About 70% of the way through the House Judiciary Committee interview of former Pittsburgh US Attorney Scott Brady on October 23, he explained how reaching out to FBI’s legal attaché in Ukraine to ask that Legat to reach out to Ukraine’s Prosecutor General fit within the scope of a project Bill Barr had assigned him.

Brady had described the project, hours earlier, as vetting incoming information on Ukrainian corruption received from the public, including but not limited to, Rudy Giuliani, using public information.

[W]e were to take information provided by the public, including Mayor Giuliani, relating to Ukrainian corruption. We were to vet that, and that was how we described it internally, a vetting process.

We did not have a grand jury. We did not have the tools available to us that a grand jury would have, so we couldn’t compel testimony. We couldn’t subpoena bank records.

But we were to assess the credibility of information, and anything that we felt was credible or had indicia of credibility, we were then to provide to the offices that had predicated grand jury investigations that were ongoing.

Brady distinguished between reaching out directly to Ukrainian investigators, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine or the Prosecutor General’s Office, and reaching out via the FBI.

The latter, Brady said, was,

a discreet, nonpublic way of securing information about these cases, including from publicly available documents or dockets, in a way that then wouldn’t, you know raise a flag and make the Ukrainian media, the national media aware? Because we were very concerned– [my emphasis]

“So ‘discreet’ here,” a Democratic staffer clarified, “means quietly, basically. You could do that quietly. Is that fair to say?”

“Yes,” Brady agreed, “quietly, as an investigation is…”

The Democratic staffer interjected, “Okay.”

“Usually conducted,” Brady finished, perhaps recognizing what he had just conceded.

