of evidence. You can refuse to talk.

DEAN: You can take the Fifth Amendment.

PRESIDENT: That’s right. That’s right.

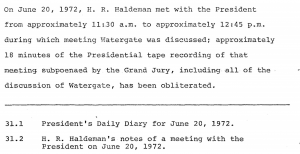

HALDEMAN: You can say you forgot, too, can’t you?

DEAN: Sure. –

PRESIDENT: That’s right.

p. 89

DEAN: But you can’t…you’re…very high risk in perjury situation.

PRESIDENT: That’s right. Just be damned sure you say I don’t…

HALDEMAN: Yeah…

PRESIDENT: remember; I can’t recall, I can’t give any honest, an answer to that that I can recall. But that’s it.

Hutchinson is too young to have lived through Watergate, but she clearly recognized that Stefan Passantino was acting more like he was more worried about someone else’s legal issues and not her own. It took her a while, but she eventually punted him and found a legal team who agreed to work on her behalf.

Passantino was clearly channeling his inner Haldeman when he told Cassidy Hutchinson “The less you remember, the better.”

Maybe this is a new entry in the DC book of Proverbs: “When your lawyer is acting like H.R. Haldeman, it’s time to get a new lawyer.”