Scott Brady’s misreading of discrete words

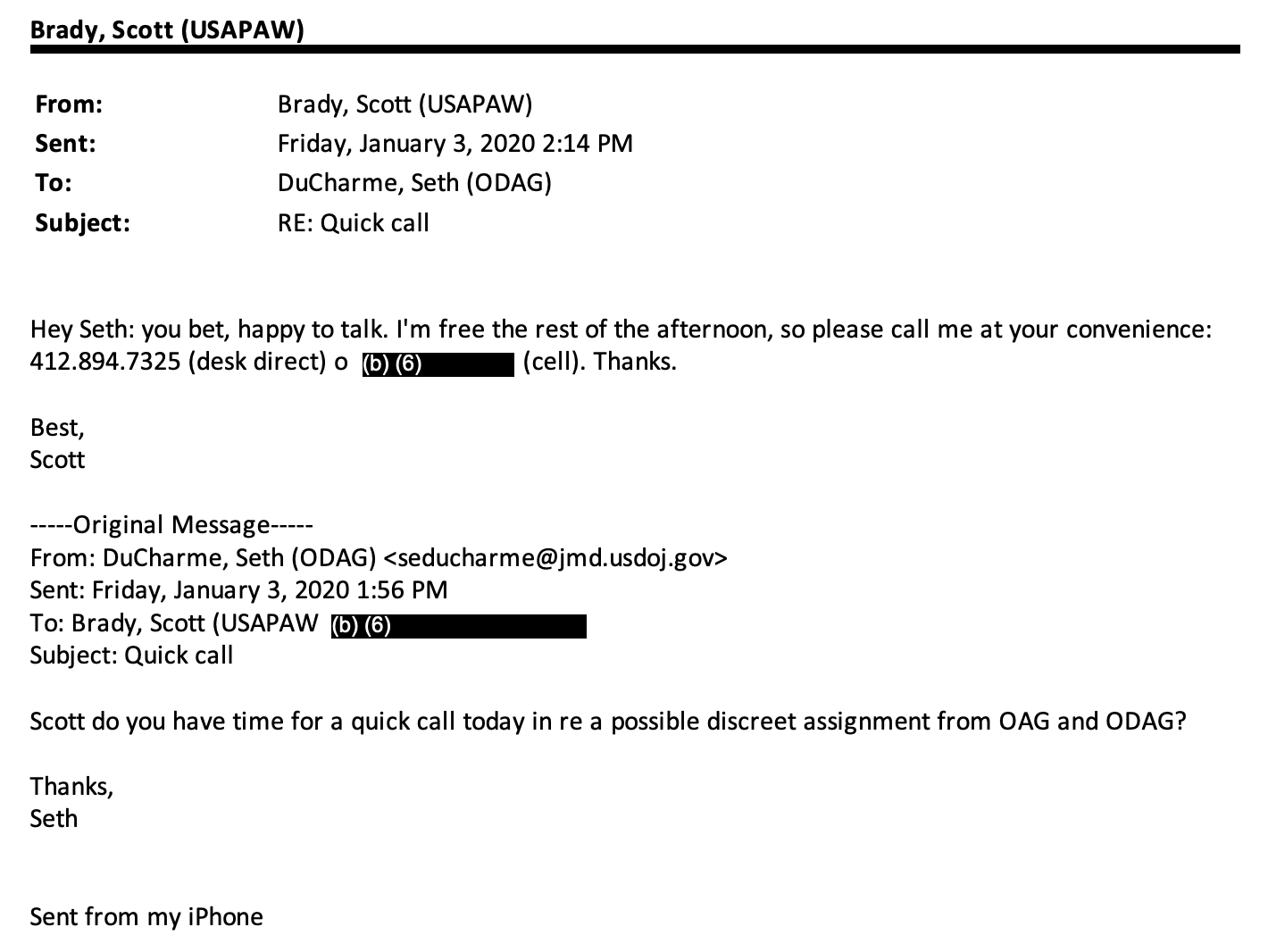

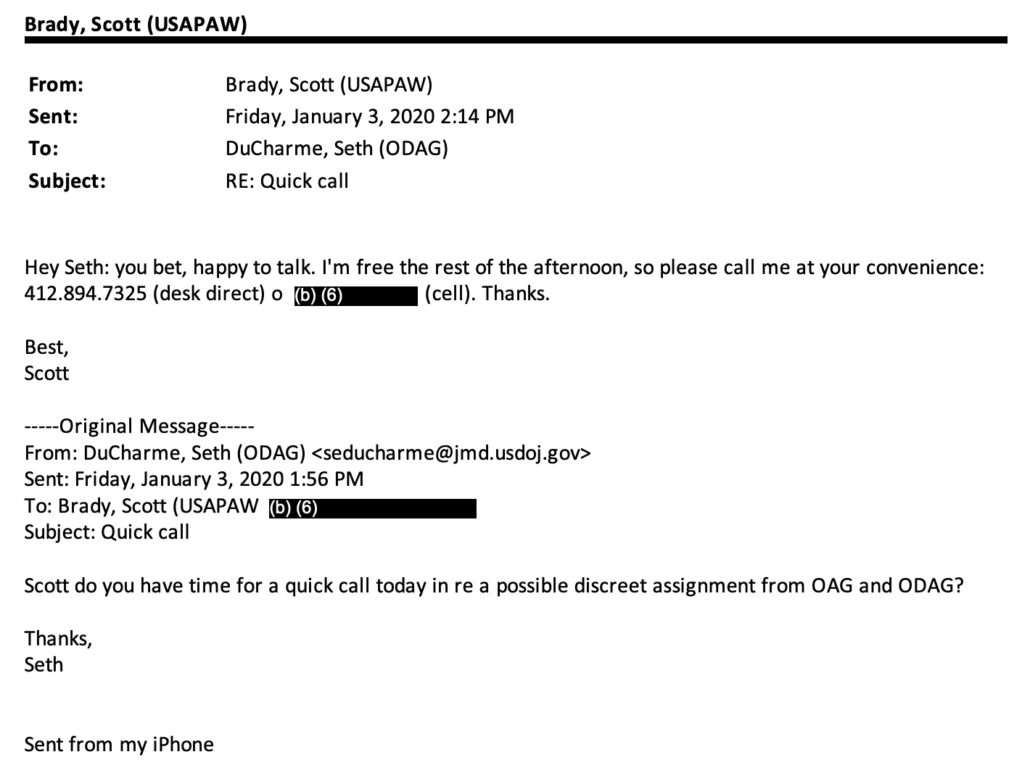

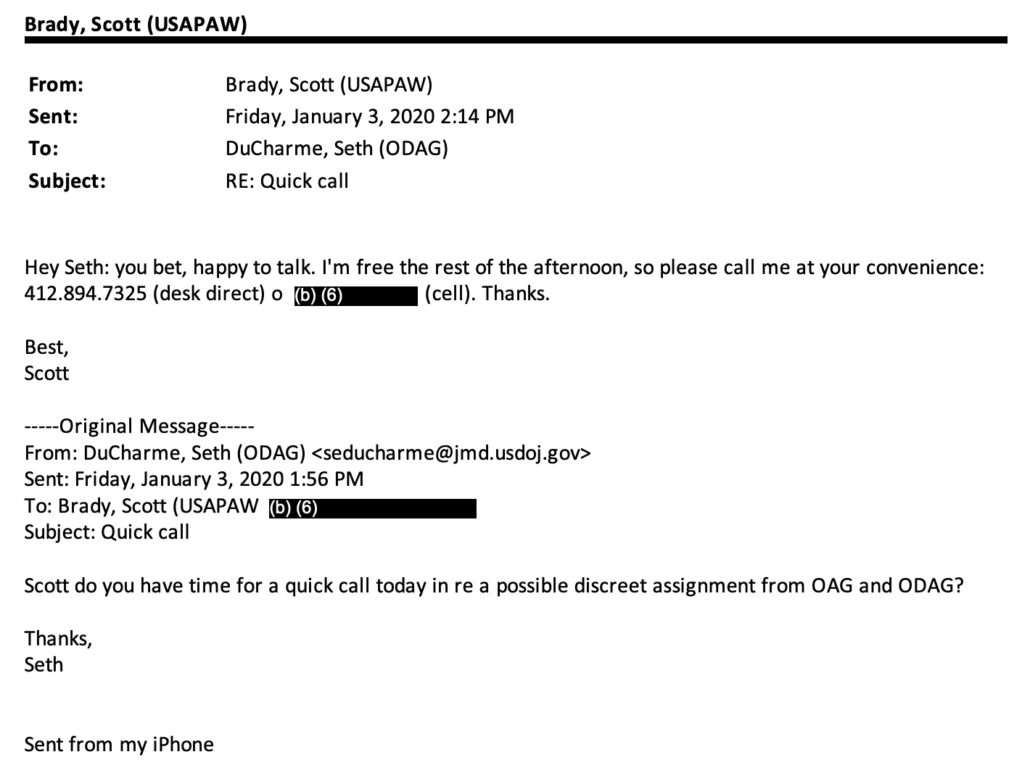

Two hours earlier, the same Democratic staffer had walked Brady through the email — one he himself had raised — via which a top Bill Barr aide, Seth DuCharme, had first given Brady his assignment on January 3, 2020.

DuCharme had given Brady that assignment between the time on, December 18, 2019, that the House had impeached Donald Trump for (among other things) asking President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to help Rudy Giuliani and Bill Barr look into the Bidens and Burisma, and the time, on February 5, 2020, that the Senate acquitted Trump.

The staffer asked Brady, close to the beginning of the Democrats’ first round of questioning in the deposition, what he took DuCharme to mean by the word, “discreet.”

In spite of the fact that both the staffer and Brady had that email in front of them, an email which spelled discreet, “d-i-s-c-r-e-e-t,” Brady tried to claim that by that, DuCharme meant to give Brady a discrete, “d-i-s-c-r-e-t-e” assignment.

Q And Mr. DuCharme refers to your assignment as a, quote, “discreet assignment,” correct?

A Yes. And I think what he meant by “discreet” was limited in scope and duration.

Q Oh, “discreet” means limited in this case?

A My understanding was that it was “discrete” meaning limited in scope and duration.

Q Okay. Did you think in any way that he was implying that it ought to be kept out of the public, this assignment?

Brady denied that this reference, “d-i-s-c-r-e-e-t,” meant Barr and DuCharme were trying to keep this project quiet, because after all, Bill Barr spoke of it publicly.

A No. I no, because, on the one hand, the Attorney General was speaking publicly of the assignment. However, it should be kept secret, to use your words, just as any investigation would be, any process would be that whether vetting or an investigation between the U.S. attorney’s Office and the FBI or any Federal agency.

Q You mean the information itself that you were discussing or coming upon in the investigation, that should be kept discreet or out of the public eye?

A The investigation, the process, all of that none of that is public

Q Got it.

A when we do that.

The staffer asked whether Brady really meant that Barr was discussing the assignment publicly on January 3, 2020, a month before Lindsey Graham first revealed — days after the Senate had acquitted Trump — that Barr had, “created a process that Rudy could give information and they would see if it’s verified.”

Q And you indicated that you believe that the Attorney General at that time was discussing your assignment publicly? Is that in your recollection, was he doing that publicly on January 3, 2020?

A No. I mean subsequent comments.

Q Okay. So, after it became known that this investigation or assignment had been given to you, Attorney General Barr did make public comments. Is that right?

A Yes.

That gives you some sense of the level of candor that Pittsburgh’s former top federal law enforcement officer, Scott Brady, offered in this testimony. About the most basic topic — how he came to be given this assignment in the first place — he offered two bullshit claims in quick succession, bullshit claims that attempted to downplay the sketchiness of how he came to be assigned a task intimately related to impeachment right in the middle of impeachment.

The word games about “d-i-s-c-r-e-e-t” are all the more cynical given that American Oversight, whose FOIA Brady repeatedly described having read (probably as a way to prepare for the deposition), titled their page on the it “A Possible Discreet Assignment.”

The high risk of deposing Scott Brady

Inviting Scott Brady to testify to the House Judiciary Committee was a high risk, high reward proposition for Jim Jordan.

Brady, if he could hold up under a non-public deposition, might give the Republicans’ own impeachment effort some credibility — at least more credibility than the debunked, disgruntled IRS agents and indicted fugitives that the project had relied on up to this point.

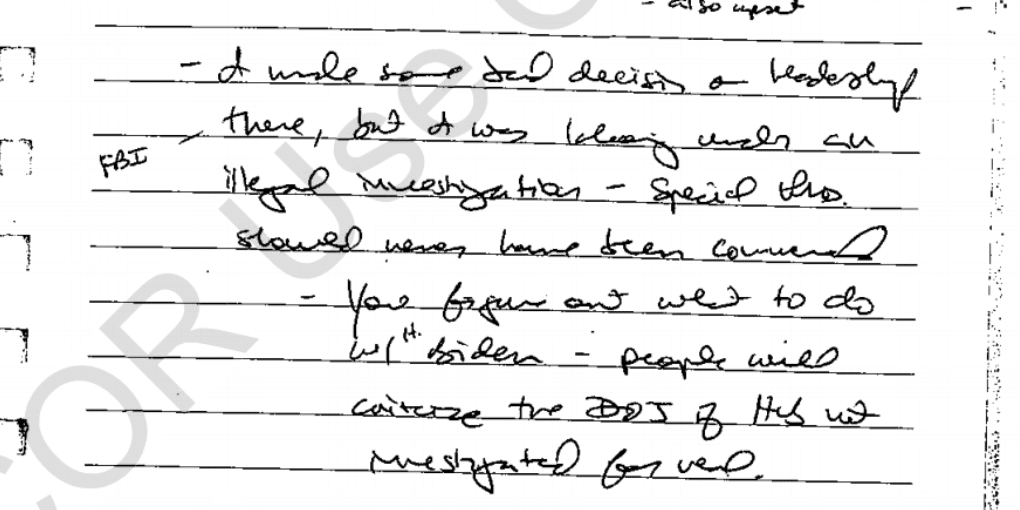

Sure enough, in the wake of his testimony, the usual propagandists have frothed wildly at Brady’s descriptions of how he faced unrelenting pushback as he pursued a project ordered by the Attorney General and “fully support[ed]” by the top management of the FBI. Poor Scott Brady, the right wing wailed, struggled to accomplish his task, even with Bill Barr, Jeffrey Rosen, Chris Wray, and David Bowdich pulling for him.

The right wing propagandists didn’t need the least bit of logic. They needed only a warm body who was willing to repeat vague accusations, including (as Brady, a highly experienced lawyer who should know better did more than once), parroting public claims, usually Gary Shapley’s, about which he had no firsthand knowledge as if he knew them to be fact.

But testifying before House Judiciary also meant being interviewed by staffers of the guy, Jerry Nadler, who first raised concerns about the project after Lindsey blabbed about it. In real time, Nadler established that Bill Barr’s DOJ had set up Brady to ingest material from Rudy Giuliani, then put the US Attorney in EDNY (at the time, Richard Donoghue, but Donoghue would swap places with DuCharme in July 2020) in charge of gate-keeping several investigations into Ukraine. Geoffrey Berman, the US Attorney in SDNY whom Barr fired in June 2020 in an attempt to shut things down, would later reveal that this gate-keeping effort had the effect of limiting SDNY’s investigation into Rudy’s suspected undisclosed role as an agent of Ukraine.

That part has become public: Freeze the investigation into whether Rudy is a foreign agent in SDNY, move any investigation into identified Russian asset Andrii Derkach to EDNY and so away from the Rudy investigation, and set up Scott Brady in WDPA to ingest the material Rudy collected after chumming around with Derkach and others.

What had remained obscure, though, was the role that Brady had with respect to that other “matter[ that] that potentially relate[s] to Ukraine:” the Hunter Biden investigation in Delaware. Indeed, DOJ’s letter to Nadler about it falsely suggested all covered matters were public. It turns out Stephen Boyd, who wrote the letter, was being “discreet” about there being another investigation, the one targeting Joe Biden’s son.

Inviting Scott Brady to a deposition before the House Judiciary Committee as part of an effort to fabricate an impeachment against Joe Biden provided the the same congressional office that first disclosed this corrupt scheme an opportunity to unpack that aspect of it.

It turns out Jerry Nadler’s staffers were undeterred by shoddy word games about the meaning of, “d-i-s-c-r-e-e-t.”

The virgin birth of a “Hunter Biden” “Burisma” search

The central focus of the HJC interview, unsurprisingly, was how an informant came to be reinterviewed in June 2020 about interactions he had with Burisma’s Mykola Zlochevsky months and years earlier, the genesis of the FD-1023 on which Republicans are pinning much of their impeachment hopes, and how and on what terms that FD-1023 got forwarded to David Weiss, who was already investigating Hunter Biden.

Yet it took three rounds of questioning — Republicans then Democrats then Republicans again — before Brady first explained how his team, made up of two AUSAs working full time, himself, two other top staffers, and an FBI team, came to discover a single line in a 3-year old informant report. With Republicans, Brady described that it came from a search on “Hunter Biden” and “Burisma.”

Q And the original FD1023 that you’re referring as information was mentioned about Hunter Bidden and the board of Burisma, how did that information come to your office?

A At a high level, we had asked the FBI to look through their files for any information again, limited scope, right? And by “limited,” I mean, no grand jury tools. So one of the things we could do was ask the FBI to identify certain things that was information brought to us. One was just asking to search their files for Burisma, instances of Burisma or Hunter Biden. That 1023 was identified because of that discreet statement that just identified Hunter Biden serving on the Burisma board. That was in a file in the Washington Field Office. And so, once we identified that, we asked to see that 1023. That’s when we made the determination and the request to reinterview the CHS and led to this 1023. [my emphasis]

That answer — which described Brady’s team randomly deciding to search non-public information for precisely the thing Trump had demanded from Volodymyr Zelenskyy less than a year earlier — satisfied Republican staffers. Again, they weren’t looking for logical answers, much less rooting out Republican corruption; they needed a warm body who might be more credible than Gal Luft.

It took yet another round of questions before the Democrats asked Brady why, if his job was to search public sources, he came to be searching 3-year old informant reports for mentions of Hunter Biden. At that point, the search terms used to discover this informant report came to shift in Brady’s memory, this time to focus on Zlochevsky, not Hunter Biden personally.

Q Okay. And so, in the actually, in the first and second hours, you said pretty extensively that your role was to vet information provided from the public, correct?

A Correct.

Q And so the 1023, the original 1023, was not information provided from the public, correct?

A That’s correct

Q Okay.

A yes.

Q But it came up because you’d received information from Mr. Giuliani and, in your vetting of that information, you ran a search?

A Correct.

Q Okay.

A And just to clarify, I don’t remember if we asked the FBI to search for “Burisma”

Q Right.

A or “Zlochevsky.”

Q Understood.

Searching on “Zlochevsky” and “Burisma” wouldn’t have gotten you to the specific line in a 2017 FD-1023 about Hunter Biden — at least not without a lot of work. Chuck Grassley revealed the underlying informant report came from a 3-year long Foreign Corrupt Practices Act investigation into Zlochevsky that had been closed in December 2019.

December 2019.

Remember that date.

Finding that one line about Hunter Biden in a 3-year investigative file would have been the quintessential needle in a haystack.

Spying on the twin investigations

Perhaps this is a good time to explain a totally new — and alarming — detail disclosed in this deposition.

Scott Brady didn’t just accept information from the public, meaning Rudy, and then claim to vet it before handing it on to other investigations. Brady didn’t just attempt to contact Ukraine’s Prosecutor General — through the Legat and therefore discreetly — to try to get the same cooperation that Trump had demanded on his call with Zelenskyy.

He also quizzed the investigators.

In the guise of figuring out whether open grand jury investigations already had the information he was examining, he asked them what they were doing.

In Geoffrey Berman’s case, this involved an exchange in which Scott Brady — the guy claiming to be working off public files and leads from Rudy — told Berman — the guy with a grand jury investigating Rudy — that Berman was wrong.

Q Okay. Let me be more specific. At some point, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Mr. Berman, wrote you a letter or email that provided information he thought that you should have because of the material that he knew you were reviewing, that he thought might be inconsistent with what you were finding; is that correct?

A That’s correct. And then we wrote him an letter back saying that some of the contents in his letter was incorrect.

Q Okay. So you had some kind of dispute with Mr. Berman about the information that they had versus the information that you had, the subject had seemed inconsistent. Is that fair to say?

A I think there was a clarification process that was important that we shared information and made sure that they especially had an understanding because they had a predicated grand jury investigation, what was in our estimation and our limited purview correct and incorrect. So we wanted to make sure they had the correct information. [my emphasis]

As we’ll see, this is important — nay, batshit crazy — based on what the full sweep of Brady’s deposition revealed about his interactions with Rudy. Because, as Brady conceded by the end of the interview, Rudy probably wasn’t entirely forthcoming in an interview Brady did with Rudy.

But, as described, it doesn’t seem all that intrusive.

In David Weiss’ case, however, Brady described that, after Hunter Biden’s prosecutors refused to tell him what they were up to and he intervened with Weiss himself, using “colorful language,” the Hunter Biden team instructed Brady to put his questions in writing.

Q Okay. And so the I think you said you passed along or, not you personally, but your office passed along interrogatories or questions for them.

A That’s right.

Q That was along the lines of asking them what steps they had taken. Is that fair to say?

A Some limited steps. Correct.

Q Okay. So you were asking them about their investigation to help inform your investigation.

A Yes, to help focus our process so that we weren’t doing anything that, as I mentioned, would be duplicative or would complicate their investigation in any way.

[snip]

Q Okay. And you wanted to know that because you didn’t want to start doing the same investigative steps that they were doing?

A Correct.

Q But you indicated before that you didn’t have the power to get bank records, for example; is that right?

A Correct.

Q So was there a reason that you would need to know whether the other district had subpoenaed something if you weren’t able to subpoena bank records yourself?

A Yes. For example, if we were given a bank account number and wanted to see if they had already looked at that, we would want to know if they had visibility and say, you know: Here’s a bank account that we had received; have you, you know, have you subpoenaed these records, have you can you examine whether this bank account has sent funds into other Burisma-related accounts or Biden-related accounts?

Q So you were looking to sort of use their grand jury or subpoena authority to learn information because you didn’t have that tool in your own investigation?

A We weren’t really looking to learn information about their investigation. We just wanted to know if we needed to do anything with that, to try to corroborate it through perhaps other sources or through the FBI, or if we should even hand it over, again, if it was credible or not credible. If there is nothing to be gained, I don’t want to waste their time if they said: Oh, yeah, we’ve looked at that, and this bank account doesn’t show up anywhere in our records.

Q So, if you had some kind of information or question about a bank account, was there anything stopping you from just passing that onto Delaware without asking them also to tell you whether they had received any information pursuant to a subpoena or any other lawful process?

A We could have, but that wasn’t my understanding of our assignment. Our understanding of the assignment was to really separate the wheat from the chaff and not waste their time with a dump of information, maybe, you know, a percentage of which would be credible or have indicia of credibility. So they have limited resources. They have, you know, a broad tasking. So we didn’t want to waste their time by doing that. We thought it would be more efficient to engage them, ask them: Have you seen this?

Yes, no. And then pass it on, make a determination of what to pass onto them.

Aside from the fact that this sounds like it took more time than simply sending a bunch of bank account numbers to allow the Delaware team to deduplicate — the FBI does have computers as it turns out, and one of the FBI’s best forensic accountants has worked on this investigation — the timing of this matters.

This happened in April and May 2020, so in the months and weeks before Brady’s team did a search on Hunter Biden and Burisma — or maybe it was Zlochevsky and Burisma — and found a 3-year old informant report mentioning the former Vice President’s son.

So Brady sent, and after some back-and-forth, got some interrogatories from Weiss’ team, and then the next month discovered an informant that Delaware presumably hadn’t chosen to reinterview.

“Do not answer” about the vetting

By the point when Brady described randomly searching on Hunter Biden and Burisma — or maybe it was Zlochevsky and Burisma — the former US Attorney had already repeatedly balked when asked if he had vetted anything pertaining to Zlochevsky.

The first time, his attorney, former Massachusetts US Attorney Andrew Lelling and so, like Brady, a former Trump appointee — I think this is the technical term — lost his shit, repeatedly instructing Brady not to answer a question that goes to basic questions about the claimed purpose for this project: vetting leads.

Q All right. The statements that are attributed to Mr. Zlochevsky, did you do any work, you or anyone on your team, to determine whether those statements are consistent or inconsistent with other statements made by Mr. Zlochevsky?

Mr. Lelling. He’s not going line by line from a 1023. He’s not discussing at that level of detail.

Q. Okay. Could you answer the question that I asked you though?

Mr. Lelling. No. Do not answer.

Q. That was not a line-by-line question.

Mr. Lelling. Do not answer the question. You picked the line. You read it. You were asking him

Q. That’s not no, I didn’t. What line did I read from?

Mr. Lelling. Okay. I’m being figurative.

Q. Okay. I’m asking

Mr. Lelling. He is not going to go detail by detail through the 1023.

Q. I’m not asking that. No, I’m not going to ask that. I am asking a general question about whether he tried to determine whether there were consistent or inconsistent statements made by one of the subsources, generally.

Mr. Lelling. Yeah. No. He can’t answer that. This is too much

Q. So we’re going to keep asking the questions I understand he may not want to answer. We’re going to keep asking the questions to make a record. If you decline to answer

Mr. Lelling. Sure. I understand. And some maybe he can. This is

Q. We’re going to keep asking the questions though.

Mr. Lelling. This is a blurry line, a

Q. Understood.

Mr. Lelling. deliberative process question. And I’m sort of making those judgments question by question. So, maybe, categorically, he can’t answer any of the questions you’re about to ask. Maybe he can. So

Q. Well, if you let me ask them, then we can have your response.

Mr. Lelling. Sure.

Q. Fair? Okay. So the subsource, Mr. Zlochevsky, did you make any effort in your investigation to look in public sources, for example, whether Mr. Zlochevsky had made statements inconsistent with those attributed to him by the CHS in the 1023?

Mr. Brady. I don’t remember. I don’t believe we did. I think what our broadly, without going into specifics, what we were looking to do was corroborate information that we could receive, you know, relating to travel, relating to the allegation of purchase of a North American oil and gas company during this period by Burisma for the amount that’s discussed in there. We used open sources and other information to try to make a credibility assessment, a limited credibility assessment. We did not interview any of the subsources, nor did we look at public statements by the subsources relating to what was contained in the 1023. We believed that that was best left to a U.S. attorney’s office with a predicated grand jury investigation to take further.

Brady’s team looked up whether Burisma really considered oil and gas purchases at the time. They looked up the informant’s travel. But did nothing to vet whether Zlochevsky’s known public statements were consistent with what he said to the informant.

Democrats returned to Brady’s description of how he had vetted things, including the FD-1023, later in that round. He was more clear this time that while his team checked the informant’s travel and while he repeatedly described his vetting role as including searching public news articles, his team never actually checked any public news articles to vet what the 1023 recorded about Zlochevsky’s claims.

Q Okay. But open source so, other than witness interviews, you did do some open source or your team did some open source review to attempt to corroborate some of what was in the 1023? Is that fair?

A Just limited to the 1023?

Q Well, let’s start with that.

A Yes.

Q Okay. And what does that generally involve, in terms of the open source investigation?

A It could be looking at it could be looking at public financial filings. It could be looking at news articles. It could be looking at foreign reporting as well, having that translated. Anything that is not within a government file would be open source, and it could be from any number of any number of sources.

Q So, when you look at news reports, for example, would you note if there was a witness referred to in the 1023 that had made a statement that was reported in the news article, for example? Would that be of note to your investigators?

A Relating to the 1023? No. We had a more limited focus, because we felt that it was more important to do what we could with certain of the information and then pass it on to the District of Delaware, because then they could not only use other grand jury tools that were available but, also, we didn’t have visibility into what they had already investigated, what they had already done with Mr. Zlochevsky, with any of the individuals named in this CHS report. [my emphasis]

Scott Brady claimed to search news reports, even in foreign languages. But did not do so about the matter at the core of his value to the GOP impeachment crusade because, he claimed, his team had no visibility into what the Delaware team had already done with Zlochevsky.

Only they did have visibility: they had those interrogatories they got in May.

Having been told by Brady that he didn’t bother to Google anything about what Zlochevsky had said publicly, Democratic staffers walked him through some articles that might have been pertinent to his inquiry, quoting one after another Ukranian saying there was no there there.

Only the claims in the June 4, 2020 article rang a bell for Brady at all, though he did say the others may have made it into a report he submitted to Richard Donoghue (who by that point had swapped roles with DuCharme at Main DOJ) in September 2020.

But as to Brady? The guy who spent nine months purportedly vetting the dirt the President’s lawyer brought back from his Russian spy friends claims to have been aware of almost none of the public reporting on the matters Rudy pitched him. Which apparently didn’t stop him from calling Geoffrey Berman and telling Berman he knew better.

The open source that Scott Brady’s vetting team never opened

Even before they walked Brady through those articles, some appearing days before the informant reinterview, Democratic staffers raised Lev Parnas.

Was Brady familiar with the interview, conducted less than a year before his team reinterviewed the informant, that Parnas claimed Vitaly Pruss did with Zlochevsky on behalf of Rudy Giuliani, the one that had been shared with the House Intelligence Committee as part of impeachment?

Okay. And just to be clear, I think my colleague has already explained this, but this document was provided to investigators on the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in 2019, before your assessment began, in relation to the first impeachment inquiry of President Trump. But you indicated you were not aware that that evidence was in the record of that investigation?

A Correct.

[snip]

Q Okay. So you indicated you’ve never seen this document before. May I actually ask you, before we go through it: You, during the course of your investigation, you asked the FBI or directed others to ask the FBI to review their holdings for any information related to Burisma or Zlochevsky, correct?

A Yes. We asked them, for certain specific questions, to look in open source, as we talked about, and then to look in their investigative files to see if they had intersected with these names or, you know, this topic before.

Q Okay. And they yielded this 2017 1023 that then led you to interview the CHS, correct?

A Yes.

Q Okay. But you never asked, for example, the House Permanent Select Committee investigators or anyone associated with that investigation to do a similar inquiry for evidence relating to Zlochevsky?

A No, I don’t believe we did.

Q Okay. And, like you said, you were not aware that this interview had taken place in 2019. Is that fair to say?

A I don’t believe I was, no.

Q Okay. And anyone on your team, as far as you know, was not aware that Mr. Zlochevsky had been interviewed at the direction of Giuliani before your assessment began?

A I don’t believe so.

One of the Democratic staffers got Brady to agree that, yes, he had found a 3-year old informant report and tried to contact Ukraine’s Prosecutor General, discreetly, but hadn’t bothered to see whether there were relevant materials in the wealth of evidence and testimony submitted as part of the impeachment.

Q Okay. I guess my question was just more based on your own description of your own investigative efforts. I mean, you went on your own, on your own initiative, to search FBI records that had anything to do with Zlochevsky, correct?

A Correct.

Q Or Burisma, but you don’t know what the search term was.

A Correct. There were multiple, but yes. I can’t remember the specific one that uncovered the underlying 1023.

Q Okay. But you didn’t make a similar effort to search the impeachment investigative files that were released and public at that time and dealing with the same matter. Is that

A Correct. To my knowledge, yes

Q Okay.

A that’s correct.

As Brady described, the team he put together to carry out a task assigned during impeachment that closely related to the subject of impeachment, “we were certainly aware” of the ongoing impeachment, but, “I don’t believe that our team looked into the record.”

Brady, at various times, also excused himself from anything pertaining to Lev Parnas because Rudy’s former associate had been indicted.

Mr. Brady. So, just to clarify, without going into detail, because Mr. Parnas had been indicted by SDNY, we didn’t develop any information relating to Mr. Parnas that either Mr. Giuliani gave us or that we received from the public, and we felt that it was best handled by SDNY, since they had that full investigation.

[snip]

[W]e cordoned that off as an SDNY matter. So, any information that we received from Mr. Giuliani, for example, relating to Mr. Parnas, we relayed to SDNY.

In the same way that the scheme Barr set up to gatekeep Ukraine investigations meant SDNY wouldn’t look at Andrii Derkach, because that had been sent to EDNY, Scott Brady wasn’t going to look at Lev Parnas, because he was sending that to SDNY.

That’s important backstory to the FD-1023 being sent to Delaware as if it had been vetted.

The things Rudy didn’t tell Scott Brady

It matters not just because it exhibits Brady’s utter failure to do what he claimed the task was: using open source information to vet material (which does not rule out that his team performed some other task exceptionally well). It matters because, Brady claims, Rudy didn’t tell him any of this.

One of the minor pieces of news in the Scott Brady interview came in an email that Brady and DuCharme exchanged about interviewing Rudy that probably should have — but, like other responsive records, appears not to have been — released to American Oversight in its FOIA.

Q And I’ll get copies for everyone. It’s very short. This is an email from Seth DuCharme to you, subject: “Interview.” The date is Wednesday, January 15, 2020. And, for the record, the text of the email is, quote, “Scott I concur with your proposal to interview the person we talked about would feel more comfortable if you participated so we get a sense of what’s coming out of it. We can talk further when convenient for you. Best, Seth.” And tell me if you recall that email.

A Yes, I do recall it.

Q Okay. And the date, again, is January 15, 2020, correct?

A That’s right.

Q So that was 14 days before the interview that you just described at which you were present, correct?

A Correct.

Q Does that help you recall whether this email between you and Seth DuCharme was referring to the witness that you participated in the interview of on January 29, 2020?

A Yes, it definitely did.

Q Okay. Just for clarity, yes, this email is about that witness?

A Yes, that email is about setting up a meeting and interview of Mr. Giuliani.

Q Okay. So the witness was Mr. Giuliani? That’s who you’re talking about?

A Yes.

Neither the date of this interview nor Brady’s participation in it is new. After the FBI seized his devices, Rudy attempted to use the interview to claim he had been cooperating in law enforcement and so couldn’t have violated FARA laws. And NYT provided more details on the interview in the most substantive reporting to date on Brady’s review, reporting that conflicts wildly with Brady’s congressional testimony.

The new detail in the email — besides that DuCharme didn’t mention Rudy by name (elsewhere Brady explained that all his “discrete” communications with DuCharme were face-to-face which would make them “discreet”) or that the email was written two days before Jeffrey Rosen set up EDNY as a gate-keeper — is DuCharme’s comment that “we” would be more comfortable if Brady participated so “we” got a sense of what was coming out of it.

I don’t want to take this away from you, because I know you and I

A Oh, sure.

Q just have one copy. But just, again, what this email says is, “I concur with your proposal to interview the person we talked about.” And then he says, “Would feel more comfortable if you participated so we get a sense of what’s coming out of it.” Do you see that?

A Uhhuh.

Q Okay.

A Yes.

Q So what did he mean by “we”? Who was he referring to by “we”? Do you know?

A I don’t know.

Q Okay. Is it fair to infer that he is referring to the Attorney General and the Office of the Deputy Attorney General where he was working?

A I don’t know. Yeah, some group of people at Main Justice, but I don’t know specifically if it was DAG Rosen, Attorney General Barr, or the people that were supporting them in ODAG and OAG.

Q Okay. But they wanted to, quote, “get a sense of what’s coming out of it,” correct? A

From the email, yes.

Scott Brady was supposed to vet Rudy, not just vet the dirt that Rudy shared with him.

And on that, if we can believe Brady’s testimony, Brady failed.

As Democratic staffers probed at the end of their discussion on the Parnas materials from impeachment, it was not just that Brady’s own team didn’t consult any impeachment materials, it’s also that Rudy, when he met with Brady on January 29, 2020, didn’t tell Brady that he had solicited an interview in which Zlochevsky had said something different than he did to the informant.

Q Okay. Then the other question I think that I have to ask about this is: This is a prior inconsistent statement of Mr. Zlochevsky that your investigation did not uncover, but it’s a statement that Mr. Giuliani was certainly aware of. Would you agree?

A Yes, if based on your representation, yes, absolutely.

Democratic staffers returned to that line of questioning close to the end of the roughly 6-hour deposition. After Republicans, including Jim Jordan personally, got Brady to explain that he was surprised by the NYPost story revealing that Rudy had the “laptop” on October 14, 2020, Democratic staffers turned to a Daily Beast article, published three days after the first “Hunter Biden” “laptop” story, quoting Rudy as saying, “The chance that [Andrii] Derkach is a Russian spy is no better than 50/50” and opining that it “Wouldn’t matter” if the laptop he was pitching had some tie to the GRU’s hack of Burisma in later 2019.”What’s the difference?”

Using that article recording Rudy’s recklessness about getting dirt from Russian spies, a Democratic staffer asked if Brady was surprised that Rudy hadn’t given him the laptop. Brady’s attorney and former colleague as a Trump US Attorney (and, as partners at Jones Day), Lelling, intervened again.

Q So when you said earlier that you were surprised you hadn’t seen the laptop, were you surprised that Mr. Giuliani didn’t produce it to you?

A Yes

Q And why is that.

Mr. Lelling. I don’t think you can go into that. You can say you were surprised.

Q You can’t tell us why you were surprised?

Mr. Lelling. He can’t characterize his rationale for his surprise. That’s correct.

Q Why is that? Just for the record, what is the reason?

Mr. Lelling. Because it gets too close to deliberative process concerns that the Department has.

Q It’s deliberative process to explain why he was surprised that Giuliani didn’t give him something that Giuliani said he had public access to?

Mr. Lelling. Correct.

Then Democrats returned, again, to Lev Parnas’ explanation of how Vitaly Pruss had interviewed Zlochevsky, this time using this October 24, 2020 Politico story as a cue. Democrats asked Brady if he was aware that, eight months before the vetting task started, Rudy had heard about laptops being offered.

Okay. And what I am asking you is, have you ever heard that during the course of your investigation that Mr. Giuliani actually learned of the hard drive material on May 30th, 2019?

A No, not during our 2020 vetting process, no.

Q Mr. Giuliani never shared anything about the hard drives or the laptop or any of that in his material with you?

Mr. Lelling. Don’t answer that.

Q Oh, you are not going to answer?

Mr. Lelling. I instruct him not to answer.

Q. He did answer earlier that the hard drive. That Mr. Giuliani did not provide a hard drive.

Mr. Lelling. Okay.

Mr. Brady. He did not provide it. We were unaware of it.

Then Democrats explored Parnas’ claim in the Politico story that Zlochevsky said he’d provide dirt, if Rudy helped him curry favor with DOJ (note, the staffers misattributed a statement about extradition in the article, which pertained to Dmitry Firtash’s demand, to Zlochevsky). When they asked Brady if he knew that Zlochevsky had reason to curry favor with DOJ because was accused of money laundering, Brady first pointed to two other jurisdictions where such investigations were public, then asked for legal advice and was advised not to respond.

Q Okay. And according to the article Pr[u]ss told Giuliani at the May 30th, 2019, meeting that Mr. Zlochevsky had stated that he had, quote, “derogatory information about Biden, and he was willing to share it with Giuliani if Giuliani would help Zlochevsky, ‘curry favor with the Department of Justice and help him with an extradition request or other efforts by DOJ to investigate or prosecute Zlochevsky.'” Do you see that allegation in the report?

A I see the first part, I’m sorry. I don’t see the extradition.

Q Okay. So what it says in the article is that Zlochevsky was interested in currying favor with the Department of Justice, correct?

A Yes.

Q Are you aware that Mr. Zlochevsky was accused of money laundering among other financial crimes?

A I’m sorry, by which jurisdiction? I’m aware that there were allegations regarding potential money laundering and Mr. Zlochevsky that were investigated by the U.K. and by Ukrainian prosecutors. Could I just have one second?

Q Sure.

Mr. Lelling. I don’t think he can give you further detail.

The day after this October 23 interview, in which Brady claimed to have randomly discovered the 3-year old informant report that led to the reinterview that led to the FD-1023 Republicans want to build impeachment on by searching on Hunter Biden and Burisma — or maybe it was Zlochevsky and Burisma, Grassley released his letter with a slightly different story than the one Brady offered about how Brady came to learn about the 3-year old informant report.

While Grassley, whose understanding tends to rely on disgruntled right wing gossip, is often wrong in his claims about causality and here only speculates that Zlochevsky came up, Grassley nevertheless revealed a US Kleptocapture investigation into Zlochevsky, one that was opened in 2016 and shut down in December 2019.

Although investigative activity was scuttled by the FBI in 2020, the origins of additional activity relate back to years earlier. For example, in December 2019, the FBI Washington Field Office closed a “205B” Kleptocracy case, 205B-[redacted] Serial 7, into Mykola Zlochevsky, owner of Burisma, which was opened in January 2016 by a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act FBI squad based out of the FBI’s Washington Field Office. This Foreign Corrupt Practices Act squad included agents from FBI HQ. In February 2020, a meeting took place at the FBI Pittsburgh Field Office with FBI HQ elements. That meeting involved discussion about investigative matters relating to the Hunter Biden investigation and related inquiries, which most likely would’ve included the case against Zlochevsky. Then, in March 2020 and at the request of the Justice Department, a “Guardian” Assessment was opened out of the Pittsburgh Field Office to analyze information provided by Rudy Giuliani.

During the course of that assessment, Justice Department and FBI officials located an FD-1023 from March 1, 2017, relating to the “205B” Kleptocracy investigation of Zlochevsky. That FD1023 included a reference to Hunter Biden being on the board of Burisma, which the handling agent deemed at the time non-relevant information to the ongoing criminal financial case. And when that FD-1023 was discovered, Justice Department and FBI officials asked the handler for the Confidential Human Source (CHS) to re-interview that CHS. According to reports, there was “a fight for a month” to get the handler to re-interview the CHS. [my emphasis]

Lev Parnas claimed that Zlochevsky was offering to trade dirt on Biden for favor with DOJ in May 2019, and according to Grassley, in December 2019 — the same month Rudy picked up dirt in Ukraine — DOJ shut down a 3-year old investigation into Zlochevsky, one that was opened during the Obama Administration when Hunter was on the board of Burisma. The source of the tip on the informant is, at least if we can believe Grassley, the investigation on Zlochevsky that got shut down the same month as Rudy picked up his dirt.

Given Brady’s refusal to answer whether he knew about the money laundering investigation, it’s likely he knew about that investigation and so may even have been doing this math as he sat there being quizzed, discreetly, by Democratic staffers. The source of the informant tip his “vetting” operation pushed to the Hunter Biden investigation — the one on which Republicans want to build impeachment — may be the source of Zlochevsky’s interest in trading dirt on Joe Biden in exchange for favor with DOJ.

According to Brady, Rudy didn’t tell him about the earlier events, and his “vetting” team never bothered to look in impeachment materials to find that out.

The possible quid pro quo behind Republicans’ favorite impeachment evidence

To be sure, there are still major parts of this evolving outline that cannot be substantiated. The letter Parnas sent to James Comer doesn’t include the detail from Politico about currying favor (though it does include notice in June 2019 of a laptop on offer).

SDNY found Parnas to be unreliable about these topics (though who knows if that was based on “corrections” from Scott Brady?). As noted, Democratic staffers conflated Dmitry Firtash’s efforts to reach out to Bill Barr with this reported effort to curry favor. In a November 2019 interview not mentioned by Democratic staffers, Pruss denied any role in all this.

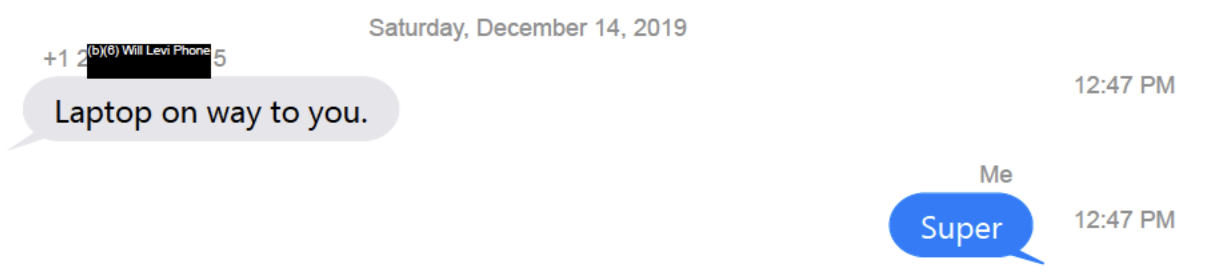

But the claimed timeline is this. In May 2019, Vitaly Pruss did an interview of Zlochevsky, seeking dirt on Biden for Rudy. After Rudy erupted at a June meeting because Zlochevsky had none, Pruss floated some, possibly a laptop, if Rudy could curry favor with DOJ. In August, a whistleblower revealed that Trump asked Zelenskyy to help Rudy and Barr with this project, kicking off impeachment in September. In October 2019, Parnas and Rudy prepared to make that trade in Vienna, dirt for DOJ assistance, only to be thwarted by Parnas’ arrest. According to the FBI, six days later (but according John Paul Mac Isaac, the day before the Parnas arrest), JPMI’s father first reached out to DOJ offering a Hunter Biden laptop. In December, a bunch of things happened: Rudy met with Andrii Derkach; the government took possession — then got a warrant for — the laptop, followed the next day by Barr’s aides informing him they were sending a laptop; the House voted to impeach Trump, and if we can believe Grassley — on an uncertain date — DOJ closed the Kleptocracy investigation into Zlochevsky they had opened during the Obama Administration. Sometime in this period (as I noted in this thread, the informant’s handler remarkably failed to record the date of this exchange, but it almost certainly happened after the Zelenskyy call was revealed and probably happened during impeachment), the informant’s tie to Zlochevsky, Oleksandr Ostapenko, interrupted a meeting about other matters to call Zlochevsky which is when Zlochevsky alluded to funds hidden so well it would take 10 years for investigators to find them.

Then, just days into January, DuCharme tasked Brady with ingesting dirt from Rudy, and after consultation with DuCharme, Brady decided he’d attend the interview with Rudy “so we get a sense of what’s coming out of it.” In that interview, Rudy didn’t tell DOJ about the interview that Parnas claims he solicited with Zlochevsky. He didn’t tell Brady he had first heard of laptops on order in June 2019. Nor did he tell DOJ, months later, when he obtained a hard drive from the laptop from John Paul Mac Isaac, still several weeks before Brady submitted a report to Richard Donoghue on the dirt Rudy was dealing.

If you corroborate Parnas’ claims about what happened in May and June 2019, then Zlochevsky’s later comments — possibly made after a DOJ investigation into him got shut down — look like the payoff of a quid pro quo. Remarkably, Brady never factored that possibility into his vetting project because he didn’t actually vet the most important details.

Scott Brady will undoubtedly make a more credible witness than Gal Luft if and when Republicans move to impeach Joe Biden. After all, he’ll be able to show up without getting arrested!

But this deposition made several things clear. First, his task, which public explanations have always claimed was about vetting dirt from Rudy Giuliani, did very little vetting. And, more importantly, if Lev Parnas’ claims to have solicited an interview on behalf of Rudy are corroborated, then Rudy would have deliberately hidden one of the most consequential details of his efforts to solicit the dirt that the DOJ, just weeks after closing an investigation into Mykola Zlochevsky, would set up a special channel to sheep dip into the investigation into President Trump’s opponent’s son.

It turns out that the most senior, credible witness in Republicans’ planned impeachment against Joe Biden actually has more to offer about Trump’s corruption than Biden’s.